University of the Witwatersrand Institute for Advanced Social Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Site Development Plans Standard Operating Procedures for COVID

NELSON MANDELA BAY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY NOTICE SITE DEVELOPMENT PLAN APPLICATIONS (SDP) STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES FOR DURING COVID-19 PERIOD A. SITE DEVELOPMENT PLANS (SDPs) 1. SDP applications are to be converted into PDF format PDF (not exceeding 2mb) and submitted per email to the Planning Support Officer Ms N Ketelo at: [email protected], who will in turn acknowledge receipt of the application per email. 2. In the event that the attachments combined exceeds the prescribed size, the application must be split into separate emails or put in a flash-drive to be delivered to Land Planning Division in 3rd Floor Lillian Diedericks Building, 191 Govan Mbeki Avenue, Port Elizabeth, preferably on appointment. 3. Documents must be labelled Annexure A, B, C…etc. as guided by the table appended hereto showing documents required. 4. An assessment sheet will be emailed back to an applicant by a Town Planner dealing with the SDP. 5. It is the responsibility of an applicant to obtain comments from various municipal departments. 6. An applicant must make amendments to the plan as per comments received from various municipal departments, if required. 7. An applicant must submit the plan and the assessment sheet in PDF (email or flash-drive) to a Town Planner dealing with SDP through email. 8. A Town Planner will acknowledge receipt, finalize the SDP and communicate the outcome to an applicant through a correspondence sent via email. B. TOWN PLANNING COMMENTS ON BUILDING PLANS 1. Technical Controllers responsible for Town Planning related comments made on building plans will be available on Thursdays for inquiries at 3rd Floor Lillian Diedericks Building, Govan Mbeki Avenue, Port Elizabeth. -

Luc Strydom Environmental Consultant

SRK Consulting Page 1 Luc Strydom Environmental Consultant Profession Environmental Scientist Education BA Environmental Management, University of South Africa, 2015 Registrations/ Registered EAP, EAPASA (2020/1504) Affiliations Certificated Natural Scientist (EIA), SACNASP (Reg No. 120385) Member, South African Wetland Society (Membership No.: 193665) Member, International Association of Impact Assessors, South Africa (IAIAsa), Volunteer, Custodians of Rare and Endangered Wildflowers (CREW). Specialisation Wetland and aquatic impact assessments, botanical surveys, vegetation impact assessments, invasive alien monitoring and control plans, rehabilitation plans, environmental impact and basic assessments, environmental management programmes (EMPrs), water use license applications (WULAs), environmental auditing (environmental control officer), geo-hydrological sampling, section 24G applications & GIS systems. Expertise Luc Strydom has previous experience in GIS, working for Setplan PE, a town planning consultancy group. His expertise in GIS includes map production, data capturing, data manipulation, data acquisition and database management. Luc has developed his skills and expertise over the years as he has been involved in many different types of environmental projects, such as: • environmental impact assessments (EIAs); • wetland and aquatic impact assessments (wetland screening, delineation, PES & EIS determination, ecosystem services assessment, etc.); • environmental management plans/programmes (EMPr); • environmental auditing (acting -

