Submarine Rudder Stern-Plane Configuration for Optimum Manoeuvring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1850 Pro Tiller

1850 Pro Tiller Specs Colors GENERAL 1850 PRO TILLER STANDARD Overall Length 18' 6" 5.64 m Summit White base w/Black Metallic accent & Tan interior Boat/Motor/Trailer Length 21' 5" 6.53 m Summit White base w/Blue Flame Boat/Motor/Trailer Width 8' 6" 2.59 m Metallic accent & Tan interior Summit White base w/Red Flame Boat/Motor/Trailer Height 5' 10" 1.78 m Metallic accent & Tan interior Beam 94'' 239 cm Summit White base w/Storm Blue Metallic accent & Tan interior Chine width 78'' 198 cm Summit White base w/Silver Metallic Max. Depth 41'' 104 cm accent & Gray interior Max cockpit depth 22" 56 cm Silver Metallic base w/Black Metallic accent & Gray interior Transom Height 25'' 64 cm Silver Metallic base w/Blue Flame Deadrise 12° Metallic accent & Gray interior Weight (Boat only, dry) 1,375# 624 kg Silver Metallic base w/Red Flame Metallic accent & Gray interior Max. Weight Capacity 1,650# 749 kg Silver Metallic base w/Storm Blue Max. Person Weight Capacity 6 Metallic accent & Gray interior Max. HP Capacity 90 Fuel Capacity 32 gal. 122 L OPTIONAL Mad Fish graphics HULL Shock Effect Wrap Aluminum gauge bottom 0.100" Aluminum gauge sides 0.090'' Aluminum gauge transom 0.125'' Features CONSOLE/INSTRUMENTATION Command console, w/lockable storage & electronics compartment, w/pull-out tray, lockable storage drawer, tackle storage, drink holders (2), gauges, rocker switches & 12V power outlet Fuel gauge Tachometer & voltmeter standard w/pre-rig Master power switch Horn FLOORING Carpet, 16 oz. marine-grade, w/Limited Lifetime Warranty treated panel -

An Orientation for Getting a Navy 44 Underway

Departure and return procedure for the Navy 44 • Once again, the Boat Information Book for the United States Naval Academy Navy 44 Sailing Training Craft is the final authority. • Please do not change this presentation without my permission. • Please do not duplicate and distribute this presentation without the permission of the Naval Academy Sailing Training Officer • Comments welcomed!! “Welcome aboard crew. Tami, you have the helm. If you’d be so kind, take us out.” When we came aboard, we all pitched in to ready the boat to sail. We all knew what to do and we went to work. • The VHF was tuned to 82A and the speakers were set to “both”. • The engine log book & hernia box were retrieved from the Cutter Shed. • The halyards were brought back to the bail at the base of the mast, but we left the dockside spinnaker halyard firmly tensioned on deck so boarding crew could use it to aid boarding. • The sail and wheel covers were removed and stored below. • The reef lines were attached and laid out on deck. • The five winch handles were placed in their proper holders. • The engine was checked: fuel level, fuel lines open, bilge level/condition, alternator belt tension, antifreeze level, oil and transmission level, RACOR filter, raw water intake set in the flow position, engine hours. This was all entered into the log book. • Sails were inventoried. We use the PESO system. We store sails in the forward compartment with port even, starboard odd. •The AC main was de-energized at the circuit panel. -

Sea Kayak Handling Sample Chapter

10 STERN RUDDERS Stern rudders are used to keep the kayak going in a straight line and make small directional changes when on the move. The stern rudder only works if the kayak is travelling at a reasonable speed, but it has many applications. The most common is when there is a following wind or sea pushing the kayak along at speed. In this situation, forward sweep strokes are not quick enough to have as much effect as the stern rudder. A similar application is when controlling the kayak while surfi ng. A more ‘gentle’ application is when moving in and out of rocks, caves and arches at slower speeds. Here, the stern rudder provides control and keeps the kayak on course in these tight spaces. Low angle stern rudder This is the classic stern rudder and works well to keep the kayak running in a straight line. It is best combined with the push/pull method of turning with a stern rudder (see below). • The kayak must be moving at a reasonable speed. • Fully rotate the body so that both hands are out over the side. • Keep looking forwards. • Place the blade nearest the stern of the kayak in the water as far back as your rotation allows. • The blade face should be parallel to the side of the kayak so that it cuts through the water and you feel no resistance. 54 • The blade should be fully submerged and will act like a rudder, controlling the direction of the kayak. • The front hand should be across the kayak and at a height between your stomach and chest. -

