Air University Quarterly Review: Summer 1948 Volume II, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and 1Rememb Irancees

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution IJnlimiter' The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II REFLECTIONS AND 1REMEMB IRANCEES Veterans of die United States Army Air Forces Reminisce about World War II Edited by William T. Y'Blood, Jacob Neufeld, and Mary Lee Jefferson •9.RCEAIR ueulm PROGRAM 2000 20050429 011 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved I OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of Information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Reflections and Rememberances: Veterans of the US Army Air Forces n/a Reminisce about WWII 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Y'Blood, William T.; Neufeld, Jacob; and Jefferson, Mary Lee, editors. -

Champions Complete

Champions Complete Writing and Design Derek’s Special Thanks Derek Hiemforth To the gamers with whom I first discovered Champions and fell in love with the game: Doug Alger, Andy Broer, Indispensable Contributions Daniel Cole, Dan Connor, Dave Croyle, Guy Pilgrim, and Nelson Rodriguez. Without you guys, my college grades Champions 6th Edition: Aaron Allston and might have been better, but my life would have been much, Steven S. Long much worse. HERO System 6th Edition: Steven S. Long To Gary Denney, Robert Dorf, Chris Goodwin, James HERO System 4th Edition: George MacDonald, Jandebeur, Hugh Neilson, and John Taber, who generously offered insightful commentary and suggestions. Steve Peterson, and Rob Bell And, above all, to my beloved wife Lara, who loves her Original HERO System: George MacDonald and fuzzy hubby unconditionally despite his odd hobby, even Steve Peterson when writing leaves him sleepless or cranky. Layout and Graphic Design HERO System™®. is DOJ, Inc.’s trademark for its roleplaying Ruben Smith-Zempel system. HERO System Copyright © 1984, 1989, 2002, 2009, 2012 by DOJ, Development Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights reserved. Champions, Dark Champions, and all associated characters Jason Walters © 1981-2009 by Cryptic Studios, Inc. All rights reserved. “Champions” and “Dark Champions” are trademarks of Cryptic Cover Art Studios, Inc. “Champions” and “Dark Champions” are used under license from Cryptic Studios, Inc. Sam R. Kennedy Fantasy Hero © 2003, 2010 by DOJ, Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights reserved. Interior Art Star Hero © 2003, 2011 by DOJ, Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights Peter Bergting, Storn Cook, Keith Curtis, reserved. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

O SILENCER Please Continue on Back If Needed!) O TERRIFICS 1/1/18

DARK HORSE IMAGE MARVEL CONT. o AMERICAN GODS Neil Gaiman o ANGELIC o MS MARVEL o ANGEL o BEAUTY o OLD MAN HAWKEYE o BPRD o BLACK SCIENCE o OLD MAN LOGAN o BUFFY o CURSE WORDS o PETER PARKER Spectacular Spider o HARROW COUNTY o DEADLY CLASS o PUNISHER o HELLBOY o DESCENDER o RUNAWAYS DC / VERTIGO COMICS o EAST OF WEST o SHE HULK o ACTION o EXTREMITY o SPIDER-GWEN o AQUAMAN o FIX o SPIDER-MAN o ASTRO CITY o GOD COMPLEX o SPIDER-MAN / DEADPOOL o BANE CONQUEST o HIT GIRL o STAR WARS o BATGIRL o I HATE FAIRYLAND o STAR WARS DARTH VADER o BATGIRL & BIRDS OF PREY o KICK ASS o STAR WARS DOCTOR APHRA o BATMAN o KILL OR BE KILLED o STAR WARS POE DAMERON o BATMAN BEYOND o MONSTRESS o TALES OF SUSPENSE o BATWOMAN o MOONSHINE o THANOS o BOMBSHELLS UNITED o MOTOR CRUSH o UNBEATABLE SQUIRREL GIRL o DAMAGE o OBLIVION SONG o VENOM o DEATHSTROKE o OUTCAST o WEAPON H o DETECTIVE COMICS o PAPER GIRLS o WEAPON X o DOOMSDAY CLOCK o PORT OF EARTH o X-MEN BLUE o FLASH o RAT QUEENS o X-MEN GOLD o FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS o REDLANDS o X-MEN RED o GOTHAM CITY GARAGE o REDNECK VALIANT o GREEN ARROW o ROSE o SHADOWMAN o GREEN LANTERNS o ROYAL CITY o ARMSTRONG o HAL JORDAN GREEN LANTERN CORP o RUMBLE o BLOODSHOT o HARLEY QUINN o SAGA o NINJAK o HELLBLAZER o SNOTGIRL o QUANTUM & WOODY o INJUSTICE 2 o SPAWN o X-O MANOWAR o JUSTICE LEAGUE o VS OTHER o JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA o WALKING DEAD o ADVENTURE TIME o MISTER MIRACLE o WICKED & THE DIVINE o ARCHIE o NEW SUPERMAN & Justice League China o WITCHBLADE o DOCTOR WHO o NIGHTWING o YOUNGBLOOD o GO GO POWER RANGERS o RAGMAN -

