Arxiv:2002.08292V1 [Hep-Ph] 19 Feb 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Quigg · Physicist

CHRIS QUIGG · PHYSICIST Theoretical Physics Department 1218 Howard Circle Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Wheaton, Illinois 60187 P.O. Box 500, Batavia, Illinois 60510 +1 630.840.3578 +1 630.660.1370 [email protected] [email protected] lutece.fnal.gov chrisquigg.com Born 15 December 1944 in Bainbridge, Maryland, USA · United States citizen PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Theoretical Physics Department, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, 1974–present; Distinguished Scientist Emeritus, 2017–present; Department Head, 1977–1987. Superconducting Super Collider Central Design Group Deputy Director for Operations, 1987–1989. Institute for Theoretical Physics, State University of New York, Stony Brook Associate Professor, 1974; Assistant Professor, 1971–4; Research Associate, 1970–1. SECONDARY AFFILIATION University of Chicago Department of Physics and Enrico Fermi Institute, Professor (part-time), 1982–1991; Professorial Lecturer, 1978–1982; Visiting Scholar, Enrico Fermi Institute, 1974–1978. EDUCATION Yale University · B.S., Physics, 1966. Magna cum laude, with honors with exceptional distinction in physics. University of California, Berkeley · Ph.D., Physics, 1970; Thesis advisor, J. D. Jackson. Two-Reggeon-Exchange Contributions to Scattering Amplitudes at High Energies. HONORS AND AWARDS Phi Beta Kappa, 1966. Sigma Xi, 1966. De Forest Pioneers Prize (Yale University), 1966. Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, 1966–1967. HONORS AND AWARDS continued University of California Science Fellowship, 1967–1970. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Research Fellowship, 1974–1978. Fellow of the American Physical Society, 1983, for his numerous significant contributions in the theory of elementary particle physics and high energy collisions. His activities span work on multiparticle production, production and decay of intermediate bosons, and signatures of charmed mesons. One of the many notable contributions is the work on Quarkonium states, noted for lucid and seminal nonrelativistic quantum me- chanics application. -

2007 Annual Report APS

American Physical Society APS 2007 Annual Report APS The AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY strives to: Be the leading voice for physics and an authoritative source of physics information for the advancement of physics and the benefit of humanity; Collaborate with national scientific societies for the advancement of science, science education, and the science community; Cooperate with international physics societies to promote physics, to support physicists worldwide, and to foster international collaboration; Have an active, engaged, and diverse membership, and support the activities of its units and members. Cover photos: Top: Complementary effect in flowing grains that spontaneously separate similar and well-mixed grains into two charged streams of demixed grains (Troy Shinbrot, Keirnan LaMarche and Ben Glass). Middle: Face-on view of a simulation of Weibel turbulence from intense laser-plasma interactions. (T. Haugbolle and C. Hededal, Niels Bohr Institute). Bottom: A scanning microscope image of platinum-lace nanoballs; liposomes aggregate, providing a foamlike template for a platinum sheet to grow (DOE and Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM). Text paper is 50% sugar cane bagasse pulp, 50% recycled fiber, including 30% post consumer fiber, elemental chlorine free. Cover paper is 50% recycled, including 15% post consumer fiber, elemental chlorine free. Annual Report Design: Leanne Poteet/APS/2008 Charts: Krystal Ferguson/APS/2008 ast year, 2007, started out as a very good year for both the American Physical Society and American physics. APS’ journals and meetings showed solidly growing impact, sales, and attendance — with a good mixture Lof US and foreign contributions. In US research, especially rapid growth was seen in biophysics, optics, as- trophysics, fundamental quantum physics and several other areas. -

