Implications for Western Australia of Hydraulic Fracturing for Unconventional Gas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospect Magazine June 2016

WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S INTERNATIONAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE June – August 2016 $3 (inc GST) Print post approved PP 665002/00062 approved Print post IRON STATE Western Australia marks 50 years of iron ore exports DEPARTMENT OF STATE DEVELOPMENT International Trade and Investment Level 6, 1 Adelaide Terrace East Perth, Western Australia 6004 • AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 8 9222 0555 • Fax: +61 8 9222 0505 Email: [email protected] • www.dsd.wa.gov.au INTERNATIONAL OFFICES Europe — London Government of Western Australian – European Office 5th floor, The Australia Centre Corner of Strand and Melbourne Place London WC2B 4LG • UNITED KINGDOM Tel: +44 20 7240 2881 • Fax: +44 20 7240 6637 Email: [email protected] • www.wago.co.uk twitter.com/@wagoEU India — Mumbai Western Australian Trade Office This edition of Prospect marks a significant milestone in Western Australia’s resources 93 Jolly Maker Chambers No 2 sector – 50 years of iron ore exports from the State. 9th floor, Nariman Point • Mumbai 400 021 • INDIA Tel: +91 22 6630 3973 • Fax: +91 22 6630 3977 Three first shipments of iron ore exports commenced in 1966, with a start-up tonnage of Email: [email protected] • www.watoindia.in 2.2 million tonnes per annum (story page 2). Indonesia — Jakarta Our industry has grown over the past 50 years to a total of 9 billion tonnes of iron ore exports Western Australia Trade Office Level 48, Wisma 46, Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kavling 1 and Western Australia is now the world’s largest iron ore exporter. Jakarta Pusat 10220 • INDONESIA Tel: +62 21 574 8834 • Fax: +62 21 574 8888 Western Australian company Roy Hill shipped its first ore in December and the company is Email: [email protected] continuing to ramp up production this year (story page 7). -

Federal Political Update

CCH Parliament Western Australian Political Update Issue: 47 of 2010 Date: 29 November 2010 For all CCH Parliament enquiries, contact: CCH Parliament Phone 02 6273 2070 Fax 02 6273 1129 A brand of CCH Australia, a Wolters Kluwer business. PO Box 4746 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Timely, Accurate, Relevant... CCH, The Professional's First Choice ISSN: 1442-7990 Western Australian Political Update A weekly summary report of political, government and legislative news Portfolio Index – please select: Aboriginal Affairs............................................................................................................................... 3 Education .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Emergency Services ......................................................................................................................... 4 Energy............................................................................................................................................... 4 Environment...................................................................................................................................... 4 Family & Community Services .......................................................................................................... 5 Finance ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Foreign Affairs.................................................................................................................................. -

P4793c-4801A Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Katsambanis

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 12 August 2020] p4793c-4801a Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Katsambanis IRON ORE PROCESSING (MINERALOGY PTY. LTD.) AGREEMENT AMENDMENT BILL 2020 Second Reading Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MRS L.M. HARVEY (Scarborough — Leader of the Opposition) [2.56 pm]: I rise to continue my remarks about this amending legislation. I put on the record once again that the position of the Liberal Party room was a consensus position to not oppose this legislation. I would like to get on the record that we do not support the actions of Clive Palmer, which is why we are not opposing this legislation. During question time, I asked the Premier whether he would support a short sharp committee inquiry. It is ridiculous to say that the suggestion of a committee inquiry or that contentious legislation go to a committee to potentially strengthen it is in any way, shape or form showing that the legislation is not supported. That is ridiculous. The amending legislation in front of us is backdated to have effect from 11 August. It was read in just after 5.00 pm yesterday so that Mr Palmer and his lawyers could not get wind of it and could not lodge a writ in court. It needed to be read in yesterday after that opportunity had lapsed. The legislation is backdated to be effective from yesterday, 11 August 2020, at around about 5.00 pm. Should the upper house choose to send it to a committee to potentially strengthen it and ward off a potential High Court challenge, it could be done and dusted by 15 September. -

