Cornshuckers and San

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smithsonian Folklife Festival

I SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL .J HAITI Freedom and Creativity from the Mountains to the Sea NUESTRA MUSICA Music in Latino Culture WATER WAYS Mid-Atlantic Maritime Communities The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival brings together exemplary keepers of diverse traditions, both old and new, from communities across the United States and around the world. The goal of the Festival is to strengthen and preserve these traditions by presenting them on the National Mall, so that the traciition-bearers and the public can connect with and learn from one another, and understand cultural differences in a respectful way. Smiths (JNIAN Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 750 9th Street NW Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20560-0953 www.folklife.si.edu © 2004 by the Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 Editor: Carla Borden Associate Editors: Frank Proschan, Peter Seitel Art Director: Denise Arnot Production Manager: Joan Erdesky Graphic Designer: Krystyn MacGregor Confair Printing: Schneidereith & Sons, Baltimore, Maryland FESTIVAL SPONSORS The Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds; Smithsonian trust tunds; contributions from governments, businesses, foundations, and individuals; in-kind assistance; and food, recording, and cratt sales. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. Major hinders for this year's programs include Whole Foocis Market and the Music Performance Fund. Telecommunications support tor the Festival has been provided by Motorola. Nextel. Pegasus, and Icoiii America. Media partners include WAMU 88.5 FM, American University Radio, and WashingtonPost.com. with in-kind sup- port from Signature Systems and Go-Ped. Haiti: Frcciioin and Creativity fnvu the Moiiiitdiin to the Sea is produced in partnership with the Ministry of Haitians Living Abroad and the Institut Femmes Entrepreneurs (IFE), 111 collaboration with the National Organization for the Advancement of Haitians, and enjoys the broad-based support of Haitians and triends ot Haiti around the world. -

Spectacular Summer Decoy Auction Sunday & Monday, July 28 - 29, 2013 Cape Codder Resort and Hotel • Hyannis, MA Phone: (888) 297-2200

Ted and Judy Harmon present: Spectacular Summer Decoy Auction Sunday & Monday, July 28 - 29, 2013 Cape Codder Resort and Hotel • Hyannis, MA Phone: (888) 297-2200 Preview: Saturday, July 27, 6-9 pm • Sunday, July 28, 9-11 am • Monday, July 29, 8-10 am Sale: Sunday, July 28, 11 am • Monday, July 29, 10 am www.decoysunlimitedinc.net e-mail: [email protected] TERMINOLOGY: XOP - Excellent Original Paint XOC - Excellent Original Condition OP - Original Paint T/U - Touch Up For alternative or phone bidding please call Ted Harmon at (508) 362-2766 For more information contact: Ted Harmon, P.O. Box 206, West Barnstable, MA 02668 • (508) 362-2766 See conditions of sale on back of catalog. 1 Reflections Ted and Judy Harmon It’s been quite a year. There were lots of speed bumps in the road but here I am once again with a number of nice decoys to fit every pocketbook thanks to a lot of help from family, some very good friends and loyal consignors. Due to health problems I was unable to attend the Mid-West Decoy Collector’s Show for the first time in 40 years. Thanks to Bill LaPointe and Jim King for attending the show for me and exhibiting the decoys. There is absolutely no way I could have pulled this together without family and friends. If I may use a baseball analogy, it really came down to the last of the ninth, two outs and the count at three and two before we managed to scratch out a hit and round out the offerings. -

1850 Pro Tiller

1850 Pro Tiller Specs Colors GENERAL 1850 PRO TILLER STANDARD Overall Length 18' 6" 5.64 m Summit White base w/Black Metallic accent & Tan interior Boat/Motor/Trailer Length 21' 5" 6.53 m Summit White base w/Blue Flame Boat/Motor/Trailer Width 8' 6" 2.59 m Metallic accent & Tan interior Summit White base w/Red Flame Boat/Motor/Trailer Height 5' 10" 1.78 m Metallic accent & Tan interior Beam 94'' 239 cm Summit White base w/Storm Blue Metallic accent & Tan interior Chine width 78'' 198 cm Summit White base w/Silver Metallic Max. Depth 41'' 104 cm accent & Gray interior Max cockpit depth 22" 56 cm Silver Metallic base w/Black Metallic accent & Gray interior Transom Height 25'' 64 cm Silver Metallic base w/Blue Flame Deadrise 12° Metallic accent & Gray interior Weight (Boat only, dry) 1,375# 624 kg Silver Metallic base w/Red Flame Metallic accent & Gray interior Max. Weight Capacity 1,650# 749 kg Silver Metallic base w/Storm Blue Max. Person Weight Capacity 6 Metallic accent & Gray interior Max. HP Capacity 90 Fuel Capacity 32 gal. 122 L OPTIONAL Mad Fish graphics HULL Shock Effect Wrap Aluminum gauge bottom 0.100" Aluminum gauge sides 0.090'' Aluminum gauge transom 0.125'' Features CONSOLE/INSTRUMENTATION Command console, w/lockable storage & electronics compartment, w/pull-out tray, lockable storage drawer, tackle storage, drink holders (2), gauges, rocker switches & 12V power outlet Fuel gauge Tachometer & voltmeter standard w/pre-rig Master power switch Horn FLOORING Carpet, 16 oz. marine-grade, w/Limited Lifetime Warranty treated panel -

