Arxiv:2108.13431V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 30 Aug 2021 Vived Dynamical Effects and Remain Gravitationally Bound Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3257/arxiv-2012-09981v1-astro-ph-sr-17-dec-2020-2-o-73257.webp)

Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O

Contrib. Astron. Obs. Skalnat´ePleso XX, 1 { 20, (2020) DOI: to be assigned later Flare stars in nearby Galactic open clusters based on TESS data Olga Maryeva1;2, Kamil Bicz3, Caiyun Xia4, Martina Baratella5, Patrik Cechvalaˇ 6 and Krisztian Vida7 1 Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondˇrejov,The Czech Republic(E-mail: [email protected]) 2 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetsky pr. 13, 119234, Moscow, Russia 3 Astronomical Institute, University of Wroc law, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc law, Poland 4 Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotl´aˇrsk´a2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Galileo Galilei, Vicolo Osservatorio 3, 35122, Padova, Italy, (E-mail: [email protected]) 6 Department of Astronomy, Physics of the Earth and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynsk´adolina F-2, 842 48 Bratislava, Slovakia 7 Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, H-1121 Budapest, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os´ut15-17, Hungary Received: September ??, 2020; Accepted: ????????? ??, 2020 Abstract. The study is devoted to search for flare stars among confirmed members of Galactic open clusters using high-cadence photometry from TESS mission. We analyzed 957 high-cadence light curves of members from 136 open clusters. As a result, 56 flare stars were found, among them 8 hot B-A type ob- jects. Of all flares, 63 % were detected in sample of cool stars (Teff < 5000 K), and 29 % { in stars of spectral type G, while 23 % in K-type stars and ap- proximately 34% of all detected flares are in M-type stars. -

Messier Plus Marathon Text

Messier Plus Marathon Object List by Wally Brown & Bob Buckner with additional objects by Mike Roos Object Data - Saguaro Astronomy Club Score is most numbered objects in a single night. Tiebreaker is count of un-numbered objects Observer Name Date Address Marathon Obects __________ Tiebreaker Objects ________ SEQ OBJECT TYPE CON R.A. DEC. RISE TRANSIT SET MAG SIZE NOTES TIME M 53 GLOCL COM 1312.9 +1810 7:21 14:17 21:12 7.7 13.0' NGC 5024, !B,vC,iR,vvmbM,st 12.. NGC 5272, !!,eB,vL,vsmbM,st 11.., Lord Rosse-sev dark 1 M 3 GLOCL CVN 1342.2 +2822 7:11 14:46 22:20 6.3 18.0' marks within 5' of center 2 M 5 GLOCL SER 1518.5 +0205 10:17 16:22 22:27 5.7 23.0' NGC 5904, !!,vB,L,eCM,eRi, st mags 11...;superb cluster M 94 GALXY CVN 1250.9 +4107 5:12 13:55 22:37 8.1 14.4'x12.1' NGC 4736, vB,L,iR,vsvmbM,BN,r NGC 6121, Cl,8 or 10 B* in line,rrr, Look for central bar M 4 GLOCL SCO 1623.6 -2631 12:56 17:27 21:58 5.4 36.0' structure M 80 GLOCL SCO 1617.0 -2258 12:36 17:21 22:06 7.3 10.0' NGC 6093, st 14..., Extremely rich and compressed M 62 GLOCL OPH 1701.2 -3006 13:49 18:05 22:21 6.4 15.0' NGC 6266, vB,L,gmbM,rrr, Asymmetrical M 19 GLOCL OPH 1702.6 -2615 13:34 18:06 22:38 6.8 17.0' NGC 6273, vB,L,R,vCM,rrr, One of the most oblate GC 3 M 107 GLOCL OPH 1632.5 -1303 12:17 17:36 22:55 7.8 13.0' NGC 6171, L,vRi,vmC,R,rrr, H VI 40 M 106 GALXY CVN 1218.9 +4718 3:46 13:23 22:59 8.3 18.6'x7.2' NGC 4258, !,vB,vL,vmE0,sbMBN, H V 43 M 63 GALXY CVN 1315.8 +4201 5:31 14:19 23:08 8.5 12.6'x7.2' NGC 5055, BN, vsvB stell. -

