Audit Committees in Switzerland Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Annual General Meeting Invitation, Proxy Statement and Annual Report

2017 Annual General Meeting Invitation, Proxy Statement and Annual Report TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS WE’VE COME A LONG WAY… So, we have come a long way. Which gives us an opportunity to put this company - now in its 35th year - When we meet people from outside Logitech, we often into a broader perspective as we look ahead. For both hear, “Wow, you really had a terrific year!”, or “What a of us, it’s an anniversary of sorts this year. Guerrino turnaround this past year or two!”. celebrates 20 years at Logitech in a few months and Bracken celebrates his first five. Let’s step back and think The truth is we started down this road five years ago. about the world in which we now play. After all, you’re That was Fiscal Year 2013, when retail sales in constant reading this because you’re interested in what’s ahead. currency fell -7% year on year. TOOLS ENHANCE OUR LIVES We made changes to our strategy, our culture and our team. And since then we’ve systematically and Let’s step way back to the dawn of humanity; even before Letter to Shareholders passionately worked toward our goal to become a design history was recorded. Our earliest tools were knives, company. A design company is not one focused on spears, the wheel, jugs and more. They enabled us to do fashion or beautiful products (although our products are things we couldn’t do on our own and became stepping beautiful). It’s a company that puts the consumer at the stones for new advances. -

Swiss Leader Index Price Index Index

BLUE-CHIP INDICES 1 SWISS LEADER INDEX PRICE INDEX INDEX Index description Key facts The SLI Swiss Leader Index includes the 30 most liquid stocks traded in the » "In order to achieve the stated index objective SIX Swiss Ex-change defines Swiss equity market, the developments of which are reflected by the SPI® the general principles that govern the index methodology. SIX Swiss Family. Consequently, the index weighting of a given issue is limited by Exchange publishes the index objective and rules for all indices. means of a 9/4,5 capping model. In other words, the weighting of each of the four companies with the largest market capitalisation is capped at a » Representative: the development of the market is represented by the maximum of 9 %. The weightings of all lower-ranked companies are if index necessary capped at 4.5 %. This limitation will be calculated by applying a » Tradable: the index components are tradable in terms of company size capping factor, which as a general rule will remain constant for a three- and market month period. The SLI offers a number of advantages: for investors, the capping feature improves their stock- and sector specific diversification and, » Replicable: the development of the index can be replicated in practise with because the new index fulfils Swiss, EU and US regulatory requirements, a portfolio new markets can be opened with products based on the SLI. That, in turn, generates liquidity for the stocks included in the basket. » Stable: high index continuity » Rules-based: index changes and calculations -

Results Zrating Study 2019 on Corporate Governance

Zurich, 12 September 2019 Media release Results zRating Study 2019 on Corporate Governance Zürich, 12 September 2019 – Sunrise once again scores highest in this year’s corporate governance ranking followed by Swisscom (81 points) and Lonza (78 points). Due to amendments to the Articles of Association, also induced by activist shareholders, and changes in practices, companies have improved their corporate governance. For the eleventh time since 2009, the zRating Study on corporate governance in Swiss public companies has been published. zRating summarizes the situation regarding shareholders' rights in a company and draws attention to possible conflicts between shareholders and managers. zRating evaluates corporate governance holistically based on 62 criteria from the categories «Shareholders and Capital Structure», «Shareholders' Rights», «Composition Board of Directors/Management and Information Policy», and «Compensation and participation models». The criteria are weighted in a scoring model and evaluated with points. The total maximum of points is 100. 174 listed Swiss companies are analyzed based on Annual Reports 2018 and decisions at General Meetings 2019. Further improvements through amendments to the Articles of Association Once again Sunrise takes first place with 86 points. They had already gained a large lead thanks to amendments to the Articles of Association at the annual general meetings (AGM) in 2017 and 2018, and in 2019 Sunrise was also able to score in the new criteria. Second place went to Swisscom with 81 points and third place to Lonza with 78 points. This year, the boards of directors of Mobilezone, Peach Property and Starrag in particular proposed amendments to the Articles of Association that strengthened shareholders' participation rights. -

Liste Der Unternehmen Im SMI Expanded Und Ihre Derzeitige Kapitalschwelle Für Das Traktandierungsrecht an Der Generalversammlung

