Draft Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clay Madsen Recreation Center 1600 Gattis School Road Afterschool/Preschool Programs

2 Register online at www.RoundRockRecreation.com ROUND ROCK PARKS AND RECREATION DEPARTMENTS Parks and Recreation Office 301 W. Bagdad, Suite 250 Round Rock, TX 78664 Table of Contents Phone: 512-218-5540 Office Hours 50+ Adults (Baca Center) ..................................................................6 Mon.–Fri.: 8:00am–5:00pm Adaptive & Inclusive Recreation (AIR) ..................................... 17 Clay Madsen Recreation Center 1600 Gattis School Road Afterschool/Preschool Programs ................................................ 24 Round Rock, TX 78664 Aquatics & Swim Lessons ............................................................. 28 Phone: 512-218-3220 Administration Office Hours Arts & Enrichment .......................................................................... 36 Mon.–Fri.: 8:00am–6:00pm Camps .................................................................................................. 38 Allen R. Baca Center 301 W. Bagdad, Building 2 Fitness & Wellness .......................................................................... 42 Round Rock, TX 78664 Outdoor Recreation/Adventure ................................................... 45 Phone 512-218-5499 Administration Office Hours Special Events ................................................................................... 46 Mon.–Thurs.: 8:00am–6:00pm Fri.: 8:00am–4:00pm Sports ................................................................................................... 51 Register online at www.RoundRockRecreation.com Reasonable Accommodations -

Guide to Civic Tech and Data Ecosystem Mapping

Guide to Civic Tech & Data Ecosystem Mapping JUNE 2018 Olivia Arena Urban Institute Crystal Li Living Cities Guide to Civic Tech & Data Ecosystem Mapping CONTENTS Introduction to Ecosystem Mapping 03 Key Questions to Ask before Getting Started 05 Decide What Data to Collect 07 Choose a Data-Collection 09 Methodology and Mapping Software Analyze Your Ecosystem Map 11 Appendix A – Ecosystem Mapping Tools Analysis 14 For more information on the Civic Tech & Data Collaborative visit livingcities.org/CTDC 1 Guide to Civic Tech & Data Ecosystem Mapping About the National Partners Living Cities harnesses the collective power of 18 of the world’s largest foundations and financial institutions to develop and scale new approaches for creating opportunities for low-income people, particularly people of color, and improving the cities where they live. Its investments, applied research, networks, and convenings catalyze fresh thinking and combine support for innovative, local approaches with real-time sharing of learning to accelerate adoption in more places. Additional information can be found at www.livingcities.org. The nonprofit Urban Institute is a leading research organization dedicated to developing evidence-based insights that improve people’s lives and strengthen communities. For 50 years, Urban has been the trusted source for rigorous analysis of complex social and economic issues; strategic advice to policy- makers, philanthropists, and practitioners; and new, promising ideas that expand opportunities for all. Our work inspires efective decisions that advance fairness and enhance the well-being of people and places. Coordinated by the Urban Institute, the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP) consists of independent organizations in 32 cities that share mission to help community stakeholders use neighborhood data for better decisionmaking, with a focus on assisting organizations and residents in low- income communities. -

Convergent Evolution of 'Creepers' in the Hawaiian Honeycreeper

ARTICLE IN PRESS Biol. Lett. 1. INTRODUCTION doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0589 Adaptive radiation is a fascinating evolutionary pro- 1 cess that has generated much biodiversity. Although 65 2 Evolutionary biology several mechanisms may be responsible for such 66 3 diversification, the ‘ecological theory’ holds that it is 67 4 the outcome of divergent natural selection between 68 5 Convergent evolution of environments (Schluter 2000). Whether adaptive 69 6 radiations result chiefly from such ecological speciation, 70 7 ‘creepers’ in the Hawaiian however, remains unclear (Schluter 2001). Convergent 71 8 evolution is often considered powerful evidence for the 72 9 honeycreeper radiation role of adaptive forces in the speciation process 73 (Futuyma 1998), and thus documenting cases where it 10 Dawn M. Reding1,2,*, Jeffrey T. Foster1,3, 74 has occurred is important in understanding the link 11 Helen F. James4, H. Douglas Pratt5 75 12 between natural selection and adaptive radiation. 76 and Robert C. Fleischer1 13 The more than 50 species of Hawaiian honeycree- 77 1 14 Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, National pers (subfamily Drepanidinae) are a spectacular 78 Zoological Park and National Museum of Natural History, 15 Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20008, USA example of adaptive radiation and an interesting 79 16 2Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, system to test for convergence, which has been 80 17 HI 96822, USA suspected among the nuthatch-like ‘creeper’ eco- 81 3Center for Microbial Genetics & Genomics, -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Keauhou Bird Conservation Center