In Leon's Company, It Seemed That Anything Might Be Possible

In Leon’s company, it seemed that anything might be possible Chris Quigg email:[email protected] Theoretical Physics Department Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory P.O. Box 500, Batavia, Illinois 60510 USA 5 January 2020 FERMILAB-PUB-20-001-T Memorial sessions celebrated Leon Lederman, Helen Edwards, and Burton Richter at the April 2019 Meeting of the American Physical Society in Denver. In the session entitled Honoring Leon Lederman, Sally Dawson gave an overview of Leon’s scientific career, Marge Bardeen reviewed his work in science education, and I spoke of his years as Fermilab Director. Presentation materials for all three sessions are archived at http://j.mp/31mNkHA. This essay is drawn from my lecture; my slides can be found at https://bit.ly/2QJ7Jmw. Leon Lederman in 1983. (Fermilab Creative Services) In 1978, Leon Lederman put aside a promising career in experimental physics that had spanned three decades to accept the appointment as Director of Fermilab—the Enrico Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Leon was tied to Fermilab even before it existed. He had discov- ered early in life that if he took himself seriously, others were likely 1 L. M. Lederman, “The Truly National to take him seriously as well. As the community pondered a new ac- Laboratory (TNL),” in Super-High- Energy Summer Study, Brookhaven celerator in the 100-GeV and above range, Leon delivered a manifesto Report No. BNL-AADD-6 (1963), pp. for what he called a Truly National Laboratory.1 8–11. He gave voice to a complaint of university users that they had not been treated justly at Berkeley and Brookhaven, where the very powerful in-house groups would—according to Leon—consume all the prime beam time for themselves, and only then distribute scraps among the sorry supplicants from Columbia University and other institutions. -

Perspectives and Questions …

Perspectives and Questions Meditations on the Future of Particle Physics Chris Quigg Fermilab Chicago HEP Seminar · May 13, 2019 Supplemental reading: \Dream Machines," arXiv:1808.06036 CHF200 Note (2018) many scales Lifetimes 136 21 Xeββνν : 3:2 × 10 yr 124 22 XeECECνν : 2:6×10 yr p : > 1029−33 yr Chris Quigg Perspectives and Questions . UCHEP · 05.13.2019 1 / 39 The importance of the 1-TeV scale EW theory does not predict Higgs-boson mass Thought experiment: conditional upper bound W +W −; ZZ; HH; HZ satisfy s-wave unitarity, p 1=2 provided MH . (8π 2=3GF) ≈ 1 TeV If bound is respected, perturbation theory is \everywhere" reliable If not, weak interactions among W ±; Z; H become strong on 1-TeV scale New phenomena( H or something else) are to be found around 1 TeV Chris Quigg Perspectives and Questions . UCHEP · 05.13.2019 2 / 39 Where is the next important scale? (Higher energies needed to measure HHH, verify that H regulates WLWL) Planck scale ∼ 1:2 × 1019 GeV (3 + 1-d spacetime); ∼ 1:6 × 10−35 m Unification scale ∼ 1015 −16 GeV ΛQCD ∼ scale of confinement, chiral symmetry breaking At what scale are charged-fermion masses set (Yukawa couplings)? At what scale are neutrino masses set? Will new physics appear at 1×; 10×; 100×;::: EW scale? Might new phenomena appear at macroscopic scales? Chris Quigg Perspectives and Questions . UCHEP · 05.13.2019 3 / 39 The Great Lesson of Twentieth-Century Science The human scale of space and time is not privileged for understanding Nature, and may even be disadvantaged. -

LHC Physics Potential Vs. Energy: Considerations for the 2011 Run Chris Quigg*

FERMILAB{FN{0913{T Rev. February 1, 2011 LHC Physics Potential vs. Energy: Considerations for the 2011 Run Chris Quigg* Theoretical Physics Department Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Batavia, Illinois 60510 USA and CERN, Department of Physics, Theory Unit CH1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland Parton luminosities are convenient for estimating how the physics potential of Large Hadron Collider experiments depends on the energy of the proton beams. I quan- tify the advantage of increasing the beam energy from 3:5 TeV to 4 TeV. I present parton luminosities, ratios of parton luminosities, and contours of fixed parton lumi- nosity for gg, ud¯, qq, and gq interactions over the energy range relevant to the Large Hadron Collider, along with arXiv:1101.3201v2 [hep-ph] 1 Feb 2011 example analyses for specific processes. This note ex- tends the analysis presented in Ref. [1]. Full-size figures are available as pdf files at lutece.fnal.gov/PartonLum11/. *E-mail:[email protected] 2 Chris Quigg 1 Preliminaries The 2009-2010 run of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN is complete, with the delivery of some 45 pb−1 of proton-proton collisions at 3:5 TeV per beam to the ATLAS and CMS experiments. The primary objective of the run, to commission and ensure stable operation of the accelerator complex and the experiments, has been achieved, and much has been learned about machine operation. The experiments succeeded in \rediscovering" the standard model of particle physics, and using familiar physics objects such as W ±, Z0, J= , Υ, jets, b-hadrons, and top-quark pairs to tune detector performance. -