Liste der Unternehmen im SMI Expanded und ihre derzeitige Kapitalschwelle für das Traktandierungsrecht an der Generalversammlung Schwellenwert Unternehmen Sitz Index Nennwertschwelle Anmerkungen in % des Kapitals ABB Zürich (ZH) SMI 48'000 0.02% Alcon Fribourg (FR) SMI 1'000'000 5.00% Credit Suisse Group Zürich (ZH) SMI 40'000 0.04% Geberit Rapperswil-Jona (SG) SMI 4'000 0.11% Givaudan Vernier (GE) SMI 1'000'000 1.08% LafargeHolcim Jona (SG) SMI 1'000'000 0.08% Lonza Basel (BS) SMI 100'000 0.13% Nestlé Vevey/Cham (VD/ZG) SMI - 0.15% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Novartis Basel (BS) SMI 1'000'000 0.08% Partners Group Baar (ZG) SMI - 10.00% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Richemont Bellevue (GE) SMI 1'000'000 0.19% Roche Basel (BS) SMI 1'000'000 0.63% SGS Genève (GE) SMI 50'000 0.66% Sika Baar (ZG) SMI 10'000 0.71% Swatch Group Neuchâtel (NE) SMI 1'000'000 1.54% Swiss Life Zürich (ZH) SMI - 0.25% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Swiss Re Zürich (ZH) SMI 100'000 0.31% Swisscom Ittigen (BE) SMI 40'000 0.08% UBS Zürich/Basel (ZH/BS) SMI 62'500 0.02% Zurich Insurance Zürich (ZH) SMI 10'000 0.07% Adecco Zürich (ZH) SMIM 100'000 0.61% AMS Unterpremstätten (Autriche) SMIM NR NR Österreichisches Unternehmen Bâloise Basel (BS) SMIM 100'000 2.05% Barry Callebaut Zürich (ZH) SMIM - 0.25% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals BB Biotech Schaffhausen (SH) SMIM 1'000'000 9.03% Cembra Money Bank Zürich (ZH) SMIM 1'000'000 3.33% Clariant Muttenz (BL) SMIM 1'000'000 0.08% Dufry Basel (BS) SMIM 1'000'000 0.25% Ems-Chemie Domat / Ems (GR) SMIM - 10.00% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Flughafen Zürich Kloten (ZH) SMIM 1'000'000 0.33% Galenica Berne (BE) SMIM - 5.00% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Georg Fischer Schaffhausen (SH) SMIM - 0.30% Schwellenwert in % des Kapitals Helvetia St. -

Is Integrated Reporting Gaining Interest in Switzerland?

4 INTEGRATED REPORTING Elfte Ausgabe Is Integrated Reporting gaining interest in Switzerland? Sustainability reporting is wide-spreading among Swiss companies with number of reporters increasing year after year. And now also Integrated Reporting is gaining traction. By Roger Müller, Mark Vesser and Chiara Rinaldi At its sixth release, the annual review of the status of sustainabil- Decline in the application ity reporting in Switzerland (EY, Targeting transparency, 2017) of the GRI Reporting Framework shows that sustainability reporting in Switzerland continues to ROGER MÜLLER spread among companies of all industries. There is a decrease in the application of the GRI Reporting Frame- is Partner and Zurich office work both for the companies in the SMI Expanded and for the leader at EY Switzerland. He is 110 largest Swiss companies. The share of companies in the SMI heading the Financial Accoun- Increase in sustainability reporting ting Advisory Services including Expanded applying the GRI Reporting Framework decreased the Climate Change and Susta- Both the share of companies in the SMI Expanded and of the 100 from 79% for the reporting year 2015 to 73% for 2016. For the 110 inability Services. He has broad largest companies, five largest banks and five largest insurers largest companies, the number decreased from 78% to 64% in the experience in all the main topics on the CFO’s agenda. He leads publishing a sustainability report has increased for the reporting same period. In both cases, this is mainly due to new reporters complex engagements related to year 2016 compared to 2015. For the companies in the SMI Ex- not applying GRI. -

