Douala As a “Hybrid Space” : Comparing Online and Offline Representations of a Sub-Saharan City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infrastructure Causes of Road Accidents on the Yaounde – Douala Highway, Cameroon

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of Development Research ISSN: 2230-9926 Vol. 10, Issue, 06, pp. 36260-36266, June, 2020 https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.18747.06.2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS INFRASTRUCTURE CAUSES OF ROAD ACCIDENTS ON THE YAOUNDE – DOUALA HIGHWAY, CAMEROON 1WOUNBA Jean François, 2NKENG George ELAMBO and *3MADOM DE TAMO Morrelle 1Department of Town Planning, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon; 2Director of the National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon: 3Department of Civil Engineering, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT ArticleArticle History: History: The overall goal of this study was to determine the causes of road crashes related to road th ReceivedReceived 24xxxxxx, March, 2019 2020 infrastructure parameters on the National Road No. 3 (N3) and provide measures to improve the ReceivedReceived inin revisedrevised formform safety of all road users. To achieve this, 225 accident reports for the years 2017 and 2018 were th 19xxxxxxxx, April, 2020 2019 th collected from the State Defense Secretariat. This accident data was analyzed using the crash AcceptedAccepted 20xxxxxxxxx May, 2020, 20 19 frequency and the injury severity density criteria to obtain the accident-prone locations (7 critical Published online 25th June, 2020 Published online xxxxx, 2019 sections and 2 critical intersections) and a map presenting these locations produced with ArcGis Key Words: 10.4.1. A site visit of these locations was then performed to obtain the road infrastructure and environment data necessary to get which parameters are responsible for road crashes. -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Report on the IDB2014 Celebrations in Cameroon

CAMEROON CELEBRATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL DAY FOR BIODIVERSITY Yaounde, Cameroon 14 May 2014 THEME: ISLAND BIODIVERSITY REPORT A cross-section of the exhibition ground including school children and the media Yaounde, 15 May 2014 1 CITATION This document will be cited as MINEPDED 2014. Report on the Celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity in Cameroon ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The organisation of the 2014 Day for Biodiversity was carried out under the supervision of the Minister of Environment, Protection of Nature and Sustainable Development Mr HELE Pierre and the Minister Delegate Mr. NANA Aboubacar DJALLOH. The contributions of the Organising Committee were highly invaluable for the success of the celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity. Members were: AKWA Patrick- Secretary General of MINEPDED- Representative of the Minister at the celebration; GALEGA Prudence- National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity- coordinator of the celebration; WADOU Angele- Sub-Director of Biodiversity and Biosafety, MINEPDED; WAYANG Raphael- Chief of Service for Biodiversity, MINEPDED NFOR Lilian- Environmental Lawyer at the Service of the Technical Adviser No1 of MINEPDED; SHEI Wilson- Project Assistant, ABS; NDIFOR Roland -Representative of IUCN- Cameroon; BANSEKA Hycinth- Representative of Global Water Partnership- Cameroon MBE TAWE Alex- Representative of World Fish Centre- Cameroon 2 TABLE of CONTENT Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………....4 Preparatory activities………………………………………………………………………..5 Media activities………………………………………………………………………………….5 Commemoration of activities…………………………………………………………….6 Exhibition………………………………………………………………………………………....7 Presentation of stands……………………………………………………………………….7 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………12 Photo gallery…………………………………………………………………………………….13 3 INTRODUCTION Cameroon as a member of the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity joined the international community to celebrate the International Day for Biodiversity 2014 under the theme ‘Island Biodiversity”. -

Cameroon Page 1 of 19

Cameroon Page 1 of 19 Cameroon Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 Cameroon is a republic dominated by a strong presidency. Despite the country's multiparty system of government, the Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) has remained in power since the early years of independence. In October, CPDM leader Paul Biya won re-election as President. The primary opposition parties fielded candidates; however, the election was flawed by irregularities, particularly in the voter registration process. The President retains the power to control legislation or to rule by decree. He has used his legislative control to change the Constitution and extend the term lengths of the presidency. The judiciary was subject to significant executive influence and suffered from corruption and inefficiency. The national police (DGSN), the National Intelligence Service (DGRE), the Gendarmerie, the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Military Security, the army, the civilian Minister of Defense, the civilian head of police, and, to a lesser extent, the Presidential Guard are responsible for internal security; the DGSN and Gendarmerie have primary responsibility for law enforcement. The Ministry of Defense, including the Gendarmerie, DGSN, and DRGE, are under an office of the Presidency, resulting in strong presidential control of internal security forces. Although civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, there were frequent instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of government authority. Members of the security forces continued to commit numerous serious human rights abuses. The majority of the population of approximately 16.3 million resided in rural areas; agriculture accounted for 24 percent of gross domestic product. -