KEAUHOU BIRD CONSERVATION CENTER Discovery Forest Restoration Project PO Box 2037 Kamuela, HI 96743 Tel +1 808 776 9900 Fax +1 808 776 9901 Responsible Forester: Nicholas Koch [email protected] +1 808 319 2372 (direct) Table of Contents 1. CLIENT AND PROPERTY INFORMATION .................................................................... 4 1.1. Client ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Consultant ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 5 3. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1. Site description ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Parcel and location .................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.2. Site History ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. Plant ecosystems ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.2.1. Hydrology ................................................................................................................................ -

Hawaiʻi's Big Five

Hawaiʻi’s Big Five (Plus 2) “By 1941, every time a native Hawaiian switched on his lights, turned on the gas or rode on a street car, he paid a tiny tribute into Big Five coffers.” (Alexander MacDonald, 1944) The story of Hawaii’s largest companies dominates Hawaiʻi’s economic history. Since the early/mid- 1800s, until relatively recently, five major companies emerged and dominated the Island’s economic framework. Their common trait: they were focused on agriculture - sugar. They became known as the Big Five: C. Brewer (1826;) Theo H. Davies (1845;) Amfac - starting as Hackfeld & Company (1849;) Castle & Cooke (1851) and Alexander & Baldwin (1870.) C. Brewer & Co. Amfac Founded: October 1826; Capt. James Hunnewell Founded: 1849; Heinrich Hackfeld and Johann (American Sea Captain, Merchant; Charles Carl Pflueger (German Merchants) Brewer was American Merchant) Incorporated: 1897 (H Hackfeld & Co;) American Incorporated: February 7, 1883 Factors Ltd, 1918 Theo H. Davies & Co. Castle & Cooke Founded: 1845; James and John Starkey, and Founded: 1851; Samuel Northrup Castle and Robert C. Janion (English Merchants; Theophilus Amos Starr Cooke (American Mission Secular Harris Davies was Welch Merchant) Agents) Incorporated: January 1894 Incorporated: 1894 Alexander & Baldwin Founded: 1870; Samuel Thomas Alexander & Henry Perrine Baldwin (American, Sons of Missionaries) Incorporated: 1900 © 2017 Ho‘okuleana LLC The Making of the Big Five Some suggest they were started by the missionaries. Actually, only Castle & Cooke has direct ties to the mission. However, Castle ran the ‘depository’ and Cooke was a teacher, neither were missionary ministers. Alexander & Baldwin were sons of missionaries, but not a formal part of the mission. -

Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan

United Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Research Article Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan Siraj I1, Rahman SU1, Ahsan Naveed1* Anjum Fr1, Hassan S2, Zahid Ali Tahir3 1Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 2Institute of Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan 3DiagnosticLaboraoty, Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan Volume 1 Issue 1- 2018 1. Abstract Received Date: 15 July 2018 1.1. Introduction Accepted Date: 31 Aug 2018 The study was aimed to check the prevalence of this zoonotic bacterium which is a great risk Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 towards human population in district Faisalabad at Pakistan. 1.2. Methodology 2. Key words Chlamydia Psittaci; Psittacosis; In present study, a total number of 259 samples including fecal swabs (187) and blood samples Prevalence; Zoonosis (72) from different aviculture of 259 birds such as chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots, Australian parrots, and peacock were collected from different regions of Faisalabad, Pakistan. After process- ing the samples were inoculated in the yolk sac of embryonated chicken eggs for the cultivation ofChlamydia psittaci(C. psittaci)and later identified through Modified Gimenez staining and later CFT was performed for the determination of antibodies titer against C. psittaci. 1.3. Results The results of egg inoculation and modified Gimenez staining showed 9.75%, 29.62%, 10%, 36%, 44.64% and 39.28% prevalence in the fecal samples of chickens, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pi- geons and Australian parrots respectively. Accordingly, the results of CFT showed 15.38%, 25%, 46.42%, 36.36% and 25% in chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots and peacock respectively. -