Know About Boating Before You Go Floating

Know About Boating Before You Go Floating KEY TERMS All-around white light: Navigation light that Gunwale: Upper edge of a boat’s side. is visible in all directions around the boat from Hull: The main body of a boat. 2 miles away. Port: The left side of a boat. Bow: The front part of a boat. Propeller: A device with two or more blades Buoy: An object that floats on the water in that turn quickly and cause a boat to move. a bay, river, lake or other body of water and Sidelights: Red (port side) and green provides information to boats. (starboard side) navigation lights on a boat, Capsize: To turn a craft upside down in visible from 1 mile away. the water. Skipper: The person who commands a boat. Cleat: A wooden or metal fitting on the deck Starboard: The right side of a boat. of a boat. It has two projecting horns around which a rope or line may be tied. Stern: The back part of a boat. OBJECTIVES After completing this lesson, students will be able to: zz Name the main parts of a boat. zz Explain some boating terms. zz Describe some important safety equipment that should be on a boat. zz Demonstrate putting on a life jacket. zz Explain how to board a boat. zz Understand how to balance a boat. zz Explain what to do if a boat capsizes (turns over). MATERIALS, EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES zz Poster: Know About Boating Before You Go Floating zz Several Type II and/or Type III life jackets (in the various sizes that would fit the students) zz Mat or tape to create outline of boat zz Chairs (6) zz Watch or clock with a second hand zz Crayons, markers -

Skilful Vessel Handling

Skilful Vessel Handling Capt. Øystein Johnsen MNI Buskerud and Vestfold University College March 2014 Manoeuvring of vessels that are held back by an external force This consideration is written in belated wisdom according to the accident of Bourbon Dolphin in April 2007 When manoeuvring a vessel that are held back by an external force and makes little or no speed through the water, the propulsion propellers run up to the maximum, and the highest sideways force might be required against wind, waves and current. The vessel is held back by 1 800 meters of chain and wire, weight of 300 tons. 35 knops wind from SW, waves about 6 meter and 3 knops current heading NE has taken her 840 meters to the east (stb), out of the required line of bearing for the anchor. Bourbon Dolphin running her last anchor. The picture is taken 37 minutes before capsizing. The slip streams tells us that all thrusters are in use and the rudders are set to port. (Photo: Sean Dickson) 2 Lack of form stability I Emil Aall Dahle It is Aall Dahle’s opinion that the whole fleet of AHT/AHTS’s is a misconstruction because the vessels are based on the concept of a supplyship (PSV). The wide open after deck makes the vessels very vulnerable when tilted. When an ordinary vessel are listing an increasingly amount of volume of air filled hull is forced down into the water and create buoyancy – an up righting (rectification) force which counteract the list. Aall Dahle has a doctorate in marine hydrodynamics, has been senior principle engineer in NMD and DNV. -

