Deciphering Arrernte Archives: the Intermingling of Textual and Living Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction The subjects of ethnographies, it should never be forgotten, are always more interesting than their authors. —R.J. Smith (1990) In the autumn of 2016, I met with two Arrernte men, Shaun and Martin, who had flown from the remote township of Alice Springs, in the center of Australia, to meet with me at my office in the Melbourne Museum. The purpose of their visit was to discuss the potential return of sacred ritual objects to central Australia. I had known both of these men for a number of years, but Shaun and I had a particularly long association. We had worked together at an Aboriginal youth service in Alice Springs over a decade earlier, and as we struck up a friendship he had taken me on a hunting trip for kangaroo on his homelands at Arewengkwerte. Our paths had diverged over the years, but we had once again come together as professionals in the Indigenous museum and heritage sector. Shaun now worked as a researcher at the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs, and I had returned to my home city of Melbourne where I worked in the museum’s Indigenous Cultures Department. Over a number of days, Shaun and I looked into the history of these sacred objects, with Shaun’s uncle Martin providing prudent counsel, pon- dering how they came to be in the possession of a museum 2,300 kilometers from their place of origin. Our research and discussions meandered along a path that eventually led us back to questions about the degree of agency exhibited by central Australian men in the production of collections such as this. -

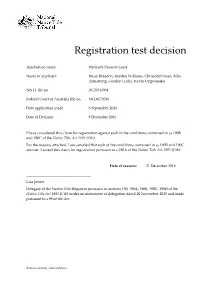

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Henbury Pastoral Lease Name of applicant Bruce Breadon, Baydon Williams, Christobel Swan, Felix Armstrong, Gordon Lucky, Kevin Ungwanaka NNTT file no. DC2016/004 Federal Court of Australia file no. NTD47/2016 Date application made 6 September 2016 Date of Decision 9 December 2016 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Date of reasons: 21 December 2016 ___________________________________ Lisa Jowett Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) under an instrument of delegation dated 20 November 2015 and made pursuant to s 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the Henbury Pastoral Lease native title determination application (NTD44/2016) to the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) on 1 September 2016 pursuant to s 63 of the Act1. This has triggered the Registrar’s duty to consider the claim made in the application for registration in accordance with s 190A: see subsection 190A(1). [2] Sections 190A(1A), (6), (6A) and (6B) set out the decisions available to the Registrar under s 190A. Subsection 190A(1A) provides for exemption from the registration test for certain amended applications and s 190A(6A) provides that the Registrar must accept a claim (in an amended application) when it meets certain conditions. -

Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2014. Edited by Helaine Selin. Springer Netherlands, preprint. Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians Duane W. Hamacher Nura Gili Centre for Indigenous Programs, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Email: [email protected] Of the hundreds of distinct Aboriginal cultures of Australia, many have oral traditions rich in descriptions and explanations of comets, meteors, meteorites, airbursts, impact events, and impact craters. These views generally attribute these phenomena to spirits, death, and bad omens. There are also many traditions that describe the formation of meteorite craters as well as impact events that are not known to Western science. Comets Bright comets appear in the sky roughly once every five years. These celestial visitors were commonly seen as harbingers of death and disease by Aboriginal cultures of Australia. In an ordered and predictable cosmos, rare transient events were typically viewed negatively – a view shared by most cultures of the world (Hamacher & Norris, 2011). In some cases, the appearance of a comet would coincide with a battle, a disease outbreak, or a drought. The comet was then seen as the cause and attributed to the deeds of evil spirits. The Tanganekald people of South Australia (SA) believed comets were omens of sickness and death and were met with great fear. The Gunditjmara people of western Victoria (VIC) similarly believed the comet to be an omen that many people would die. In communities near Townsville, Queensland (QLD), comets represented the spirits of the dead returning home. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