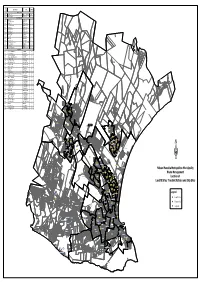

Map of Landfill Transfer and Skip Sites

Origin DESCRIPTION AREA WARD Code LANDFILL SITES G01 ARLINGTON PORT ELIZABETH 01 G02 KOEDOESKLOOF UITENHAGE 53 TRANSFER SITES G03 TAMBO STR McNAUGHTON 50 G04 GILLESPIE STR EXT UITENHAGE 53 G05 JOLOBE STR KWANOBUHLE 47 G06 ZOLILE NOGCAZI RD KWANOBUHLE 45 G07 SARILI STR KWANOBUHLE 42 G08 VERWOERD RD UITENHAGE 51 G09 NGEYAKHE STR KWANOBUHLE 42 G10 NTAMBANANI STR KWANOBUHLE 47 G11 LAKSMAN AVE ROSEDALE 49 G12 RALO STR KWAMAGXAKI 30 G13 GAIL ROAD GELVANDALE 13 G14 DITCHLING STR ALGOA PARK 11 G15 CAPE ROAD - OPP HOTEL HUNTERS RETREAT 12 G16 KRAGGAKAMA RD FRAMESBY 09 G17 5TH AVENUE WALMER 04 G18 STRANDFONTEIN RD SUMMERSTRAND 02 SKIP SITES G19 OFF WILLIAM MOFFAT FAIRVIEW 06 G20 STANFORD ROAD HELENVALE 13 G21 OLD UITENHAGE ROAD GOVAN MBEKI 33 G22 KATOO & HARRINGTON STR SALTLAKE 32 G23 BRAMLIN STREET MALABAR EXT 6 09 G24 ROHLILALA VILLAGE MISSIONVALE 32 G25 EMPILWENI HOSPITAL NEW BRIGHTON 31 G26 EMLOTHENI STR NEW BRIGHTON 14 G27 GUNGULUZA STR NEW BRIGHTON 16 G28 DAKU SQUARE KWAZAKHELE 24 G29 DAKU SPAR KWAZAKHELE 21 G30 TIPPERS CREEK BLUEWATER BAY 60 G31 CARDEN STR - EAST OF RAILWAY CROSSING REDHOUSE 60 G32 BHOBHOYI STR NU 8 MOTHERWELL 56 G33 UMNULU 1 STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 58 Farms Uitenhage G34 NGXOTWANE STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 57 G51 ward 53 S G35 MPONGO STR NU 7 MOTHERWELL 57 G36 MGWALANA STR NU 6 MOTHERWELL 59 G37 DABADABA STR NU 5 MOTHERWELL 59 G38 MBOKWANE NU 10 MOTHERWELL 55 Colchester G39 GOGO STR NU 1 MOTHERWELL 56 G40 MALINGA STR WELLS ESTATE 60 G41 SAKWATSHA STR NU 8 MOTHERWELL 58 G42 NGQOKWENI STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 57 G43 UMNULU 2 STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL -

Aia) for the Proposed Mixed-Use Housing Development, Kwanobuhle, Extension 11, Uitenhage, Nelson Mandela Bay Muncipality, Eastern Cape Province

A PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMAPCT ASSESMENT (AIA) FOR THE PROPOSED MIXED-USE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT, KWANOBUHLE, EXTENSION 11, UITENHAGE, NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNCIPALITY, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE Prepared for: SRK Consulting PO Box 21842 Port Elizabeth 6000 Tel: 041 509 4800 Fax: 041 509 4850 Contact person: Ms Karissa Nel Email: [email protected] Compiled by: Dr Johan Binneman, Ms Celeste Booth and Ms Natasha Higgitt Department of Archaeology Albany Museum Somerset Street Grahamstown 6139 Tel: (046) 622 2312 Fax: (046) 622 2398 Contact person: Ms. Celeste Booth Email: [email protected] July 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 3. BRIEF ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND 6. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPERTY 7. ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION 8. CULTURAL LANDSCAPE 11. RECOMMENDATIONS 12. GENERAL REMARKS AND CONDITIONS 13. APPENDIX A 14. MAP 1 16. MAP 2 17. MAP 3 18. TABLE 1 19. 2 A PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMAPCT ASSESMENT (AIA) FOR THE PROPOSED MIXED-USE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT, KWANOBUHLE, EXTENSION 11, UITENHAGE, NELSON MANDELA BAY MUNCIPALITY, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE Note: This report follows the minimum standard guidelines required by the South African Heritage Resources Agency for compiling a Phase 1 Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of the Study The purpose of the study was to conduct a phase 1 archaeological impact assessment (AIA) for the proposed mixed-use housing development, Kwanobuhle Extension 11, Uitenhage, Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, Eastern Cape Province. The survey was conducted to establish the range and importance of the exposed and in situ archaeological heritage materials and features, the potential impact of the development, and to make recommendations to minimize possible damage to these sites. -

Land Use Management System for the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality

TOWARDS A NEW LAND USE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR THE NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY COMPONENT 1 : ANALYSIS & POLICY DIRECTIVES PHASES 1, 2 & 3 OUTCOMES REPORT (1ST DRAFT : FEBRUARY 2005) Prepared by: Prepared for: Business Unit Manager: Housing and Land Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality Mr J. van der Westhuysen i Executive Summary 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION Drafting of a New Land Use Management System (LUMS) for the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality, which should include as a minimum requirement a single zoning scheme for the Metro‟s area of jurisdiction, has been identified as a priority project in the Metro‟s 2003/4 Integrated Development Plan (IDP). 1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT With the amalgamation of the Rural Areas, Uitenhage, Despatch and Port Elizabeth, in 2000, the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality inherited twelve (12) different sets of zoning schemes. These zoning schemes are currently administered and implemented by the Municipality and in some cases delegation vests with the Department of Housing, Local Government and Traditional Affairs. These zoning schemes, some dating back to 1961, were prepared and promulgated in terms of various sets of legislation, i.e. the Land Use Planning Ordinance and the regulations promulgated in terms of the Black Communities Development Act. In many respects, these existing zoning schemes are inappropriate and outdated and therefore do not respond to current and identified future land development and conservation needs. The White Paper on Spatial Planning and Land Use Management clearly summarises shortfalls relating to land use planning and management in general: . Disparate Land Use Management Systems in Former “Race Zones” . Old and outdated Land Use Management . -

Download Resource Register

Province of the EASTERN CAPE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Private Bag / Privaatsak X3906, Struanway, Struandale, Port Elizabeth, 6056 Tel. No. (041) 4065732 - Fax. No. (041) 4511729 / 4513458 [email protected] NELSON MANDELA METROPOLE DISTRICT OFFICE RESOURCE REGISTER July 2008 The District Manager 041-4065701 041-4513458 Department of Social Development Private Bag x3906 Port Elizabeth 6056 Programme Management Unit 041- 4065700 041-4513458 People with special needs (disability, older 041-4065700 041-4513458 persons, substance abuse) Substance abuse and disability 041-4065700 041-4513458 Older persons 041-4065700 041-4513458 Women and Victim Empowerment 041-4065700 041-4513458 HIV/AIDS 041-4065700 041-4513458 Child, Youth, family 041-4065700 041-4513458 Early Childhood Development 041 406 5700 041 4511729 041 406 5782 Development services 041-4065700 041-4513458 2 DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT NELSON MANDELA METROPOLE DISTRICT COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CENTRES SERVICES OFFERED: Development, Care & Protection of Vulnerable People in the Community OFFICE POSTAL ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS TEL. NO. FAX. AREAS NO. UITENHAGE P.O. Box 538, Uitenhage Spoornet Building 9228838 9228957 Uitenhage, Despatch and surrounding rural area 6230 Stow Road (Amanzi, Cockscomb, Kruis River Elands River) Uitenhage ZWIDE Private bag X 3906, Port Struanway, New Brighton 4065700 4511729 Kwazakhele, North of Daku Road, Kwadesi, Elizabeth 6056 Kwamagxaki, Zwide, Missionvale, Joe Slovo, Govan Mbeki BETHELSDORP Private bag X 3906, Port Straunway, -

Domestic Groups

DOMESTIC GROUPS Group 1 Area 1 (Old Group 1 - Area 1) Motherwell North Motherwell North of Addo Rd Motherwell NU1 -12 Tjoksville Group 2 Group 2 Area 2 (Old Group 1 - Area 3) Area 3 (Old Group 1 - Area 2) 7de Laan Khayamnandi Aspen Heights San Soucci Booysens Park Chatty Ext 21 -34 Heath Park (Above Spar and including PE College) Jacksonville Kleinskool Kwanoxolo Palm Ridge Group 3 Group 3 Area 4 (Old Group 2 - Area 4) Area 5 (Old Group 2 - Area 5) Arcadia Buffelsfontein Rd Bethelsdorp Village Buffelsfontein Old Age Home Chatty Charlo Cleary Estate Circular Drive Cleary Park Fairview Ext 28 (St. Elizabeth Street area) Greenshields Park Heugh Rd – 6th Ave to William Hillside Moffett Heath Park (Bethelsdorp Side and around PE College) Mangold Park (Section) Hillside Mount Pleasant Kleinskool Overbaakens NMMU (Vista) Springfield Salsoneville Walmer 6th Ave to William Salt Lake Moffett Sanctor Walmer Downs West End William Moffett Windvogel Group 4 Group 4 Area 6 (Old Group 3 - Area 7) Area 7 (Old Group 3 - Area 7) Kwanobuhle Winterhoek Park Rocklands lines S, SE, SW Van Estate (section) Strelitzia Park Extention Gerald Smith Rosedale Tambo Thomas Gamble Group 5 Area 8 (Old Group 3 - Area 9) EP Command Forest Hill Humewood South End Southdene Summerstrand up to Marine Hotel Group 6 Group 6 Area 9 (Old Group 4 - Area 10) Area 10 (Old Group 4 - Area 12) Malabar Albany Rd Area Central Area Russell Rd to Malabar Ext 6 Albany Rd City Centre Whites Rd to Gelvandale (closer to Gail Rd) Russell Rd Helenvale Govan Mbeki to City to Albany Richmond -

