Getting Beyond Religion As Science: "Unstifling" Worldview Formation in American Public Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part Four - 'Made in America: Christian Fundamentalism' Transcript

Part Four - 'Made in America: Christian Fundamentalism' Transcript Date: Wednesday, 10 November 2010 - 2:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 10 November 2010 Made in America Christian Fundamentalism Dr John A Dick Noam Chomsky: “We must bear in mind that the U.S. is a very fundamentalist society, perhaps more than any other society in the world – even more fundamentalist than Saudi Arabia or the Taliban. That's very surprising.” Overview: (1) Introduction (2) Five-stage evolution of fundamentalism in the United States (3) Features common to all fundamentalisms (4) What one does about fundamentalism INTRODUCTION: In 1980 the greatly respected American historian, George Marsden published Fundamentalism and American Culture, a history of the first decades of American fundamentalism. The book quickly rose to prominence, provoking new studies of American fundamentalism and contributing to a renewal of interest in American religious history. The book’s timing was fortunate, for it was published as a resurgent fundamentalism was becoming active in politics and society. The term “fundamentalism” was first applied in the 1920’s to Protestant movements in the United States that interpreted the Bible in an extreme and literal sense. In the United States, the term “fundamentalism” was first extended to other religious traditions around the time of the Iranian Revolution in 1978-79. In general all fundamentalist movements arise when traditional societies are forced to face a kind of social disintegration of their way of life, a loss of personal and group meaning and the introduction of new customs that lead to a loss of personal and group orientation. -

Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman

17 Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman The Alpha Course, a well‐known evangelical Christian programme, advertises itself with posters displaying the words THE MEANING OF LIFE IS_________, followed by the invitation ‘Fill in the blanks at alpha.org’. Followers of the course will discover that ‘Men and women were created to live in a relationship with God’, and that ‘without that relationship there will always be a hunger, an emptiness, a feeling that something is missing’.1 We all have that need because we are all sinners, we are told, and the truth which will fill the need is that Jesus Christ died to save us from our sins. Not all Christian or other religious views about the meaning of life are as simplistic as this, but they typically share the assumptions that the meaning of life is to be found in some belief whose truth we need to recognize, and that this is a belief about the purpose for which we exist. A further implication is that this purpose is the purpose intended by the God who created us, and that if we fail to identify and live in accordance with that purpose, our lives will lack meaning. The assumption is echoed in the question many humanists will have encountered: if you don’t believe in a God, what’s the point of it all? And many people who don’t share the answer still accept the legitimacy of the question – ‘What is the meaning of life?’ – and assume that what we need is a correct belief, religious or non‐religious, which will fill the blank in the sentence ‘The meaning of life is …’. -

Sociology of Religion, Lundscow, Chapter 7, Cults

Sociology of Religion , Sociology 3440-090 Summer 2014, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office Room 429 Beh. Sci., Office Hours: Thursday - Friday, Noon – 4:00-pm Office Phone: (801) 531-3075 Home Phone: (801) 278-6413 Email: [email protected] I. Goals: The primary goal of this class is to give students a sociological understanding of religion as a powerful, important, and influential social institution that is associated with many social processes and phenomena that motivate and influence how people act and see the world around them. The class will rely on a variety of methods that include comparative analysis, theoretical explanations, ethnographic studies, and empirical studies designed to help students better understand religion and its impact upon societies, global-international events, and personal well-being. This overview of the nature, functioning, and diversity of religious institutions should help students make more discerning decisions regarding cultural, political, and moral issues that are often influenced by religion. II. Topics To Be Covered: The course is laid out in two parts. The first section begins with a review of conventional and theoretical conceptions of religion and an overview of the importance and centrality of religion to human societies. It emphasizes the diversity and nature of "religious experience" in terms of different denominations, cultures, classes, and individuals. This is followed by overview of sociological assumptions and theories and their application to religion. A variety of theoretical schools including, functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory, sociology of knowledge, sociobiology, feminist theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodern and critical theory will be addressed and applied to religion. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