The Relationships of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers (Drepaninini) As Indicated by Dna-Dna Hybridization

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS (DREPANININI) AS INDICATED BY DNA-DNA HYBRIDIZATION CH^RrES G. SIBLEY AND Jo• E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--Twenty-twospecies of Hawaiian honeycreepers(Fringillidae: Carduelinae: Drepaninini) are known. Their relationshipsto other groups of passefineswere examined by comparing the single-copyDNA sequencesof the Apapane (Himationesanguinea) with those of 5 speciesof carduelinefinches, 1 speciesof Fringilla, 15 speciesof New World nine- primaried oscines(Cardinalini, Emberizini, Thraupini, Parulini, Icterini), and members of 6 other families of oscines(Turdidae, Monarchidae, Dicaeidae, Sylviidae, Vireonidae, Cor- vidae). The DNA-DNA hybridization data support other evidence indicating that the Hawaiian honeycreepersshared a more recent common ancestorwith the cardue!ine finches than with any of the other groupsstudied and indicate that this divergenceoccurred in the mid-Miocene, 15-20 million yr ago. The colonizationof the Hawaiian Islandsby the ancestralspecies that radiated to produce the Hawaiian honeycreeperscould have occurredat any time between 20 and 5 million yr ago. Becausethe honeycreeperscaptured so many ecologicalniches, however, it seemslikely that their ancestor was the first passefine to become established in the islands and that it arrived there at the time of, or soon after, its separationfrom the carduelinelineage. If so, this colonist arrived before the present islands from Hawaii to French Frigate Shoal were formed by the volcanic"hot-spot" now under the island of Hawaii. Therefore,the ancestral drepaninine may have colonizedone or more of the older Hawaiian Islandsand/or Emperor Seamounts,which also were formed over the "hot-spot" and which reachedtheir present positions as the result of tectonic crustal movement. -

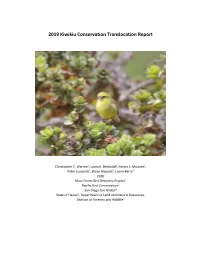

2019 Kiwikiu Conservation Translocation Report

2019 Kiwikiu Conservation Translocation Report Christopher C. Warren1, Laura K. Berthold1, Hanna L. Mounce1, Peter Luscomb2, Bryce Masuda3, Lainie Berry4 2020 Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project1 Pacific Bird Conservation2 San Diego Zoo Global3 State of Hawaiʻi, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife4 Suggested citation – Warren, C.C., L.K. Berthold, H.L. Mounce, P. Luscomb, B. Masuda. L. Berry. 2020. Kiwikiu Translocation Report 2019. Internal Report. Pages 1–101. Cover photo by Bret Mossman. Translocated female, WILD11, in Kahikinui Hawaiian Homelands. Photo credits – Photographs were supplied by Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP) staff, members of the press, and volunteers. Photographer credit is given for those not taken by MFBRP staff. The 2019 kiwikiu translocation was a joint operation conducted by member organizations of the Maui Forest Bird Working Group. Organizations that conducted the translocation included American Bird Conservancy, Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, National Park Service, Pacific Bird Conservation, San Diego Zoo Global, State of Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources – Division of Forestry and Wildlife, The Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. In addition to representatives of these organizations, six community volunteers aided in these efforts. This does not include the dozens of volunteers and other organizations involved in planning for the translocation and preparing the release site through restoration and other activities. These efforts were greatly supported by the skilled pilots at Windward Aviation. i Table of Contents 1. Summary of 2019 Reintroduction ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background of the Reintroduction ....................................................................................................... 1 2.1. -