![Learning to See at the Large Hadron Collider Arxiv:1001.2025V1 [Hep-Ph] 12 Jan 2010](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3138/learning-to-see-at-the-large-hadron-collider-arxiv-1001-2025v1-hep-ph-12-jan-2010-2963138.webp)

Learning to See at the Large Hadron Collider Arxiv:1001.2025V1 [Hep-Ph] 12 Jan 2010

FERMILAB-FN-0849-T January 12, 2010 Learning to See at the Large Hadron Collider Chris Quigg* Theoretical Physics Department Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Batavia, Illinois 60510 USA Physics Department, Technical University Munich D-85748 Garching, Germany Arnold Sommerfeld Center for Theoretical Physics Ludwig-Maximilians-Universit¨atM¨unchen D-80333 M¨unchen, Germany Theory Group, Physics Department, CERN CH-1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland The staged commissioning of the Large Hadron Collider presents an opportunity to map gross features of particle production over a significant energy range. I suggest a vi- sual tool|event displays in (pseudo)rapidity{transverse- momentum space|as a scenic route that may help arXiv:1001.2025v1 [hep-ph] 12 Jan 2010 sharpen intuition, identify interesting classes of events for further investigation, and test expectations about the underlying event that accompanies large-transverse- momentum phenomena. *E-mail:[email protected] 2 Chris Quigg The first proton-proton collisions have occurred in CERN's Large Hadron Collider, at energies of 450 GeV and 1:18 TeV per beam, and the experi- mental collaborations have reported their initial looks at the data [1]. Early in 2010, the LHC is projected to run at 3:5 TeV per beam, with the energy increasing later in the run to perhaps 5 TeV per beam, or beyond. The prime objective of the 2009{2010 run is to commission and ensure stable operation of the accelerator complex and the experiments. For the ex- periments, an essential task is to \rediscover" the standard model of particle physics, and to use familiar physics objects such as W ±, Z0, J= , Υ, jets, b-hadrons, and top-quark pairs to tune detector performance. -

Theoretical Physics

2015 ANNUAL REPORT INSTItuto DE FÍSICA CORPUSCULAR 2 3 CONTENTS BIENVENIDA – BENVINGUDA – WELCOME............................................. 4 1. STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION...................................................... 9 About IFIC....................................................................................... 9 Organization, scientific departments and support units............11 Personnel (31 Dec 2015)................................................................ 17 2. RESEARCH ACTIVITIES.........................................................................21 Experimental physics......................................................................21 Theoretical physics......................................................................... 40 3. PUBLICATIONS.....................................................................................55 Experimental physics......................................................................56 Theoretical physics.........................................................................70 Books .............................................................................................. 78 4. TRAINING..............................................................................................79 Teaching activities..........................................................................79 Ph.D. theses.....................................................................................79 5. CONFERENCES, SEMINARS AND COLLOQUIA...................................80 Conferences -