Swiss Market Index (SMI®) Family

Swiss Market Index (SMI®) Family The SMI® Family: SMI®, SMIM® and SMI Expanded® The SMI Family, which is the best-known index family of SIX Swiss Exchange, comprises the 50 largest and most liquid stocks in the Swiss equity market. The blue-chip index SMI is the most significant equity index in Switzerland. It comprises 20 of the largest stocks from the SPI® universe. The SMIM comprises the next group of the 30 largest and most liquid mid-cap stocks. All SMI and SMIM stocks are consolidated in the SMI Expanded. The SMI Expanded covers more than 90 % of the capitalisation of the Swiss equity market. SMI® Family data SMI SMIM SMI Expanded Price Total Return (TR) Price Total Return (TR) Price Total Return (TR) Symbol SMI SMIC SMIM SMIMC SMIEXP SMIEXC Security no. 998089 22213 1939983 1939982 1939986 1939985 ISIN CH0009980894 CH0000222130 CH0019399838 CH0019399820 CH0019399861 CH0019399853 Reuters RIC .SSMI .SMIC .SMIM .SMIMC .SMIEXP .SMIEXC Bloomberg ticker SMI SMIC SMIM SMIMC SMIEXP SMIEXC Index structure SIX Swiss Exchange SPI® Family SMI® Family SLI® SXI® Family 0 SLI Swiss * Sector ** SPI® Large SMI® Sector SXI Switzerland Leader SXI SXI Sustainability 25® 20 Life Sciences® SMI Index® Real Estate® 30 Expanded® SMIM® 50 SPI® Mid SPI® SPI EXTRA® 100 Swiss SPI ex SLI® All Share Index SPI® Small ~230 Investment Index ~250 Shares < 20% FF ~270 * Sector Real Estate: SXI Real Estate®, SXI Real Estate® Shares, SXI Real Estate® Funds, SXI Swiss Real Estate®, SXI Swiss Real Estate® Shares, SXI Swiss Real Estate® Funds ** Sector Life Sciences: SXI Life Sciences®, SXI-Bio+Medtech® Risk and return profile Returns Risk (Volatility) Sharpe Ratio SMI TR SMIM TR SMI Exp. -

Besitzverhältnisse an Börsenkotierten Schweizerischen Unternehmungen

Strukturberichterstattung Nr. 59 Heinz Zimmermann Yvonne Seiler Zimmermann Besitzverhältnisse an börsenkotierten schweizerischen Unternehmungen Eine Analyse des «SMI expanded» Aktienuniversums Studie im Auftrag des Staatssekretariats für Wirtschaft SECO Strukturberichterstattung Nr. 59 Heinz Zimmermann Yvonne Seiler Zimmermann Besitzverhältnisse an börsenkotierten schweizerischen Unternehmungen Eine Analyse des «SMI expanded» Aktienuniversums Studie im Auftrag des Bern, 2019 Staatssekretariats für Wirtschaft SECO 2 Die vorliegende Studie ersetzt eine frühere Version vom 13. Februar 2019 mit dem gleichen Titel. Nebst einer Datenüberprüfung und -bereinigung wurde die Klassifikation der Aktionäre resp. Aktionärsgruppen aufgrund der verwendeten SIX-Meldungen, welche mit einem Ermes- sensspielraum verbunden sind, überprüft und teilweise geändert. Diese Fälle sind in der vorlie- genden Studie ausführlicher dokumentiert. Dadurch haben sich zwar die Hauptaussagen der Studie nicht verändert, wohl aber die ausgewiesenen prozentualen Anteile bei den Anteilen der Länder/ Regionen sowie Investorenkategorien. Heinz Zimmermann und Yvonne Seiler Zimmermann – Besitzverhältnisse an kotierten schweizerischen Unternehmen 3 Executive Summary In der Öffentlichkeit besteht ein verbreitetes Unbehagen gegenüber der Beteiligung ausländi- scher Investoren an schweizerischen Unternehmungen. Genaue und vollständige Informationen über den tatsächlichen Umfang und die Struktur von Beteiligungen werden jedoch nicht erho- ben und sind daher nicht verfügbar. Mit der Einführung -