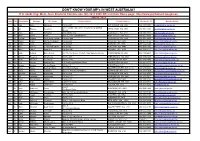

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

Western Councillor ISSUE 108 | JUN/JUL 2020

Western Councillor ISSUE 108 | JUN/JUL 2020 A STELLAR CROWD LOCAL GOVERNMENT P04 LOCAL GOVERNMENT P22 IN THE SPOTLIGHT AWARD WINNERS Local governments working together. At LGIS, protecting our local government members is what we do. We make sure our members have the right cover to suit their needs. If disaster strikes, our local government specialists help get them, and their community, back on their feet as soon as possible. It’s our members who make Western Australia such a great place to live – their roads get us around, we meet in their libraries and recreation centres, they manage our waste, and provide connection for the elderly. Every day they provide the countless services and support which makes us a community. We believe that’s worth protecting. To find out how you can get the most out of your LGIS membership, visit lgiswa.com.au or call 9483 8888. LOCAL GOVERNMENT Peer Support Team BRINGING CLARITY TO A practical way to provide mediation and conciliation support to Local Governments COMPLEXITY in Western Australia. The Peer Support Team is of confl ict and reduce the need for an initiative between the WA formal investigations or enquiries. The team will meet with the affected Australia’s Local Government sector. Local Government Association (WALGA) and Local Government Councillors and staff individually, as Our team of highly experienced lawyers strive for clarity and well as in a group setting, allowing Professionals WA. excellence in our legal advice to our clients. all parties to freely express their The team was formed to provide views in a neutral environment. -

P9999c-10000A Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Colin Barnett; Speaker; Mr Peter Watson

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY - Thursday, 26 November 2009] p9999c-10000a Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Colin Barnett; Speaker; Mr Peter Watson PARLIAMENTARY PRECINCT — FUTURE ACCOMMODATION NEEDS 966. Mr W.R. MARMION to the Premier: Since I have been elected to this Parliament I have become aware that the buildings and facilities within the parliamentary precinct do not adequately cater for the roles and functions of Parliament, especially for committees and support services. I am also aware of the limitations and rising rental costs in the central business district, where a number of government offices and agencies are located. Can the Premier please update the house on what the government is doing about the future accommodation needs of the Parliament and other government offices? Mr C.J. BARNETT replied: I thank the member for Nedlands for the question. I will answer the second part first. The lease on Governor Stirling Tower, which is the main accommodation for government and which covers the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, the Public Sector Commission, the Department of Treasury and Finance and the Department of Indigenous Affairs, expires in June 2012. Although the government would like to continue that lease, it is understood that the owner of the building is not prepared to do so. We will endeavour to gain some extension, but as it looks at the moment, Governor Stirling Tower will no longer be available after June 2012 as the principal accommodation for my office and the central agencies of the government. Somewhat coincidentally, I received a letter, dated 24 September, from the Speaker and the President raising issues about accommodation for the Parliament. -

Federal Political Update

CCH Parliament Western Australian Political Update Issue: 6 of 2012 Date: 6 February 2012 For all CCH Parliament enquiries, contact: CCH Parliament Phone 02 6273 2070 Fax 02 6273 1129 A brand of CCH Australia, a Wolters Kluwer business. PO Box 4746 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Timely, Accurate, Relevant... CCH, The Professional's First Choice ISSN: 1442-7990 Western Australian Political Update A weekly summary report of political, government and legislative news Portfolio Index – please select: Aboriginal Affairs............................................................................................................................... 3 Education .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Energy............................................................................................................................................... 5 Environment...................................................................................................................................... 5 Food Industry .................................................................................................................................... 6 Foreign Affairs................................................................................................................................... 6 Health................................................................................................................................................ 6 Housing & Property.......................................................................................................................... -

P1391b-1394A Mr Mark Mcgowan; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Rundle

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 21 June 2017] p1391b-1394a Mr Mark McGowan; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Rundle PETER VERNON JONES, AM Condolence Motion MR M. McGOWAN (Rockingham — Premier) [12.01 pm] — without notice: I move — That this house records its sincere regret at the death of Mr Peter Vernon Jones, AM, and tenders its deep sympathy to his family. I acknowledge members of Peter’s family who are in the gallery today for this important affirmation of someone who was a very significant figure in this Parliament in the time he was here, and in the community before and after his parliamentary career. Peter Jones was elected as the member for Narrogin in 1974 and served his electorate and the state diligently until his retirement 12 years later in 1986. Peter was born in Launceston, Tasmania, in 1933, to parents Harold Vernon Jones, a headmaster, and Annie May Simmons. In Hagley, Tasmania, where he had taken up a life of farming, Peter married his wife, Toni, in 1960. Eight years later, Peter and his young family moved to Western Australia to pursue farming opportunities in an effort to secure their family’s future. The Jones’ settled in Narrogin, where they became successful wool, meat and grain growers. In 1974 Peter took the leap from being a successful farmer and board member of the WA Barley Marketing Board to running for the Legislative Assembly, and he won. Looking back on his parliamentary career, Peter’s achievements are many and enduring. His 12 years in Parliament were turbulent in that they included three splits in his own party, which saw him enter Parliament as a member of the Country Party and retire as a member of the Liberal Party. -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

