In Leon's Company, It Seemed That Anything Might Be Possible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unrestricted Immigration and the Foreign Dominance Of

Unrestricted Immigration and the Foreign Dominance of United States Nobel Prize Winners in Science: Irrefutable Data and Exemplary Family Narratives—Backup Data and Information Andrew A. Beveridge, Queens and Graduate Center CUNY and Social Explorer, Inc. Lynn Caporale, Strategic Scientific Advisor and Author The following slides were presented at the recent meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. This project and paper is an outgrowth of that session, and will combine qualitative data on Nobel Prize Winners family histories along with analyses of the pattern of Nobel Winners. The first set of slides show some of the patterns so far found, and will be augmented for the formal paper. The second set of slides shows some examples of the Nobel families. The authors a developing a systematic data base of Nobel Winners (mainly US), their careers and their family histories. This turned out to be much more challenging than expected, since many winners do not emphasize their family origins in their own biographies or autobiographies or other commentary. Dr. Caporale has reached out to some laureates or their families to elicit that information. We plan to systematically compare the laureates to the population in the US at large, including immigrants and non‐immigrants at various periods. Outline of Presentation • A preliminary examination of the 609 Nobel Prize Winners, 291 of whom were at an American Institution when they received the Nobel in physics, chemistry or physiology and medicine • Will look at patterns of -

Old Soldiers by Michael Riordan

Old soldiers by Michael Riordan Twenty years ago this month, an this deep inelastic region in excru experiment began at the Stanford ciating detail, the new quark-parton Linear Accelerator Center in Cali picture of a nucleon's innards fornia that would eventually redraw gradually took a firmer and firmer the map of high energy physics. hold upon the particle physics com In October 1967, MIT and SLAC munity. These two massive spec physicists started shaking down trometers were our principal 'eyes' their new 20 GeV spectrometer; into the new realm, by far the best by mid-December they were log ones we had until more powerful ging electron-proton scattering in muon and neutrino beams became the so-called deep inelastic region available at Fermilab and CERN. where the electrons probed deep They were our Geiger and Marsd- inside the protons. The huge ex en, reporting back to Rutherford cess of scattered electrons they the detailed patterns of ricocheting encountered there-about ten times projectiles. Through their magnetic the expected rate-was later inter lenses we 'observed' quarks for preted as evidence for pointlike, the very first time, hard 'pits' inside fractionally charged objects inside hadrons. the proton. These two goliaths stood reso Michael Riordan (above) did The quarks we take for granted lutely at the front as a scientific research using the 8 GeV today were at best 'mathematical' revolution erupted all about them spectrometer at SLAC as an entities in 1967 - if one allowed during the late 1960s and early MIT graduate student during them any true existence at all. -

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox”

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox” AAPT 2011 Winter Meeting Jacksonville, FL January 10, 2011 H. Frederick Dylla American Institute of Physics Steven T. Corneliussen Jefferson Lab Outline • Rutherford's call for inventing accelerators ("million volts in a soap box") • Newton, Franklin and Jefferson: Notable prefiguring of Rutherford's call • Rutherfords's discovery: The atomic nucleus and a new experimental method (scattering) • A century of particle accelerators AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators 1911 – Rutherford discovered the atom’s nucleus • Revolutionized study of the submicroscopic realm • Established method of making inferences from particle scattering 1927 – Anniversary Address of the President of the Royal Society • Expressed a long-standing “ambition to have available for study a copious supply of atoms and electrons which have an individual energy far transcending that of the alpha and beta particles” available from natural sources so as to “open up an extraordinarily interesting field of investigation.” AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s wish: “A million volts in a soapbox” Spurred the invention of the particle accelerator, leading to: • Rich fundamental understanding of matter • Rich understanding of astrophysical phenomena • Extraordinary range of particle-accelerator technologies and applications AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 From Newton, Jefferson & Franklin to Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators Isaac Newton, 1717, foreseeing something like quarks and the nuclear strong force: “There are agents in Nature able to make the particles of bodies stick together by very strong attractions. And it is the business of Experimental Philosophy to find them out. -

