Anthropos Redux: a Defence of Monism in the Anthropocene Epoch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversation with Rosi Braidotti 27/01/16 11:33

Conversation with Rosi Braidotti 27/01/16 11:33 nYwebsite en tijdschrift voor literatuur, kritiek & amusement, voorheen yang & freespace Nieuwzuid Nieuwste nummer > Transitzone/ RosiConversation Braidotti, Sarah Posman with Rosi Braidotti Published: 19/06/2013 Tags: litcrit interview philosophy psychoanalysis Sarah Posman (nY) in conversation with Rosi Braidotti on contemporary feminism and amor fati, in March 2012. Sarah Posman: In Metamorphosis: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming you write that “time is on our side.” Do you still feel that way in the light of the present moments of crisis that we’re witnessing in society and academia – the lack of funding for Women’s Studies departments in the low countries is an urgent example. When there is revolt against these developments – the riots in cities across Europe, the academe-affiliated Occupy movements – it doesn’t seem to come in the Dionysian guise you promote. Rosi Braidotti: The phrase “time is on our side” is grounded both in an intellectual and institutional practice of feminism. For me feminist theory is transformative. This implies a debate with gender and gender mainstreaming, which is one of the great growth areas not only of the academe but of our society, and an area that will produce a great deal of employment for our students. Gender mainstreaming is egalitarian and terribly important. I support it completely, but it is not transformative, necessarily. I was watching TV last night, on the eve of international women’s day, and all the major international networks were doing features on the status of women. Al Jazeera had a wonderful set of interviews about women in the Arab world and women entrepreneurs in India. -

Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman

17 Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman The Alpha Course, a well‐known evangelical Christian programme, advertises itself with posters displaying the words THE MEANING OF LIFE IS_________, followed by the invitation ‘Fill in the blanks at alpha.org’. Followers of the course will discover that ‘Men and women were created to live in a relationship with God’, and that ‘without that relationship there will always be a hunger, an emptiness, a feeling that something is missing’.1 We all have that need because we are all sinners, we are told, and the truth which will fill the need is that Jesus Christ died to save us from our sins. Not all Christian or other religious views about the meaning of life are as simplistic as this, but they typically share the assumptions that the meaning of life is to be found in some belief whose truth we need to recognize, and that this is a belief about the purpose for which we exist. A further implication is that this purpose is the purpose intended by the God who created us, and that if we fail to identify and live in accordance with that purpose, our lives will lack meaning. The assumption is echoed in the question many humanists will have encountered: if you don’t believe in a God, what’s the point of it all? And many people who don’t share the answer still accept the legitimacy of the question – ‘What is the meaning of life?’ – and assume that what we need is a correct belief, religious or non‐religious, which will fill the blank in the sentence ‘The meaning of life is …’. -

History and Theory of Philosophy

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "BASHKIR STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (FSBEI HE BSMU MOH Russia) HISTORY AND THEORY OF PHILOSOPHY Textbook Ufa 2020 1 UDC 1(09)(075.8) BBC 87.3я7 H90 Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the department «Social work» FSBEI HE «Bashkir State University» U.S. Vildanov Doctor of Philosophy, Professor at the Department of Philosophy and History FSBEIHE «Bashkir State Agricultural University» A.I. Stoletov History and theory of philosophy:textbook/ K.V. Khramova, H90 R.I. Devyatkina, Z.R. Sadikova, O.M. Ivanova, O.G. Afanasyeva, A.S. Zubairova-Valeeva, N.R. Mingazova, G.R. Davletshina — Ufa: Ufa: FSBEIHEBSMUMOHRussia, 2020. – 127 p. The manual was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Higher Education in specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine» the current curriculum and on the basis of the work program on the discipline of philosophy. The manual is focused on the competence-based learning model. It has an original, uniform for all classes structure, including the topic, a summary of the training questions, the subject of essays, training materials, test items with response standards, recommended literature. This manual covers topics related to the periods of development of world philosophy. Designed for students in the specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine». It is recommended to be published by the Coordinating Scientific and Methodological Council and was approved by the decision of the Editorial and Publishing Council of the BSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of Russia. -

Science, Reason, Knowledge, and Wisdom: a Critique of Specialism

Science, Reason, Knowledge, and Wisdom: A Critique of Specialism Nicholas Maxwell University College, London Published in Inquiry, vol. 23, 1980, pp. 19-81. In this paper I argue for a kind of intellectual inquiry which has, as its basic aim, to help all of us to resolve rationally the most important problems that we encounter in our lives, problems that arise as we seek to discover and achieve that which is of value in life. Rational problem-solving involves articulating our problems, proposing and criticizing possible solutions. It also involves breaking problems up into subordinate problems, creating a tradition of specialized problem-solving - specialized scientific, academic inquiry, in other words. It is vital, however, that specialized academic problem-solving be subordinated to discussion of our more fundamental problems of living. At present specialized academic inquiry is dissociated from problems of living - the sin of specialism, which I criticize. I In this paper I discuss two rival views about the nature of intellectual inquiry. I call these two views fundamentalism and specialism. I shall argue that at present the whole institutional structure of scientific, academic inquiry, by and large, presupposes specialism. Of the two views under consideration it is, however, fundamentalism, and not specialism, which provides us with a rational conception of intellectual inquiry. Failure to put fundamentalism into practice has profoundly damaging con-sequences for science and scholarship, and indeed for life, for our whole modern world. Ideally intellectual inquiry ought to help us to tackle rationally those problems of living which we encounter in seeking to discover and achieve that which is of value in life. -

