Swinburne Research Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daredevil by Frank Miller Box Set Ebook Free Download

DAREDEVIL BY FRANK MILLER BOX SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank Miller | 1896 pages | 15 Oct 2019 | Marvel Comics | 9781302919108 | English | New York, United States Daredevil By Frank Miller Box Set PDF Book Readers also enjoyed. Elektra 1 Items 1. This is the email address that you previously registered with on angusrobertson. Auction 1. Return to Book Page. Would you like us to keep your Bookworld order history? Again this run is famous for a reason and its definitely an enjoying collection. Dude really wa Despite being the companion piece to Frank Miller's Daredevil Omnibus, they actually put all the best stories in this one. I've never read a Miller book quite this abstract, Sienkiewicz art definitely helps but overall it didn't grab me too much. Seller does not offer returns. This story is brilliant, it shows kingpin at his worst, destroying daredevils life bit by bit. Hardcover , pages. El problema de los libros recopilatorios es que la variedad de artistas puede generar una muy amplia escala de calidad a lo largo de la obra. Delivery Options. Home Gardening International Subscriptions. Sign In Register. However, it's the writing that really sets it apart. Daredevil 7th Series Annual. Get A Copy. Daredevil 5th Series. Accept Close Privacy Policy. Canada Only. But we also get a long fight with Nuke and a comic that quickly becomes more about Captain America than Daredevil. The art is very strange. No No, I don't need my Bookworld details anymore. Average rating 4. Mirallegro rated it really liked it. This omni starts off with a 2 part story with spiderman in which spiderman becomes blind, so daredevil helps out. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

Bryan HITCH's Ultimate

v BRYan HITCH’S ULTIMATE FOREWORD BY JOSS WHEDON Press escape to return to normal view Bryan Hitch trademarks New York establishing shot It is inevitable that your own style and personality comes through in your work, Establishing shots make the location of the and that readers become familiar with that. I like my action to be ‘big’, and the action a key part of the story, be it a city, a building or a spaceship. The detailed devices I use for this have become known as my ‘trademarks’. To me, it’s all just panorama here provides a level of reality, and is also a useful tool to give the reader a part of conveying a story with as much impact as possible. moment of space to breathe and re-adjust. 24 Press escape to return to normal view 1. Establishing shots These widescreen shots really put the reader The superhero close-up Not all comics are keen to show the reality in the thick of the action. of the environment in which the story is 3. Close-up portraits This is a close-up of Doctor Impossible from the novel Soon I will be Invincible, rendered in a set, but to me it is an important part of the This is all about choosing a viewpoint to give classic foreshortened pose for the front cover. I storytelling process. It makes the reader feel you an angle of a face that you’ve never seen think this works really well as a good example of involved and helps to achieve verisimilitude. -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

GRAPHIC NOVELS IN ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Madeleine Grumet James Trier Jeff Greene Lucila Vargas Renee Hobbs © 2012 Cary Gillenwater ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CARY GILLENWATER: Graphic novels in advanced English/language arts classrooms: A phenomenological case study (Under the direction of Madeleine Grumet) This dissertation is a phenomenological case study of two 12th grade English/language arts (ELA) classrooms where teachers used graphic novels with their advanced students. The primary purpose of this case study was to gain insight into the phenomenon of using graphic novels with these students—a research area that is currently limited. Literature from a variety of disciplines was compared and contrasted with observations, interviews, questionnaires, and structured think-aloud activities for this purpose. The following questions guided the study: (1) What are the prevailing attitudes/opinions held by the ELA teachers who use graphic novels and their students about this medium? (2) What interests do the students have that connect to the phenomenon of comic book/graphic novel reading? (3) How do the teachers and the students make meaning from graphic novels? The findings generally affirmed previous scholarship that the medium of comic books/graphic novels can play a beneficial role in ELA classrooms, encouraging student involvement and ownership of texts and their visual literacy development. The findings also confirmed, however, that teachers must first conceive of literacy as more than just reading and writing phonetic texts if the use of the medium is to be more than just secondary to traditional literacy. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

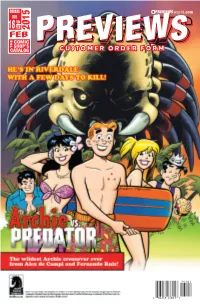

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

“I Am the Villain of This Story!”: the Development of the Sympathetic Supervillain

“I Am The Villain of This Story!”: The Development of The Sympathetic Supervillain by Leah Rae Smith, B.A. A Thesis In English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Wyatt Phillips Chair of the Committee Dr. Fareed Ben-Youssef Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leah Rae Smith Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to share my gratitude to Dr. Wyatt Phillips and Dr. Fareed Ben- Youssef for their tutelage and insight on this project. Without their dedication and patience, this paper would not have come to fruition. ii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...iv I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 II. “IT’S PERSONAL” (THE GOLDEN AGE)………………………………….19 III. “FUELED BY HATE” (THE SILVER AGE)………………………………31 IV. "I KNOW WHAT'S BEST" (THE BRONZE AND DARK AGES) . 42 V. "FORGIVENESS IS DIVINE" (THE MODERN AGE) …………………………………………………………………………..62 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………76 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………82 iii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ABSTRACT The superhero genre of comics began in the late 1930s, with the superhero growing to become a pop cultural icon and a multibillion-dollar industry encompassing comics, films, television, and merchandise among other media formats. Superman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, and their colleagues have become household names with a fanbase spanning multiple generations. However, while the genre is called “superhero”, these are not the only costume clad characters from this genre that have become a phenomenon.