Survey of Heavy Metals in the Sediments of the Swartkops River Estuary, Port Elizabeth South Africa

Survey of heavy metals in the sediments of the Swartkops River Estuary, Port Elizabeth South Africa Karen Binning and Dan Baird* Zoology Department, University of Port Elizabeth, PO Box 1600, Port Elizabeth 6000, South Africa Abstract Elevated levels of heavy metals in the sediment can be a good indication of man-induced pollution. Concentrations of chrome, lead, zinc, titanium, manganese, strontium, copper and tin were measured in the sediments taken along a section of the Swartkops River and its estuary. These results showed that the highest heavy metal concentrations in both the estuary and river were recorded at points where runoff from informal settlements and industry entered the system. Comparison of the results for the estuary with those obtained in a similar survey made about 20 years ago revealed some remarkable increases. This raises concern over the long-term health of the Swartkops River ecosystem. Introduction pollution in a particular region or ecosystem. Heavy metal concentrations in the water column can be relatively low, but the The Swartkops River flows through a highly urbanised and concentrations in the sediment may be elevated. Low level discharges industrialised region of the Eastern Cape and forms an integral part of a contaminant may meet the water quality criteria, but long-term of Port Elizabeth and the surrounding areas. It is a valuable partitioning to the sediments could result in the accumulation of recreational and ecological asset, but owing to the rapidly expanding high loads of pollutants. It has been estimated that about 90% of urban areas, it is subject to the effects and influences of these particulate matter carried by rivers settles in estuaries and coastal developments. -

2020 1. Size of Nelson Mandela Bay's Residential Property Market

NELSON MANDELA BAY Housing Market Report - 2020 1. Size of the residential property market Summary: There are approximately 368 520 households in Nelson Mandela Bay 2. Impact of COVID-19 (NMB). The city’s residential property market includes rental properties, where 3. Government-subsidised properties (GSP) more than one family might live in a property with a single title deed – for example, a high-rise building. In addition, there are an estimated 38 000 4. Residential transactions — new build households living in informal settlements.1 These are not reflected in this data, 5. Residential transactions — resale which only considers formally registered residential properties. 6. Residential transactions — GSP NMB’s residential property market was valued at R136.7 billion in 2019, with 67% 7. First-time homeowners/buyers of properties valued at R600 000 or less. 42% are government-subsidised—the 8. Housing finance — new vs resale largest share of all the metros. The contribution of government housing (75%) was evident in the entry market. Only 9% of total transactions were new build 9. Housing finance — by lender properties, while the resale market was more active. FNB and Standard Bank 10. Freehold vs. sectional title properties issued the largest share of their bonded transactions for properties valued below 11. Comparing across metros R300 000. Overall, bonded transactions in the entry market are expected to 12. Report methodology remain low due to unequal economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. 1. Size of Nelson Mandela Bay’s residential property market In 2019, there were 239 181 residential properties on the deeds registry in Nelson Mandela Bay (NMB), making up 35.1% of the total residential properties in the Eastern Cape province. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103960 Fonteine Park Apteek 115 Da Gama Rd, Ferreira Town, Jeffreys Bay Sarah Baartman DM Eastern Cape 202103949 Mqhele Clinic Mpakama, Mqhele Location Elliotdale Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103754 Masincedane Clinic Lukhanyisweni Location Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103840 ISUZU STRUANWAY OCCUPATIONAL N Mandela Bay MM CLINIC Eastern Cape 202103753 Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103725 Pricesdale Clinic Mbekweni Village Whittlesea C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103724 Lubisi Clinic Po Southeville A/A Lubisi C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103721 Eureka Clinic 1228 Angelier Street 9744 Joe Gqabi DM Eastern Cape 202103586 Bengu Clinic Bengu Lady Frere (Emalahleni) C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103588 ISUZU PENSIONERS KEMPSTON ROAD N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape 202103584 Mhlanga Clinic Mlhaya Cliwe St Augustine Jss C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103658 Westering Medicross 541 Cape Road, Linton Grange, Port Elizabeth N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103581 Tsengiwe Clinic Next To Tsengiwe J.P.S C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103571 Askeaton Clinic Next To B.B. Mdledle J.S.School Askeaton C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103433 Qitsi Clinic Mdibaniso Aa, Qitsi Cofimvaba C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103227 Punzana Clinic Tildin Lp School Tildin Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103186 Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Aa Libode O Tambo DM Eastern Cape 202103214 Lotana Clinic Next To Lotana Clinic Lotana -