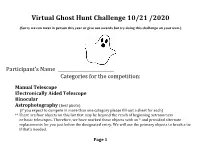

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Open Clusters in Gaia

Sede Amministrativa: Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “G. Galilei” Corso di Dottorato di Ricerca in Astronomia Ciclo XXX OPEN CLUSTERS IN GAIA ERA Coordinatore: Ch.mo Prof. Giampaolo Piotto Supervisore: Dr.ssa Antonella Vallenari Dottorando: Francesco Pensabene i Abstract Context. Open clusters (OCs) are optimal tracers of the Milky Way disc. They are observed at every distance from the Galactic center and their ages cover the entire lifespan of the disc. The actual OC census contain more than 3000 objects, but suffers of incom- pleteness out of the solar neighborhood and of large inhomogeneity in the parameter deter- minations present in literature. Both these aspects will be improved by the on-going space mission Gaia . In the next years Gaia will produce the most precise three-dimensional map of the Milky Way by surveying other than 1 billion of stars. For those stars Gaia will provide extremely precise measure- ment of proper motions, parallaxes and brightness. Aims. In this framework we plan to take advantage of the first Gaia data release, while preparing for the coming ones, to: i) move the first steps towards building a homogeneous data base of OCs with the high quality Gaia astrometry and photometry; ii) build, improve and test tools for the analysis of large sample of OCs; iii) use the OCs to explore the prop- erties of the disc in the solar neighborhood. Methods and Data. Using ESO archive data, we analyze the photometry and derive physical parameters, comparing data with synthetic populations and luminosity functions, of three clusters namely NGC 2225, NGC 6134 and NGC 2243. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

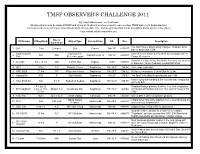

The 2011 Observers Challenge List

TMSP OBSERVER'S CHALLENGE 2011 By Kreig McBride and Tom Masterson All observations must be made at TMSP and 25 out of 30 objects must be viewed to earn a unique TMSP Observer's Award lapel pin. You must create a record of your observations which include date, time, instruments used and a brief description and/or sketch of the object. Your records will be returned to you. Size or ID Number V Magnitude Object Type Constellation RA Dec Description Separation The Sun! View 2 days noting changes. H-alpha, white 1 Sol -28m ½ degree Star Cancer 08h 39' +27d 07' light or projection is OK North Galactic Astronomical Catch this one before it sets. Next to the double star 31 2 N/A N/A Coma Berenices 12h 51' +27d 07' Pole Reference point Comae Berenices Omicron-2 a wide 4.9m, 9m double lies close by as does 3 U Cygni 5.9 – 12.1m N/A Carbon Star Cygnus 19.6h +47d 54' 6” diameter, 12.6m Planetary nebula NGC6884 4 M22 5.1m 7.8' Globular Cluster Sagittarius 18h 36.4' -23d 54' Rich, large and bright 5 NGC 6629 11.3m 15” Planetary Nebula Sagittarius 18h 25.7' -23d 12' Stellar at low powers. Central Star is 12.8m 6 Barnard 86 N/A 5' Dark Nebula Sagittarius 18h 03' -27d 53' “Ink Spot” Imbedded in spectacular star field Faint 1' glow surrounding 9.5m star w/a faint companion 7 NGC 6589-90 N/A 5' x 3' Reflection Nebula Sagittarius 18h 16.9'' -19d 47' 25” to its SW A 3.2m, B Reddish/Orange primary, B white, C is 10m companion 8 ETA Sagittarii 3.6m, C 10m, AB pair 3.6” Quadruple Star Sagittarius 18h 17.6' -36d 46' 93” distant at PA303d and D is 13m star 33” -

00E the Construction of the Universe Symphony

The basic construction of the Universe Symphony. There are 30 asterisms (Suites) in the Universe Symphony. I divided the asterisms into 15 groups. The asterisms in the same group, lay close to each other. Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!Objects nearby 01 The W!!!Cassiopeia!!Segin !!!!!!!Ruchbah !!!!!!!Marj !!!!!!!Schedar !!!!!!!Caph !!!!!!!!!Sailboat Cluster !!!!!!!!!Gamma Cassiopeia Nebula !!!!!!!!!NGC 129 !!!!!!!!!M 103 !!!!!!!!!NGC 637 !!!!!!!!!NGC 654 !!!!!!!!!NGC 659 !!!!!!!!!PacMan Nebula !!!!!!!!!Owl Cluster !!!!!!!!!NGC 663 Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!!Objects nearby 02 Northern Fly!!Aries!!!41 Arietis !!!!!!!39 Arietis!!! !!!!!!!35 Arietis !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1056 02 Whale’s Head!!Cetus!! ! Menkar !!!!!!!Lambda Ceti! !!!!!!!Mu Ceti !!!!!!!Xi2 Ceti !!!!!!!Kaffalijidhma !!!!!!!!!!IC 302 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 990 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1024 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1026 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1070 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1085 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1107 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1137 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1143 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1144 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1153 Asterisms!! in Constellation Stars!!Objects nearby 03 Hyades!!!Taurus! Aldebaran !!!!!! Theta 2 Tauri !!!!!! Gamma Tauri !!!!!! Delta 1 Tauri !!!!!! Epsilon Tauri !!!!!!!!!Struve’s Lost Nebula !!!!!!!!!Hind’s Variable Nebula !!!!!!!!!IC 374 03 Kids!!!Auriga! Almaaz !!!!!! Hoedus II !!!!!! Hoedus I !!!!!!!!!The Kite Cluster !!!!!!!!!IC 397 03 Pleiades!! ! Taurus! Pleione (Seven Sisters)!! ! ! Atlas !!!!!! Alcyone !!!!!! Merope !!!!!! Electra !!!!!! Celaeno !!!!!! Taygeta !!!!!! Asterope !!!!!! Maia !!!!!!!!!Maia Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope -

A. L. Observing Programs Object Duplications

A. L. OBSERVING PROGRAMS OBJECT DUPLICATIONS Compiled by Bill Warren Note: This report is limited to the following A. L. observing programs: Arp Peculiar Galaxies; Binocular Messier; Caldwell; Deep Sky Binocular; Galaxy Groups & Clusters; Globular Cluster; Herschel 400; Herschel II; Lunar; Messier; Open Cluster; Planetary Nebula; Universe Sampler; and Urban. It does not include the other A. L. observing programs, none of which contain duplicated objects. Like the A. L. itself, I’m using constellation names, not genitives (e.g., Orion, not Orionis) with double stars as an aid for beginners who might be referencing this. -Bill Warren Considerable duplication exists among the various A.L. observing programs. In fact, no less than 228 objects (8 lunar, 14 double stars and 206 deep-sky) appear in more than one program. For example, M42 is on the lists of the Messier, Binocular Messier, Universe Sampler and Urban Program. Duplication is important because, with certain exceptions noted below, if you observe an object once you can use that same observation in other A. L. programs in which that object appears. Of the 110 Messiers, 102 of them are also on the Binocular Messier list (18x50 version). To qualify for a Binocular Messier pin, you need only to find any 70 of them. Of course, they are duplicates only when you observe them in binocs; otherwise, they must be observed separately. Among its 100 targets, the Urban Program contains 41 Messiers, 14 Double Stars and 27 other deep-sky objects that appear on other lists. However, they are duplicates only if they are observed under light-polluted conditions; otherwise, they must be observed separately. -

Characterising Open Clusters in the Solar Neighbourhood with the Tycho-Gaia Astrometric Solution? T

A&A 615, A49 (2018) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201731251 & © ESO 2018 Astrophysics Characterising open clusters in the solar neighbourhood with the Tycho-Gaia Astrometric Solution? T. Cantat-Gaudin1, A. Vallenari1, R. Sordo1, F. Pensabene1,2, A. Krone-Martins3, A. Moitinho3, C. Jordi4, L. Casamiquela4, L. Balaguer-Núnez4, C. Soubiran5, and N. Brouillet5 1 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università di Padova, vicolo Osservatorio 3, 35122 Padova, Italy 3 SIM, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Ed. C8, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 4 Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 5 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, UMR 5804, 33615 Pessac, France Received 26 May 2017 / Accepted 29 January 2018 ABSTRACT Context. The Tycho-Gaia Astrometric Solution (TGAS) subset of the first Gaia catalogue contains an unprecedented sample of proper motions and parallaxes for two million stars brighter than G 12 mag. Aims. We take advantage of the full astrometric solution available∼ for those stars to identify the members of known open clusters and compute mean cluster parameters using either TGAS or the fourth U.S. Naval Observatory CCD Astrograph Catalog (UCAC4) proper motions, and TGAS parallaxes. Methods. We apply an unsupervised membership assignment procedure to select high probability cluster members, we use a Bayesian/Markov Chain Monte Carlo technique to fit stellar isochrones to the observed 2MASS JHKS magnitudes of the member stars and derive cluster parameters (age, metallicity, extinction, distance modulus), and we combine TGAS data with spectroscopic radial velocities to compute full Galactic orbits. -

