Molecular Phylogenetics of Mosses and Relatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1-1 Introduction

Glime, J. M. 2017. Introduction. Chapt. 1. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored 1-1-1 by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 25 April 2021 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 1-1 INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Thinking on a New Scale .................................................................................................................................... 1-1-2 Adaptations to Land ............................................................................................................................................ 1-1-3 Minimum Size..................................................................................................................................................... 1-1-5 Do Bryophytes Lack Diversity?.......................................................................................................................... 1-1-6 The "Moss".......................................................................................................................................................... 1-1-7 What's in a Name?............................................................................................................................................... 1-1-8 Phyla/Divisions............................................................................................................................................ 1-1-8 Role of Bryology................................................................................................................................................ -

Systema Naturae∗

Systema Naturae∗ c Alexey B. Shipunov v. 5.802 (June 29, 2008) 7 Regnum Monera [ Bacillus ] /Bacteria Subregnum Bacteria [ 6:8Bacillus ]1 Superphylum Posibacteria [ 6:2Bacillus ] stat.m. Phylum 1. Firmicutes [ 6Bacillus ]2 Classis 1(1). Thermotogae [ 5Thermotoga ] i.s. 2(2). Mollicutes [ 5Mycoplasma ] 3(3). Clostridia [ 5Clostridium ]3 4(4). Bacilli [ 5Bacillus ] 5(5). Symbiobacteres [ 5Symbiobacterium ] Phylum 2. Actinobacteria [ 6Actynomyces ] Classis 1(6). Actinobacteres [ 5Actinomyces ] Phylum 3. Hadobacteria [ 6Deinococcus ] sed.m. Classis 1(7). Hadobacteres [ 5Deinococcus ]4 Superphylum Negibacteria [ 6:2Rhodospirillum ] stat.m. Phylum 4. Chlorobacteria [ 6Chloroflexus ]5 Classis 1(8). Ktedonobacteres [ 5Ktedonobacter ] sed.m. 2(9). Thermomicrobia [ 5Thermomicrobium ] 3(10). Chloroflexi [ 5Chloroflexus ] ∗Only recent taxa. Viruses are not included. Abbreviations and signs: sed.m. (sedis mutabilis); stat.m. (status mutabilis): s., aut i. (superior, aut interior); i.s. (incertae sedis); sed.p. (sedis possibilis); s.str. (sensu stricto); s.l. (sensu lato); incl. (inclusum); excl. (exclusum); \quotes" for environmental groups; * (asterisk) for paraphyletic taxa; / (slash) at margins for major clades (\domains"). 1Incl. \Nanobacteria" i.s. et dubitativa, \OP11 group" i.s. 2Incl. \TM7" i.s., \OP9", \OP10". 3Incl. Dictyoglomi sed.m., Fusobacteria, Thermolithobacteria. 4= Deinococcus{Thermus. 5Incl. Thermobaculum i.s. 1 4(11). Dehalococcoidetes [ 5Dehalococcoides ] 5(12). Anaerolineae [ 5Anaerolinea ]6 Phylum 5. Cyanobacteria [ 6Nostoc ] Classis 1(13). Gloeobacteres [ 5Gloeobacter ] 2(14). Chroobacteres [ 5Chroococcus ]7 3(15). Hormogoneae [ 5Nostoc ] Phylum 6. Bacteroidobacteria [ 6Bacteroides ]8 Classis 1(16). Fibrobacteres [ 5Fibrobacter ] 2(17). Chlorobi [ 5Chlorobium ] 3(18). Salinibacteres [ 5Salinibacter ] 4(19). Bacteroidetes [ 5Bacteroides ]9 Phylum 7. Spirobacteria [ 6Spirochaeta ] Classis 1(20). Spirochaetes [ 5Spirochaeta ] s.l.10 Phylum 8. Planctobacteria [ 6Planctomyces ]11 Classis 1(21). -