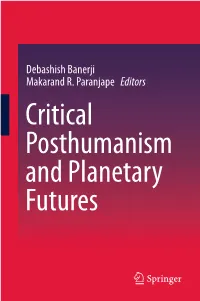

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

Writing As a Nomadic Subject

Comparative Critical Studies 11.2–3 (2014): 163–184 Edinburgh University Press DOI: 10.3366/ccs.2014.0122 C British Comparative Literature Association www.euppublishing.com/ccs Writing as a Nomadic Subject ROSI BRAIDOTTI I am rooted but I flow Virginia Woolf, The Waves1 My lifelong engagement in the project of nomadic subjectivity has been partly motivated by the conviction that, in these globalized times of accelerating technologically mediated changes, many traditional points of reference and age-old habits of thought are being re-composed, albeit in contradictory ways. Paradoxically, old power relations are not only confirmed but in many ways exacerbated in the new geo-political context.2 At such a time more conceptual creativity is necessary, and more theoretical courage is needed in order to bring about the leap across inertia, nostalgia, aporia and the other forms of critical stasis induced by our historical condition. It has become like a mantra to me: we need to learn to think differently about the kind of subjects we have already become and the processes of deep-seated transformation we are undergoing. The philosopher in me believes that a new alliance between philosophy, the arts and science is a crucial building block for this qualitative shift of perspective.3 The writer in me, on the other hand, continues to muse about the complex ways in which the imaginary both propels and resists in-depth transformations. A MATTER OF STYLE At the beginning of it all, for my generation, is the commitment to writing. Presented as a form of political and ethical engagement, it is essentially a visceral gesture. -

Philosophy and Life by Saad Malook

57 Al-Hikmat Volume 28 (2008), pp. 57-70 PHILOSOPHY AND LIFE SAAD MALOOK* Abstract. The paper presents the applications of philosophy to life. Philosophy has been serving the homo sapiens for thousands of years. It has been the queen of all sciences and was the cradle for entire human civilization. The topic, ‘Philosophy and Life’ is so extensive and rich in its nature that many volumes of books could be written but my purpose to write on this topic is to clear the misconceptions regarding philosophy and its significance to life, which are present among various circles in the present age. What is the nature of philosophy? How was it in the past? What is life? Has it meaning and purpose in this world? How does philosophy contribute for man today? How will it improve the quality of life of man in future? Which philosophy of life should man adopt to make this world a heaven? These are the questions, whose answers are tried to be sought out in this paper. Man’s impatient mind has ever been in search of the hidden realities in the microcosm (man) and the macrocosm (universe). The history of man reveals that he has contributed to the improve- ment of the world. Thales’ search for the ultimate substance made a start to the odyssey of philosophy, which journeyed through various trenches, uneven paths, faced numerous challenges from *Mr. Saad Malook is Lecturer at Department of Philosophy, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore-54590 (Pakistan). (E-mail: [email protected]) 58 S. -

Rosi Braidotti, the Posthuman

The Posthuman The Posthuman Rosi Braidotti polity Copyright © Rosi Braidotti 2013 The right of Rosi Braidotti to be identifi ed as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2013 by Polity Press Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4157-7 ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4158-4 (pb) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Group Limited, Bodmin, Cornwall The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. -

A Cartography of Angry Indian Goddesses Towards Nomadic Affect

Indi@logs Vol 7 2020, pp 11-25, ISSN: 2339-8523 DOI https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.150 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ A CARTOGRAPHY OF ANGRY INDIAN GODDESSES TOWARDS NOMADIC AFFECT INDRANI MUKHERJEE Jawaharlal Nehru University [email protected] Received: 31-10-2019 Accepted: 17-12-2019 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to draw a cartography of becoming Angry Indian Goddesses as transnational nomadism towards an embodied and material rethinking of women’s friendships from outside the constraints of systemic binaries. The friends are all professional women who are globally wired, whose thinking minds and non-docile bodies detach themselves from any normative modes of belonging in their respective personal and professional realms. They map a post-humanist spatiality of rhizomic linkages with other animate and non-animate entities, throwing up a new ethics of nomadic affect and responsibility. The film begins with a panoramic gaze of the Goan landscape, overlapped with flash images of Hindu goddesses and their animal escorts framed within a power packed song “Kattey”, which intersects Bhanwari Devi’s powerful folk composition of Meera Bai’s 15th century mystic tradition with Haard Kaur’s rap. The crossing of the song and the violent events of rejection that the women face, unbridle a becoming angry goddesses through a pastiche of the anxious goddesses and women sited on an axis of re/de-valorised difference. Goa becomes a potential third space entangled with all of the above, as it dwells on the contemplative scope of this cartography as redemptive and suggests a re-humanization of schizophrenic splintered objects through love and affect. -

