Cameroon City Competitiveness Diagnostic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infrastructure Causes of Road Accidents on the Yaounde – Douala Highway, Cameroon

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of Development Research ISSN: 2230-9926 Vol. 10, Issue, 06, pp. 36260-36266, June, 2020 https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.18747.06.2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS INFRASTRUCTURE CAUSES OF ROAD ACCIDENTS ON THE YAOUNDE – DOUALA HIGHWAY, CAMEROON 1WOUNBA Jean François, 2NKENG George ELAMBO and *3MADOM DE TAMO Morrelle 1Department of Town Planning, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon; 2Director of the National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon: 3Department of Civil Engineering, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT ArticleArticle History: History: The overall goal of this study was to determine the causes of road crashes related to road th ReceivedReceived 24xxxxxx, March, 2019 2020 infrastructure parameters on the National Road No. 3 (N3) and provide measures to improve the ReceivedReceived inin revisedrevised formform safety of all road users. To achieve this, 225 accident reports for the years 2017 and 2018 were th 19xxxxxxxx, April, 2020 2019 th collected from the State Defense Secretariat. This accident data was analyzed using the crash AcceptedAccepted 20xxxxxxxxx May, 2020, 20 19 frequency and the injury severity density criteria to obtain the accident-prone locations (7 critical Published online 25th June, 2020 Published online xxxxx, 2019 sections and 2 critical intersections) and a map presenting these locations produced with ArcGis Key Words: 10.4.1. A site visit of these locations was then performed to obtain the road infrastructure and environment data necessary to get which parameters are responsible for road crashes. -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon

sustainability Article Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon Akhere Solange Gwan 1 and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi 2,3,* 1 Department of Geography and Planning, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Technische Universität Dresden, 01737 Tharandt, Germany 3 Department of Geography, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 14 July 2020; Published: 18 July 2020 Abstract: There is growing interest in the need to understand the link between urban expansion and farmers’ livelihoods in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including Cameroon. This paper undertakes a qualitative investigation of the effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods in Bamenda, a primate city in Cameroon. Taking into consideration two key areas—the Mankon–Bafut axis and the Nkwen Bambui axis—this study analyzes the trends and effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods with a view to identifying ways of making the process more beneficial to the farmers. Maps were used to determine the trend of urban expansion between 2000 and 2015. Twelve farmers drawn from the target sites were interviewed, while three focus group discussions were conducted. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze perceptions of the effects and coping strategies of farmers to urban expansion. Using the livelihoods approach, farmers’ livelihoods repertoires and portfolios were analyzed for the periods before and after urban expansion. Between 2000 and 2015, the surface area for farmlands in Bamenda II and Bamenda III reduced from 3540 ha to 2100 ha and 2943 ha to 1389 ha, respectively. -

Corruption in Cameroon

Corruption in Cameroon CORRUPTION IN CAMEROON - 1 - Corruption in Cameroon © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Cameronn Tél: 22 21 29 96 / 22 21 52 92 - Fax: 22 21 52 74 E-mail : [email protected] Printed by : SAAGRAPH ISBN 2-911208-20-X - 2 - Corruption in Cameroon CO-ORDINATED BY Pierre TITI NWEL Corruption in Cameroon Study Realised by : GERDDES-Cameroon Published by : FRIEDRICH-EBERT -STIFTUNG Translated from French by : M. Diom Richard Senior Translator - MINDIC June 1999 - 3 - Corruption in Cameroon - 4 - Corruption in Cameroon PREFACE The need to talk about corruption in Cameroon was and remains very crucial. But let it be said that the existence of corruption within a society is not specific to Cameroon alone. In principle, corruption is a scourge which has existed since human beings started organising themselves into communities, indicating that corruption exists in countries in the World over. What generally differs from country to country is its dimensions, its intensity and most important, the way the Government and the Society at large deal with the problem so as to reduce or eliminate it. At the time GERDDES-CAMEROON contacted the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung for a support to carry out a study on corruption at the beginning of 1998, nobody could imagine that some months later, a German-based-Non Governmental Organisation (NGO), Transparency International, would render public a Report on 85 corrupt countries, and Cameroon would top the list, followed by Paraguay and Honduras. - 5 - Corruption in Cameroon Already at that time in Cameroon, there was a general outcry as to the intensity of the manifestation of corruption at virtually all levels of the society. -

Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon

Centre for Research on Settlements and Urbanism Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning J o u r n a l h o m e p a g e: http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon Lawrence Akei MBANGA 1 1 The University of Bamenda, Faculty of Arts, Department of Geography and Planning, Bamenda, CAMEROON E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 https://doi.org/10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 K e y w o r d s: human settlements, dynamics, sustainability, Bamenda III, Cameroon A B S T R A C T Every human settlement, from its occupation by a pioneer population continues to undergo a process of dynamism which is the result of socio economic and dynamic factors operating at the local, national and global levels. The urban metabolism model shows clearly that human settlements are the quality outputs of the transformation of inputs by an urban area through a metabolic process. This study seeks to bring to focus the drivers of human settlement dynamics in Bamenda 3, the manifestation of the dynamics and the functional evolution. The study made used of secondary data and information from published and unpublished sources. Landsat images of 1989, 1999 and 2015 were used to analyze dynamics in human settlement. Field survey was carried out. The results show multiple drivers of human settlement dynamism associated with population growth. Human settlement dynamics from 1989, 1999 and 2015 show an evolution in surface area with that of other uses like agriculture reducing. -