After 88 Years - Four-Masted Barque PEKING Back in Her Homeport Hamburg

Four-masted barque PEKING - shifting Wewelfsfleth to Hamburg - September 2020 After 88 Years - Four-masted Barque PEKING Back In Her Homeport Hamburg Four-masted barque PEKING - shifting Wewelfsfleth to Hamburg - September 2020 On February 25, 1911 - 109 years ago - the four-masted barque PEKING was launched for the Hamburg ship- ping company F. Laeisz at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg. The 115-metres long, and 14.40 metres wide cargo sailing ship had no engine, and was robustly constructed for transporting saltpetre from the Chilean coast to European ports. The ship owner’s tradition of naming their ships with words beginning with the letter “P”, as well as these ships’ regular fast voyages, had sailors all over the world call the Laeisz sailing ships “Flying P-Liners”. The PEKING is part of this legendary sailing ship fleet, together with a few other survivors, such as her sister ship PASSAT, the POMMERN and PADUA, the last of the once huge fleet which still is in active service as the sail training ship KRUZENSHTERN. Before she was sold to England in 1932 as stationary training ship and renamed ARETHUSA, the PEKING passed Cape Horn 34 times, which is respected among seafarers because of its often stormy weather. In 1975 the four-master, renamed PEKING, was sold to the USA to become a museum ship near the Brooklyn Bridge in Manhattan. There the old ship quietly rusted away until 2016 due to the lack of maintenance. -Af ter returning to Germany in very poor condition in 2017 with the dock ship COMBI DOCK III, the PEKING was meticulously restored in the Peters Shipyard in Wewelsfleth to the condition she was in as a cargo sailing ship at the end of the 1920s. -

Cornshuckers and San

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

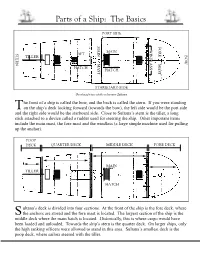

Parts of a Ship: the Basics

Parts of a Ship: The Basics PORT SIDE MAIN FORE MAIN WINDLASS STERN AFT BOW TILLER MAST MAST HATCH HATCH STARBOARD SIDE Overhead view of the schooner Sultana he front of a ship is called the bow, and the back is called the stern. If you were standing T on the ship’s deck looking forward (towards the bow), the left side would be the port side and the right side would be the starboard side. Close to Sultana’s stern is the tiller, a long stick attached to a device called a rudder used for steering the ship. Other important items include the main mast, the fore mast and the windlass (a large simple machine used for pulling up the anchor). POOP DECK QUARTER DECK MIDDLE DECK FORE DECK MAIN TILLER HATCH ultana’s deck is divided into four sections. At the front of the ship is the fore deck, where S the anchors are stored and the fore mast is located. The largest section of the ship is the middle deck where the main hatch is located. Historically, this is where cargo would have been loaded and unloaded. Towards the ship’s stern is the quarter deck. On larger ships, only the high ranking officers were allowed to stand in this area. Sultana’s smallest deck is the poop deck, where sailors steered with the tiller. Parts of a Ship: The Basics NAME: ____________________________________________ DATE: ____________ DIRECTIONS: Use information from the reading to answer each of the following questions in a complete sentence. 1. What is the front of a ship called? What do you call the back end of a ship? 2. -

Glossary of Terms

Glossary of Terms Below are new words for our Glossary of Terms based on AB Barlow’s activities the last couple of weeks. To see all the terms from AB Barlow’s past activities, please scroll down. Battle of Cape St. Vincent – one of the first battles of the Anglo-Spanish War (1796-1808). The battle was a decisive English victory and saw four Spanish ships of the line captured by the British; two by Horatio Nelson Battle of Flamborough Head – a battle fought during the American War of Independence during which Captain John Paul Jones captured the British frigate Serapis even as his own ship, Bonhomme Richard, sank out from under him Boarding – the act of sending sailors or soldiers from one’s own ship to an enemy ship for the purpose of capturing the other vessel. In modern context, boarding can also occur for more peaceful purposes such as a safety or customs inspection Brig – a ship with two masts, both carrying square sails. Also, a jail located on board a ship Cutting Out – the act of attacking a ship from small boats filled with sailors or marines. Often used as a surprise tactic Fighting Top – a platform part way up a ship’s mast used as a firing position by sharpshooters during a naval engagement First-Rate – the largest warships in the now-obsolete Royal Navy ranking system. Generally, first-rates mounted around 100 carriage guns Frigate – a small, fast warship; usually built for maneuverability and speed over firepower Gangway – traditionally, a narrow passage connecting a ship’s quarterdeck and forecastle. -