Complete Issue

Center for Open Access in Science Open Journal for Studies in Philosophy 2019 ● Volume 3 ● Number 1 https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsp.0301 ISSN (Online) 2560-5380 OPEN JOURNAL FOR STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY (OJSP) ISSN (Online) 2560-5380 https://www.centerprode.com/ojsp.html [email protected] Publisher: Center for Open Access in Science (COAS) Belgrade, SERBIA https://www.centerprode.com [email protected] Editor-in-Chief: Tatyana Vasileva Petkova (PhD) South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Faculty of Philosophy, Blagoevgrad, BULGARIA Editorial Board: Jane Forsey (PhD) University of Winnipeg, Faculty of Arts, CANADA Cristóbal Friz Echeverria (PhD) University of Santiago de Chile, Faculty of Humanities, CHILE Plamen Makariev (PhD) Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Faculty of Philosophy, BULGARIA Antoaneta Nikolova (PhD) South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Faculty of Philosophy, Blagoevgrad, BULGARIA Adrian Nita (PhD) Romanian Academy, Institute of Philosophy and Psychology, Bucharest, ROMANIA Hasnije Ilazi (PhD) University of Prishtina, Faculty of Philosophy, KOSOVO Copy Editor: Goran Pešić Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade Open Journal for Studies in Philosophy, 2019, 3(1), 1-24. ISSN (Online) 2560-5380 __________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 1 Hellenistic Philosophy in Greek and Roman Times Ioanna-Soultana Kotsori 6 Pedagogical Views of Plato in his Dialogues Marina Nasaina 17 The Idea of Tolerance – John Locke and Immanuel Kant Tatyana Vasileva Petkova Open Journal for Studies -

Rudolf Eucken's Philsophy of Life

RUDOLF EUCKEN’S PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE BY W. R. BOYCE GIBSON LECTURER IN PHILOSOPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON LONDON ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1906 PREFACE T he chapters in this book were originally delivered as inter-collegiate lectures at Westfield College, Uni versity of London, during the Michaelmas term, 1905. They arose out of the deep respect I feel for the work and personality of Professor Eucken, and from a profound sense of the importance of his teaching for philosophy, for religion, and for everyday life. In the publication of these lectures I have been most generously assisted by the Hibbert Trustees. My sincerest thanks are due to them, not only for the grant defraying the expenses of publication, but for their sympathetic recognition of the value of Professor Eucken’s work, and of the need for making it better known to English readers. I gratefully acknowledge the help given me by my wife in the typing of the manuscript and the reading of the proofs. I am also most indebted in this connec tion to Professor Eucken himself, who very kindly read through all the proof-sheets, and assisted me in many ways with the most unfailing cordiality and goodwill. CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTORY— EUCKEN’S PHILOSOPHICAL PUBLICA TIONS— OUTLINE SKETCH OF THE NEW IDEALISM, WITH PRELIMINARY APPRECIATION AND CRITICISM— EUCKEN’S PHILOSOPHY A RALLYING-POINT FOR IDEALISTIC EFFORT— THE SOLIDARITY OF IDEALISM 1 -2 1 CHAPTER II e u c k e n ’s v i e w s o n t h e r e l a t i o n o f p h il o s o p h y t o HISTORY, PARTICULARLY TO THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY, -

Immanuel Kanfs Influence on the Psychology of Alfred Adler

Immanuel Kanfs Influence on the Psychology of Alfred Adler Mark H. Stone Abstract The influence of immanuel Kant's philosophy on the psychology of Alfred Adler is important to understand because Kant much earlier addressed many ideas and concepts assumed original with Adler. Kant addressed the concepts of private sense and common sense, the primacy of reason, the existential questions of life, fictions, the power ofthe mind over sense perceptions, the unconscious and conscious mind, unity of the person, fostering community feeling, and determining a moral course of action, all concepts Adler later applied to his psychology. Familiarity with Kant's works can help clinicians gain a better understanding of what Adler wrote and im- plied when explicating Individual Psychology. Kant's writings can be complicated and difficult to understand, but several very readable essays are recommended and readily available. The purpose of this article is to show the influence of Immanuel Kant's (1 724-1804) philosofjhy upon the psychology of Alfred Adler (1870-1937). A number of Adier's important ideas can be traced back to the writings of Kant. This is not to diminish Adier's contributions to psychology because it is Adier's elucidation of these concepts for understanding behavior that is striking. This connection between Kant and Adler relates a segment of the continuing stream of thought in intellectual history that connects the ideas from one thinker to those of another. Ellenberger (1970) wrote, "Adler has many affinities with Kant" (p. 628). However, Ellenberger stopped short of elucidating any of these connections save a very short discussion of com- mon sense and private sense.