Report on the IDB2014 Celebrations in Cameroon

CAMEROON CELEBRATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL DAY FOR BIODIVERSITY Yaounde, Cameroon 14 May 2014 THEME: ISLAND BIODIVERSITY REPORT A cross-section of the exhibition ground including school children and the media Yaounde, 15 May 2014 1 CITATION This document will be cited as MINEPDED 2014. Report on the Celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity in Cameroon ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The organisation of the 2014 Day for Biodiversity was carried out under the supervision of the Minister of Environment, Protection of Nature and Sustainable Development Mr HELE Pierre and the Minister Delegate Mr. NANA Aboubacar DJALLOH. The contributions of the Organising Committee were highly invaluable for the success of the celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity. Members were: AKWA Patrick- Secretary General of MINEPDED- Representative of the Minister at the celebration; GALEGA Prudence- National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity- coordinator of the celebration; WADOU Angele- Sub-Director of Biodiversity and Biosafety, MINEPDED; WAYANG Raphael- Chief of Service for Biodiversity, MINEPDED NFOR Lilian- Environmental Lawyer at the Service of the Technical Adviser No1 of MINEPDED; SHEI Wilson- Project Assistant, ABS; NDIFOR Roland -Representative of IUCN- Cameroon; BANSEKA Hycinth- Representative of Global Water Partnership- Cameroon MBE TAWE Alex- Representative of World Fish Centre- Cameroon 2 TABLE of CONTENT Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………....4 Preparatory activities………………………………………………………………………..5 Media activities………………………………………………………………………………….5 Commemoration of activities…………………………………………………………….6 Exhibition………………………………………………………………………………………....7 Presentation of stands……………………………………………………………………….7 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………12 Photo gallery…………………………………………………………………………………….13 3 INTRODUCTION Cameroon as a member of the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity joined the international community to celebrate the International Day for Biodiversity 2014 under the theme ‘Island Biodiversity”. -

Country Review Report of Cameroon

Country Review Report of Cameroon Review by the Republic of Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia of the implementation by Cameroon of articles 15 – 42 of Chapter III. “Criminalization and law enforcement” and articles 44 – 50 of Chapter IV. “International cooperation” of the United Nations Convention against Corruption for the review cycle 2010 - 2015 Page 1 of 142 I. Introduction 1. The Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption was established pursuant to article 63 of the Convention to, inter alia, promote and review the implementation of the Convention. 2. In accordance with article 63, paragraph 7, of the Convention, the Conference established at its third session, held in Doha from 9 to 13 November 2009, the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention. The Mechanism was established also pursuant to article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention, which states that States parties shall carry out their obligations under the Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States. 3. The Review Mechanism is an intergovernmental process whose overall goal is to assist States parties in implementing the Convention. 4. The review process is based on the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism. II. Process 5. The following review of the implementation by Cameroon of the Convention is based on the completed response to the comprehensive self-assessment checklist received from Cameroon, supplementary information provided in accordance with paragraph 27 of the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism and the outcome of the constructive dialogue between the governmental experts from Cameroon, Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, by means of telephone conferences, and e-mail exchanges and involving: Angola Dr. -

Cameroon CAMEROON SUMMARY Cameroon Is a Bicameral Parliamentary Republic with Two Levels of Government, National and Local (Regions and Councils)

COUNTRY PROFILE 2019 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT SYSTEM IN cameroon CAMEROON SUMMARY Cameroon is a bicameral parliamentary republic with two levels of government, national and local (regions and councils). There is constitutional provision for local government, as well as for an intermediary higher territorial tier (regions), although this has yet to be implemented. The main laws governing local government are Law No. 2004/17 on the Orientation of Decentralization, Law No. 2004/18 on Rules Applicable to Councils, and Law No. 2004/19 on Rules Applicable to Regions. The Ministry of Decentralization and Local Government is responsible for government policy on territorial administration and local government. There are 374 local government councils, consisting of 360 municipal councils and 14 city councils. There are also 45 district sub-divisions within the cities. Local councils are empowered to levy taxes and charges including direct council taxes, cattle tax and licences. The most important mechanism for revenue-sharing is the Additional Council Taxes levy on national taxation, of which 70% goes to the councils. All councils have similar responsibilities and powers for service delivery with the exception of the sub-divisional councils, which have a modified set of powers. Council responsibility for service delivery includes utilities, town planning, health, social services and primary education. 1. NATIONAL GOVERNMENT Q Decree 1987/1366: City Council of Douala Cameroon is a unitary republic with a Q Law 2009/019 on the Local Fiscal System 10.1a bicameral parliament. The head of Q Law 2012/001 on the Electoral Code, state is the president, who is directly as amended by Law 2012/017. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

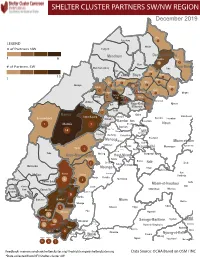

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: a Geopolitical Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal December 2019 edition Vol.15, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: A Geopolitical Analysis Ekah Robert Ekah, Department of 'Cultural Diversity, Peace and International Cooperation' at the International Relations Institute of Cameroon (IRIC) Doi:10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 Abstract Anglophone Cameroon is the present-day North West and South West (English Speaking) regions of Cameroon herein referred to as No-So. These regions of Cameroon have been restive since 2016 in what is popularly referred to as the Anglophone crisis. The crisis has been transformed to a separatist movement, with some Anglophones clamoring for an independent No-So, re-baptized as “Ambazonia”. The purpose of the study is to illuminate the geopolitical perspective of the conflict which has been evaded by many scholars. Most scholarly write-ups have rather focused on the causes, course, consequences and international interventions in the crisis, with little attention to the geopolitical undertones. In terms of methodology, the paper makes use of qualitative data analysis. Unlike previous research works that link the unfolding of the crisis to Anglophone marginalization, historical and cultural difference, the findings from this paper reveals that the strategic location of No-So, the presence of resources, demographic considerations and other geopolitical parameters are proving to be responsible for the heightening of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon and in favour of the quest for an independent Ambazonia.