History and Theory of Philosophy

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "BASHKIR STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (FSBEI HE BSMU MOH Russia) HISTORY AND THEORY OF PHILOSOPHY Textbook Ufa 2020 1 UDC 1(09)(075.8) BBC 87.3я7 H90 Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the department «Social work» FSBEI HE «Bashkir State University» U.S. Vildanov Doctor of Philosophy, Professor at the Department of Philosophy and History FSBEIHE «Bashkir State Agricultural University» A.I. Stoletov History and theory of philosophy:textbook/ K.V. Khramova, H90 R.I. Devyatkina, Z.R. Sadikova, O.M. Ivanova, O.G. Afanasyeva, A.S. Zubairova-Valeeva, N.R. Mingazova, G.R. Davletshina — Ufa: Ufa: FSBEIHEBSMUMOHRussia, 2020. – 127 p. The manual was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Higher Education in specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine» the current curriculum and on the basis of the work program on the discipline of philosophy. The manual is focused on the competence-based learning model. It has an original, uniform for all classes structure, including the topic, a summary of the training questions, the subject of essays, training materials, test items with response standards, recommended literature. This manual covers topics related to the periods of development of world philosophy. Designed for students in the specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine». It is recommended to be published by the Coordinating Scientific and Methodological Council and was approved by the decision of the Editorial and Publishing Council of the BSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of Russia. -

The Art and Science of Framing an Issue

MAPThe Art and Science of Framing an Issue Authors Contributing Editors © January 2008, Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) and the Movement Advancement Project (MAP). All rights reserved. “Ideas are a medium of exchange and a mode of influence even more powerful than money, votes and guns. … Ideas are at the center of all political conflict.” —Deborah Stone, Policy Process Scholar, 2002 The Art and Science of 1 Framing an Issue an Issue and Science of Framing Art The The Battle Over Ideas 2 Understanding How People Think 2 What Is Framing? 4 Levels of Framing 5 Tying to Values 6 Why Should I Spend Resources on Framing? 6 How Do I Frame My Issue? 7 Step 1. Understand the Mindset of Your Target Audience 7 Step 2. Know When Your Current Frames Aren’t Working 7 Step 3. Know the Elements of a Frame 7 Step 4. Speak to People’s Core Values 9 Step 5. Avoid Using Opponents’ Frames, Even to Dispute Them 9 Step 6. Keep Your Tone Reasonable 10 Step 7. Avoid Partisan Cues 10 Step 8. Build a New Frame 10 Step 9. Stick With Your Message 11 “Ideas are a medium of exchange and a mode of influence even more powerful than money, votes and guns. … Ideas are at the center of all political conflict.” —Deborah Stone, Policy Process Scholar, 2002 2 The Battle Over Ideas Are we exploring for oil that’s desperately needed to drive our economy and sustain our nation? Or are we Think back to when you were 10 years old, staring at destroying delicate ecological systems and natural your dinner plate, empty except for a pile of soggy– lands that are a legacy to our grandchildren? These looking green vegetables. -

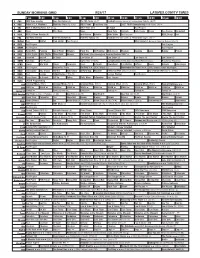

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Psychology, Meaning Making and the Study of Worldviews: Beyond Religion and Non-Religion