Systematic Botany 29(1):29-41. 2004 Doi

Systematic Botany 29(1):29-41. 2004 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1600/036364404772973960 Phylogenetic Relationships of Haplolepideous Mosses (Dicranidae) Inferred from rps4 Gene Sequences Terry A. Heddersonad, Donald J. Murrayb, Cymon J. Coxc, and Tracey L. Nowella aBolus Herbarium, Department of Botany, University of Cape Town, Private Bag, Rondebosch 7701, Republic of South Africa bThe Birmingham Botanical Garden, Westbourne Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 3TR U. K. cDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 dAuthor for Correspondence ( [email protected]) Abstract The haplolepideous mosses (Dicranidae) constitute a large group of ecologically and morphologically diverse species recognised primarily by having peristome teeth with a single row of cells on the dorsal surface. The reduction of sporophytes in numerous moss lineages renders circumscription of the Dicranidae problematic. Delimitation of genera and higher taxa within it has also been difficult. We analyse chloroplast-encoded rps4 gene sequences for 129 mosses, including representatives of nearly all the haplolepideous families and subfamilies, using parsimony, likelihood and Bayesian criteria. The data set includes 59 new sequences generated for this study. With the exception of Bryobartramia, which falls within the Encalyptaceae, the Dicranidae are resolved in all analyses as a monophyletic group including the extremely reduced Archidiales and Ephemeraceae. The monotypic Catoscopium, usually assigned to the Bryidae is consistently resolved as sister to Dicranidae, and this lineage has a high posterior probability under the Bayesian criterion. Within the Dicranidae, a core clade is resolved that comprises most of the species sampled, and all analyses identify a proto-haplolepideous grade of taxa previously placed in various haplolepideous families. -

A Revision of Schoenobryum (Cryphaeaceae, Bryopsida) in Africa1

Revision of Schoenobryum 147 Tropical Bryology 24: 147-159, 2003 A revision of Schoenobryum (Cryphaeaceae, Bryopsida) in Africa1 Brian J. O’Shea 141 Fawnbrake Avenue, London SE24 0BG, U.K. Abstract. The nine species and two varieties of Schoenobryum reported for Africa were investigated, and no characters were found that uniquely identified any of the taxa to be other than the pantropical Schoenobryum concavifolium. The following nine names become new synonyms of S. concavifolium: Cryphaea madagassa, C. subintegra, Acrocryphaea robusta, A. latifolia, A. subrobusta, A. tisserantii, A. latifolia var. microspora, A. plicatula and A. subintegra var. idanreense; a lectotype is selected for Acrocryphaea latifolia var. microspora P.de la Varde. INTRODUCTION as the majority have not been examined since the type description, and many have never been A recent checklist of Sub-Saharan Africa illustrated. (O’Shea, 1999) included nine species and two varieties of Schoenobryum, most of quite limited The purpose of this paper is to provide an distribution. Recent collecting in both Malawi overview of the genus worldwide, and to review (O’Shea et al., 2001) and Uganda (Wigginton et the taxonomic position of the African taxa. al., 2001) has shown the genus to be not uncommon, although there was only one CRYPHAEACEAE SCHIMP. 1856. previously published collection from the two countries (O’Shea, 1993). Apart from one Cryphaeaceae Schimp., Coroll. Bryol. Eur. 97. African taxon occurring in nine countries, the 1856 [‘1855’]. Type: Cryphaea D.Mohr in other 10 occurred in an average of 1.7 countries. F.Weber This particular profile is typical of unrevised genera in Africa, and indicative of a possible A brief review of the circumscription and need for revision (O’Shea, 1997), particularly systematics of the family, and the distinctions from related families (e.g. -

Antarctic Bryophyte Research—Current State and Future Directions

Bry. Div. Evo. 043 (1): 221–233 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & https://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.43.1.16 Antarctic bryophyte research—current state and future directions PAULO E.A.S. CÂMARA1, MicHELine CARVALHO-SILVA1 & MicHAEL STecH2,3 1Departamento de Botânica, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil UnB; �[email protected]; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3944-996X �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2389-3804 2Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands; 3Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9804-0120 Abstract Botany is one of the oldest sciences done south of parallel 60 °S, although few professional botanists have dedicated themselves to investigating the Antarctic bryoflora. After the publications of liverwort and moss floras in 2000 and 2008, respectively, new species were described. Currently, the Antarctic bryoflora comprises 28 liverwort and 116 moss species. Furthermore, Antarctic bryology has entered a new phase characterized by the use of molecular tools, in particular DNA sequencing. Although the molecular studies of Antarctic bryophytes have focused exclusively on mosses, molecular data (fingerprinting data and/or DNA sequences) have already been published for 36 % of the Antarctic moss species. In this paper we review the current state of Antarctic bryological research, focusing on molecular studies and conservation, and discuss future questions of Antarctic bryology in the light of global challenges. Keywords: Antarctic flora, conservation, future challenges, molecular phylogenetics, phylogeography Introduction The Antarctic is the most pristine, but also most extreme region on Earth in terms of environmental conditions. -