Pdf | 300.72 Kb

Report Multi-Sector Rapid Assessment in the West and Littoral Regions Format Cameroon, 25-29 September 2018 1. GENERAL OVERVIEW a) Background What? The humanitarian crisis affecting the North-West and the South-West Regions has a growing impact in the bordering regions of West and Littoral. Since April 2018, there has been a proliferation of non-state armed groups (NSAG) and intensification of confrontations between NSAG and the state armed forces. As of 1st October, an estimated 350,000 people are displaced 246,000 in the South-West and 104,000 in the North-West; with a potential increment due to escalation in hostilities. Why? An increasing number of families are leaving these regions to take refuge in Littoral and the West Regions following disruption of livelihoods and agricultural activities. Children are particularly affected due to destruction or closure of schools and the “No School” policy ordered by NSAG since 2016. The situation has considerably evolved in the past three months because of: i) the anticipated security flashpoints (the start of the school year, the “October 1st anniversary” and the elections); ii) the increasing restriction of movement (curfew extended in the North-West, “No Movement Policy” issued by non-state actors; and iii) increase in both official and informal checkpoints. Consequently, there has been a major increase in the number of people leaving the two regions to seek safety and/or to access economic and educational opportunities. Preliminary findings indicate that IDPs are facing similar difficulties and humanitarian needs than the one reported in the North-West and the South-West regions following the multisectoral needs assessment done in March 2018. -

In Southwest and Littoral Regions of Cameroon

UNIVERSITY OF BUEA FACULTY OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES MARKETS AND MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS FOR ERU (Gnetum spp.) IN SOUTH WEST AND LITTORAL REGIONS OF CAMEROON BY Ndumbe Njie Louis BSc. (Hons) Environmental Science A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Science of the University of Buea in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Natural Resources and Environmental Management July 2010 ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Almighty God who gave me the ability to carryout this project. To my late father Njie Mojemba Maximillian I and my beloved little son Njie Mojemba Maximillian II. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people: Dr A. F. Nkwatoh, of the University of Buea, for his supervision and guidance; Verina Ingram, of CIFOR, for her immense technical guidance, supervision and support; Abdon Awono, of CIFOR, for guidance and comments; Jolien Schure, of CIFOR, for her comments and field collaboration. I also wish to thank the following organisations: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the Commission des Forets d‟Afrique Centrale (COMIFAC) for the opportunity to work within their framework and for the team spirit and support. I am also very grateful to the following collaborators: Ewane Marcus of University of Buea; Ghislaine Bongers of Wageningen University, The Netherlands and Georges Nlend of University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland for their collaboration in the field. Thanks also to Agbor Demian of Mamfe. -

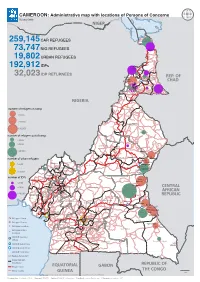

CAMEROON: Administrative Map with Locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad

CAMEROON: Administrative map with locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad 259,145 CAR REFUGEES Logone-Et-Chari 73,747 NIG REFUGEES Kousseri 19,802 URBAN REFUGEES Waza IDPs Limani 192,912 Magdeme Mora Mayo-Sava IDP RETURNEES Diamare 32,023 Mokolo REP. OF Gawar EXTREME-NORD Minawao Maroua CHAD Mayo-Tsanaga Mayo-Kani Mayo-Danay Mayo-Louti NIGERIA number of refugees in camp Benoue >5000 >15000 NORD Faro >20,000 Mayo-Rey number of refugees out of camp >3000 >5000 Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier >20,000 Vina Ndip Beka Borgop Nyambaka number of urban refugees ADAMAOUA Djohong Ngam Gbata Alhamdou Menchum Donga-Mantung >5000 Meiganga Mayo-Banyo Djerem Mbere Kounde Gadi Akwaya NORD-OUEST Gbatoua Boyo Bui Foulbe <10,000 Mbale Momo Mezam number of IDPs Ngo-ketunjia Manyu Gado Bamboutos Badzere <2000 Lebialem Noun Mifi Sodenou >5000 Menoua OUEST Mbam-et-Kim CENTRAL Hauts-Plateaux Lom-Et-Djerem Kupe-Manenguba Koung-Khi AFRICAN >20,000 Haut-Nkam SUD-OUEST Nde REPUBLIC Ndian Haute-Sanaga Mbam-et-Inoubou Moinam Meme CENTRE Timangolo Bertoua Bombe Sandji1 Nkam Batouri Pana Moungo Mbile Sandji2 Lolo Fako LITTORAL Lekie Kadei Douala Mefou-et-Afamba Mbombete Wouri Yola Refugee Camp Sanaga-Maritime Yaounde Mfoundi Nyong-et-Mfoumou EST Refugee Center Nyong-et-Kelle Mefou-et-Akono Ngari-singo Refugee Location Mboy Haut-Nyong Refugee Urban Nyong-et-So Location UNHCR Country Ocean Office Mvila SUD Dja-Et-Lobo Boumba-Et-Ngoko Bela UNHCR Sub-Office Libongo UNHCR Field Office Vallee-du-Ntem UNHCR Field Unit Region Boundary Departement boundary REPUBLIC OF Major roads EQUATORIAL GABON Minor roads THE CONGO GUINEA 50km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Cameroon: Administrative Map with Locations of Persons of Concerns; October 2016