An Orientation for Getting a Navy 44 Underway

Departure and return procedure for the Navy 44 • Once again, the Boat Information Book for the United States Naval Academy Navy 44 Sailing Training Craft is the final authority. • Please do not change this presentation without my permission. • Please do not duplicate and distribute this presentation without the permission of the Naval Academy Sailing Training Officer • Comments welcomed!! “Welcome aboard crew. Tami, you have the helm. If you’d be so kind, take us out.” When we came aboard, we all pitched in to ready the boat to sail. We all knew what to do and we went to work. • The VHF was tuned to 82A and the speakers were set to “both”. • The engine log book & hernia box were retrieved from the Cutter Shed. • The halyards were brought back to the bail at the base of the mast, but we left the dockside spinnaker halyard firmly tensioned on deck so boarding crew could use it to aid boarding. • The sail and wheel covers were removed and stored below. • The reef lines were attached and laid out on deck. • The five winch handles were placed in their proper holders. • The engine was checked: fuel level, fuel lines open, bilge level/condition, alternator belt tension, antifreeze level, oil and transmission level, RACOR filter, raw water intake set in the flow position, engine hours. This was all entered into the log book. • Sails were inventoried. We use the PESO system. We store sails in the forward compartment with port even, starboard odd. •The AC main was de-energized at the circuit panel. -

Sea Kayak Handling Sample Chapter

10 STERN RUDDERS Stern rudders are used to keep the kayak going in a straight line and make small directional changes when on the move. The stern rudder only works if the kayak is travelling at a reasonable speed, but it has many applications. The most common is when there is a following wind or sea pushing the kayak along at speed. In this situation, forward sweep strokes are not quick enough to have as much effect as the stern rudder. A similar application is when controlling the kayak while surfi ng. A more ‘gentle’ application is when moving in and out of rocks, caves and arches at slower speeds. Here, the stern rudder provides control and keeps the kayak on course in these tight spaces. Low angle stern rudder This is the classic stern rudder and works well to keep the kayak running in a straight line. It is best combined with the push/pull method of turning with a stern rudder (see below). • The kayak must be moving at a reasonable speed. • Fully rotate the body so that both hands are out over the side. • Keep looking forwards. • Place the blade nearest the stern of the kayak in the water as far back as your rotation allows. • The blade face should be parallel to the side of the kayak so that it cuts through the water and you feel no resistance. 54 • The blade should be fully submerged and will act like a rudder, controlling the direction of the kayak. • The front hand should be across the kayak and at a height between your stomach and chest. -

The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland

The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland Bruce F. Thompson Principal Investigator Maryland Department of Planning Maryland Historical Trust, Office of Archeology Maryland State Historic Preservation Office 100 Community Place Crownsville, Maryland 21032-2023 November, 2005 This project was accomplished through a partnership between the following organizations: Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Department of Natural Resources Martinak State Park Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Maritime Archaeological and Historical Society *The cover photo shows the entrance to Watts Creek where the Martinak Boat was discovered just to the right of the ramp http://www.riverheritage.org/riverguide/Sites/html/watts_creek.html (accessed December 10, 2004). Executive Summary The 1960s discovery and recovery of wooden shipwreck remains from Watt’s Creek, Caroline County induced three decades of discussion, study and documentation to determine the wrecks true place within the region’s history. Early interpretations of the wreck timbers claimed the vessel was an example of a Pungy (generally accepted to have been built ca. 1840 – 1920, perhaps as early as 1820), with "…full flaring bow, long lean run, sharp floors, flush deck…and a raking stem post and stern post" (Burgess, 1975:58). However, the closer inspection described in this report found that the floors are flatter and the stem post and stern post display a much longer run (not so raking as first thought). Additional factors, such as fastener types, construction details and tool marks offer evidence for a vessel built earlier than 1820, possibly a link between the late 18th-century shipbuilding tradition and the 19th-century Pungy form. The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland Introduction In November, 1989 Maryland Maritime Archeology Program (MMAP) staff met with Richard Dodds, then curator of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM), and Norman H. -