Minister for Mines & Petroleum

MINISTER FOR MINES & PETROLEUM; HOUSING Your Ref: 814/2186 Our Ref: 42-31986 Senator the Han Nigel Scullion Minister for Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Mr'er A!t~ ~I Thank you for your letter of 22 July 2014 regarding essential and municipal services to remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. I acknowledge the offer of a one-off payment of $90 million from the Commonwealth Government on the basis that the State takes on sole responsibility for providing essential and municipal services to remote Aboriginal communities from 1 July 2015. Unfortunately, I was not able to meet the timeline of 31 July 2014 you requested as this offer will need to be considered by Cabinet prior to any formal response. I will endeavour to have this matter scheduled as a high priority and would hope that I can respond substantively by the end of August. In the meantime I am hopeful that progress can be made towards a broader bilateral agreement as proposed in the Premier's letter to the Prime Minister, where the State and the Commonwealth can more closely align our resources and efforts around priority areas. Yours sincerely HON BILL MARMION MLA MINISTER FOR MINES AND PETROLEUM; HOUSING 2 AUG 2014 cc: Hon Colin Barnett MLA, Premier Hon Tony Simpson MLA, Minister for Local Government Hon Peter Collier MLC, Minister for Indigenous Affairs Level 29, 77 81 Georges Terrace, Perth, Western Australia 6000 Telephone: +61 865526800 Facsimile: +61 865526801 Email: [email protected] www.ministers.wa.gov.au/marmion OFFICE OF'THE HON BILL MARMION MLA JlAINISTER FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Reference: C14179440 The Hon Bill Mannion MLA Minister for JlAInes and Petroleum; Housing Level 29, 77 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 ,&w Dear~er Thank you for your letter of, 18 September 2014 confinning acceptance oftbe Commonwealtb Government's offer of, $90 million as a final one-ofl)payment for municipal and essential services. -

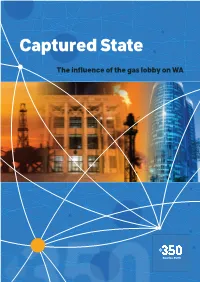

Captured-State-Report.Pdf

KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map. IndependentParliamentary KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map. CapturedIndependentParliamentary State The influence of the gas lobby on WA KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map. -

WHITE HOT Print Post Approved PP 665002/00062 Approved Print Post

WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S INTERNATIONAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE December 2016 – February 2017 $3 (inc GST) WHITE HOT Print post approved PP 665002/00062 approved Print post Lithium plant adds value to WA resources development DEPARTMENT OF STATE DEVELOPMENT International Trade and Investment Level 6, 1 Adelaide Terrace East Perth, Western Australia 6004 • AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 8 9222 0555 • Fax: +61 8 9222 0505 Email: [email protected] • www.dsd.wa.gov.au INTERNATIONAL OFFICES Europe — London Government of Western Australian – European Office 5th floor, The Australia Centre Corner of Strand and Melbourne Place London WC2B 4LG • UNITED KINGDOM Tel: +44 20 7240 2881 • Fax: +44 20 7240 6637 Email: [email protected] • www.wago.co.uk twitter.com/@wagoEU The year’s end sees Western Australia basking in gold and shimmering in the silver light of India — Mumbai lithium with the State’s resources sector continuing to shine. Western Australian Trade Office 93 Jolly Maker Chambers No 2 Western Australia is the world’s biggest gold province, with the value of the State’s gold sales 9th floor, Nariman Point • Mumbai 400 021 • INDIA increasing for the second consecutive year to reach a record $10 billion. Tel: +91 22 6630 3973 • Fax: +91 22 6630 3977 Gold exploration expenditure in the State has surged throughout 2016 and investment Email: [email protected] • www.watoindia.in interest in the State’s gold sector is on the rise (see story page 4). Indonesia — Jakarta Western Australia Trade Office The Western Australian South West town of Greenbushes is home to the world’s largest Level 48, Wisma 46, Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kavling 1 single hard-rock deposit of lithium.