Environmental Factors Affecting Waterfowl in the Suisun Area, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6439/docket-no-fws-hq-nwrs-2019-0040-fxrs12610900000-190-ff09r20000-6439.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 09/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-18054, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333-15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Parts 26, 32, 36, and 71 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000] RIN 1018-BD79 2019–2020 Station-Specific Hunting and Sport Fishing Regulations AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), open seven National Wildlife Refuges (NWRs) that are currently closed to hunting and sport fishing. In addition, we expand hunting and sport fishing at 70 other NWRs, and add pertinent station-specific regulations for other NWRs that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing for the 2019–2020 season. We also formally open 15 units of the National Fish Hatchery System to hunting and sport fishing. We also add pertinent station- specific regulations that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing at these 15 National Fish Hatcheries (NFHs) for the 2019–2020 season. This rule includes global administrative updates to every NWR entry in our refuge- specific regulations and the reorganization of general public use regulations. We remove approximately 2,100 regulations that will have no impact on the administration of hunting and sport fishing within the National Wildlife Refuge System. We also simplify over 2,900 refuge- specific regulations to comply with a Presidential mandate to adhere to plain language standards 1 and to reduce the regulatory burden on the public. -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Wednesday, September 8, 2004 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Parts 31 and 32 2004–2005 Refuge-Specific Hunting and Sport Fishing Regulations; Final Rule VerDate jul<14>2003 17:08 Sep 07, 2004 Jkt 203001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\08SER2.SGM 08SER2 54350 Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 173 / Wednesday, September 8, 2004 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR regulations to ensure the continued Act (Recreation Act) of 1962 (16 U.S.C. compatibility of hunting and sport 460k–460k–4) govern the administration Fish and Wildlife Service fishing programs and to ensure that and public use of refuges. these programs will not materially Amendments enacted by the National 50 CFR Parts 31 and 32 interfere with or detract from the Wildlife Refuge System Improvement RIN 1018–AT40 fulfillment of refuge purposes or the Act of 1997 (Improvement Act) build Refuge System’s mission. upon the Administration Act in a 2004–2005 Refuge-Specific Hunting Provisions governing hunting and manner that provides an ‘‘organic act’’ and Sport Fishing Regulations sport fishing on refuges are in Title 50 for the Refuge System similar to those of the Code of Federal Regulations in that exist for other public Federal lands. AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, part 32 (50 CFR part 32). We regulate The Improvement Act serves to ensure Interior. hunting and sport fishing on refuges to: that we effectively manage the Refuge ACTION: Final rule. • Ensure compatibility with refuge System as a national network of lands, purpose(s); waters, and interests for the protection SUMMARY: The Fish and Wildlife Service • Properly manage the fish and and conservation of our Nation’s adds 10 new refuges and wetland wildlife resource(s); wildlife resources. -

2019-2020 Station-Specific Hunting and Fishing Proposed Rule Signed

Billing Code 4333-15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Parts 26, 32, 36, and 71 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000] RIN 1018-BD79 2019–2020 Station-Specific Hunting and Sport Fishing Regulations AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to open seven National Wildlife Refuges (NWRs) that are currently closed to hunting and sport fishing; two of these NWRs would be newly open to both hunting and sport fishing, three would be newly open only to hunting, and two would be newly open only to sport fishing. In addition, we propose to expand hunting and sport fishing at 67 other NWRs, and add pertinent station-specific regulations for other NWRs that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing for the 2019–2020 season. We also propose to formally open 15 units of the National Fish Hatchery System (NFHs) to hunting and sport fishing; one of these would be open to both hunting and sport fishing, 2 would be open only to hunting, and 12 would be open only to sport fishing. We also propose to add pertinent station-specific regulations that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing at these 15 NFHs for the 2019–2020 season. 1 Through these openings and expansions, we are proposing to open or expand an additional 1,451,131 acres to hunting and sport fishing within the National Wildlife Refuge System and the National Fish Hatchery System. -

