When Moderate Voters Prefer Extreme Parties: Policy Balancingin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Movement and the Right to Protest

statewatch monitoring the state and civil liberties in the UK and Europe vol 13 no 1 January-February 2003 Free movement and the right to protest Information, intelligence and "personal data" is to be gathered on: potential demonstrators and other groupings expected to travel to the event and deemed to pose a potential threat to the maintenance of public law and order The freedom of movement for all EU citizens, one of its four by the unaccountable EU Police Chiefs Task Force, and the basic freedoms of the EU, is under attack when it comes to Security Office of the General Secretariat of the Council of the people exercising their right to protest. European Union (the 15 EU governments) is to "advise" on The "freedom of movement" of people is held to mean the operational plans to combat protests (see Viewpoint, page 21). right of citizens to move freely between the 15 countries of the Information, intelligence and "personal data" on: EU without being checked or controlled or having to say why potential demonstrators and other groupings expected to travel to the they are travelling. Martin Bangemann, then the EC event and deemed to pose a potential threat to the maintenance of Commissioner for the Internal Market, told the European public law and order Parliament in 1992: "We want any EC citizen to go from are to be supplied by each national police and security agency to Hamburg to London without a passport" (Statewatch, vol 2 no 6). the state where the protest is planned - on a monthly, then weekly This "freedom" was never uniformly implemented but today it and finally daily basis up to the event. -

Changing Party Electorates and Economic Realignment

Changing party electorates and economic realignment Explaining party positions on labor market policy in Western Europe Dominik Geering and Silja Häusermann, University of Zurich [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Socio-structural change has led to important shifts of voters, such as middle class voters increasingly voting for the left and working class voters increasingly voting for the populist right. These electoral shifts blur the voter-party alignments, which prevailed during the post- war period. Consequently, comparative politics scholars have started to question whether parties still represent the class interests of their voters. Most contributions answer this question negatively, arguing that parties have detached themselves from the class profile of their electorates. We argue that this conclusion is erroneous as it relies on assumptions on and measures of class structuration that are outdated. We show that the class profile of party electorates still predicts parties’ positions on labor market policies. However, these voter- party alignments become observable empirically only if we a) use a post-industrial schema of class stratification to characterize party constituencies and b) distinguish between different dimensions of labor market policy, notably redistribution and activation. For our analysis we explore the class profiles of electorates and party positions on labor market policies in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK. We use two sources of data: Micro-level survey data (ISSP 2000 and 2006) and a newly compiled data set on party positions during electoral campaigns in the 2000s. We have three main findings. First, we show that the distinction between working class and middle-class parties does not explain party positions anymore, because the middle class has expanded and become heterogeneous. -

Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls

Alan Wall and Mohamed Salih Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Indonesia – Voting Station 2005 Index 1 Introduction 5 2 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 6 2.1 What Is Electoral Engineering? 6 2.2 Basic Terms and Classifications 6 2.3 What Are the Potential Objectives of an Electoral System? 8 3 2.4 What Is the Best Electoral System? 8 2.5 Specific Issues in Split or Post Conflict Societies 10 2.6 The Post Colonial Blues 10 2.7 What Is an Appropriate Electoral System Development or Reform Process? 11 2.8 Stakeholders in Electoral System Reform 13 2.9 Some Key Issues for Political Parties 16 3 Further Reading 18 4 About the Authors 19 5 About NIMD 20 Annex Electoral Systems in NIMD Partner Countries 21 Colophon 24 4 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Introduction 5 The choice of electoral system is one of the most important decisions that any political party can be involved in. Supporting or choosing an inappropriate system may not only affect the level of representation a party achieves, but may threaten the very existence of the party. But which factors need to be considered in determining an appropriate electoral system? This publication provides an introduction to the different electoral systems which exist around the world, some brief case studies of recent electoral system reforms, and some practical tips to those political parties involved in development or reform of electoral systems. Each electoral system is based on specific values, and while each has some generic advantages and disadvantages, these may not occur consistently in different social and political environments. -