A Revised Red List of Bryophytes in Britain

ConservationNews Revised Red List distinguished from Extinct. This Red List uses Extinct in the Wild (EW) – a taxon is Extinct version 3.1 of the categories and criteria (IUCN, in the Wild when it is known to survive only in A revised Red List of 2001), along with guidelines produced to assist cultivation or as a naturalized population well with their interpretation and use (IUCN, 2006, outside the past range. There are no taxa in this 2008), further guidelines for using the system category in the British bryophyte flora. bryophytes in Britain at a regional level (IUCN, 2003), and specific Regionally Extinct (RE) – a taxon is regarded guidelines for applying the system to bryophytes as Regionally Extinct in Britain if there are no (Hallingbäck et al., 1995). post-1979 records and all known localities have Conservation OfficerNick Hodgetts presents the latest revised Red List for How these categories and criteria have been been visited and surveyed without success, or interpreted and applied to the British bryophyte if colonies recorded post-1979 are known to bryophytes in Britain. Dumortiera hirsuta in north Cornwall. Ian Atherton flora is summarized below, but anyone interested have disappeared. It should be appreciated that in looking into them in more depth should regional ‘extinction’ for bryophytes is sometimes he first published Red List of et al. (2001) and Preston (2010), varieties and consult the original IUCN documents, which less final than for other, more conspicuous bryophytes in Britain was produced subspecies have been disregarded. are available on the IUCN website (www. organisms. This may be because bryophytes are in 2001 as part of a Red Data Book 1980 has been chosen as the cut-off year to iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories- easily overlooked, or because their very efficient for bryophytes (Church et al., 2001). -

Fossil Mosses: What Do They Tell Us About Moss Evolution?

Bry. Div. Evo. 043 (1): 072–097 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & https://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.43.1.7 Fossil mosses: What do they tell us about moss evolution? MicHAEL S. IGNATOV1,2 & ELENA V. MASLOVA3 1 Tsitsin Main Botanical Garden of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 2 Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia 3 Belgorod State University, Pobedy Square, 85, Belgorod, 308015 Russia �[email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1520-042X * author for correspondence: �[email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6096-6315 Abstract The moss fossil records from the Paleozoic age to the Eocene epoch are reviewed and their putative relationships to extant moss groups discussed. The incomplete preservation and lack of key characters that could define the position of an ancient moss in modern classification remain the problem. Carboniferous records are still impossible to refer to any of the modern moss taxa. Numerous Permian protosphagnalean mosses possess traits that are absent in any extant group and they are therefore treated here as an extinct lineage, whose descendants, if any remain, cannot be recognized among contemporary taxa. Non-protosphagnalean Permian mosses were also fairly diverse, representing morphotypes comparable with Dicranidae and acrocarpous Bryidae, although unequivocal representatives of these subclasses are known only since Cretaceous and Jurassic. Even though Sphagnales is one of two oldest lineages separated from the main trunk of moss phylogenetic tree, it appears in fossil state regularly only since Late Cretaceous, ca. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Moss Occurrences in Yugyd Va National Park, Subpolar and Northern Urals, European North-East Russia