1Ba704, a NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE in the MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN and MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION, THE PEOPLE OF AFRICATOWN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY AND THE SLAVE WRECKS PROJECT PREPARED BY SEARCH INC. MAY 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION 468 SOUTH PERRY STREET PO BOX 300900 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 PREPARED BY ______________________________ JAMES P. DELGADO, PHD, RPA SEARCH PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY DEBORAH E. MARX, MA, RPA KYLE LENT, MA, RPA JOSEPH GRINNAN, MA, RPA ALEXANDER J. DECARO, MA, RPA SEARCH INC. WWW.SEARCHINC.COM MAY 2019 SEARCH May 2019 Archaeological Investigations of 1Ba704, A Nineteenth-Century Shipwreck Site in the Mobile River Final Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Between December 12 and 15, 2018, and on January 28, 2019, a SEARCH Inc. (SEARCH) team of archaeologists composed of Joseph Grinnan, MA, Kyle Lent, MA, Deborah Marx, MA, Alexander DeCaro, MA, and Raymond Tubby, MA, and directed by James P. Delgado, PhD, examined and documented 1Ba704, a submerged cultural resource in a section of the Mobile River, in Baldwin County, Alabama. The team conducted current investigation at the request of and under the supervision of Alabama Historical Commission (AHC); Alabama State Archaeologist, Stacye Hathorn of AHC monitored the project. This work builds upon two earlier field projects. The first, in March 2018, assessed the Twelvemile Wreck Site (1Ba694), and the second, in July 2018, was a comprehensive remote-sensing survey and subsequent diver investigations of the east channel of a portion the Mobile River (Delgado et al. -

Commercial Fishing Guide |

Texas Commercial Fishing regulations summary 2021 2022 SEPTEMBER 1, 2021 – AUGUST 31, 2022 Subject to updates by Texas Legislature or Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission TEXAS COMMERCIAL FISHING REGULATIONS SUMMARY This publication is a summary of current regulations that govern commercial fishing, meaning any activity involving taking or handling fresh or saltwater aquatic products for pay or for barter, sale or exchange. Recreational fishing regulations can be found at OutdoorAnnual.com or on the mobile app (download available at OutdoorAnnual.com). LIMITED-ENTRY AND BUYBACK PROGRAMS .......................................................................... 3 COMMERCIAL FISHERMAN LICENSE TYPES ........................................................................... 3 COMMERCIAL FISHING BOAT LICENSE TYPES ........................................................................ 6 BAIT DEALER LICENSE TYPES LICENCIAS PARA VENDER CARNADA .................................................................................... 7 WHOLESALE, RETAIL AND OTHER BUSINESS LICENSES AND PERMITS LICENCIAS Y PERMISOS COMERCIALES PARA NEGOCIOS MAYORISTAS Y MINORISTAS .......... 8 NONGAME FRESHWATER FISH (PERMIT) PERMISO PARA PESCADOS NO DEPORTIVOS EN AGUA DULCE ................................................ 12 BUYING AND SELLING AQUATIC PRODUCTS TAKEN FROM PUBLIC WATERS ............................. 13 FRESHWATER FISH ................................................................................................... 13 SALTWATER FISH ..................................................................................................... -

Boat Handling

Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary Search & Rescue Crew Manual BOAT 6 HANDLING The skills involved in handling a vessel are learned over time and come with practice. A new boat handler will fair better if they un- derstand and can apply some of the princi- ples and basic tools outlined in this chapter. “The difference between a rough docking and a smooth easy docking is around 900 attempts.” BOAT HANDLING CONTENTS 6.0 Introduction . .101 6.1 Helm Position . .101 6.2 Forces on Your Vessel . .103 6.2.1 Winds . .103 6.2.2 Waves . .103 6.2.3 Current . .104 6.2.4 Combined natural forces . .104 6.3 Vessel Characteristics . .104 6.3.1 Displacement Hulls . .104 6.3.2 Planing Hulls . .105 6.4 Propulsion and Steering . .107 6.4.1 Pivot Point . .108 6.4.2 Trim . .108 6.5 Propellers . .109 6.5.1 Parts of a Propeller . .109 6.6 Basic Manoeuvres . .110 6.7 Manoeuvring . .110 6.7.1 Directed Thrust . .110 6.7.2 Twin Engine Directed Thrust . .110 6.7.3 Waterjets . .112 6.7.4 Non-Directed Thrust and Rudder Deflection . .112 6.8 Getting Underway . .113 6.9 Approaching the Dock . .113 6.10 Station Keeping . .114 100 Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary Search & Rescue Crew Manual Excerpts taken from the book “High Seas High Risk” Written by Pat Wastel Norris 1999 (The Sudbury II was a legendary offshore salvage tug that had taken a large oil drilling platform in tow during the summer of 1961. This drama occurred in the Caribbean as Hurricane Hattie approached.) The Offshore 55, a towering oil rig, was at that time the largest rig in the world. -