International Social Survey Program: Work Orientations II, 1997

ICPSR Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research International Social Survey Program: Work Orientations II, 1997 International Social Survey Program (ISSP) ICPSR 3032 INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SURVEY PROGRAM: WORK ORIENTATIONS II, 1997 (ICPSR 3032) Principal Investigator International Social Survey Program (ISSP) First ICPSR Version November 2000 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 BIBLIOGRAPHIC CITATION Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: International Social Survey Program (ISSP). INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SURVEY PROGRAM: WORK ORIENTATIONS II, 1997 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. Koeln, Germany: Zentralarchiv fuer Empirische Sozialforschung [producer], 1999. Koeln, Germany: Zentralarchiv fuer Empirische Sozialforschung/Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributors], 2000. REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ON USE OF ICPSR RESOURCES To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Please indicate in a cover letter which data were used. DATA DISCLAIMER The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. DATA COLLECTION DESCRIPTION International Social Survey Program (ISSP) INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SURVEY PROGRAM: WORK ORIENTATIONS II, 1997 (ICPSR 3032) SUMMARY: The International Social Survey Program (ISSP) is an ongoing program of crossnational collaboration. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

NATIONAL IDENTITY AND COSMOPOLITAN COMMUNITY AMONG DUTCH GREEN PARTY MEMBERS Written by Matthias Schmal and supervised by Luc Lauwers: A thesis part of the Master’s program Cultural Anthropology: Sustainable Citizenship at Utrecht University. August 2017 2 Green Communities National Identity and Cosmopolitan Community Among Dutch Green Party Members A thesis as part of the Master’s program Cultural Anthropology: Sustainable Citizenship at Utrecht University. Written by Matthias Schmal, supervised by Luc Lauwers. Cover by Matthias Schmal. August 4, 2017 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 6 METHODS .............................................................................................................................................. 11 Participant Observation .................................................................................................................... 11 Interviewing ...................................................................................................................................... 13 Online and Media Ethnography ........................................................................................................ 14 A LOST SENSE OF COMMUNITY ........................................................................................................... -

The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis

Sara B. Hobolt, James Tilley Fleeing the centre: the rise of challenger parties in the aftermath of the Euro crisis Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Hobolt, Sara and Tilley, James (2016) Fleeing the centre: the rise of challenger parties in the aftermath of the Euro crisis. West European Politics, 39 (5). pp. 971-991. ISSN 1743-9655 DOI: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871 © 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66032/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis SARA B. HOBOLT Sutherland Chair in European Institutions European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] JAMES TILLEY Professor of Politics Department of Politics and International Relations University of Oxford Email: [email protected] **ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST EUROPEAN POLITICS (FORTHCOMING IN 2016)** The Eurozone crisis has altered the party political landscape across Europe. -

The Politics of the 'Third Way'

PARTY POLITICS VOL 8. No.5 pp. 507–524 Copyright © 2002 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi THE POLITICS OF THE ‘THIRD WAY’ The Transformation of Social Democracy in Denmark and The Netherlands Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Kees van Kersbergen ABSTRACT The development of European Social Democracy has once more attracted significant scholarly attention. This time, the debate is centred around the ‘third way’ as the catchphrase for the transformation of European Social Democracy. Based on the experience of the Danish and Dutch Social Democrats, two questions are raised in this article, namely what has caused the renewal of Social Democracy and what explains different sequences of change in different countries? The answer to the first question is that the transformation is driven by the search for a new formula for combining social justice and effective economic governance after the failure of the Keynesian formula in the 1970s and 1980s. This, and not so much changes in the preferences of the electorate in a liberal and libertarian direction, is driving the transformation. The answer to the second question is that differences in the strategic situation of the Social Democratic parties in terms of office-seeking and holding on to power explain different sequences. KEY WORDS Ⅲ Denmark party change Social Democracy The Netherlands Ⅲ ‘third way’ Introduction In 2000, Social Democratic parties were in office in most West European countries, which sparked off a new wave of academic study on Social Democracy (e.g. Glyn, 2001; see Powell (2001) for an overview). The debate has centred around the concept of the ‘third way’ as theoretically elabor- ated by Giddens (1998, 2000, 2001) and politically advanced, for instance, in the Blair–Schröder paper (1999). -