(Gp) Network List Eastern Cape

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND GENERAL PRACTITIONER (GP) NETWORK LIST EASTERN CAPE PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME DISPENSING PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ABERDEEN 1582054 MULLER YES 22 VOORTREKKER STREET, ABERDEEN ABERDEEN 049 8460618 ADDO 468606 GXAMZA YES SHOP 3 MAIN STREET, LORRAINE ADDO 041 3671406 ALICE 1536117 ANJUM YES OLD TABA OFFICE, 2 GARDEN STREET, ALICE ALICE 040 6531314 BETHELSDORP 1511394 SONAVANE YES 184 BOOYSEN PARK DRIVE, BOOYSENS PARK BETHELSDORP 041 4831242 BETHELSDORP 1518968 SCHARNECK YES 2 WILLIAM SLAMMERT DRIVE, BLOEMENDAL BETHELSDORP 041 4815271 BETHELSDORP 1532901 VAN STAADEN YES 40 SCHOLTZ STREET, BLOEMENDAL BETHELSDORP 041 4816163 BETHELSDORP 1557432 JAGA YES SANCTOR MEDICAL CENTRE, 48 MAROCK ROAD, SANCTOR BETHELSDORP 041 4812161 BETHELSDORP 1443925 MANGA YES SANCTOR MEDICAL CENTRE, 48 MAROCK ROAD, SANCTOR BETHELSDORP 041 4812161 BETHELSDORP 1458531 PARUK YES UNIT 86 CLEARY PARK CENTRE, CLEARY PARK BETHELSDORP 041 4816076 BETHELSDORP 1462598 BAWASA YES SHOP 1 WEST END SHOPPING CENTRE, ST ANNE STREET, WEST END BETHELSDORP 041 4814027 BIZANA 145440 NKALANE YES SHOP 4 STEADY CENTRE, THOMPSON AVENUE, BIZANA BIZANA 039 2510171 BUTTERWORTH 1515179 MAFUYA YES BUTTERWORTH MEDICAL CENTRE, 30 MERRIMAN STREET, BUTTERWORTH BUTTERWORTH 047 4914455 CATHCART 1545213 RICHARDSON YES 37 HEMMING STREET, CATHCART CATHCART 045 8431052 CRADOCK 1586432 SLABBERT YES 31 VICTORIA STREET, CRADOCK CRADOCK 048 8810068 CRADOCK 562459 H A NEETHLING INCORPORATED YES 73 ADDERLEY STREET, CRADOCK CRADOCK 048 8811670 DESPATCH 1432842 -

Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title South Africa: On the Verge of Revolution Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2d3649kd Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 15(1-2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Magubane, Bernard Publication Date 1986 DOI 10.5070/F7151-2016992 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SOUTH AFRICA: ON THE VERGE OF REVOLUTION? Bernard Magubane Between the anvil of mass United action and the hammer of armed struggle, we shall crush white minority rule. Nelson Mandela History will remember the years 1975 and 1985 as a period of far-reaching upheavals in Southern Africa. They are the years when the white re-doubt began to crumble as tumultuous struggles shook the minority regime to its very foundation . Today, the white settler state of South Africa is like a city built on a fault-line -- every shift of the rocks weakens the foundations of every structure, and not just parts of it. An editorial in the Sunday Tribune (1/20/85) summing the current political crisis 1n South Africa states that: The sixties were the granite years of apartheid. Those ye1rs are decfdedly out, for no longer does the Government hold with righteous fervor the belief that the equitable solution to race differences is the policy of separation. The apartheid creed, however, has been surely eroded, not replaced. The talk of reform is all flim-flam: it is the grudging make-do solution of the solely pressed, rather than a clear vision based on the philosophical rejection of racial domination.