Subscription Pamplet New 11 01 18

Add More Titles Below: Vault # CONTINUED... [ ] Aphrodite V [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Auntie Agatha's Wayward Bunnies (6) [ ] James Bond [ ] Bitter Root [ ] Lone Ranger [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Blackbird [ ] Mars Attack [ ] Bully Wars [ ] Miss Fury [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Burnouts [ ] Project SuperPowers 625 N. Moore Ave., [ ] Cemetery Beach (of 7) [ ] Rainbow Brite [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cold Spots (of 5) [ ] Red Sonja Moore OK 73160 [ ] Criminal [ ] Thunderbolt [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Crowded [ ] Turok [ ] Curse Words [ ] Vampirella Dejah Thores [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cyber Force [ ] Vampirella Reanimator Subscription [ ] Dead Rabbit [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Die Comic Pull Sheet [ ] East of West [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Errand Boys (of 5) [ ] Evolution [ ] ___________________________ We offer subscription discounts for [ ] Exorisiters [ ] Freeze [ ] Adventure Time Season 11 [ ] ___________________________ customers who want to reserve that special [ ] Gideon Falls [ ] Avant-Guards (of 12) comic book series with SUPERHERO [ ] Gunning for Hits [ ] Black Badge [ ] ___________________________ BENEFITS: [ ] Hardcore [ ] Bone Parish [ ] Hit-Girl [ ] Buffy Vampire Slayer [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Ice Cream Man [ ] Empty Man Tier 1: 1-15 Monthly ongoing titles: [ ] Infinite Dark [ ] Firefly [ ] ___________________________ 10% Off Cover Price. [ ] Jook Joint (of 5) [ ] Giant Days [ ] Kick-Ass [ ] Go Go Power Rangers [ ] ___________________________ -

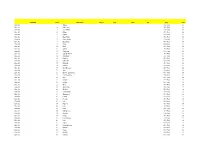

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Mem #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Angela 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 2 Anti-Venom 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 3 Doc Samson 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 4 Attuma 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 5 Bedlam 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 6 Black Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 7 Black Panther 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 8 Black Swan 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 9 Blade 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 10 Blink 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 11 Callisto 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 12 Cannonball 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 13 Captain Universe 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 14 Challenger 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 15 Punisher 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 16 Dark Beast 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 17 Darkhawk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 18 Collector 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 19 Devil Dinosaur 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 20 Ares 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 21 Ego The Living Planet 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 22 Elsa Bloodstone 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 23 Eros 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 24 Fantomex 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 25 Firestar 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 26 Ghost 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 27 Ghost Rider 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 28 Gladiator 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 29 Goblin Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 30 Grandmaster 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 31 Hazmat 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 32 Hercules 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 33 Hulk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 34 Hyperion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 35 Ikari 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 36 Ikaris 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 37 In-Betweener 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 38 Khonshu 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 39 Korvus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 40 Lady Bullseye 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 41 Lash 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 42 Legion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 43 Living Lightning 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 44 Maestro 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 45 Magus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 46 Malekith 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 47 Manifold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 48 Master Mold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 49 Metalhead 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 50 M.O.D.O.K. -