Gentry Suisun Draft EIR Vol II

Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX A- EXISTING TRAFFIC COUNTS 162 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX B- EXISTING LOS RESULTS 163 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX C- EXISTING PLUS APPROVED LOS RESULTS 164 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX D- MODEL DOCUMENTATION 165 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX E- CUMULATIVE LOS RESULTS 166 Administrative Draft EIR Suisun Gentry Project February 10, 2006 4.8 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES INTRODUCTION This section of the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) evaluates potential biological resource impacts associated with the implementation of the Proposed Suisun Gentry Project and includes a discussion of the mitigation measures necessary to reduce impacts to a less-than-significant level where possible. The information contained in this analysis is primarily based upon the Biological Assessment, Gentry-Suisun Project, City of Suisun City, Solano County, California prepared by The Huffman-Broadway Group (2006) and the Wetland Delineation and Special- Status Species Survey Report prepared by Vollmar Consulting (2003). Additional details on plant and wildlife species presence are based upon field surveys performed by Foothill Associates’ biologists. This report describes the habitat types, jurisdictional waters, and presence/absence of special-status plants and animals at the Proposed Project area and provides a review of existing literature, maps, and aerial photography pertaining to the biological resources of the area. It also evaluates potential impacts of the proposed Project in relation to CEQA and other environmental laws, and provides mitigation recommendations. Foothill Associates has prepared this Section of the EIR for the proposed Suisun Gentry Project (Project) in central Solano County, California. -

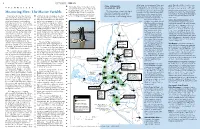

Measuring Flow

6 JUNE 2012 ESTUARY NEWS delta from the Sacramento River, was north. Typically, Old River is saltier than call the big “noise” of the tides. At the NETWORK answered with the installation of the Middle River at this location, suggesting TECHNOLOGY Jersey Point Station, for example, daily SNAPSHOT first hydro-acoustic meter at Freeport the former carries the lion’s share of the water from the western delta. The 14-day peak tidal flows can be on the order The flow station network developed in 1978. A decade later, water manag- Measuring Flow: The Master Variable of 150,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), ers and scientists wanted to monitor average of the sum of the Old and Middle over time in response to a series of River flows is known as OMR and appears while the net flow may be 2,000 cfs or questions. The first question, how the influence of the export facilities Stand on a tule island at the junc- and federal water managers use flow less. According to Burau, this means on the north-to-south movement of in numerous regulatory documents and much fresh water was flowing into the court cases. tion of two delta channels and you’d station network data to make critical continued to page 8 water from central to south delta. So think you could tell which way the daily decisions about how much fresh they installed two more Sutter-Steamboat Corridor - Sutter water was flowing. Surely anything water they can pump to cities and 122°00' 121°45' 121°30' 121°15' acoustic velocity meters at and Steamboat Sloughs are significant that looks so much like a river natu- farms, and when and where. -

SAN JOAQUIN COUNTY MULTI-SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION and OPEN SPACE PLAN (SJMSCP) November 14, 2000

SAN JOAQUIN COUNTY MULTI-SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE PLAN (SJMSCP) November 14, 2000 November 14, 2000 THIS PAGE BLANK November 14, 2000 Funding for this document was provided by a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation with assistance from the San Joaquin County Transportation Authority, the City of Tracy, and the City of Lathrop November 14, 2000 THIS PAGE BLANK November 14, 2000 SJMSCP STEERING COMMITTEES, STAFF AND TECHNICAL SUPPORT HABITAT POLICY ADVISORY COMMITTEE Phillip Pennino, Chair City of Lodi Robert Cabral, Vice Chair San Joaquin County Board of Supervisors Ron Addington Business Dan Gifford/Robert Mapes/Dave Zezulak/Terry Roscoe California Department of Fish and Game Mitch Hayden U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waldo Holt Conservation William Lehman/Sheila Larsen/Peter Cross/Robert Pine/Ken Fuller/Mike Horton Cay Goude/Jan Knight/Ann Chrisney/Vicki Campbell/Jim Browning U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Brad Lange Agriculture Bruce Mettler Agriculture Tonie Marie Raymus Business Martha Shaver Land Trusts Steve Stocking Conservation Doug Unruh Business HABITAT STAFF WORKING GROUP Margit Aramburu Delta Protection Commission Luis Arismendi/Don Cose Business Mike Brown Aggregate Mining Ben Cantu Manteca Pam Carder Lathrop John Carlson/Mike Niblock Stockton Dan Gifford/Robert Mapes/Dave Zezulak/ Terry Roscoe California Department of Fish and Game Brian Millar/Barry Hand Tracy Mitch Hayden U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waldo Holt Conservation William Lehman/Sheila Larsen/Peter Cross/Robert Pine/Ken Fuller/Mike Horton/ Cay Goude/Jan Knight/Ann Chrisney/Vicki Campbell/Jim Browning U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Peggy Keranen/Kitty Walker San Joaquin County Rad Bartlam/David Morimoto Lodi Dale Steele, Gina Moran Caltrans Ernest Tyhurst Ripon Julia E. -