Open End Turbo Call Warrant Linked to SMI® Issued by UBS AG, Zurich

Open End Turbo Call Warrant Linked to SMI® Issued by UBS AG, Zurich Cash settled SVSP/EUSIPA Product Type: Knock-Out Warrants (2200) Valor: 46256143 / SIX Symbol: OSMIXU Final Termsheet This Product does not represent a participation in any of the collective investment schemes pursuant to Art. 7 ff of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes (CISA) and thus does not require an authorisation of the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). Therefore, Investors in this Product are not eligible for the specific investor protection under the CISA. Moreover, Investors in this Product bear the issuer risk. This document (Final Termsheet) constitutes the Simplified Prospectus for the Product described herein; it can be obtained free of charge from UBS AG, P.O. Box, CH-8098 Zurich (Switzerland), via telephone (+41-(0)44-239 47 03), fax (+41-(0)44-239 69 14) or via e-mail ([email protected]). The relevant version of this document is stated in English; any translations are for convenience only. For further information please refer to paragraph «Product Documentation» under section 4 of this document. 1. Description of the Product Information on Underlying Underlying(s) Reference Level Initial Strike / Knock-Out Barrier Conversion Ratio SMI® 9,333.57 8,518.20 500:1 Bloomberg: SMI / Valor: 998089 Product Details Security Numbers Valor: 46256143 / ISIN: CH0462561439 SIX Symbol OSMIXU Issue Size Up to 1,500,000 units (with reopening clause) Issue Price CHF 1.68 (unit quotation) Redemption Currency CHF Initial Leverage 11.31 Type of Product Down and Out Call Warrant Dates Launch Date 22 February 2019 Fixing Date 22 February 2019 First SIX Trading Date (anticipated) 25 February 2019 Initial Payment Date (Issue Date) 01 March 2019 Expiration Date ("Expiry") Open End Valuation Date means the day when either the Investor’s Exercise Right or the Issuer’s Call Right becomes effective. -

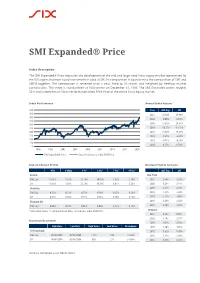

SMI Expanded® Price the SMI Expanded® Price Measures the Development Of

SMI Expanded® Price Index Description The SMI Expanded® Price measures the development of the mid and large sized Swiss equity market represented by the 50 largest and most liquid instruments traded at SIX. Its composition is equivalent to the composition of SMI and SMIM together. The composition is reviewed once a year, fixed to 50 shares and weighted by freefloat market capitalisation. The index is standardised at 1000 points on December 31, 1999. The SMI Expanded covers roughly 92% and its benchmark Swiss Performance Index SPI® Price of the entire Swiss equity market. Index Performance Annual Index Return¹ 500 Year SMI Exp. SPI 450 2021 25.66% 25.98% 400 2020 -0.04% 0.61% 350 2019 27.02% 26.51% 300 250 2018 -10.77% -11.43% 200 2017 16.03% 16.37% 150 2016 -5.49% -4.67% 100 2015 -0.71% -0.25% 50 2014 9.55% 9.73% 0 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 SMI Expanded® Price Swiss Performance Index SPI® Price Risk and Return Profile Dividend Yield & Turnover YTD 3 Mths 1 Yr¹ 3 Yrs¹ 7 Yrs¹ 15 Yrs¹ SMI Exp. SPI Return Div. Yield SMI Exp. 16.45% 8.76% 22.16% 10.93% 5.83% 3.19% 2021 2.64% 2.58% SPI 16.65% 8.68% 22.59% 10.78% 6.01% 3.23% 2020 3.23% 3.19% Volatility 2019 3.14% 3.10% SMI Exp. 0.62% 0.51% 0.73% 0.59% 0.37% 0.28% 2018 3.27% 3.20% SPI 0.61% 0.50% 0.72% 0.58% 0.36% 0.28% 2017 3.15% 3.09% Tracking Err. -

