From Imagined to Actual Perpetrator: Folman in Waltz with Bashir (Dir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Animation! [Page 8–9] 772535 293004 the TOWER 9> Playing in the Online Dark](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9735/animation-page-8-9-772535-293004-the-tower-9-playing-in-the-online-dark-289735.webp)

Animation! [Page 8–9] 772535 293004 the TOWER 9> Playing in the Online Dark

9 euro | SPRING 2020 MODERN TIMES REVIEW THE EUROPEAN DOCUMENTARY MAGAZINE CPH:DOX THESSALONIKI DF ONE WORLD CINÉMA DU RÉEL Copenhagen, Denmark Thessaloniki, Greece Prague, Czech Paris, France Intellectually stimulating and emotionally engaging? [page 10–11] THE PAINTER AND THE THIEF THE PAINTER HUMAN IDFF MAJORDOCS BOOKS PHOTOGRAPHY Oslo, Norway Palma, Mallorca New Big Tech, New Left Cinema The Self Portrait; Dear Mr. Picasso Animation! [page 8–9] 772535 293004 THE TOWER 9> Playing in the online dark In its more halcyon early days, nature of these interactions. ABUSE: In a radical the internet was welcomed Still, the messages and shared psychosocial experiment, into households for its utopi- (albeit blurred for us) images an possibilities. A constantly are highly disturbing, the bra- the scope of online updating trove of searchable zenness and sheer volume of child abuse in the Czech information made bound en- the approaches enough to sha- Republic is uncovered. cyclopaedia sets all but obso- ke anyone’s trust in basic hu- lete; email and social media manity to the core («potential- BY CARMEN GRAY promised to connect citizens ly triggering» is a word applied of the world, no longer seg- to films liberally these days, Caught in the Net mented into tribes by physical but if any film warrants it, it is distance, in greater cultural un- surely this one). Director Vit Klusák, Barbora derstanding. The make-up artist recog- Chalupová In the rush of enthusiasm, nises one of the men and is Czech Republic, Slovakia the old truth was suspended, chilled to witness this behav- that tools are only as enlight- iour from someone she knows, ened as their users. -

Regione Autonoma Valle D'aosta

PANO RAMI QUES VALLE d’AOSTA - VALLéE d’AOSTE Periodico semestrale - Sped. in a.p. - art. comma 20/c legge 662/96 - Filiale di Aosta - Tassa riscossa / Taxe perçue / Taxe riscossa - Tassa legge 662/96 - Filiale di Aosta - Sped. in a.p. art. comma 20/c Periodico semestrale Alejandro Fernandez Almendras + Cinema Yu-Chieh Cheng in valle d’aosta Tizza Covi e Rainer Frimmel Hippolyte Girardot et Nobuhiro Suwa + Focus sul documentario Måns Månsson valdostano 48 Avi Mograbi Marilia Rocha + Joseph Péaquin: II semestre 2009 Adrian Sitaru ritratto di un cineasta Rivista di cinema edita dall’assessoRato istRuzione e cultuRa della Regione autonoma valle d’aosta E éDITORIAL La Valle d’Aosta avrà una sua Film Commission Fra la Valle d’Aosta e il cinema esi- anni di diverse manifestazioni ci- ha seguito l’evoluzione del cine- ste quello che si dice un rapporto nematografiche, che punteggiano ma attraverso i film e la parola dei consolidato. La nostra regione non con il loro programmi il calendario; loro autori. Oggi questa pubblica- è stata soltanto il set di molti film non solo la Saison Culturelle con zione dell’Assessorato Istruzione del passato (dalle avventure del ra- le proiezioni del Giro del mondo, e Cultura della Regione autonoma gionier Fantozzi, a commedie come ma anche festival che toccano di- Valle d'Aosta si presenta in veste Tutta colpa del Paradiso di France- versi argomenti: il Noir in Festival rinnovata e accresciuta, attraverso sco Nuti, a film d’autore come Le e il genere poliziesco, il Cervino una nuova immagine grafica, il pas- acrobate di Silvio Soldini), ma, tra- Film Festival e il film di montagna, saggio dal bianco e nero al colore e mite l’avviamento dell’iter che con- Strade del Cinema e i classici del uno spazio dedicato alle cronache durrà alla costituzione di una Film cinema muto musicati dal vivo, lo cinematografiche della Valle. -

Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Theater Honors Papers Theater Department 2014 Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gordon, Julian, "Medea of Gaza" (2014). Theater Honors Papers. 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theater Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theater Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. GORDON !1 ! ! Medea of Gaza ! Julian Blake Gordon Spring 2014 MEDEA OF GAZA GORDON !1 GORDON !2 Research Summary A snapshot of Medea of Gaza as of March 7, 2014 ! Since the Summer of 2013, I’ve been working on a currently untitled play inspired by the Diane Arnson Svarlien translation of Euripides’ Medea. The origin of the idea was my Theater and Culture class with Nancy Hoffman, taken in the Spring of 2013. For our midterm, we were assigned to pick a play we had read and set it in a new location. It was the morning of my 21st birthday, a Friday, and the day I was heading home for Spring Break. My birthday falls on a Saturday this year, but tomorrow marks the anniversary, I’d say. I had to catch a train around 7:30am. The only midterm I hadn’t completed was the aforementioned Theater and Culture assignment. -

Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film and the Return to Right Now

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now Aaron Pellerin Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pellerin, Aaron, "Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2333. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2333 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. EVERYDAY TRANSCENDENCE: CONTEMPORARY ART FILM AND THE RETURN TO RIGHT NOW by AARON PELLERIN DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film and Media Studies) Approved By: _________________________________________ Advisor Date _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY AARON PELLERIN 2019 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Sue, who always sees the magic in the everyday. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I‘d like to thank my committee, and in particular my advisor, Dr. Steve Shaviro. His encouragement, his insightful critiques, and his early advice to just write were all instrumental in making this work what it is. I likewise wish to thank Dr. Scott Richmond for the time and energy he put in as I struggled through the middle stages of the degree. I am also grateful for a series of challenging and exciting seminars I took with Steve, Scott, and also with Dr. -

THE ESSAY FILM Minghella Building L University of Reading 30 April – 2 May 2015

CFAC – Centre for Film Aesthetics and Cultures FTT – Department of Film, Theatre & Television Conference WORLD CINEMA AND THE ESSAY FILM Minghella Building l University of Reading 30 April – 2 May 2015 WORLD CINEMA AND THE ESSAY FILM Conference Programme Instructions for Speakers and Panel Chairs Speakers Please keep your presentation to 20 minutes, including clips, to give adequate time for other speakers. Please check your technology in advance, during the break before your panel. It is sensible to bring a backup copy of your presentation and clips on a thumb drive. Questions will be taken once the speakers have all presented. Panel Chairs Please give your panel speakers signals for 5 minutes left and when 20 minutes are up. Panel chairs are invited to say a few words in response to the panel papers. The format of your response is completely flexible, although you might like to point any links or contrasts between the papers, and your own perspective on the issues raised. DAY 1: Thursday, 30 April 16:00 – 17:00 REGISTRATION 17:00 – 20:00 WELCOME ADDRESS by conference convenor Dr Igor Krstic SCREENING and Q & A Walter Salles in conversation with Prof Lúcia Nagib on the essay film, accompanied by a screening of one of his films DAY 2: Friday, 1 May 2015 TIME BULMERSHE THEATRE BOB KAYLEY THEATRE 9:00 – REGISTRATION 9:30 9:30 – Panel 1 (chaired by James Rattee) Panel 2 (chaired by Antonia 11:00 Memory & Trauma I Kazakopoulou) Bohr: ‘No Man’s Zone: The Essay Film in Debating Authorship the Aftermath of Fukushima’ Brunow: ‘Conceptualising -