2015 in Living Color

THE TEXAS STAR PARTY 2015 TELESCOPE OBSERVING CLUB BY JOHN WAGONER TEXAS ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF DALLAS RULES AND REGULATIONS Welcome to the Texas Star Party's Telescope Observing Club. The purpose of this club is not to test your observing skills by throwing the toughest objects at you that are hard to see under any conditions, but to give you an opportunity to observe 25 showcase objects under the ideal conditions of these pristine West Texas skies, thus displaying them to their best advantage. The regular observing program is “In Living Color”. These are colorful objects consisting of single, double, & multiple stars and planetary nebula. Note any color you detect in your observing notes. You need to observe 25 objects of the 30 available to get your pin, but if you are using a smaller scope and have a little trouble with some of the objects, just mark it as “tried” and move on, and you will get credit for the object. If you detect a hint of color, please note this in your log. We are also bringing back “I Have No Idea Where I Am” from 2013. This is a list of 29 objects. Only 25 objects need be observed. That's it. Any size telescope can be used. All observations must be made at the Texas Star Party to qualify. All objects are within range of small (6”) to medium sized (10”) telescopes, and are available for observation between 9:00PM and 5:00AM any time during the TSP. Each person completing this list will receive an official Texas Star Party Telescope Observing Club lapel pin. -

AL Urban Observing Program

AL Urban Observing Program Introduction The purpose of the Urban Program is to bring amateur astronomy back to the cities, back to those areas that are affected by heavy light pollution. Amateur astronomy used to be called "backyard astronomy". This was in the days when light pollution was not a problem, and you could pursue your hobby from the comfort of your backyard. But as cities grew, so did light pollution, and the amateur astronomer was forced to drive further and further out into the country to escape that light pollution. It is not uncommon today for a city dweller to drive 100 miles to enjoy his/her hobby. But many people do not have the time or the resources to drive great distances to achieve dark skies. That is the reason for the creation of this program, to allow those who want to enjoy the wonders of the heavens in the comfort of their own neighborhoods to do so, and to maximize the observing experience despite the presence of heavy light pollution. The list of Urban Program objects consists of 87 deep-sky objects, 12 double stars and 1 variable star. The objects on this list have been observed from the East Coast to Middle America to the West Coast, and from major metropolitan areas like Miami, Baltimore, Dallas, Houston, and Los Angeles. Sky limiting magnitudes went from a high of 4, down to 2, to a "Geez" on one particularly bad evening. Instruments ranged from a six-inch reflector to a ten-inch SCT. There is a world of objects out there that can be enjoyed under even poor skies, and it only takes a small to medium sized telescope to enjoy them. -

RASC Finest NGC Observing Program Checklist

RASC Finest NGC Observing Program Checklist Use this checklist to monitor your progress. Version 1.0a. Edited on 9 June 2021. Record your detailed observations on the provided observing forms or your own log sheets. Sketching is optional but highly encouraged. The "+" column denotes special combination objects. E.g. FNGC # 26 is for NGC 1973 with 1975 and 1977. Number NGC + Alternate ID Con Cls RA 2000 Decl 2000 Mag Size Rating Done The Autumn Sky 1 NGC 7009 Saturn Nebula Aqr PN 21h04m10.9s -11°21'48" 8.3 28" !! q 2 NGC 7293 Helix Aqr PN 22h29m38.5s -20°50'14" 6.3 16.0' !! q 3 NGC 7331 Deer Lick Group Peg Gal 22h37m04.3s +34°24'59" 10.2 9.1'x 3.4' !! q 4 NGC 7635 Bubble Nebula Cas EN 23h20m43.0s +61°12'31" 11 16.0'x 9.0' q 5 NGC 7789 OCL 269 Cas OC 23h57m24.0s +56°42'30" 7.5 25.0' !! q 6 NGC 185 MCG 8-2-10 Cas Gal 00h38m57.9s +48°20'15" 10.2 10.7'x 8.9' q 7 NGC 281 PacMan Nebula Cas EN 00h53m00.0s +56°37'00" 7.4 30.0' !! q 8 NGC 457 ET Cluster Cas OC 01h19m35.0s +58°17'12" 5.1 20.0' q 9 NGC 663 Collinder 20 Cas OC 01h46m09.0s +61°14'06" 6.4 14.0' q 10 IC 289 PN G138.8+02.8 Cas PN 03h10m19.3s +61°19'01" 12 45" q 11 NGC 7662 Blue Snowball And PN 23h25m54.0s +42°32'05" 8.6 17" !! q 12 NGC 891 Silver Needle And Gal 02h22m33.6s +42°20'46" 10.9 11.7'x 2.3' !! q 13 NGC 253 Sculptor Galaxy Scl Gal 00h47m33.1s -25°17'20" 7.9 28.2'x 5.5' !! q 14 NGC 772 Arp 78 Ari Gal 01h59m20.0s +19°00'28" 10.6 5.9'x 3.2' q 15 NGC 246 Skull Nebula Cet PN 00h47m03.3s -11°52'19" 10.4 4.0' q 16 NGC 936 MCG 0-7-17 Cet Gal 02h27m37.5s -01°09'20" 11.2 4.5'x 3.4' q 17