Taking a Gantble on Gantbell

The Newsletter of the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society September 2000 Taking a Gantble on Gantbell Another Alaskan Adventure Sunday morning dawned, if there ever is couch, in the midst of about 30 other by Jack Cole a dawn in the summer in Alaska, cold and birders, waiting for yet another hourly How many disgruntled birders does it foggy. That should have been a clue, yet announcement of the weather in Gambell. take to fill the tiny terminal of Bering Air we taxied to the airport with every expec Between announcements we dashed out in Nome, Alaska? Little did we know tation of departing for Gambell at the to nearby birding spots, with Mike in the when we so carefully made our plans last scheduled hour of 10 AM. Four birders in pickup bed, as another day appeared to year that we would be part of the answer. the lounge in their second day of waiting be wasting away. After lunch we even Ed Frost and I left for Nome, and should have been our next clue. When we called Alaska Airlines to investigate al eventually Gambell, at 6:50 AM on Sat met a young man on his FOURTH day of ternate flights home. Finally, at 2:30, the urday, May 27, on what would be the first waiting to return to his home in Gambell, word came down: "We're going to try of ten flights on the last warm day we reality set in. We had a problem! Every it!" Bering Air brought their six planes would see in a week . -

A Systematic and Ecological Study of Nearctic Hydrellia Diptera: Ephydridae)

D. L. DEONU A Systematic and Ecological Study of Nearctic Hydrellia Diptera: Ephydridae) SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY NUMBER 68 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti- tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge not strictly professional." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to ^oology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. Each publica- tion is distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, institutes, and interested specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smith- sonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. S. DILLON RIPLEY Secretary Smithsonian Institution SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY NUMBER 68 A Systematic and Ecological Study of Nearctic Hydrellia (Diptera: Ephydridae) SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON 1971 ABSTRACT Deonier, D. -

University of California Archaeological Survey No

Reports of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY NO. 68, PART Ill ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES III. ETHNOLOGICAL NOTES ON CENTRAL CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES C. Hart Merriam Compiled and Edited by Robert F. Heizer University of California Archaeological Research Facility Department of Anthropology Berkeley December 1967 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES III. ETHNOLOGICAL NOTES ON CENTRAL CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES PART I. ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES PART II. ETHNOLOGICAL NOTES ON NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES Acknowledgment is made to Dr. S. Dillon Ripley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, of a grant from the E. H. Harriman Fund for partial support of the publication of REPORT No. 68, Parts I, II, III. REPORTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY NO. 68, PART III ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES III. ETHNOLOGICAL NOTES ON CENTRAL CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES C. HART MERRIAM Compiled and Edited by Robert F. Heizer UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH FACILITY Department of Anthropology Berkeley December 1967 CONTENTS WINTOON FIELD WORK AMONG THE WINTOON 257 CLASSIFICATION OF WIN-TOON STOCK 259 ETHNOBOTANY . 263 FOODS 265 NOM -LAK- KE VILLAGES 266 POc -E-WIN TRIBE OF WINTOON STOCK 270 CHOO-HEL'-NEM-SEL NOTES 272 KO-ROO VILLAGES ON MOUNDS 281 POMO MAH-KAHIV-MO CHUM-MI OF CLOVERDALE VALLEY 282 SHO-KO-A'H OF HOPLAND . a 283 ME-TUM'-MAH OF LITTLE LAKE VALLEY 286 HRAM-FO 295 YOKIAH POMO 299 BO-YAH 303 MIDOO FIELD WORK AJMONG MIDUAN TRIBES 305 KUM-MO -WIN . 313 MI-CHOPW-DO 314 NE -CE-NON 319 NIS'-SIM PA/-WE-NAN 320 MEWUK CLASSIFICATION OF NEWAN STOCK 323 FIELD WORK AMONG THE ME'-WUK 325 SOUTHERN MEWUK . -