From the Tevatron to Project X

CERN Courier October 2011 Viewpoint From the Tevatron to Project X As the Tevatron era ends, Pier Oddone, experiments using beams of muons and director, kaons; it will also produce copious quantities Pier Oddone looks at past Fermilab. of rare nuclear isotopes for the study of fundamental symmetries. Coupled to success, as well as future the existing Main Injector synchrotron, Project X will deliver megawatt beams to promise, at Fermilab. the Long-Baseline Neutrino Experiment. A strong programme in rare processes is developing now at Fermilab with the The end of September marks the end of an muon-to-electron conversion and muon g-2 era at Fermilab, with the shut down of the experiments. A strong foundation for Project Tevatron after 28 years of operation at the X exists at Fermilab, with expertise in frontiers of particle physics (CERN Courier high-power beams, neutrino beamlines, and March 2011 p5). The Tevatron’s far-reaching The life of the Tevatron is marked by superconducting RF technology. legacy spans particle physics, accelerator historic discoveries that established the Project X’s rare-process physics science and industry. The collider Standard Model. Tevatron experiments programme is complementary to the LHC. If established Fermilab as a world leader in discovered the top quark, five B baryons the LHC produces a host of new phenomena, particle-physics research, a role that will and the Bc meson, and observed the first then Project X experiments will help be strengthened with a new set of facilities, τ neutrino, direct CP violation in kaon elucidate the physics behind them. -

Fermilab Poised to Leapfrog Thews and Zo Have Been Tidied Away

-~-2----------------------------------------------NEVVS-------------------------------N_ATU__ RE__ v_o_L_.~_3_1_6_Ju_N_E_I_~_3 High-energy physics in high-energy physics from the United States. He also says that the net cost of SF50 million could be brought down to Another flavour of quark? SF20-30 million by using some of the con HARD on the heels of the discovery of the duced the Zs, Ws and possibly top. There is tribution from the new member, Spain Z0 particle by the UA1 group at CERN a proposal for a SF50 million (£15 million) (which wished to support mostly lower (European Organization for Nuclear development of the collider to improve its energy physics at CERN). And the money Research), rumours were rife that the luminosity (production rate of events such would be spread over three years, he pleads. group has also discovered the "top" quark as Ws and Zs) tenfold. This would take But members are more likely to require - the sixth flavour in the family. This three years and could thus be just ahead of that if the collider is to be improved, it development has not been confirmed, Fermilab (see below). The snag is that the should be within a constant CERN budget. however. The position seems to be that member governments of CERN are not That might entail a delay in the LEP pro among its harvest of possible W± and zo flush with cash just now. gramme - which is itself in competition events, the UA1 group has a few events that Even so, Dr Erwin Gabathuler, CERN's with an American proposal, the SLAC are "consistent with" the existence of top. -

APS Announces Winners for 2011

FACES AND PLACES A w A r ds A selection of 2011 APS prize-winners: (left to right) Yaroslav Derbenev, Gerald Gabrielse and Ian Hinchliffe. (Courtesy Jefferson Lab, Harvard and ATLAS.) APS announces winners for 2011 The American Physical Society (APS) has cooling, and the related neutrino processes and ionization cooling, round-to-flat beam announced its awards for 2011, including and astrophysical phenomena”. transformations, FELs and electron–ion some major prizes in particle physics and The Lars Onsager Prize is another award for colliders.” related fields. theoretical physics, in this case to recognize In nuclear physics the Tom W Bonner With physics at the LHC having started outstanding research in theoretical statistical Prize is to recognize and encourage during 2010, it is appropriate that the physics, including the quantum fluids. The outstanding experimental research in award that recognizes and encourages 2011 award goes to Alexander A Belavin nuclear physics, including the development outstanding achievement in particle of the L D Landau Institute for Theoretical of a method, technique or device that theory – the J J Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Physics, Alexander B Zamolodchikov of significantly contributes in a general way to Particle Physics for 2011– goes to Ian Rutgers University and Alexander M Polyakov nuclear-physics research. Richard F Casten Hinchliffe of the Lawrence Berkeley of Princeton University for their “outstanding of Yale University receives the 2011 prize for National Laboratory (LBNL) and Kenneth contributions to theoretical physics, and “providing critical insight into the evolution Lane of Boston University, together with especially for the remarkable ideas that they of nuclear structure with varying proton and Estia Eichten and Chris Quigg of Fermilab. -

