Leatherhead & District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document: D-26817DDE 00001

The Holme, Clay Lane, Headley, Surrey. KT18 6JS £1,500,000 Freehold • Living Room & Separate Family Room • Family Bathroom • Open Plan Kitchen/Dining Room • SW Facing flint wall Formal Garden • Rear Lobby/Boot Room & Utility Room • Oak Framed Carport & Adjoining Garage • Downstairs Bed 5/Study with e/s Shower Room • Equestrian Opportunity 1-3 Church Street, Leatherhead, • Master Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom • Three Paddocks extending to Approx. 3 Acres Surrey KT22 8DN • 3 Further Bedrooms • Scope to extend (subject to Planning) 01372 360078 [email protected] www.patrickgardner.com The Holme A charming detached Victorian House occupying a plot of just over 4.5 acres This property also benefits from mains drains and mains gas which is unusual in including three paddocks (of approximately 3 acres) on the edge of this sought Headley. after Surrey Village and offering a rare family equestrian opportunity. This attractive detached late Victorian house was built, we believe, in Council Tax Band H approximately 1890 and is well presented by its current owners. EPC Rating F The property enjoys attractive elevations and is approached via a long private driveway with electric remote controlled gates and is set on its plot in such a way that it enjoys a high degree of privacy. The total land holding comprises paddocks, a small wooded area and formal part flint wall enclosed gardens which enjoy a sunny south westerly aspect. The light and airy accommodation includes a wealth of original features including a Reception Hall, spacious double aspect Living Room, Family Room, Kitchen/Dining Room with adjoining Utility Room and large walk-in larder, rear Lobby/Boot Room and a Ground Floor 5th Bedroom/study with En Suite Shower Room. -

21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

21 bus time schedule & line map 21 Crawley - Dorking - Leatherhead - Epsom View In Website Mode The 21 bus line (Crawley - Dorking - Leatherhead - Epsom) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Box Hill: 7:08 PM (2) Crawley: 6:51 AM - 5:15 PM (3) Epsom: 6:20 AM - 2:46 PM (4) Leatherhead: 5:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 21 bus arriving. Direction: Box Hill 21 bus Time Schedule 19 stops Box Hill Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:08 PM Leatherhead Railway Station (T) Station Approach, Leatherhead Tuesday 7:08 PM Leret Way, Leatherhead Wednesday 7:08 PM Leret Way, Leatherhead Thursday 7:08 PM The Crescent, Leatherhead Friday 7:08 PM Russell Court, Leatherhead Saturday Not Operational Highlands Road, Leatherhead Seeability, Leatherhead Lavender Close, Leatherhead 21 bus Info Clinton Road, Leatherhead Direction: Box Hill Stops: 19 Glenheadon Rise, Leatherhead Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Leatherhead Railway Station (T), Tyrrells Wood, Leatherhead Leret Way, Leatherhead, The Crescent, Leatherhead, Highlands Road, Leatherhead, Seeability, Headley Court, Headley Leatherhead, Clinton Road, Leatherhead, Glenheadon Rise, Leatherhead, Tyrrells Wood, Hurst Lane, Headley Leatherhead, Headley Court, Headley, Hurst Lane, Headley, The Cock Inn, Headley, Broome Close, The Cock Inn, Headley Headley, Crossroads, Headley, Headley Common Road, Headley, Headley Common Road, Broome Close, Headley Pebblecombe, The Tree, Box Hill, -

Mole Valley District Council Register of Enforcement and Stop Notices and Other Enforcement Action

Mole Valley District Council Register of Enforcement and Stop Notices and other Enforcement Action Enforcement Location Type of Summary of Alleged Breach Authorised Effective Compliance Enforcement Location Ref Notice Date Date Due Date Ref 2001/001/ENF Colinholme, Boxhill Enforcement Without planning permission, the change of use of that part of 15-May-2001 26-Jun-2001 25-Mar-2002 Road, Boxhill, Tadworth, Notice the land shown hatched black on the attached plan to a use for Enforcement Surrey, KT20 7PN the stationing of a mobile home for residential occupation Details separate from the main dwelling on the land 2001/002/ENF Welling Barn Farm, Russ Enforcement Without planning permission, the change of use of the 22-Jan-2001 05-Mar-2001 04-Jul-2001 26-Feb-2001 Hill, Charlwood, Horley, Notice buildings within the area coloured blue on the attached plan Enforcement Surrey, RH6 0EL from agricultural to non-agricultural storage. Details 2001/003/ENF Myrtle Cottage, Norwood Enforcement Without plannng permission, the erection of an extension 25-Sep-2001 12-Dec-2001 11-Jun-2002 Hill, Charlwood, Horley, Notice between the dwellinghouse, and an outbuilding on the land in Enforcement Surrey, RH6 0ET the position shown on the attached plan. Details 2001/004/ENF Ricketts Wood Farm, Enforcement Without planning permission, the change of use of the land 14-Sep-2001 26-Oct-2001 23-Nov-2001 Norwood Hill, Notice from a mixed use comprising agriculture, residential and the Enforcement Charlwood, Horley, parking of not more than 200 motor vehicles to a use Details Surrey, RH6 0ET comprising agriculture, residential and the parking of motor vehicles in excess of 200 in number. -