RFC's Library's Book Guide

RFC’s Library’s Book Guide 2017 Since the beginning of our journey at the Royal Film Commission – Jordan (RFC), we have been keen to provide everything that promotes cinema culture in Jordan; hence, the Film Library was established at the RFC’s Film House in Jabal Amman. The Film Library offers access to a wide and valuable variety of Jordanian, Arab and International movies: the “must see” movies for any cinephile. There are some 2000 titles available from 59 countries. In addition, the Film Library has 2500 books related to various aspects of the audiovisual field. These books tackle artistic, technical, theoretical and historical aspects of cinema and filmmaking. The collec- tion of books is bilingual (English and Arabic). Visitors can watch movies using the private viewing stations available and read books or consult periodi- cals in a calm and relaxed atmosphere. Library members are, in addition, allowed to borrow films and/or books. Membership fees: 20 JOD per year; 10 JOD for students. Working hours: The Film Library is open on weekdays from 9:00 AM until 8:00 PM. From 3:00 PM until 8:00 PM on Saturdays. It is closed on Fridays. RFC’s Library’s Book Guide 2 About People In Cinema 1 A Double Life: George Cukor Patrick McGilligan 2 A Hitchcock Reader Marshall Dentelbaum & Leland Poague 3 A life Elia Kazan 4 A Man With a Camera Nestor Almenros 5 Abbas Kiarostami Saeed-Vafa & Rosenbaum 6 About John Ford Lindsay Anderson 7 Adventures with D.W. Griffith Karl Brown 8 Alexander Dovzhenko Marco Carynnk 9 All About Almodovar Epps And Kakoudeki -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Image to Infinity: Rethinking Description and Detail in the Cinema

IMAGE TO INFINITY: RETHINKING DESCRIPTION AND DETAIL IN THE CINEMA by Alison L. Patterson BS, University of Pittsburgh, 1997 MA, Cinema Studies New York University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical and Cultural Studies University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alison L. Patterson It was defended on February 23, 2011 and approved by Troy Boone, PhD, Associate Professor, English Adam Lowenstein, PhD, Associate Professor, English Colin MacCabe, PhD, Distinguished University Professor, English Randall Halle, PhD, Klaus W. Jonas Professor of German and Film Studies Dissertation Director: Marcia Landy, PhD, Distinguished Professor, English ii Copyright © Alison L. Patterson 2011 All Rights Reserved iii IMAGE TO INFINITY: RETHINKING DESCRIPTION AND DETAIL IN THE CINEMA Alison L. Patterson, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 In the late 1980s, historian Hayden White suggested the possibility of forms of historical thought unique to filmed history. White proposed the study of “historiophoty,” an imagistic alternative to written history. Subsequently, much scholarly attention has been paid to the category of History Film. Yet popular concerns for historical re‐presentation and heritage have not fully addressed aesthetic effects of prior history films and emergent imagistic‐historiographic practices. This dissertation identifies and elaborates one such alternative historiographic practice on film, via inter‐medial study attending to British and American history films, an instance of multi‐platform digital historiography, and an animated film – a category of film often overlooked in history film studies. -

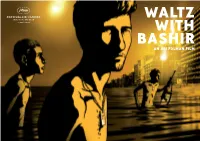

Waltz with Bashir

waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 1 WALTZ WITH BASHIR AN ARI FOLMAN FILM waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 2 waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 3 SYNOPSIS One night at a bar, an old friend tells director Ari about a recurring nightmare in which he is chased by 26 vicious dogs. Every night, the same number of beasts. The two men conclude that there’s a connection to their Israeli Army mission in the first Lebanon War of the early eighties. Ari is surprised that he can’t remember a thing anymore about that period of his life. Intrigued by this riddle, he decides to meet and interview old friends and comrades around the world. He needs to discover the truth about that time and about himself. As Ari delves deeper and deeper into the mystery, his memory begins to creep up in surreal images … waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 4 INTERVIEW WITH ARI FOLMAN Did you start this project as an animated documentary? Yes indeed. WALTZ WITH BASHIR was always meant to be an animated documentary. For a few years, I had the basic idea for the film in my mind but I was not happy at all to do it in real life video. How would that have looked like? A middleaged man being interviewed against a black background, telling stories that happened 25 years ago, without any archival footage to support them. That would have been SO BORING! Then I figured out it could be done only in animation with fantastic drawings. -