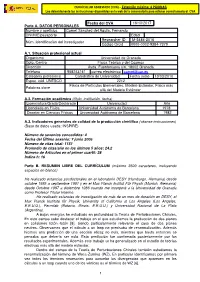

CVN De FECYT Fecha Del Documento: 04/07/2019 V 1.4.0 6Deca78505f8d048887e1fd5285c6c36

CURRÍCULUM ABREVIADO (CVA) – Extensión máxima: 4 PÁGINAS Lea detenidamente las instrucciones disponibles en la web de la convocatoria para rellenar correctamente el CVA Fecha del CVA 16/10/2017 Parte A. DATOS PERSONALES Nombre y apellidos Cornet Sánchez del Águila, Fernando DNI/NIE/pasaporte Edad Researcher ID M-5484-2016 Núm. identificación del investigador Código Orcid 0000-0002-9384-7379 A.1. Situación profesional actual Organismo Universidad de Granada Dpto./Centro Física Teórica y del Cosmos Dirección Avda. Fuentenueva s/n, 18002 Granada Teléfono 958243161 correo electrónico [email protected] Categoría profesional Catedrático de Universidad Fecha inicio 10/03/2010 Espec. cód. UNESCO 2212 Física de Partículas Elementales, Modelo Estándar, Física más Palabras clave allá del Modelo Estándar A.2. Formación académica (título, institución, fecha) Licenciatura/Grado/Doctorado Universidad Año Licenciado en Física Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 1978 Docotor en Ciencias Físicas Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 1982 A.3. Indicadores generales de calidad de la producción científica (véanse instrucciones) (Base de datos usada: INSPIRE) Número de sexenios concedidos: 4 Fecha del Último sexenio: 7 junio 2006 Número de citas total: 1151 Promedio de citas/año en los últimos 5 años: 24.2 Número de Artículos en el primer cuartil: 28 Índice h: 16 Parte B. RESUMEN LIBRE DEL CURRÍCULUM (máximo 3500 caracteres, incluyendo espacios en blanco) He realizado estancias posdoctorales en el laboratorio DESY (Hamburgo, Alemania) desde octubre 1985 a septiembre 1987 y en el Max Planck Institut Für Physik (Munich, Alemania) desde Octubre 1987 a diciembre 1988 cuando me incorporé a la Universidad de Granada como Profesor Titular Interino. -

2012 Annual Report American Physical Society N G E E T I S M I C I F T N E I

AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY TM A L R E N U P O N R A T 2 1 0 2 TM THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY STRIVES TO Be the leading voice for physics and an authoritative source of physics information for the advancement of physics and the benefit of humanity Collaborate with national scientific societies for the advancement of science, science education, and the science community Cooperate with international physics societies to promote physics, to support physicists worldwide, and to foster international collaboration Have an active, engaged, and diverse membership, and support the activities of its units and members. Cover images: top: Real CMS proton-proton collision events in which 4 high energy electrons (green lines and red towers) are observed. The event shows characteristics expected from the decay of a Higgs boson but is also consistent with background Standard Model physics processes [T. McCauley et al., CERN, (2012)] Bottom, left to right, a: Vortices on demand in multicomponent Bose-Einstein condensates [R. Zamora-Zamora, et al., Phys. Rev. A 86, 053624 (2012)] b: Differences between emission patterns and internal modes of optical resonators [S. Creagh et al., Phys. Rev. E 85, 015201 (2012)] c: Magnetic field lines of a pair of Nambu monopoles [R. C. Silvaet al., Phys. Rev. B 87, 014414 (2013)] d: Scaling behavior and beyond equilibrium in the hexagonal manganites [S. M. Griffinet al., Phys. Rev. X 2, 041022 (2012)] Page 2: Effect of solutal Marangoni convection on motion, coarsening, and coalescence of droplets in a monotectic system [F. Wang et al., Phys. Rev. E 86, 066318 (2012)] Page 3: Collective excitations of quasi-two-dimensional trapped dipolar fermions: Transition from collisionless to hydrodynamic regime [M.