Mednarodna Splošna Družboslovna Anketa (ISSP): Stališča O Delu II

Mednarodna splošna družboslovna anketa (ISSP): Stališča o delu II International Social Survey Programme ADP - IDNo: ISSP97 Izdajatelj: Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov, 2002 URL: https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/issp97 E-pošta za kontakt: [email protected] Opis raziskave Osnovne informacije o raziskavi ADP - IDNo: ISSP97 Glavni avtor(ji): International Social Survey Programme, Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za družbene vede Ostali (strokovni) sodelavci: Kelly, Jonathan, Research School of Social Science, Avstralija;nacionalni koordinator Guidorossi, Giovanna, Ricerca Sociale e di Marketing, Italija;nacionalni koordinator Haller, Max, Institute of Sociology, University of Graz, Avstrija;nacionalni koordinator Smith, Tom W., National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, ZDA;nacionalni koordinator Becker, Jos, Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, Nizozemska;nacionalni koordinator Park, Alison, Social and Community Planning Research, Velika Britanija;nacionalni koordinator Ward, Connor, Social Science Research Centre, Irska;nacionalni koordinator Kolosi, Tamas, Tarsadalokumtatasi Informatikai Egyesules, Madžarska;nacionalni koordinator Harkness, Janet, Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden, und Analysen, Nemčija;nacionalni koordinator Cichomski, Bogdan, Instytut Filozofii i Socjologii, Poljska;nacionalni koordinator Kalgraff Skjak, Knut, Norwegian Social Science Data Service, Norveška;nacionalni koordinator Lewin-Epstein, Noah, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Tel Aviv University, Izrael;nacionalni koordinator Gendal, -

Codebook Information

Zentralarchiv für GESIS Empirische Sozialforschung Preface ZA Study 3440 ISSP 2000 ENVIRONMENT Participating Nations: Austria Bulgaria Canada Chile Czech Republic Denmark Finland Germany Ireland Israel Japan Latvia Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Philippines Portugal Russia Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States Zentralarchiv fuer Empirische Sozialforschung an der Universitaet zu Koeln Bachemer Str. 40 D-50931 Koeln Tel: (+) 49 221-4 7694 - 0 Fax: (+) 49 221-4 7694 - 44 e-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.gesis.org/ZA/ First edition: March 2003 ZA-No. 3440 I S S P 2000 - Environment II Page I - 2 Table of Contents Preface Acknowledgement of Assistance ............................................................................................... 3 An Introduction to the ISSP ....................................................................................................... 5 The International Social Survey Programme ............................................................... 5 ISSP Modules 1985 - 2000........................................................................................... 6 The ISSP Members Institute Addresses & ISSP Contacts........................................... 7 Members of the Drafting Committee ......................................................................... 15 Study Descriptions.................................................................................................................... 16 Study Description: Austria ..................................................................................... -