United States National Museum

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 2 30 WASHINGTON, D.C. 1964 MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard I. Chapelle Curator of Transportation SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1964 — Publications of the United States National Aiuseum The scholarly and scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series the Museum publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of its constituent museums—The Museum of Natural History and the Museum of History and Technology setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of Anthropology, Biology, History, Geology, and Technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries, to cultural and scientific organizations, and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers from the Museum of Natural History. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902 papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum of Natural History have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions Jrom the United States National Herbarium, and since 1959, in Bulletins titled "Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology," have been gathered shorter papers relating to the collections and research of that Museum. -

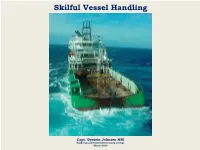

Skilful Vessel Handling

Skilful Vessel Handling Capt. Øystein Johnsen MNI Buskerud and Vestfold University College March 2014 Manoeuvring of vessels that are held back by an external force This consideration is written in belated wisdom according to the accident of Bourbon Dolphin in April 2007 When manoeuvring a vessel that are held back by an external force and makes little or no speed through the water, the propulsion propellers run up to the maximum, and the highest sideways force might be required against wind, waves and current. The vessel is held back by 1 800 meters of chain and wire, weight of 300 tons. 35 knops wind from SW, waves about 6 meter and 3 knops current heading NE has taken her 840 meters to the east (stb), out of the required line of bearing for the anchor. Bourbon Dolphin running her last anchor. The picture is taken 37 minutes before capsizing. The slip streams tells us that all thrusters are in use and the rudders are set to port. (Photo: Sean Dickson) 2 Lack of form stability I Emil Aall Dahle It is Aall Dahle’s opinion that the whole fleet of AHT/AHTS’s is a misconstruction because the vessels are based on the concept of a supplyship (PSV). The wide open after deck makes the vessels very vulnerable when tilted. When an ordinary vessel are listing an increasingly amount of volume of air filled hull is forced down into the water and create buoyancy – an up righting (rectification) force which counteract the list. Aall Dahle has a doctorate in marine hydrodynamics, has been senior principle engineer in NMD and DNV. -

Vol. 21, No. 10 October 2017 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 21, No. 10 October 2017 You Can’t Buy It Joseph Erb (Cherokee), Petition, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 36 inches Roy Bonney, Jr., Dogenvsv Degogigielv. Degogikahvsv. Noquu Otsilugi., acrylic on wood panel, 48 x 48 inches Images are from the exhibition Return from Exile: Contemporary Southeastern Indian Art, curated by Tony A. Tiger, Bobby C. Martin, and Jace Weaver, on view through December 8, 2017 at the Fine Art Museum, Fine & Performing Arts Center, Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, NC. The exhibition features more than thirty contemporary Southeastern Native American artists working in a variety of media including painting, drawing, printmaking, basketry, sculpture, and pottery. See the article on page 29. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, NC Page 3 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art CRAIG NELSON Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - Nance Lee Sneddon Page 4 - Editorial Commentary, Corrigan Gallery, Ann Long Fine Art & Fabulon Page 5 - Fabulon Art Page 5 - City of North Charleston, College of Charleston & Charleston Artist Guild Page 6 - Karen Burnette Garner & Halsey-McCallum Studios Page 6 - Angline Smith Fine Art, Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art, Meyer Vogl Gallery & Page 7 - Call for Lowcountry Ceramic Artists, Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Life Celebrations October 6th - October 31st, 2017 Folly Beach Arts & Crafts Guild Helena Fox Fine Art, Spencer Art Galleries, The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary, Page 8 - Meyer Vogl Gallery cont., Edward Dare Gallery , Fabulon cont.