June 2012 Vol

ESTUARY 1 science • restoration • watershed • politics • species • Bay RECYCLING OUTSIDE san Francisco estuary partnership THE ESTUARY NEW GREY BOX REAS IN A THE Waterless PLUMBIThereng CODE was no sign of shirking Water Closets? NEWS Advocates of water when 50 school kids began Never mind the wh digging holes and planting buckeye saplings at the former Hamilton airbase. These kids weren’t just playing at restoration, they were actually doing it.... see p.3 NEWS JUNE 2012 Vol. 21, no. 3 INSIDE Kids Plant Trees . .3 Bird and Vet Refuge . 4 Goofy Sturgeon . .5 Delta Flow Stations . .6 Legendary Lady . .9 Grey Water . 10 2 JUNE 2012 3 ESTUARY NEWS YOUTH e d U c a t i o n SPEAKS BRIEFS BALLAST WATER BELT- NATIVE WATERSHED TIGHTENING: Federal agencies are VEGETATION RESEARCH: A new Watershed tightening controls on ballast water, US Forest Service classification of a major vector for invasive aquatic watershed conditions in the National Kids Dig Futures at a Glance species on the West Coast. The US Forests is paving the way for more Saving Coast Guard’s new standard for the research on vegetation condition Fifty kids from fourth and second “I like knowing that I’m helping allowable concentration of living and invasive species spread. As a grades scattered across a barren the environment,” said fourth- the World SMELT HOTEL AT DAVIS: Delta smelt organisms in discharged water took result, the California Native Plant field on a recent spring morning to grader Sriha Srinivasan. Other are picky when it comes to things like effect June 21, 2012. -

United States Department of the Interior SERVICE

£el~ MAR 2 7 2019 U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE United States Department of the Interior SERVICE FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE San Francisco Bay-Delta Fish and Wildlife Office 650 Capitol Mall, Suite 8-300 Sacramento, California 95814 In reply refer to: 08FBDT00-2017-F-0098-1 MAR ,21 2019 Mark T. Ziminske Chief, Environmental Resources Branch Department of the Anny Corps of Engineers, Sacramento District 13 25 J Street Sacramento, CA 95814-2922 Subject: Amendment to the Formal Consultation on the Stockton Deep Water Shipping Channel Dredging and Bank Stabilization Project, Sacramento, Contra Costa, and San Joaquin Counties, California Dear Mr. Ziminske: This letter is in response to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' (Corps) November 8, 2018, request to amend the formal consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on the proposed Stockton Deep Water Shipping Channel (SDWSC) Dredging and Bank Stabilization Project (project), in Sacramento, Contra Costa, and San Joaquin Counties (Service File No. 08FBDT00-2017-F-0098). The Corps proposes to add an additional Dredging Material Placement Site (DMPS) on Tule Island in the SDWSC along the San Joaquin River to replace the unavailable Mandeville Island DMPS. The Corps has determined that the proposed amended project may affect, and is likely to adversely affect the threatened giant garter snake (Thamnophis gigas; GGS). The Corps has also determined that the project may affect, but is not likely to adversely affect the threatened yellow-billed cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus; YBC). This response is in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C.