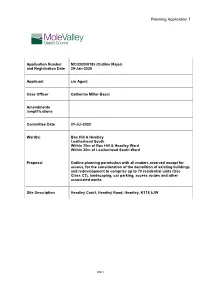

Planning Application 1

Planning Application 1 Application Number MO/2020/0185 (Outline Major) and Registration Date 29-Jan-2020 Applicant c/o Agent Case Officer Catherine Miller-Bassi Amendments /amplifications Committee Date 01-Jul-2020 Ward(s) Box Hill & Headley Leatherhead South Within 20m of Box Hill & Headley Ward Within 20m of Leatherhead South Ward Proposal Outline planning permission with all matters reserved except for access, for the consideration of the demolition of existing buildings and redevelopment to comprise up to 70 residential units (Use Class C3), landscaping, car parking, access routes and other associated works Site Description Headley Court, Headley Road, Headley, KT18 6JW DM 1 RECOMMENDATION: Approve subject to conditions 1. Summary The application is to be decided by the Planning Committee because it exceeds the threshold set within the consitution. The application is in outline only with all matters reserved except for access. The reserved matters for consideration in principle only at this stage include the demolition of existing buildings and areas of hardstanding, and the redevelopment of the site comprising the erection of up to 70no. new dwellings, landscaping, car parking, access routes and other associated works. The key drawings under consideration include the Access Parameters Plan and the Land Use Parameters Plan, which has been submitted to inform the assessment of the principle of the erection of the proposed new dwellings and the site redevelopment, particularly with regard to Green Belt policy. The Illustrative Site Layout Plan is not for approval in this case as the detailed layout falls under reserved matters. The application site, of approx. 7ha., lies to the north and south sides of The Drive, on the west of Headley Road, adjacent the Grade II Listed Headley Court house and grounds, and 0.7miles to the north-east of Headley Village. -

SGT Newsletter September 2018 Draft 2 Pdf Copy

NEWSLETTER September 2018 No. 53 Jekyll Digitisation Evening Autumn Lecture Project Update with Richard Bisgrove Gertrude Jekyll: Artist, Gardener, Craftswoman Wednesday 3 October, 7 for 7.30pm We had a wonderful response to our Open Garden Event on 1 July. A huge thank you to all members who came along on a hot summer's day to support. We raised £1,500 on the day and with donations made following our wider appeal and publicity we met our target of £4,000. The work to copy digitally Gertrude Jekyll’s drawings and papers held at UC, Berkeley, is well underway and due to be completed by 31 December 2018. A huge thank you to Michael Edwards for initiating and working so hard on this [email protected] project. We are hugely grateful to the support of Surrey Bees, Toast, Marina Bisgrove is an accomplished lecturer and has Christopher of Phoenix Perennial Plants, Taurus Wines, and local sculptor written seven books on aspects of garden David Paynter, all of whom joined us on the day. We also had wonderful design and garden history, including The raffle prizes donated by Squires Garden Centre, Loseley House, West National Trust Book of the English Garden and Dean College, the Grange Festival, Hampshire and Grange Park Opera, The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll. His latest book, West Horsley, Ros Wallinger of Upton Grey, Riverford Organic Farmers, Gardening across the Pond was released in the Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden and Cherfold Cottage Flowers of September 2018. He is a consultant on the Chiddingfold as well as many private donations. -