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021 2 The School of Visual Arts has been authorized by the Association, Inc., and as such meets the Education New York State Board of Regents (www.highered.nysed. Standards of the art therapy profession. gov) to confer the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts on graduates of programs in Advertising; Animation; The School of Visual Arts does not discriminate on the Cartooning; Computer Art, Computer Animation and basis of gender, race, color, creed, disability, age, sexual Visual Effects; Design; Film; Fine Arts; Illustration; orientation, marital status, national origin or other legally Interior Design; Photography and Video; Visual and protected statuses. Critical Studies; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts on graduates of programs in Art Education; The College reserves the right to make changes from Curatorial Practice; Design Research, Writing and time to time affecting policies, fees, curricula and other Criticism; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts in matters announced in this or any other publication. Teaching on graduates of the program in Art Education; Statements in this and other publications do not and to confer the degree of Master of Fine Arts on grad- constitute a contract. uates of programs in Art Practice; Computer Arts; Design; Design for Social Innovation; Fine Arts; Volume XCVIII number 3, August 1, 2021 Illustration as Visual Essay; Interaction Design; Published by the Visual Arts Press, Ltd., © 2021 Photography, Video and Related Media; Products of Design; Social Documentary Film; Visual Narrative; and to confer the degree of Master of Professional Studies credits on graduates of programs in Art Therapy; Branding; Executive creative director: Anthony P. -

Memorias Del Club De Cine: Más Allá De La Pantalla 2008-2015

Memorias del Club de Cine: Más allá de la pantalla 2008-2015 MAURICIO LAURENS UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Decanatura Cultural © 2016, UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Calle 12 n.º 1-17 Este, Bogotá Tel. (57 1) 342 0288 [email protected] www.uexternado.edu.co ISSN 2145 9827 Primera edición: octubre del 2016 Diseño de cubierta: Departamento de Publicaciones Composición: Precolombi EU-David Reyes Impresión y encuadernación: Digiprint Editores S.A.S. Tiraje de 1 a 1.200 ejemplares Impreso en Colombia Printed in Colombia Cuadernos culturales n.º 9 Universidad Externado de Colombia Juan Carlos Henao Rector Miguel Méndez Camacho Decano Cultural 7 CONTENIDO Prólogo (1) Más allá de la pantalla –y de su pedagogía– Hugo Chaparro Valderrama 15 Prólogo (2) El cine, una experiencia estética como mediación pedagógica Luz Marina Pava 19 Metodología y presentación 25 Convenciones 29 CUADERNOS CULTURALES N.º 9 8 CAPÍTULOS SEMESTRALES: 2008 - 2015 I. RELATOS NUEVOS Rupturas narrativas 31 I.1 El espejo - I.2 El diablo probablemente - I.3 Padre Padrone - I.4 Vacas - I.5 Escenas frente al mar - I.6 El almuerzo desnudo - I.7 La ciudad de los niños perdidos - I.8 Autopista perdida - I.9 El gran Lebowski - I.10 Japón - I.11 Elephant - I.12 Café y cigarrillos - I.13 2046: los secretos del amor - I.14 Whisky - I.15 Luces al atardecer. II. DEL LIBRO A LA PANTALLA Adaptaciones escénicas y literarias 55 II.1 La bestia humana - II.2 Hamlet - II.3 Trono de sangre (Macbeth) - II.4 El Decamerón - II.5 Muerte en Venecia - II.6 Atrapado sin salida - II.7 El resplandor - II.8 Cóndores no entierran todos los días - II.9 Habitación con vista - II.10 La casa de los espíritus - II.11 Retrato de una dama - II.12 Letras prohibidas - II.13 Las horas. -

IB FILM SL & HL Year 1 Mr. London SUMMER READING

IB FILM SL & HL year 1 Mr. London SUMMER READING & VIEWING WHAT YOU WILL NEED: ● Either a public library card (FREE)/a Netflix, Hulu, or FilmStruck account ($7.99 - $11 month - but usually these services offer a free trial!) ● Internet access ● A journal/notebook for jotting down observations ● Mr. London’s email: o [email protected] REQUIREMENTS (to be completed by the first day of class in August): 1) Select 10 films from the list provided (though watch as many as you can!). You MUST watch 1 film from each of the categories, and the rest is your choice. 2) Write a response (1-2 pages each) for each film. a. If you have access to a computer/laptop, you may type up your responses in a continuing Google document, 12 point Open Sans, and double-spaced (to be shared with me by the first day of class). b. Each film’s response should be in paragraph form and should be about your observations, insights, comments, and connections that you are making between the readings and the films you watch. c. Also, your responses will be much richer if you research information about the films you watch before you write – simply stating your opinion will not give you much material to write about, and you will not be able to go beyond your own opinion – for example, read online articles/reviews about each film by scholars/critics (New York Times, The Guardian, rogerebert.com, IMDB.com, filmsite.org, etc). You can also watch awesome video essays on YouTube. Click HERE for a great list of YouTube Channels.