Quantum Mechanics Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD)

Quantum Mechanics_quantum chromodynamics (QCD) In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is a theory ofstrong interactions, a fundamental forcedescribing the interactions between quarksand gluons which make up hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type of Quantum field theory called a non- abelian gauge theory with symmetry group SU(3). The QCD analog of electric charge is a property called 'color'. Gluons are the force carrier of the theory, like photons are for the electromagnetic force in quantum electrodynamics. The theory is an important part of the Standard Model of Particle physics. A huge body of experimental evidence for QCD has been gathered over the years. QCD enjoys two peculiar properties: Confinement, which means that the force between quarks does not diminish as they are separated. Because of this, when you do split the quark the energy is enough to create another quark thus creating another quark pair; they are forever bound into hadrons such as theproton and the neutron or the pion and kaon. Although analytically unproven, confinement is widely believed to be true because it explains the consistent failure of free quark searches, and it is easy to demonstrate in lattice QCD. Asymptotic freedom, which means that in very high-energy reactions, quarks and gluons interact very weakly creating a quark–gluon plasma. This prediction of QCD was first discovered in the early 1970s by David Politzer and by Frank Wilczek and David Gross. For this work they were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics. There is no known phase-transition line separating these two properties; confinement is dominant in low-energy scales but, as energy increases, asymptotic freedom becomes dominant. -

Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame 2001

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME 2001 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Clarence N. Wood Mayor Chair/Commissioner Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues William W. Greaves Laura A. Rissover Director/Community Liaison Chairperson Ó 2001 Hall of Fame Committee. All rights reserved. COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, 3rd Floor Chicago, Illinois 60610 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) Www.GLHallofFame.org 1 2 3 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and our country are made aware of the contributions of Chicago's lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate homophobic bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of people of the LGBT communities, their organizations, and their friends, as well as their contributions to their communities and to the city of Chicago. This is a unique tribute to dedicated individuals and organizations whose services have improved the quality of life for all of Chicago's citizens. -

Date: To: September 22, 1 997 Mr Ian Johnston©

22-SEP-1997 16:36 NOBELSTIFTELSEN 4& 8 6603847 SID 01 NOBELSTIFTELSEN The Nobel Foundation TELEFAX Date: September 22, 1 997 To: Mr Ian Johnston© Company: Executive Office of the Secretary-General Fax no: 0091-2129633511 From: The Nobel Foundation Total number of pages: olO MESSAGE DearMrJohnstone, With reference to your fax and to our telephone conversation, I am enclosing the address list of all Nobel Prize laureates. Yours sincerely, Ingr BergstrSm Mailing address: Bos StU S-102 45 Stockholm. Sweden Strat itddrtSMi Suircfatan 14 Teleptelrtts: (-MB S) 663 » 20 Fsuc (*-«>!) «W Jg 47 22-SEP-1997 16:36 NOBELSTIFTELSEN 46 B S603847 SID 02 22-SEP-1997 16:35 NOBELSTIFTELSEN 46 8 6603847 SID 03 Professor Willis E, Lamb Jr Prof. Aleksandre M. Prokhorov Dr. Leo EsaJki 848 North Norris Avenue Russian Academy of Sciences University of Tsukuba TUCSON, AZ 857 19 Leninskii Prospect 14 Tsukuba USA MSOCOWV71 Ibaraki Ru s s I a 305 Japan 59* c>io Dr. Tsung Dao Lee Professor Hans A. Bethe Professor Antony Hewlsh Department of Physics Cornell University Cavendish Laboratory Columbia University ITHACA, NY 14853 University of Cambridge 538 West I20th Street USA CAMBRIDGE CB3 OHE NEW YORK, NY 10027 England USA S96 014 S ' Dr. Chen Ning Yang Professor Murray Gell-Mann ^ Professor Aage Bohr The Institute for Department of Physics Niels Bohr Institutet Theoretical Physics California Institute of Technology Blegdamsvej 17 State University of New York PASADENA, CA91125 DK-2100 KOPENHAMN 0 STONY BROOK, NY 11794 USA D anni ark USA 595 600 613 Professor Owen Chamberlain Professor Louis Neel ' Professor Ben Mottelson 6068 Margarldo Drive Membre de rinstitute Nordita OAKLAND, CA 946 IS 15 Rue Marcel-Allegot Blegdamsvej 17 USA F-92190 MEUDON-BELLEVUE DK-2100 KOPENHAMN 0 Frankrike D an m ar k 599 615 Professor Donald A. -