Surrey County Council A4 Portrait Timetable

Epsom - Leatherhead - Boxhill - Dorking 516 Buses Excetera Timetable effective 20 January 2014 Monday to Friday Days SDO SH Epsom, Kiln Lane Sainsburys ... 0910 1110 1210 1310 1410 1505 1510 1705 ... Epsom, High Street ... 0915 1115 1215 1315 1415 1510 1515 1715 ... Epsom Hospital ... 0918 1118 1218 1318 1418 1513 1518 1718 ... Ashtead, The Street ... 0925 1125 1225 1325 1425 1522w 1525 1725 ... Leatherhead, Railway Station 0728 \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ... Leatherhead, The Crescent 0732 0932 1132 1232 1332 1432 1542 1532 1732 1832 Leatherhead, Seeability 0735 0935 1135 1235 1335 1435 1545 1535 1735 1835 Headley Court 0742 0942 1142 1242 1342 1442 1552 1542 1742 1842 Headley Church 0744 0944 1144 1244 1344 1444 1554 1544 1744 1844 Box Hill, Upper Farm 0752 0952 1152 1252 1352 1452 1602 1552 1752r 1852r Box Hill NT East Car Park 0755 0955 1155 1255 1355 1455 1605 1555 1755r 1855r Pebblecombe, Pebblehill Road 0803 1003 1203 1303 1403 1503 1613 1603 ... ... Brockham, Brockham Lane 0809 1009 1209 1309 1409 1509 1619 1609 ... ... Pixham Lane, Chester Close 0812 1012 1212 1312 1412 1512 1622 1612 ... ... London Road, Dorking Railway Station 0815 1015 1215 1315 1415 1515 1625 1615 ... ... Dorking, White Horse 0818 1018 1218 1318 1418 1518 1628 1618 ... ... Dorking, South Street 0820t 1020 1220 1320 1420 1520 1630 1620 ... ... Code SDO - Schooldays only r - Continues on request of passengers on board w - Operates via All Saints Church for Therfield School at 1532 SH - School Holidays t - Continues to Townfield Court for The Priory School Saturday Epsom, Kiln Lane Sainsburys 0910 1110 1310 1510 1705 Epsom, High Street 0915 1115 1315 1515 1715 Epsom Hospital 0918 1118 1318 1518 1718 Ashtead, The Street 0925 1125 1325 1525 1725 Leatherhead, The Crescent 0932 1132 1332 1532 1732 Leatherhead, Seeability 0935 1135 1335 1535 1735 Headley Court 0942 1142 1342 1542 1742 Headley Church 0944 1144 1344 1544 1744 Box Hill, Upper Farm 0952 1152 1352 1552 1752r Box Hill NT East Car Park 0955 1155 1355 1555 1755r Pebblecombe, Pebblehill Road 1003 1203 1403 1603 .. -

The Parish of St. Martin's Dorking with St. Mary's Pixham Annual Report

The Parish of St. Martin’s Dorking with St. Mary’s Pixham Annual Report 2017 Annual Parochial Church Meeting Sunday 29th April 2018 Registered Charity 1133695 APCM 2018 Reports Page 1 of 20 Achievements and performance The Thanksgiving Service on September 29th to mark • Completely rebuilt our website in a new style Mole Valley’s farewell to the Defence Services more easily navigated on modern devices and Medical Rehabilitation Centre at Headley Court, for continued to grow our social media presence as which we were honoured to be visited by HRH evidenced by Twitter followers; Countess of Wessex, was a reminder of the things • Carried out further work (thanks to the Friends which St Martin’s as an important town centre of St Martin’s) to restore the decoration in the church does exceptionally well. But it is also a Chancel of St Martin’s; also redecoration of the reminder of the challenge we face in ensuring we parish room at St Mary’s Pixham which has seen a have a sufficient core of active membership to make very welcome upturn in wider community use. those big set piece occasions feasible. A similar picture emerges from the contrast between our very One completely new initiative planned at the back small but loyal Sunday morning choir and the choir end of 2017 and launched in January 2018 has been a for the Nine Lessons and Carols, for example, or a new monthly café-style 4pm family service in cathedral visit, when we call on additional resources collaboration with St Paul’s Dorking and St John’s in the shape, mainly, of previous choristers who have North Holmwood. -

Functional and Mental Health Status of United Kingdom Military Amputees Postrehabilitation

