Red Tape Or Red Herring?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

Atlas Network Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80k2f0h No online items Register of the Atlas Network records Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015, 2019 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Atlas Network 2015C50 1 records Title: Atlas Network records Date (inclusive): 1946-2013 Collection Number: 2015C50 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: In English and Spanish Physical Description: 319 ms. boxes, 1 oversize box(160.5 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, memoranda, conference papers and other conference materials, fundraising and grant award records, other financial records, and printed matter relating to international promotion of free market economic policies. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 2015. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Atlas Network records, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Historical Note The Atlas Network was founded in Fairfax, Virginia, as the Atlas Economic Research Foundation, in 1981. Its founder, Sir Antony Fisher (1915-1988), had already created the Institute of Economic Affairs in his native Great Britain and the Fraser Institute in Canada. The purpose of these organizations was promotion of free market economics, limited government, and deregulation and privatization to the greatest extent possible. -

2020 Alexander Hamilton Award | Manhattan Institute

5:00PM EDT The Alexander Hamilton Award was instituted to celebrateMANHATTAN and INSTITUTE’S honor TWENTIETH those ANNUAL individuals who have made exceptional contributions to the nation’s civic and intellectual life. We chose to name the award after Hamilton because he was a man of ideas and action. As aide-de-camp to Washington during PRESIDENT, MANHATTAN INSTITUTE the Revolution, the primary author of the Federalist Papers, and the nation’s first REMARKS Treasury secretary, Hamilton, perhaps more than anyone,The Alexander set Hamiltonthe course Award was forinstituted America’s to Paul E. Singer celebrate and honor those individuals who have bright future and prosperity over the net CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, MANHATTAN INSTITUTE two centuries.made exceptional Our contributions honorees to the nation’s this year have eachcivic madeand intellectual Hamiltonian life. We chose contributionsto name the to America,award after and Hamilton the because Manhattan he was a man Institute of is privilegedideas andto action. honor As aide-de-camp them tothis Washington evening. The Alexanderduring the HamiltonRevolution, the Awardprimary author was of instituted the to celebrateFederalist andPapers, honor and the nation’s those first Treasury individuals INTRODUCED BY MICHAEL B. MUKASEY & HEATHER R. HIGGINS who havesecretary, made Hamilton, exceptional perhaps more thancontributions anyone, to the nation’sset the course civic for America’s and bright intellectual future and life. We choseprosperity to name over the the next award two centuries. after Our Hamilton becausehonorees he was this yeara man have eachof made ideas Hamiltonian and action. As aide-de-campcontributions to America,to Washington and the Manhattan during INTRODUCED BY PAUL E. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

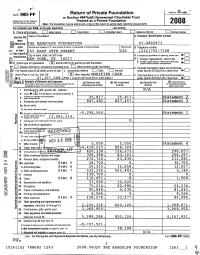

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF C Grossprofitor(^) NOV 2

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-00 2 ' Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service 00 Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2 8 For calendar year 2008 , or tax year beginning ^ and ending M n-- ..u - _--h. I 1 ,..,.,.., .,.h.... I I c^..ol sf,,.n I I Am nAaA rnf,,.n I 1 AAA.n rhsnnn I 1 Clem When Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , HE RANDOLPH FOUNDATION 47-0892971 d print Number and street (or P O box number If mail is not delivered to street address) RooMsulte B Telephone number ortype . 55 EAST 49TH STREET 23D ( 212 ) 752-7148 See Specific City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pentling , check here ► Instructions . NEW YORK , NY 10 017 0 1 • Foreign organizations , check here ► 2. check rgan d att mopum tio85%test, ► H Check type of org anization ^ Section 501 ()()c 3 exempt private foundation ch eck h ere an attac h co mpupu tati on charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation = Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexem pt 0 E It private fou ndation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part 11, co!. (C), line 16) 0 Other (specify ) MODIFIED CASH F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) ► $ 4 7 2 0 7 0 0 8 . -

Strategic Investment in Ideas How Two Foundations Reshaped America

Strategic Investment in Ideas How Two Foundations Reshaped America By John J. Miller The Philanthropy Roundtable Washington, D.C. 2003 Table of Contents Introduction . 5 I The John M. Olin Foundation . 9 History. 9 Higher Education. 15 Law and Economics. 22 The Federalist Society. 28 II The Lynde & Harry Bradley Foundation . 34 History. 34 School Choice . 40 Welfare Reform. 49 III The Road Ahead . 59 Advice for Future Philanthropists. 60 A Note on Sources . 64 About the Author . 67 The Philanthropy Roundtable. 70 5 Introduction Introduction “There are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circu- lation,” wrote Lionel Trilling in 1950, only “irritable mental ges- tures which seek to resemble ideas.” A few years later, Cornell professor Clinton Rossiter wrote an important book with the title, Conservatism in America: The Thankless Persuasion. While per- haps overstating their case, these writers pointed to an important phenomenon: the weakness of conservatism in a country that seemed to have embraced the lib- eral ideals of equality, democracy, and an expanding welfare state. In A small handful of foundations the mid-1950s, often thought to have essentially provided the conser- be a conservative period in vative movement with American life, only William F. Buckley Jr., along with his col- its venture capital, allowing leagues at his fledgling magazine, conservative thinkers to take their National Review, carried the banner case directly to the marketplace of for high-minded conservative ideas. principles. Yet today, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, this appraisal would have to be very nearly reversed. Conservative ideas are in broad circulation, and many believe that they are now ascendant. -