SXI® Special Industry Indices

SXI® Special Industry Indices SXI LIFE SCIENCES® and SXI Bio+Medtech® The SXI Family consists of specially selected sector indi- of two indices: SXI LIFE SCIENCES® (Pharma, Medtech and ces. The sectors are selected according to two criteria: Biotech) and its more narrowly circumscribed sub-index, their international significance and the number of SIX SXI Bio+Medtech. These index instruments meet the listed companies that belong to them. The SXI indices growing desire of institutional investors to invest in these comprise primary listed companies and investment market segments, and they also increase the attractive- companies in case they have invested less than 50% of ness of SIX as a market for companies in these sectors. their assets in SXI shares. Another feature of the SXI To sum up, the SXI Fami ly offers Swiss and foreign com- indices is that the weighting of any individual security panies in the relevant sectors an attractive platform and is limited to 10%. The pur pose of this weight cap is to provides investors with a benchmark for the highly pros- increase diversification and relative importance of pering industry. smaller constitu ents. The SXI Family currently consists SXI® Family data Symbol Security no. ISIN Reuters RIC Bloomberg ticker SXI LIFE SCIENCES® Price SLIFEX 17810 1781076 CH0017810760 .SLIFEX SLIFEX Total Return SLIFE 1781073 CH0017810737 .SLIFE SLIFE SXI Bio+Medtech® Price SBIOMX 17811156 CH0017811156 .SBIOMX SBIOMX Total Return SBIOM 17810794 CH0017810794 .SBIOM SBIOM Equity index structure Number of Shares SPI® -

Put Warrant Linked to SMI® Issued by UBS AG, Zurich

Put Warrant Linked to SMI® Issued by UBS AG, Zurich SVSP/EUSIPA Product Type: Warrant (2100) Valor: 55504794 Final Termsheet This Product does not represent a participation in any of the collective investment schemes pursuant to Art. 7 ff of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes (CISA) and thus does not require an authorisation of the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). Therefore, Investors in this Product are not eligible for the specific investor protection under the CISA. Moreover, Investors in this Product bear the issuer risk. This document (Final Termsheet) constitutes the Simplified Prospectus for the Product described herein; it can be obtained free of charge from UBS AG, P.O. Box, CH-8098 Zurich (Switzerland), via telephone (+41-(0)44-239 47 03), fax (+41-(0)44-239 69 14) or via e-mail ([email protected]). The relevant version of this document is stated in English; any translations are for convenience only. For further information please refer to paragraph «Product Documentation» under section 4 of this document. 1. Description of the Product Information on Underlying Underlying / Company Reference Level Strike Conversion Ratio SMI® 9,842.56 8,600.00 100:1 Bloomberg: SMI / Valor: 998089 Product Details Security Numbers Valor: 55504794 / ISIN: CH0555047940 Issue Size up to 4,000,000 Warrants (with reopening clause) Redemption Currency CHF Issue Price CHF 3.10 (unit quotation) Type of Product Put Option Style European Exercise at Expiry Automatically Dates Launch Date 18 June 2020 Fixing -

Schindler Annual Report 2016 Group Review English

Always on the move. With enthusiasm. Group Review 2016 Urban landscapes shaped by dedicated people and leading technology Schindler is a global provider of leading mobility solutions. Each day, its elevators and escalators transport over one billion people to their destinations safely and efficiently – serving the most diverse needs. Its offering ranges from cost-effective solutions for low-rise residential buildings to sophisticated access and transport management concepts for skyscrapers. Through its strategic investments, Schindler is able to provide energy-efficient and user-friendly solutions to meet today’s mobility needs. In this way, it can move people and materials and connect vertical and horizontal transport systems, thus helping to shape urban landscapes – both now and in the future. Our products and services Passenger elevators Schindler has an elevator solution to meet every individual need in the market – from low-rise requirements with a focus on affordable basic transportation through to mid-rise applications for the residential and commercial market segments and finally to high-rise solutions for buildings of up to 500 meters. Freight elevators Our freight elevators can transport small or large volumes of light or heavy freight. Escalators and moving walks Schindler has escalators for all applications – from shopping malls, offices, hotels, and entertainment centers, to busy airports, subways, and railway stations. Our moving walks – whether inclined or horizontal – ensure efficient transportation in public areas. Modernization We offer a range of elevator and escalator modernization products. Services The next technician is always within reach worldwide, 24 hours a day. Growth strategy < yielding results Growth strategy yielding results Despite a challenging market environment, orders received, revenue, and operating profit reached record levels.