Evolution of the American Airstrike: Psychological Impacts on Drone Operators and WWII Bomber Pilots

Evolution of the American Airstrike: Psychological Impacts on Drone Operators and WWII Bomber Pilots Zach Valk History 489 Capstone Professor: Dr. Patricia Turner Coordinating Professor: Dr. April Bleske-Rechek 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..Page 4 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………..Page 6 U.S Air Force……………….………………………………………………………………………Page 14 Evolution and Understanding of Mental Health of Aviator …………………Page 15 Technological Advances………………………………………………………………………Page 19 Physical Distance…………………………………………………………………………………Page 23 Public Support…………………………………………………………………………………….Page 27 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………..Page 31 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………..Page 34 2 Abstract This research takes a look at the similarities and differences between bomber pilots during World War II and drone operators in the twenty-first century modern military setting. The comparisons will be based on psychological effect of combat on each group as well as the ethical concerns related to their vastly disparate combat environments. This project’s conclusions are based on an analysis of three key aspects: Technological advances, physical distance from the battlefield, and the amount of public support for the given conflict. Public is assessed in part by comparing WWII experiences to other twentieth-century conflicts such as Vietnam and Korea to get a sense of how lack of public support affected pilots before the automation of aircraft. -

Does the United States Need Space-Based Weapons?

After you have read the research report, please give us your frank opinion on the contents. All comments—large or small, complimentary or caustic—will be gratefully appreciated. Mail them to CADRE/AR, Building 1400, 401 Chennault Circle, Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6428. Does the United States Spacy Need Space-Based Weapons? Thank you for your assistance COLLEGE OF AEROSPACE DOCTRINE, RESEARCH, AND EDUCATION AIR UNIVERSITY Does the United States Need Space-Based Weapons? WILLIAM L. SPACY II Major, USAF CADRE Paper Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6610 September 1999 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ISBN 1-58566-070-1 ii CADRE Papers CADRE Papers are occasional publications sponsored by the Airpower Research Institute of Air University’s College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education (CADRE). Dedi- cated to promoting understanding of air and space power theory and application, these studies are published by the Air University Press and broadly distributed to the US Air Force, the Department of Defense and other governmental organiza - tions, leading scholars, selected institutions of higher learning, public policy institutes, and the media. All military members and civilian employees assigned to Air University are invited to contribute unclassified manuscripts. Manuscripts should deal with air and/or space power history, theory, doctrine or strategy, or with joint or combined service matters bearing on the application of air and/or space power. -

Stapleton, Mello OH168

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with MELLO STAPLETON Communications Specialist, Air Force, World War II Air Inspector, Air Force, Korean War 1994 OH 168 1 OH 168 Stapleton, Mello, (1919-2006). Oral History Interview, 1994. User Copy: 2 sound cassettes (ca. 105 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 105 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Mello “Mel” Stapleton, a North Lake, Wisconsin native, discusses his career with the Army Air Force including service with the 11 th Bomb Group, 431 st Bomb Squad in World War II and with the Air Inspector’s Office in Kunsan during the Korean War. Stapleton cites the Depression as a major reason for volunteering in 1939 and mentions using the rifle range at Camp Williams (Wisconsin) during previous training with the Wisconsin National Guard Reserves. He describes the unstructured Army Air Corps basic training he received at Chanute Field (Illinois), being rejected from pilot school due to having astigmatism, and his first duties dealing with primitive communications equipment in the Signal Corps. Shipped to Hawaii, Stapleton tells of his ship being quarantined for measles and describes the five months spent on board. Stationed at Hickam Field (Hawaii), he speaks about living in tents while the barracks was being built, his duties, available recreation, and a lack of rivalry between service branches. He recalls in detail the attack on Pearl Harbor. At an all-night beach party the night before, he talks about the Hickam Field’s dining hall being destroyed, everyone running to get guns, shooting at Japanese planes, the devastation of the barracks, and the loss of most airplanes on the islands. -