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32307 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e32307 Data Paper Moss occurrences in Yugyd Va National Park, Subpolar and Northern Urals, European North-East Russia Galina Zheleznova‡, Tatyana Shubina‡, Svetlana Degteva‡‡, Ivan Chadin , Mikhail Rubtsov‡ ‡ Institute of Biology of Komi Scientific Centre of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Syktyvkar, Russia Corresponding author: Tatyana Shubina ([email protected]) Academic editor: Yasen Mutafchiev Received: 10 Dec 2018 | Accepted: 25 Mar 2019 | Published: 01 Apr 2019 Citation: Zheleznova G, Shubina T, Degteva S, Chadin I, Rubtsov M (2019) Moss occurrences in Yugyd Va National Park, Subpolar and Northern Urals, European North-East Russia. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32307. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e32307 Abstract Background This study produced a dataset containing information on moss occurrences in the territory of Yugyd Va National Park, located in the Subpolar and Northern Urals, European North- East Russia. The dataset summarises occurrences noted by long-term bryological explorations in remote areas of the Subpolar and Northern Urals from 1943 to 2015 and from studies published since 1915. The dataset consists of 4,120 occurrence records. The occurrence data were extracted from herbarium specimen labels (3,833 records) and data from published literature (287 records). Most of the records (4,104) are georeferenced. A total of 302 moss taxa belonging to 112 genera and 36 families are reported herein to occur in Yugyd Va National Park. The diversity of bryophytes in this National Park has not yet been fully explored and further exploration will lead to more taxa. -

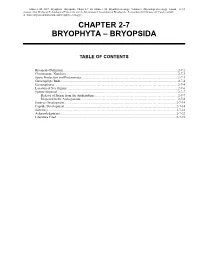

Volume 1, Chapter 2-7: Bryophyta

Glime, J. M. 2017. Bryophyta – Bryopsida. Chapt. 2-7. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook 2-7-1 sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 10 January 2019 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 2-7 BRYOPHYTA – BRYOPSIDA TABLE OF CONTENTS Bryopsida Definition........................................................................................................................................... 2-7-2 Chromosome Numbers........................................................................................................................................ 2-7-3 Spore Production and Protonemata ..................................................................................................................... 2-7-3 Gametophyte Buds.............................................................................................................................................. 2-7-4 Gametophores ..................................................................................................................................................... 2-7-4 Location of Sex Organs....................................................................................................................................... 2-7-6 Sperm Dispersal .................................................................................................................................................. 2-7-7 Release of Sperm from the Antheridium..................................................................................................... -

Bryological Times

The Bryological Times Volume 145 China – Australia International – In This Issue – Workshop for Karst Bryology in Guizhou, China, 3 rd – 7th August China – Australia International Workshop for Karst Bryology in Guizhou, China ........ 1 Alison Downing | Macquarie Another field-observation of a possible springtail-mediated moss sperm transfer University | Sydney, Australia | [email protected] ................................................................................. 5 At the bicentennial of Richard Spruce's Pina (Josephine) Milne | Royal birth ....................................................................... 6 Botanic Garden | Melbourne, IAB awardees ..................................................... 9 Australia | [email protected] Bryophyte Inventory for Rainy Pass ....... 10 The World Heritage listed South China Karst Curso-taller sobre hepáticas tropicales 11 2 encompasses about 550,000 km of subtropical to Report from the recipient of the 2017 tropical karst in Guizhou, Guangxi, Yunnan and Stanley Greene Award: Ecophysiological Chongqing provinces. The karst terrain includes specialization to climate .............................. 12 tower, cone and pinnacle karst, together with News from Australasia ................................. 13 massive caves, natural bridges, deep gorges, enormous sinkholes, karst waterfalls and News from the Spanish Bryological disappearing streams. Mountain slopes and peaks Society ............................................................... 14 are clothed in dark green -

Part 2 – Fruticose Species

Appendix 5.2-1 Vegetation Technical Appendix APPENDIX 5.2‐1 Vegetation Technical Appendix Contents Section Page Ecological Land Classification ............................................................................................................ A5.2‐1‐1 Geodatabase Development .............................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐1 Vegetation Community Mapping ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐1 Quality Assurance and Quality Control ............................................................................ A5.2‐1‐3 Limitations of Ecological Land Classification .................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Field Data Collection ......................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Supplementary Results ..................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐4 Rare Vegetation Species and Rare Ecological Communities ........................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Supplementary Desktop Results ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Field Methods ................................................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐16 Supplementary Results ................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐17 Weed Species