FIGHTING OVER COUNTRY: Anthropological Perspectives

FIGHTING OVER COUNTRY: Anthropological Perspectives Edited by D.E. Smith and J. Finlayson Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research The Australian National University, Canberra Research Monograph No. 12 1997 First published in Australia 1997. Printed by Instant Colour Press, Canberra, Australia. © Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University. This book is copyright Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia. National Library of Australia. Cataloguing-in-publication entry. Fighting over country: anthropological perspectives ISBN 07315 2561 2. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Land tenure. 2. Native title - Australia. 3. Torres Strait Islanders - Land tenure. 4. Land use - Australia. I. Finlayson, Julie, n. Smith, Diane (Diane Evelyn). ID. The Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. (Series: Research monograph (The Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research); no. 12). 306.320899915 Acknowledgments A number of people assisted in the organisation and conduct of the workshop Fighting Over Country: Anthropological Perspectives held in Canberra in late September 1996. The workshop was the latest in a series sponsored by the Australian Anthropological Society focusing on land rights and native title issues. Diane Smith, Julie Finlayson, Francesca Merlan, Mary Edmunds and David Trigger formed the organising committee, and ongoing administrative support was provided by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR). The Native Titles Research Unit of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) provided modest but very helpful financial assistance towards catering for the workshop. -

Presentation Tile

Authentic and engaging artist-led Education Programs with Thomas Readett Ngarrindjeri, Arrernte peoples 1 Acknowledgement 2 Warm up: Round Robin 3 4 See image caption from slide 2. installation view: TARNANTHI featuring Mumu by Pepai Jangala Carroll, 2015, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; photo: Saul Steed. 5 What is TARNANTHI? TARNANTHI is a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists from across the country to share important stories through contemporary art. TARNANTHI is a national event held annually by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Although TARNANTHI at AGSA is annual, biannually TARNANTHI turns into a city-wide festival and hosts hundreds of artists across multiple venues across Adelaide. On the year that the festival isn’t on, TARNANTHI focuses on only one feature artist or artist collective at AGSA. Jimmy Donegan, born 1940, Roma Young, born 1952, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, 1940–2018, Brenton Ken, born 1944, Witjiti George, born 1938, Sammy Dodd, born 1946, Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Freddy Ken, born 1951, Naomi Kantjuriny, born 1944, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, born 1940, Willy Kaika Burton, born 1941, Rupert Jack, born 1951, Adrian Intjalki, born 1943, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, c.1930–2016, Arnie Frank, born 1960, Stanley Douglas, born 1944, Maureen Douglas, born 1966, Willy Muntjantji Martin, born 1950, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, born 1940, Noel Burton, born 1994, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, 1937–2017, -

Commonwealth of Australia

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of The Charles Darwin University with permission from the author(s). Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander THESAURUS First edition by Heather Moorcroft and Alana Garwood 1996 Acknowledgements ATSILIRN conference delegates for the 1st and 2nd conferences. Alex Byrne, Melissa Jackson, Helen Flanders, Ronald Briggs, Julie Day, Angela Sloan, Cathy Frankland, Andrew Wilson, Loris Williams, Alan Barnes, Jeremy Hodes, Nancy Sailor, Sandra Henderson, Lenore Kennedy, Vera Dunn, Julia Trainor, Rob Curry, Martin Flynn, Dave Thomas, Geraldine Triffitt, Bill Perrett, Michael Christie, Robyn Williams, Sue Stanton, Terry Kessaris, Fay Corbett, Felicity Williams, Michael Cooke, Ely White, Ken Stagg, Pat Torres, Gloria Munkford, Marcia Langton, Joanna Sassoon, Michael Loos, Meryl Cracknell, Maggie Travers, Jacklyn Miller, Andrea McKey, Lynn Shirley, Xalid Abd-ul-Wahid, Pat Brady, Sau Foster, Barbara Lewancamp, Geoff Shepardson, Colleen Pyne, Giles Martin, Herbert Compton Preface Over the past months I have received many queries like "When will the thesaurus be available", or "When can I use it". Well here it is. At last the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Thesaurus, is ready. However, although this edition is ready, I foresee that there will be a need for another and another, because language is fluid and will change over time. As one of the compilers of the thesaurus I am glad it is finally completed and available for use. -