NEW THIS WEEK from DC... Action Comics #1000 Batman #45

NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Action Comics #1000 Batman #45 Superman #45 Justice League #43 Super Sons #15 Brave & the Bold Batman & Wonder Woman #3 (of 6) Batman Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II #6 (of 6) Mister Miracle #8 (of 12) Nightwing #43 Batman Creature of the Night #3 (of 4) Green Lanterns #45 Aquaman #35 Batman Sins of the Father #3 (of 6) Damage #4 Batwoman #14 Action Comics 80 Years of Superman Poster Harley Quinn #42 Deadman #6 (of 6) Deathbed #3 (of 6) Bombshells United #16 Cave Carson Has an Interstellar Eye #2 Future Quest Presents #9 Injustice 2 #24 Deathstroke Vol. 4 GN Red Hood & the Outlaws Vol. 3 GN Action #1000 Superman T/S LG XL XXL NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL ... Amazing Spider-Man #799 Weapon H #2 Leg Infinity Countdown #2 (of 5) Avengers #689 Daredevil #601 X-Men Gold #26 Black Panther #172 Star Wars Poe Dameron #26 True Believers Rebirth of Thanos #1 Venomized #3 (of 5) Incredible Hulk #715 Cable #156 Iron Fist #80 Amazing Spider-Man #795 B&W 3rd PTG Amazing Spider-Man Renew Your Vows #18 Deadpool #300 by Koblish Poster Tales of Suspense #104 (of 5) Ms Marvel Weapon X #16 Punisher Platoon GN Phoenix Resurrection Return Jean Grey GN Pocket Pop Agents of Shield Ghost Rider Vin Fig Runaways by Rainbow Rowell Vol. 1 GN True Believers Venom vs Spider-Man #1 2nd PTG True Believers Infinity Incoming #1 NEW FROM IMAGE ... Kick-Ass #3 Lazarus #27 Moonshine #9 Skyward #1 Curse Words #13 Royal City Vol. -

32, Air Power, Armies, and the War in the West, 1940., R.J. Overy, 1989

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #32 Air Power, Armies, and the War in the West, 1940 R.J. Overy, 1989 It is now almost fifty years since German armies routed British and French forces on the northern plains of France. It was a victory almost unique in twentieth-century warfare in its speed and decisiveness. So rapid and well planned was the German advance that it was not difficult to argue that this was just the campaign for which Hitler had long been preparing. German victory strengthened the view that the Western Allies stood before him weakened by years of military neglect and political feebleness. Since the war, this view has become embedded in popular wisdom. There is a strong consensus that the Western powers were militarily unprepared, much weaker than the enemy they faced, and that German success rested on exploitation of the new air and tank weapons. This new technology was integrated in the Blitzkrieg formula, which cruelly exposed the poor planning, strategic bankruptcy, and low morale of Germany’s enemies. The core of German success, so the argument goes, was the overwhelming air power that Germany brought to bear on the conflict. At least one historian of the campaign has concluded that it was “the Luftwaffe’s supremacy in the air which constituted a decisive factor.”1 Though there would be little point in denying that the air force did constitute an important element in Germany’s success in May and June 1940, there remain nonetheless a great many questions that historians can still ask about the role of air power in the campaign. -

KOTORII Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain PUBLIC ACCESS AVAILABLE> VERBAL visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition COMMANDS ENABLED> READY FOR INQUIRY> that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, Introduction........................................................................................3........................................................................................3 or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or Installation....................................................................................................................................................................................3 convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Default Controls ................................................................................................................................................................4 Main Menu ........................................................................................6 Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of