Chris Quigg · Physicist

CHRIS QUIGG · PHYSICIST Theoretical Physics Department 1218 Howard Circle Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Wheaton, Illinois 60187 P.O. Box 500, Batavia, Illinois 60510 +1 630.840.3578 +1 630.660.1370 [email protected] [email protected] lutece.fnal.gov chrisquigg.com Born 15 December 1944 in Bainbridge, Maryland, USA · United States citizen PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Theoretical Physics Department, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, 1974–present; Distinguished Scientist Emeritus, 2017–present; Department Head, 1977–1987. Superconducting Super Collider Central Design Group Deputy Director for Operations, 1987–1989. Institute for Theoretical Physics, State University of New York, Stony Brook Associate Professor, 1974; Assistant Professor, 1971–4; Research Associate, 1970–1. SECONDARY AFFILIATION University of Chicago Department of Physics and Enrico Fermi Institute, Professor (part-time), 1982–1991; Professorial Lecturer, 1978–1982; Visiting Scholar, Enrico Fermi Institute, 1974–1978. EDUCATION Yale University · B.S., Physics, 1966. Magna cum laude, with honors with exceptional distinction in physics. University of California, Berkeley · Ph.D., Physics, 1970; Thesis advisor, J. D. Jackson. Two-Reggeon-Exchange Contributions to Scattering Amplitudes at High Energies. HONORS AND AWARDS Phi Beta Kappa, 1966. Sigma Xi, 1966. De Forest Pioneers Prize (Yale University), 1966. Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, 1966–1967. HONORS AND AWARDS continued University of California Science Fellowship, 1967–1970. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Research Fellowship, 1974–1978. Fellow of the American Physical Society, 1983, for his numerous significant contributions in the theory of elementary particle physics and high energy collisions. His activities span work on multiparticle production, production and decay of intermediate bosons, and signatures of charmed mesons. One of the many notable contributions is the work on Quarkonium states, noted for lucid and seminal nonrelativistic quantum me- chanics application. -

Advanced Information on the Nobel Prize in Physics, 5 October 2004

Advanced information on the Nobel Prize in Physics, 5 October 2004 Information Department, P.O. Box 50005, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 8 673 95 00, Fax: +46 8 15 56 70, E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.kva.se Asymptotic Freedom and Quantum ChromoDynamics: the Key to the Understanding of the Strong Nuclear Forces The Basic Forces in Nature We know of two fundamental forces on the macroscopic scale that we experience in daily life: the gravitational force that binds our solar system together and keeps us on earth, and the electromagnetic force between electrically charged objects. Both are mediated over a distance and the force is proportional to the inverse square of the distance between the objects. Isaac Newton described the gravitational force in his Principia in 1687, and in 1915 Albert Einstein (Nobel Prize, 1921 for the photoelectric effect) presented his General Theory of Relativity for the gravitational force, which generalized Newton’s theory. Einstein’s theory is perhaps the greatest achievement in the history of science and the most celebrated one. The laws for the electromagnetic force were formulated by James Clark Maxwell in 1873, also a great leap forward in human endeavour. With the advent of quantum mechanics in the first decades of the 20th century it was realized that the electromagnetic field, including light, is quantized and can be seen as a stream of particles, photons. In this picture, the electromagnetic force can be thought of as a bombardment of photons, as when one object is thrown to another to transmit a force. -

The Strong and Weak Senses of Theory-Ladenness of Experimentation: Theory-Driven Versus Exploratory Experiments in the History of High-Energy Particle Physics