Quantitative Genetic Variation in Declining Plant Populations

Quantitative genetic variation in declining plant populations Ellmer, Maarten 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ellmer, M. (2009). Quantitative genetic variation in declining plant populations. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 QUANTITATIVE GENETIC VARIATION IN DECLINING PLANT POPULATIONS Quantitative genetic variation in declining plant populations Maarten Ellmer ACADEMIC DISSERTATION For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Ecology and Systematics, to be publicly defended on October 2nd at 10.00 a.m. in Blå Hallen at the Department of Ecology, Ecology Building, Sölvegatan 37, Lund, by permission of the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Lund. -

Apapane (Himatione Sanguinea)

The Birds of North America, No. 296, 1997 STEVEN G. FANCY AND C. JOHN RALPH 'Apapane Himatione sanguinea he 'Apapane is the most abundant species of Hawaiian honeycreeper and is perhaps best known for its wide- ranging flights in search of localized blooms of ō'hi'a (Metrosideros polymorpha) flowers, its primary food source. 'Apapane are common in mesic and wet forests above 1,000 m elevation on the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, and Kaua'i; locally common at higher elevations on O'ahu; and rare or absent on Lāna'i and Moloka'i. density may exceed 3,000 birds/km2 The 'Apapane and the 'I'iwi (Vestiaria at times of 'ōhi'a flowering, among coccinea) are the only two species of Hawaiian the highest for a noncolonial honeycreeper in which the same subspecies species. Birds in breeding condition occurs on more than one island, although may be found in any month of the historically this is also true of the now very rare year, but peak breeding occurs 'Ō'ū (Psittirostra psittacea). The highest densities February through June. Pairs of 'Apapane are found in forests dominated by remain together during the breeding 'ōhi'a and above the distribution of mosquitoes, season and defend a small area which transmit avian malaria and avian pox to around the nest, but most 'Apapane native birds. The widespread movements of the 'Apapane in response to the seasonal and patchy distribution of ' ōhi'a The flowering have important implications for disease Birds of transmission, since the North 'Apapane is a primary carrier of avian malaria and America avian pox in Hawai'i. -

THE STATUS of the MAUNA KEA SILVERSWORD Gerald D. Carr And

34 THE STATUS OF THE MAUNA KEA SILVERSWORD Gerald D. Carr and Alain Meyrat Department of Botany University of Hawaii 3190 Maile Way Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 The Mauna Kea silversword was first brought to the attention of the scientific community through the efforts of Scottish botanist James M~crae. Macrae ascended Mauna Kea from Laupahoehoe in 1825 and at a point near the summit, after walking three miles over sandy pulverized lava, noted, "The last mile was destitute of vegetation except one plant of the Syginesia tribe, in growth much like a Yucca, with sharp pointed silver cou1oured leaves and green upright spike of three or four feet producing pendulous branches with br9wn flowers, truly superb, and almost worth the journey of coming here to s~e it on purpose" (Wilson 1922, p. 54). Specimens of t;hese 'truly superb' plants reached De Candolle and in 1836 were christened Argyroxiphium sandwicense DC. Early in 1834, David Douglas ascended Mauna Kea and observed the same species, specimens of which reached W. J. Hooker and were initially given the name Argyrophyton douglasii Hook. (1837a.), but Hooker very soon a.ccepted De Candolle's earlier name for the taxon (Hooker 1837b). ,The species was again collected on Mauna Kea by Charles Pickering in 1841 as part of the U. S. South Pacific Exploring Expedition (cf. Pickering 1876, Keck 1936). Pickering also collected material he presumed to belong to the Same taxon on Haleakala, Maui, but this was considered distinct by Asa Gray and was named Argyroxiphium macrocephalum (cf. Gray 1852, Pickering 1876). Both Pickering and Douglas observed Argyroxiphium on Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, Hawai'i and considered them to be the same taxon (Pickering 1876, Wilson 1922).