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation journal homepage: www.archives-pmr.org Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2015;96:2048-54 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Functional and Mental Health Status of United Kingdom Military Amputees Postrehabilitation Peter Ladlow, MSc,a,b Rhodri Phillip, MSc, FRCP,a John Etherington, MSc, FRCP,a Russell Coppack, MSc,a James Bilzon, PhD,b M. Polly McGuigan, PhD,b Alexander N. Bennett, PhD, FRCPa From the aAcademic Department of Military Rehabilitation, Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre (DMRC) Headley Court, Headley, Epsom, Surrey; and bDepartment for Health, University of Bath, Bath, UK. Abstract Objectives: To evaluate the functional and mental health status of severely injured traumatic amputees from the United Kingdom military at the completion of their rehabilitation pathway and to compare these data with the published normative data. Design: Retrospective independent group comparison of descriptive rehabilitation data recorded postrehabilitation. Setting: A military complex trauma rehabilitation center. Participants: Amputees (NZ65; mean age, 29Æ6y) were evaluated at the completion of their rehabilitation pathway; of these, 54 were operationally (combat) injured (23 unilateral, 23 bilateral, 8 triple) and 11 nonoperationally injured (all unilateral). Interventions: Continuous w4-week inpatient, physician-led, interdisciplinary rehabilitation followed by w4-weeks of patient-led, home-based rehabilitation. Main Outcome Measures: The New Injury Severity Score at the point of injury was used as the baseline reference. The 6-minute walk test, Amputee Mobility Predictor with Prosthesis, Special Interest Group in Amputee Medicine, Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre mobility and activity of daily living scores as well as depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), anxiety (General Anxiety Disorder Scale-7), mental health support, and pain scores were recorded at discharge and compared with the published normative data. -

Maps Archive Part 2

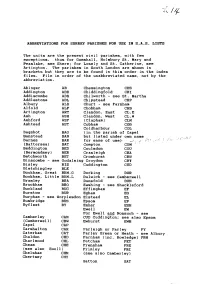

ABBREVIATIONS F O R S U R R E Y P A R I S H E S F O R U S E I N S . A . S . L I S T S T h e u n i t s a r e the present civil parishes. with few exceptions. t h u s f o r G o m s h a l l , H o l m b u r y S t . M a r y a n d Peaslake, see Shere; for L o s e l y a n d S t . C a t h e r i n e , s e e Artington. The parishes in South London are shown in b r a c k e t s b u t t h e y a r e t o be found in thisi o r d e r i n t h e i n d e x files. File in o r d e r o f t h e u n a b b r e v i a t e d n a m e , n o t b y t h e abbreviat ion. Ab i nger AB Chessington CHS Addington ADD Chiddingfold CHI Add i scombe ADS C h i l w o r t h - s e e St. Martha Addlestone ADL Chipstead CHP A1bury ALB C h u r t - s e e F a r n h a m Alfold ALF Chobham CHB Artington ART Clandon, East CL.E Ash ASH Clandon, West CL.W Ashford ASF (Clapham) CLM Ashtead AST Cobham COB Coldharbour COL Bagshot BAG (in the parish of Capel Banstead BAN but listed under own name Barnes BAR f o r e a s e o f u s e > (Battersea) BAT Compton COM Beddington BED Cou1sdon COU (Bermondsey) BER Cranleigh CRA Betchworth BET Crowhurst CRW B i n s c o m b e - s e e Godalming Croydon CRY Bisley BIS Cuddington CUD Bletchingley BLE Bookham, Great BKM.G Dorking DOR Bookham, Little BKM.L D u l w i c h - s e e C a m b e r w e l 1 Bramley BRA Dunsfold DUN Brockham BRO E a s h i n g - s e e S h a c k l e f o r d Buckland BUC Effingham EF Burstow BUR Egham EG B u r p h a m - s e e Worplesdon Elstead EL Busbridge BUS Epsom EP Byfleet BY Esher ESH Ewel 1 EW F o r E w e l l a n d N o n s u c h - s e e Camberley CAM CUD Cuddington; see also Epsom (Camberwel1) CBW Ewhurst EWH Capel CAP Carshalton CAR F a r l e i g h o r F a r l e y F Y Caterharo CAT F a r l e y G r e e n o r H e a t h - s e e A l b u r y Chaldon CHD F a r n h a m ( i n c . -