Reflections on the Preparation and Delivery of Carl Strehlow's Heritage

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 18 Archival returns: Central Australia and beyond ed. by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green & Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, pp. 47–63 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp18 3 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24877 Reflections on the preparation and delivery of Carl Strehlow’s heritage dictionary (1909) to the Western Aranda people Anna Kenny Australian National University Abstract This chapter reflects on the predicaments encountered while bringing ethnographic and linguistic archival materials, and in particular an Aranda, German, Loritja [Luritja], and Dieri dictionary manuscript compiled by Carl Strehlow and with more than 7600 entries, into the public domain. This manuscript, as well as other unique documents held at the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs and elsewhere in Australia, is surrounded by competing views about ownership and control. In this case study I discuss my research and work with Western Aranda people concerning the transcription and translation into English of the dictionary manuscript. I also discuss the immense difficulties I faced in seeing the dictionary through to final publication. I encountered vested interests in this ethno-linguistic treasure that I had not been aware of and ownership claims that I had not taken into account. They arose from diverse quarters – from academia, from individuals in the Lutheran church, from Indigenous organisations, and from the Northern Territory Government. One such intervention almost derailed the dictionary work by actions that forced the suspension of the project for over 12 months. In this chapter I track the complex history of this manuscript, canvas the views of various stakeholders, and detail interpretations and reactions of Aranda people to the issues involved. -

Endangered by Desire T.G.H. Strehlow and The

ENDANGERED BY DESIRE T.G.H. STREHLOW AND THE INEXPLICABLE VAGARIES OF PRIVATE PASSION By S. j. Hersey THESIS Presented as a thesis for the fulfilment of the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) School of Communication Arts, the University of Western Sydney, Werrington Campus. 2006 The author declares that the research reported in this thesis has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other university or institution. Information acquired from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is provided. Shane jeffereys Hersey ………………………………………………………………………… University of Western Sydney Abstract ENDANGERED BY DESIRE T.G.H. STREHLOW AND THE INEXPLICABLE VAGARIES OF PRIVATE PASSION By Shane Hersey Supervisor: Associate Professor Hart Cohen Co-supervisor Dr Maria Angel School of Communication Arts This thesis is about the depth of colonisation through translation. I develop an analytic framework that explores colonisation and translation using the trope of romantic love and an experimental textual construction incorporating translation and historical reconstruction. Utilising both the first and the final drafts of “Chapter X, Songs of Human Beauty and Love-charms” in Songs of Central Australia, by T. Strehlow, I show how that text, written over thirty years and comprised of nine drafts, can be described as a translation mediated by the colonising syntax and grammar. My interest lies in developing a novel textual technique to attempt to illustrate this problem so as to allow an insight into the perspective of a colonised person. This has involved a re-examination of translation as something other than a transtemporal structure predicated on direct equivalence, understanding it instead as something that fictionalises and reinvents the language that it purports to represent. -