Glossary of Terms (List Will Be Updated on a Continual Basis)

Glossary of Terms (list will be updated on a continual basis) The words below are new to our Glossary of Terms. These words will be integrated into our overall list, which is below the new words. Chafing Gear – pads, mats, ropes and other materials tied around pieces of rigging to protect them from rubbing on spars and other parts of the rig Foxes – pieces of scrap line made by twisting together several strands or yarns Hand, Reef & Steer – traditional qualifications of an able seaman, to hand is to take in or furl a sail and to reef is to shorten sail and to steer is to take a turn at the helm Helmsman – the Sailor stationed at the ship’s helm (wheel) in charge of steering and keeping a straight course Marline – light, two-stranded line; often tarred and used for seizings Marlinespike – a tapered metal spike used to separate strands of rope, untie knots and as a handle for hauling away on seizings, whippings, etc. Merchant Service – the industry concerned with commercial shipping ventures (i.e., non-military) Rating – denotes a Sailor’s rank, responsibilities and rate of pay (i.e., able seaman, ordinary seaman, boy, etc.) Rigging – the lines and ropes that hold the masts, spars and sails Sail Making – the work of mending, replacing and sewing sails; the sail maker would often advise on how best to set and trim sails Seizing – method of binding two ropes or objects together involving wrapping them tightly with line Splice – weaving together to strands of separate ropes to form one longer rope Watches – division of labor aboard ship; the -

True Wind Angle

User’s Guide by TrueWind David Burch About TrueWind...................................................................2 How to use TrueWind...........................................................3 Definitions Wind direction............................................................4 Apparent wind............................................................4 Apparent wind angle..................................................4 Apparent wind speed.................................................. 5 True wind angle.......................................................... 5 True wind speed ......................................................... 5 Speed .......................................................................... 6 Heading ...................................................................... 6 Discussion Telltales ...................................................................... 7 Electronic wind instruments....................................... 7 True wind versus apparent wind ................................ 8 Tips, tricks, and special cases .................................... 8 How to find true wind Reading the water....................................................... 9 Formulas and diagrams .............................................. 10 Graphical method ....................................................... 12 2 Starpath TrueWind INDEX About Starpath TrueWind Starpath TrueWind is a Windows program designed to compute very conveniently true wind from apparent wind for use in maneuvering and weather analysis. -

Knowing Your Boat Means Knowing Its Wake

Knowing your boat means knowing its wake This is an illustrated guide to wave wake that expands upon the basics outlined in the low wake guide “Wake up? Slow Down”, which is available at: http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Guide-to-Low-Wave-Wake-Boating.pdf We all know ‘stow it – don’t throw it’ but what about what Bryce Courtenay’s Yowie said to the Dirty Rotten Rubbish Grumpkin: “not thinking is the same as not caring”? Here are 18 illustrations to help boaters think about their wake and its potential erosive impacts in sheltered, restricted or shallow waters. Environmental effects of wave wake In the open sea wave wake is likely to have little environmental effect since the waves are small compared to those that might occur naturally. It’s a very different matter in sheltered waters like riverine estuaries. The soft banks and beds of many Tasmanian waterways are vulnerable to damage from boat wake and prop wash. Typical easily-affected landforms include estuaries, inlets, lakes and lagoons; places where natural wave energy tends to be low. Banks of peat or mud, shallow lagoons or lakes with muddy beds and sandy deposits in upper estuaries are all areas of risk. Wake striking the banks can cause rapid and severe erosion, exposing the roots of vegetation and causing the banks to collapse. Wake impact and prop wash can also churn up fine bed sediments – the impact on bed and banks degrades the aquatic environment for plants and animals. In some popular boating and cruising areas, the effects of wake damage have been severe – for example, on the lower Gordon River, long stretches of bank have been washed away, with mature Huon pines and myrtles toppling into the river.