Psychology, Meaning Making and the Study of Worldviews: Beyond Religion and Non-Religion Ann Taves, University of California, Santa Barbara Egil Asprem, Stockholm University Elliott Ihm, University of California, Santa Barbara Abstract: To get beyond the solely negative identities signaled by atheism and agnosticism, we have to conceptualize an object of study that includes religions and non-religions. We advocate a shift from “religions” to “worldviews” and define worldviews in terms of the human ability to ask and reflect on “big questions” ([BQs], e.g., what exists? how should we live?). From a worldviews perspective, atheism, agnosticism, and theism are competing claims about one feature of reality and can be combined with various answers to the BQs to generate a wide range of worldviews. To lay a foundation for the multidisciplinary study of worldviews that includes psychology and other sciences, we ground them in humans’ evolved world-making capacities. Conceptualizing worldviews in this way allows us to identify, refine, and connect concepts that are appropriate to different levels of analysis. We argue that the language of enacted and articulated worldviews (for humans) and worldmaking and ways of life (for humans and other animals) is appropriate at the level of persons or organisms and the language of sense making, schemas, and meaning frameworks is appropriate at the cognitive level (for humans and other animals). Viewing the meaning making processes that enable humans to generate worldviews from an evolutionary perspective allows us to raise news questions for psychology with particular relevance for the study of nonreligious worldviews. Keywords: worldviews, meaning making, religion, nonreligion Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Raymond F. -

Science, Reason, Knowledge, and Wisdom: a Critique of Specialism

Science, Reason, Knowledge, and Wisdom: A Critique of Specialism Nicholas Maxwell University College, London Published in Inquiry, vol. 23, 1980, pp. 19-81. In this paper I argue for a kind of intellectual inquiry which has, as its basic aim, to help all of us to resolve rationally the most important problems that we encounter in our lives, problems that arise as we seek to discover and achieve that which is of value in life. Rational problem-solving involves articulating our problems, proposing and criticizing possible solutions. It also involves breaking problems up into subordinate problems, creating a tradition of specialized problem-solving - specialized scientific, academic inquiry, in other words. It is vital, however, that specialized academic problem-solving be subordinated to discussion of our more fundamental problems of living. At present specialized academic inquiry is dissociated from problems of living - the sin of specialism, which I criticize. I In this paper I discuss two rival views about the nature of intellectual inquiry. I call these two views fundamentalism and specialism. I shall argue that at present the whole institutional structure of scientific, academic inquiry, by and large, presupposes specialism. Of the two views under consideration it is, however, fundamentalism, and not specialism, which provides us with a rational conception of intellectual inquiry. Failure to put fundamentalism into practice has profoundly damaging con-sequences for science and scholarship, and indeed for life, for our whole modern world. Ideally intellectual inquiry ought to help us to tackle rationally those problems of living which we encounter in seeking to discover and achieve that which is of value in life. -

How Our Worldviews Shape Our Practice

How Our Worldviews Shape Our Practice Rachel M. Goldberg This article reviews research on the effect of a conflict resolution practi- tioner’s worldview on practice. The results revealed patterns connecting worldview frames with differing uses of power. Forty-three environ- mental and intercultural practitioners were interviewed, and narrative and metaphor analysis was used to reveal key worldview orientations in their practice stories. The results are correlated in continuums and “pro- files” of the worldview orientation. The findings strengthen previous work questioning the effects of the traditional neutrality stance, deepen fieldwide arguments for the embedded nature of worldview and cul- ture, and describe new methods that reveal some of the dynamics between worldview and practice. Native American tribe spent many years struggling against a govern- Ament agency for permanent residence status on their traditional homeland (the ability to live in and use their traditional homeland). Over time, their argument became a fight about permanent homes, because this was the only way to argue for use of the land that the agency understood. For the agency representatives, permanent housing (a building) was syn- onymous with permanent residence (ability to live on and use the land). One day, the mediator who was working with the tribe asked them why they wanted permanent homes. It turned out that the area became very hot during the summer; the tribe had traditionally built temporary homes in the winter and migrated to the mountains during the hot season. It become clear that the tribe did not even really want permanent housing, but a right to reside legally in the area—in their case, a very different goal. -

Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 83 Issue 1 2005 Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution Matthew J. Brauer Princeton University Barbara Forrest Southeastern Louisiana University Steven G. Gey Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Religion Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew J. Brauer, Barbara Forrest, and Steven G. Gey, Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution, 83 WASH. U. L. Q. 1 (2005). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Quarterly VOLUME 83 NUMBER 1 2005 IS IT SCIENCE YET?: INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONISM AND THE CONSTITUTION MATTHEW J. BRAUER BARBARA FORREST STEVEN G. GEY* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................