Registration List 17.05.2016.Xlsx

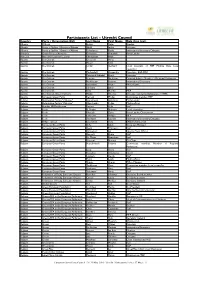

Participants List - Utrecht Council Country Party / Organisation (EU) Last Name First Name Role (free text) Albania 350.org Hüzeir Vatan Speaker Albania Partia e Gjelber / Greens of Albania Abdili Indrit Delegate Albania Partia e Gjelber / Greens of Albania Ushtelenca Keida International Secretary, Delegate Armenia Green Party of Armenia Dovlatyan Armenak Party Leader Armenia National Renaissance party Khanumyan Hayk Austria Die Grünen Groeschl Anna Austria Die Grünen Hauer Felix Austria Die Grünen Jordan Gerhard Local Assistant of MEP Monika Vana, Local councillor Austria Die Grünen Medwedeff Alexandra Delegate - EGP AMC Austria Die Grünen Meinhard-Schiebel Birgit Delegate Austria Die Grünen Petrovic Madeleine Financial Advisor, Member of Regional Parliament Austria Die Grünen Puchberger Susanne International Secretary Austria Die Grünen Rossmann Bruno MP, Delegate Austria Die Grünen Schwarz Jakob Austria Die Grünen Vana Monika MEP Austria Die Grünen, Green Farmers Waitz Thomas Delegate, Landwirtschaftskammer STMK Austria European Green Party Reimon Michel Committee member, MEP Belarus Bielaruskaja Partyja "Zialonye" Dorofeyeva Anastasia Party Leader Belarus Bielaruskaja Partyja "Zialonye" Kharchenko Polina Media officer Belgium Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Caruso Aldo Staff Belgium Ecolo El Ghabri Mohssin Local councillor Belgium Ecolo Khattabi Zakia Party Leader, Chairperson Belgium Ecolo Lamberts Philippe MEP Belgium Ecolo Standaert Laurent International Secretary, Delegate Belgium ENGS - Groen Cooreman To n y ENGS Chairperson Belgium European -

ISSP): Ekologija II

Mednarodna splošna družboslovna anketa (ISSP): Ekologija II International Social Survey Programme ADP - IDNo: ISSP00 Izdajatelj: Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov, 2002 URL: https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/issp00 E-pošta za kontakt: [email protected] Opis raziskave Osnovne informacije o raziskavi ADP - IDNo: ISSP00 Glavni avtor(ji): International Social Survey Programme, Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za družbene vede Ostali (strokovni) sodelavci: Kelly, Jonathan, Research School of Social Science, Avstralija;nacionalni koordinator Guidorossi, Giovanna, Ricerca Sociale e di Marketing, Italija;nacionalni koordinator Haller, Max, Institute of Sociology, University of Graz, Avstrija;nacionalni koordinator Smith, Tom W., National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, ZDA;nacionalni koordinator Becker, Jos, Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, Nizozemska;nacionalni koordinator Park, Alison, Social and Community Planning Research, Velika Britanija;nacionalni koordinator Ward, Connor, Social Science Research Centre, Irska;nacionalni koordinator Robert, Peter, Tarsadalokumtatasi Informatikai Egyesules, Madžarska;nacionalni koordinator Harkness, Janet, Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden, und Analysen, Nemčija;nacionalni koordinator Cichomski, Bogdan, Instytut Filozofii i Socjologii, Poljska;nacionalni koordinator Kalgraff Skjak, Knut, Norwegian Social Science Data Service, Norveška;nacionalni koordinator Lewin-Epstein, Noah, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Tel Aviv University, Izrael;nacionalni koordinator Gendal, Philip -

Estimating Party Policy Positions: Comparing Expert Surveys and Hand-Coded Content Analysis

Electoral Studies 26 (2007) 90e107 www.elsevier.com/locate/electstud Estimating party policy positions: Comparing expert surveys and hand-coded content analysis Kenneth Benoit a,Ã, Michael Laver b a Department of Political Science, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland b New York University, New York, USA Abstract In this paper we compare estimates of the left-right positions of political parties derived from an expert survey recently completed by the authors with those derived by the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP) from the content analysis of party manifestos. Having briefly described the expert survey, we first explore the substantive policy content of left and right in the expert survey estimates. We then compare the expert survey to the CMP method on methodological grounds. Third, we directly compare the expert survey results to the CMP results for the most recent time period available, revealing some agreement but also numerous inconsistencies in both cross-national and within-country party placements. We conclude by investigating the CMP scores in more detail, focusing on the series of British left-right placements and the components of these scores. Ó 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Left-right; Political parties; Expert survey; Comparative manifestos project; Content analysis 1. Introduction: measuring left-right on a left-right dimension has become an important empirical task. This task can be accomplished in Both theoretical models and substantive descrip- a range of different ways. These include mass surveys tions of party competition very often use the notion of party voters, elite surveys of party politicians, di- of a left-right dimension as a fundamental part of mensional analysis of the roll call votes of party leg- their conceptual toolkit.