CAMEROON: Administrative map with locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad 259,145 CAR REFUGEES Logone-Et-Chari 73,747 NIG REFUGEES Kousseri 19,802 URBAN REFUGEES Waza IDPs Limani 192,912 Magdeme Mora Mayo-Sava IDP RETURNEES Diamare 32,023 Mokolo REP. OF Gawar EXTREME-NORD Minawao Maroua CHAD Mayo-Tsanaga Mayo-Kani Mayo-Danay Mayo-Louti NIGERIA number of refugees in camp Benoue >5000 >15000 NORD Faro >20,000 Mayo-Rey number of refugees out of camp >3000 >5000 Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier >20,000 Vina Ndip Beka Borgop Nyambaka number of urban refugees ADAMAOUA Djohong Ngam Gbata Alhamdou Menchum Donga-Mantung >5000 Meiganga Mayo-Banyo Djerem Mbere Kounde Gadi Akwaya NORD-OUEST Gbatoua Boyo Bui Foulbe <10,000 Mbale Momo Mezam number of IDPs Ngo-ketunjia Manyu Gado Bamboutos Badzere <2000 Lebialem Noun Mifi Sodenou >5000 Menoua OUEST Mbam-et-Kim CENTRAL Hauts-Plateaux Lom-Et-Djerem Kupe-Manenguba Koung-Khi AFRICAN >20,000 Haut-Nkam SUD-OUEST Nde REPUBLIC Ndian Haute-Sanaga Mbam-et-Inoubou Moinam Meme CENTRE Timangolo Bertoua Bombe Sandji1 Nkam Batouri Pana Moungo Mbile Sandji2 Lolo Fako LITTORAL Lekie Kadei Douala Mefou-et-Afamba Mbombete Wouri Yola Refugee Camp Sanaga-Maritime Yaounde Mfoundi Nyong-et-Mfoumou EST Refugee Center Nyong-et-Kelle Mefou-et-Akono Ngari-singo Refugee Location Mboy Haut-Nyong Refugee Urban Nyong-et-So Location UNHCR Country Ocean Office Mvila SUD Dja-Et-Lobo Boumba-Et-Ngoko Bela UNHCR Sub-Office Libongo UNHCR Field Office Vallee-du-Ntem UNHCR Field Unit Region Boundary Departement boundary REPUBLIC OF Major roads EQUATORIAL GABON Minor roads THE CONGO GUINEA 50km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Rural Linkages in the City of Bamenda

By Vincent Nji Ndumu Mayor Bamenda City, Cameroon ❖ Bamenda is a cosmopolitan city and capital of the North West Region, Cameroon ❖ Its the 3rd largest city in Cameroon after Douala and Yaoundé, located 366kms north-west of the country’s capital, Yaoundé ❖ Its population is 600,000+ inhabitants over an area of 1076km2 with a density of 744persons/km2 ❖ It is a city council with three Sub-Divisional councils (Bamenda I, II, and III) ❖ Bamenda is a socio-economic, political and commercial hub for the region and also connects other major cities and towns to Nigeria Some outstanding actions strengthening urban – rural linkages in the city of Bamenda and the neighboring rural centers Road Infrastructure; ▪ Development and paving of 47.6km of roads linking the city to its periphery and neighboring rural centers ▪ Funded by the world bank, an ongoing construction of the dilapidated major highway into the city linking smaller towns and the Sub-Division of Santa (a major rural agricultural zone) into the city. Markets, ▪ Ongoing inputs by the French Debt Relief programe (C2D) which provides for the development of decentralized market centers and structures for the Sub – Divisional Council areas located at the city peripheries to absorb the supplies from the rural centers. These include, the bulk market at Nsongwa which is linking the city to other rural settlements along the Bamenda – Enugu road. ▪ Also included is the rehabilitation of some existing market structures located at the city peripheries Capacity Development; Inter-municipal collaborative -