Vision and Philanthropy” Is, Quite Frankly, an Experiment, and an Experiment on Several Levels

— EDITED TRANSCRIPT — HUDSON INSTITUTE’s BRADLEY CENTER FOR PHILANTHROPY AND CIVIC RENEWAL Symposium on V ISION AND P HILANTHROPY Wednesday, February 16, 2005 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. The Ritz-Carlton, Washington, DC Many think the key to success for conservative philanthropy is its willingness to give imaginatively and consistently, and according to a larger, coherent vision of public policy. At this symposium, a group of prominent conservative thinkers, writers, and philanthropists came together to discuss two questions: “What is the conservative vision for America today?” and “How can philanthropy best promote it?” Short texts written by some of the panelists (available online at http://pcr.hudson.org) served as a starting point for the discussion. University of Chicago Senior Lecturer and Hudson Institute Senior Fellow AMY KASS served as moderator. Keynote speaker for the luncheon discussion was PETER WEHNER, Deputy Assistant to the President and Director of Strategic Initiatives, White House. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Panelists 2 8:30 to 10:00 a.m.: Panel Discussion on Conservative Vision 3 10:15 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.: Panel Discussion Continues: Philanthropy’s 23 Role in Realizing the Vision 12:00 to 1:30 p.m.: Luncheon and Keynote Speech by Peter Wehner 42 Participant Biographies 51 Transcript by: Federal News Service, Washington, D.C. Edited by Krista Shaffer, Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal V ISION AND P HILANTHROPY A Bradley Center Symposium PANELISTS Stuart Butler Leon Kass Vice President, The Heritage Foundation Hertog Fellow, American Enterprise Institute Linda Chavez David Keene President, Center for Equal Opportunity Chairman, American Conservative Union Michael Cromartie William Kristol Vice President, Ethics and Public Policy Center Editor, The Weekly Standard Barbara Elliott Leonard Leo Founder and President, Center for Renewal Executive Vice President, The Federalist Society Pete du Pont Heather Mac Donald Board Member, Lynde & Harry Bradley John M. -

Agenda Setting: a Wise Giver's Guide to Influencing Public Policy

AGENDA SETTING MILLER Agenda Setting A Wise Giver’s Guide to Influencing Public Policy Donating money to modify public thinking and government policy has now taken its place next to service-centered giving as a constructive branch of philanthropy. Many donors now view public-policy reform as a necessary adjunct to their efforts to improve lives directly. This is perhaps inevitable given the mushrooming presence of government in our lives. In 1930, just 12 percent of U.S. GDP was consumed by government; by 2012 that had tripled to 36 percent. Unless and until that expansion of the state reverses, it is unrealistic to expect the philanthropic sector to stop trying to have a say in public policies. Sometimes it’s not enough to build a house of worship; one must create policies that make it possible for people to practice their faith freely within society. Sometimes it’s not enough to pay for a scholarship; one must change laws so that high-quality schools exist for scholarship recipients to take advantage of. Yet public-policy philanthropy has special ways of mystifying and frustrating practitioners. It requires understanding of governmental practice, interpretation of human nature, and some philosophical perspective. Public-policy philanthropists may encounter opponents operating from different principles who view them as outright enemies. Moreover, public-policy struggles never seem to end: victories and ZINSMEISTER and ZINSMEISTER one year become defeats the next, followed by comebacks, then setbacks, and on and on. This book was written to help donors navigate all of those obstacles. It draws Agenda on deep history, and rich interviews with the very best practitioners of public- policy philanthropy in America today. -

John Train's Fascist Capture of Television

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 33, Number 39, September 29, 2006 shares a seat on the Ditchley Foundation board of governors with Baroness Liz Symons of Vernham Dean, a former Tony Blair Minister of State for International Trade and Invest- ment, friend of Mrs. Lynne Cheney, and an active player in John Train’s Fascist recent AFF-steered filthy slander operations against Lyndon LaRouche. Capture of Television ‘Mother’ England by Anton Chaitkin Above all else, John Train is a particular species of rabid Anglophile (“American Tory”), whose attachments to the City of London financial oligarchy and the intelligence and John Train’s mentor, Sir Cyril Northcote Parkinson, told him policy institutions of the British Commonwealth are primary. to “capture television” for the right wing, because it was more A source familiar with Train’s operations bluntly described important than the schools, and that’s exactly what Train set him as an appendage of the London IISS. out to do. In 1987, four years after Train met with representa- Furthermore, Train’s personal financial empire is, in fact, tives of the bankers’ CIA faction, U.S. Justice Department, centered more in Britain and continental Europe than in the private foundation moguls, and selected media outlets in his United States. In 1984, Train Smith Counsel, the Wall Street “Get LaRouche” salon, Train created the Northcote Parkinson firm 75% owned by John Train, went through a financial Fund to use those same forces to gain the control Sir Cyril restructuring, with English Association Trust (EAT) of Lon- had mandated. don purchasing 50% controlling interest. -