Ampe-Kenhe Ahelhe

Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe COMMUNITY REPORT 2018 A Photography by Children’s Ground staff and families © All photographs, filming and recordings of Arrernte people and country is owned by Arrernte people and used by Children’s Ground with their permission. Painting ‘The Children’s Ground’ by Rod Moss, 2018 Contents Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe is the Arrernte translation for Children’s Ground. This is the name we use for 03 From our Director: MK Turner Children’s Ground in Central Australia. Mparntwe is the Arrernte word for the area in and around Alice Springs. 04 Ingkerrekele Arntarnte-areme | Everyone Being Responsible (Governance) 05 Anwerne-kenhe Angkentye, Iterrentye | Our Principles 07 From our Chairperson: William Tilmouth 08 From our Directors: The Story So Far 10 Ampe Mape Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe | Children’s Ground Children 2018 12 Ampe Akweke Mape-kenhe Ayeye | Children’s Stories 18 Akaltye-irreme Unte Mwerre Anetyeke | Learning and Wellbeing 20 Anwerne Ingkerreke Apurte Urrkapeme | Working Side by Side 22 Arrernte-kenhe Angkentye | Arrernte Curriculum 23–29 Akaltye-irreme Apmerele | Learning on Country 30 Tyerrtye Mwerre Anetyeke | Health and Wellbeing 32 Mwerrentye Warrke Irretyeke | Economic Development and Wellbeing 36 Arne Mpwaretyeke, Mwantyele Antirrkwetyke | Creative Development and Wellbeing 42 Tyerrtye Areye Mwerre Anetyeke | Community Development and Wellbeing 44 Ayeye Anwerne-kenhe ileme | Sharing Our Story 46 Anwerne ingkerreke Apurte Irretyeke | Reconciliation Week 2018: We All Get Together 50 Ampe Anwernekenhe Rlterrke Ingkerre Atnyenetyeke | Keeping All Our Children Strong 51 Kele Mwerre | Thank you 52 Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe Staff 2018 1 “Anwerne Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe-nge warrke mwerre anthurre mpwareke year- nhengenge. -

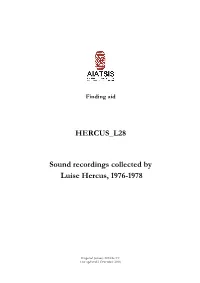

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Luise Hercus 1976-1978

Finding aid HERCUS_L28 Sound recordings collected by Luise Hercus, 1976-1978 Prepared January 2012 by CC Last updated 2 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from Luise Hercus as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1976-1978 Extent: 43 sound tape reels (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, mono ; 5 in. Production history These recordings were collected by Luise Hercus in between July 1976 and February 1978 funded by an AIAS (now AIATSIS) grant to study languages collected by interviewees in North East South Australia and Wilcannia, New South Wales. The interviewees are Alice Oldfield, Mona (Merna) Merrick, Elsie Bowman, Ernie Ellis, Brian Marks, Arthur Warren, Ben Murray, Maudie Reese (nee Lennie) and George Macumba who provided the South Australian languages of Arabana, Kuyani, Wangkangurru and Diyari during which references were made to and influences noted from Central Desert languages. Gertie Johnson and Elsie Jones provided Paakantyi material language from NSW; and Jack Long provided Madhi Madhi, Nari Nari, Dadi Dadi language material from NSW and Victoria. -

Meteoritics and Cosmology Among the Aboriginal Cultures of Central Australia

Journal of Cosmology, Volume 13, pp. 3743-3753 (2011) Meteoritics and Cosmology Among the Aboriginal Cultures of Central Australia Duane W. Hamacher Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia [email protected] Abstract The night sky played an important role in the social structure, oral traditions, and cosmology of the Arrernte and Luritja Aboriginal cultures of Central Australia. A component of this cosmology relates to meteors, meteorites, and impact craters. This paper discusses the role of meteoritic phenomena in Arrernte and Luritja cosmology, showing not only that these groups incorporated this phenomenon in their cultural traditions, but that their oral traditions regarding the relationship between meteors, meteorites and impact structures suggests the Arrernte and Luritja understood that they are directly related. Note to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Readers This paper contains the names of, and references to, people that have passed away and references the book “Nomads of the Australian Desert” by Charles P. Mountford (1976), which was banned for sale in the Northern Territory as it contained secret information about the Pitjantjatjara. No information from the Pitjantjatjara in that book is contained in this paper. 1.0 Introduction Creation stories are the core of cosmological knowledge of cultures around the globe. To most groups of people, the origins of the land, sea, sky, flora, fauna, and people are formed by various mechanisms from deities or beings at some point in the distant past. Among the more than 400 Aboriginal language groups of Australia (Walsh, 1991) that have inhabited the continent for at least 45,000 years (O’Connell & Allen, 2004) thread strong oral traditions that describe the origins of the world, the people, and the laws and social structure on which the community is founded, commonly referred to as “The Dreaming” (Dean, 1996).