Newsletter September 2019 .Pub

Leatherhead & District Local History Society covering Ashtead, the Bookhams, Fetcham, Headley, Mickleham and Leatherhead Newsletter September 2019 Headley Court, the Jacobean-style Grade 2 listed former home of the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre near Leatherhead (shown above), was sold last year. Developer Angle Property has been holding consultations this summer on how best to use the 82-acre site while safeguarding the mansion and lessening the destructive impact on the Green Belt. See story on Page 32. Above and right: Two works by local artist Anthony Hill in the current Museum exhibition. Go to Page 8 for information. Corporate Member: 58 The Street, Ashtead INDEX TO ARTICLES Title Page Editorial 3 Chairman’s Report 4 News from the Friends of the Museum 5 Programme of Activities 7 Retrospective Exhibition: The Works of Anthony Hill 8 Lecture Report: The Use of LIDAR in Archaeology 11 Bookham Village Day 14 Oral History Feature: Jean Elizabeth Hutchinson 15 Feature: Donald Campbell in Leatherhead 18 Feature: Owners of the Leatherhead Tan Mill 22 Feature: The Sad Tale of Albert Powell 26 Ashtead’s Oldest AA Telephone Box? 30 Research Call: Who Exactly was Arthur Bird? 31 Feature: What future for Headley Court? 32 Obituary: Dr Derek Renn 34 Fetcham’s Rising Sun 37 Officers of the Society 38 Vacancies 40 Advert: Dorking Concertgoers 40 The revised National Planning Policy Framework (Feb 2019) provides government guidance to local planning authorities and defines heritage assets as: ‘A building, monument, site, place, or landscape identified as having a degree of significance meriting consideration in planning decisions because of its heritage interest.’ These include sites recognised as important locally and not only those with statutory designations. -

Autumn CONTENTS

60p DORKING ANGLICANS AND METHODISTS TOGETHER September 2020 with St Mary’s, Pixham & St Barnabas, Ranmore Autumn CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2020 Number 491 1 Autumn 2 This Page! Contents 3 Reflection for September by The Revd Stuart Peace and 4 Reflection for September contd. and APCM 2020 - Sunday 13th September, 11 am 5 Eco Church - Bronze Award 6 Why is that there? 7 News from the Belfry for September 8 Chaplain’s Corner for September 9 Chaplain’s Corner contd. and Christian Centre Notice 10 Hymn of the Month, There’s a wideness in God’s mercy The editorial team is always open to ideas for improvements 11 Hymn of the Month contd. and some poems to your magazine. Feedback from 12 An Interview with the Bunns readers suggests that, for a publication of this type, articles 13 He has made everything beautiful in its time should normally be no longer 14 Extract from the Bishop of Guildford’s Sermon, ‘So why do than one page, i.e. a maximum of you people need so many crisps?’ 730 words. Please bear this in mind when submitting copy. 15 Bishop of Guildford’s Sermon contd. Suitable photographs are always 16 Dorking Museum in September welcome. 17 Dorking Museum contd. 18 Effingham to Ephesus - tales from a sabbatical Editorial policy 19 Do you remember when ……..? The Editor, consulting the Magazine Committee, reserves 20 One of Many Farewells the right not to publish any 21 The Towers of Trebizond. (extract) article which is deemed 22 Adverts unsuitable for any reason, but our intention remains to include 23 Activities and Useful Phone Numbers contributions from across a 24 Who’s Who at St Martin’s, St Mary’s & St Barnabas broad theological spectrum (and also on other matters of SUBSCRIPTIONS for St Martin’s Magazine community interest). -

Burford Body Wordsearch

APRIL 2021 ISSUE 44 AI RPI LO T INSIDE AGM ELECTIONS AND REPORT WORKING WITH COVID FLYING COVID FREE DIARY THE HONOURABLE COMPANY All physical events have been postponed until further OF AIR PILOTS notice. Some meetings will take place through video- conferencing. For the latest situation please visit the incorporating Air Navigators calendar page of the Company’s website: https://www.airpilots.org/members-pages/company-calendar/ PATRON: His Royal Highness The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT Guidelines for submissions to Air Pilot Please submit contributions as follows: GRAND MASTER: • Text in word document, including your name below the His Royal Highness title of the piece; The Prince Andrew • No embedded photos; Duke of York KG GCVO • All images to be sent as jpeg files with a file size of at least 2 MB; MASTER: • More than 2 images to be sent via a Dropbox file, Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) rather than an e-mail attachment. CLERK: Paul J Tacon BA FCIS Incorporated by Royal Charter. A Livery Company of the City of London. PUBLISHED BY: The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Access the Company’s website Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN via this QR code, EMAIL : [email protected] www.airpilots.org EDITOR: Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] DEPUTY EDITOR: Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] or follow us on Twitter @AirPlotsCo EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the June 2021 edition of Air Pilot is 1 st May 2021. FUNCTION PHOTOGRAPHY: Gerald Sharp Photography View images and order prints on-line.