Carbon Pools and Multiple Benefits of Mangroves Assessment for REDD+ in Central Africa

www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, 00100 Kenya Tel: (254 20) 7621234 CARBON POOLS AND Fax: (254 20) 7623927 E-mail: [email protected] web: www.unep.org MULTIPLE BENEFITS of Mangroves Assessment for REDD+ in Central Africa ROGRAMME P UN-REDD NVIRONMENT PROGRAMME UN-REDD PROGRAMME Project Team E UNEP UNEP Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Project Team Empowered lives. Resilient nations. ATIONS N UN-REDD PROGRAMME NITED U UNEP Empowered lives. Resilient nations. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, WCMC, CWCS, University of Douala and KMFRI concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect whatsoever on the part of the UNEP, WCMC, CWCS, University of Douala or KMFRI This publication has been made possible in part by funding from the Government of Norway Published by UNEP Copyright © 2014 United Nations Environment Programme Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation Ajonina, G. J. G. Kairo, G. Grimsditch, T. Sembres, G. Chuyong, D. E. Mibog, A. Nyambane and C. FitzGerald 2014. Carbon Pools and Multiple Benefits of Mangroves Assessment for REDD+ in Central Africa. -

Paradoxes of Natural Resources Management Decentralisation in Cameroon

J. of Modern African Studies, 42, 1 (2004), pp. 91–111. f 2004 Cambridge University Press DOI: 10.1017/S0022278X03004488 Printed in the United Kingdom One step forward, two steps back ? Paradoxes of natural resources management decentralisation in Cameroon Phil Rene´ Oyono* ABSTRACT Theory informs us that decentralisation, a process through which powers, responsibilities and resources are devolved by the central state to lower territorial entities and regionally/locally elected bodies, increases efficiency, participation, equity, and environmental sustainability. Many types and forms of decentralis- ation have been implemented in Africa since the colonial period, with varying degrees of success. This paper explores the process of forest management decen- tralisation conducted in Cameroon since the mid-1990s, highlighting its founda- tions and characterising its initial assets. Through the transfer of powers to peripheral actors for the management of forestry fees, Council Forests and Community [or Village] Forests, this policy innovation could be empowering and productive. However, careful observation and analysis of relationships between the central state and regional/local-level decentralised bodies, on the one hand, and of the circulation of powers, on the other, show – after a decade of imple- mentation – that the experiment is increasingly governed by strong tendencies towards ‘re-centralisation’, dictated by the practices of bureaucrats and state representatives. The paper also confirms recent empirical studies of ‘the capture of decentralised actors’. It finally shows how bureaucrats and state authorities are haunted by the Frankenstein’s monster syndrome, concerning state–local relation- ships in decentralised forest management. INTRODUCTION Decentralisation is not a new phenomenon in Africa: according to Ribot (2002), there have been at least four waves of decentralisation in * Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Yaounde´/Messa, Cameroon. -

Data Collection Survey on the Transport Network Development in Douala, Republic of Cameroon

Republic of Cameroon Direction des Études Techniques, Ministry of Public Works Communauté Urbaine de Douala Ministry of Housing and Urban Development Ministry of Economy, Planning and Regional Development Data Collection Survey on the Transport Network Development in Douala, Republic of Cameroon Final Report February, 2017 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) INGÉROSEC Corporation Metropolitan Expressway Company Limited Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. 6R CR(3) 17-009 Data Collection Survey on the Transport Network Development in Douala, Republic of Cameroon Final Report Contents Area Map ..................................................................................................... i List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ii List of Tables and Figures .............................................................................. vi Summary ...................................................................................................... xv 1.Project Overview 1.1 Background and purpose of the Survey ······································ 1 1.1.1 Background of the Survey ················································· 1 1.1.2 Purpose of the Survey ····················································· 1 1.2 Survey approach ······························································· 2 1.3 Survey Team ··································································· 3 1.4 Field Survey Schedule ························································ 4 1.5