Jon A. Shields Government Department Claremont Mckenna College

Jon A. Shields Government Department Claremont McKenna College Education: Ph.D., University of Virginia, Politics, 2006 B.A., University of California, Santa Barbara, Law and Society, 1997 (High Honors) Professional Experience: Associate Professor, Department of Government, Claremont McKenna College, 2012- (Assistant Professor, 2008-2012) Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, CU—Colorado Springs, 2007-2008 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Cornell University, 2006-2007 Research Assistant, Governance Studies, Brookings Institution, 1998-2000 Fellowships, Grants, and Professional Service: Associated Faculty, Salvatori Center, Claremont Mckenna College, 2018- National Fellowship Advisory Council, Jefferson Scholars Foundation, 2017-2018 Member, Heterodox Academy, 2015- Editorial Advisory Board, Society, 2011- Research grant, Randolph Foundation, 2018-19 Course development grant, Koch Foundation, 2017, 2019 Course development grant, Claremont McKenna College, Summer 2016 Research grant, Earhart Foundation, 2014-15 Research grant, Randolph Foundation, 2011-13 Course development grant, Institute for the Study of Secular Society and Culture, 2008-09 Dissertation Fellow, Center on Religion and Democracy, University of Virginia, 2005-06 Dissertation Fellow, Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia, 2004-05 President’s Fellowship, University of Virginia, 2001-03 Bradley Fellowship, University of Virginia, 2000-04 1 Books: Trump’s Democrats (Brookings Institution Press, 2020), with Stephanie -

2012 Annual Report

2012 AN NUAL RE PORT BLUE OCEAN INSTITUTE “Julie Packard was among the first and remains among the foremost rivers of the ocean conservation movement.” —Carl Safina Monterey Bay Aquarium; Photo © Tom O’Neil DONOR PROFILE Julie Packard The David and Lucile Packard Foundation For more than 45 years, the David and Lu - Bay Aquarium, works each day from her of- of national ocean policy. Julie Packard was cile Packard Foundation has worked with fice on Cannery Row on the California the 1998 recipient of the Audubon Medal for partners around the world to improve the coast. She understands the power of the Conservation. lives of children, families and communities— human connection to wildlife and is pas - A note of deep gratitude: The David and and to restore and protect our planet. The sionate about sharing opportunities for Lucile Packard Foundation’s long-term sup - Foundation’s work in science and conserva - others to experience it, too. port has funded Carl Safina’s work continu - tion is having a profound impact through its Her commitment to advancing ocean ously since 1990. First through his Living fellowships in science and engineering, and conservation has been demonstrated Ocean’s Program at National Audubon its dedication to marine conservation and through the Aquarium and far beyond. She Society and then through Blue Ocean sustainable fisheries. Its vision for marine serves on numerous boards including the Institute, Packard’s generosity has made conservation has inspired a global legacy, California Nature Conservancy, the Monterey possible an enormous proportion of what and as importantly, a legacy close to home: Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and the Safina and his groups have accomplished the Packard children founded the acclaimed David and Lucile Packard Foundation. -

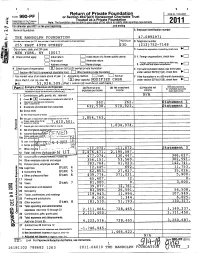

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

c I Return of Private Foundation O M B No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)( 1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation .4 Internal Revenue Service Note. Ti ndation may be able to use a coot/ of this return to satisfy state reporting n 2011 For calendar year 2011 or tax year begin , and ending n( Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE RANDOLPH FOUNDATION 47-0892971 Room/suite .wl Number and street (or P O box number if mail Is not delivered to street address) B Telephone number 255 EAST 49TH STREET 3D ( 212 ) 752-7148 City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application Is pending , check here NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Fore ign organizations , check here 0 Final return Amended return Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, Address Chan g e Name Chan g e 2. check here and attach computation H Check type of organization DX Section 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated 0 Secti on 4947 (a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable p rivate found ation under section 507(b)(1 )(A), check here ► I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash 0 Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month term ination (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) [K]Other( specify ) MODIFIED CASH under secti on 507 (b)(1)(B), check here column ( must be on cash basis.) ► $ 5 3 , 9 2 8 , 5 0 9 .