[Accepted for Publication in Science in Context] The Strong and Weak Senses of Theory-Ladenness of Experimentation: Theory-Driven versus Exploratory Experiments in the History of High-Energy Particle Physics Koray Karaca University of Wuppertal Interdisciplinary Centre for Science and Technology Studies (IZWT) University of Wuppertal Gaußstr. 20 42119 Wuppertal, Germany [email protected] Argument In the theory-dominated view of scientific experimentation, all relations of theory and experiment are taken on a par; namely, that experiments are performed solely to ascertain the conclusions of scientific theories. As a result, different aspects of experimentation and of the relation of theory to experiment remain undifferentiated. This in turn fosters a notion of theory- ladenness of experimentation (TLE) that is too coarse-grained to accurately describe the relations of theory and experiment in scientific practice. By contrast, in this article, I suggest that TLE should be understood as an umbrella concept that has different senses. To this end, I introduce a three-fold distinction among the theories of high-energy particle physics (HEP) as background theories, model theories and phenomenological models. Drawing on this categorization, I contrast two types of experimentation, namely, “theory-driven” and “exploratory” experiments, and I distinguish between the “weak” and “strong” senses of TLE in the context of scattering experiments from the history of HEP. This distinction enables to identify the exploratory character of the deep-inelastic electron-proton scattering experiments— performed at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) between the years 1967 and 1973—thereby shedding light on a crucial phase of the history of HEP, namely, the discovery of “scaling”, which was the decisive step towards the construction of quantum chromo-dynamics (QCD) as a gauge theory of strong interactions. -

Intera T on Po* I

t"-* t i *0n * Events and Happenings I Intera* t on Po*I September 1997 Vol. 8. No. 9 Lab Strategic Plans Outlined HOW ARE WE DOING? Where are we going? How can we improve? Those were the basic questions of DOE officials who visited SLAC last month for the On-Site Review. Every two years SLAC has an opportunity to lay out our long- term plans to the DOE for their comment. SLAC Director Burton Richter began the meeting with a summary of strategic issues such as the need for budget increases, the continuous improvement of health and safety, and the renovation of our aging infrastructure. Martha Krebs, Director of DOE's Office of Energy Research (DOE-ER) praised SLAC and Richter's leadership in the area of safety, citing specificallyx J the site-wide safetyJ stand downs which started two years ago. "This lab is a model Summer interns met with DOE officials to discuss the for others in terms of involving the entire staff importance of research opportunities for and being proactive in safety issues," commented undergraduates. (I to r) Top row: Antoinette Joseph Krebs. (DOE), Helen Quinn (SLAC), Cicely Mitchell, Krebs and her staff were briefed on future Jaimme York, Carlos Figueroa (director of the directions of high energy physics and synchrotron summer intern program), Erich Caulfield, and Sam radiation. "I've been getting the word from Rodriguez (DOE). Bottom Row (I to r) Ivonne Mosquera, Garth White, Martha Krebs (DOE), and LnristlW7-_ __ _ rlacco.T71. _ _ _. others that SSRL is an outstanding program in 0 respect to user satisfaction and service," said 0 Krebs. -

Sensitivity Physics. D KAONS, Or

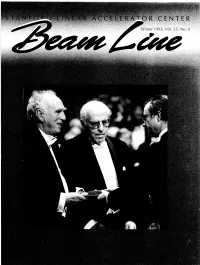

A PERIODICAL OF PARTICLE PHYSICS WINTER 1995 VOL. 25, NUMBER 4 Editors RENE DONALDSON, BILL KIRK Contributing Editor MICHAEL RIORDAN Editorial Advisory Board JAMES BJORKEN, GEORGE BROWN, ROBERT N. CAHN, DAVID HITLIN, JOEL PRIMACK, NATALIE ROE, ROBERT SIEMANN Illustrations page 4 TERRY ANDERSON Distribution CRYSTAL TILGHMAN The Beam Line is published quarterly by the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, PO Box 4349, Stanford, CA 94309. Telephone: (415) 926-2585 INTERNET: [email protected] FAX: (415) 926-4500 Issues of the Beam Line are accessible electronically on uayc ou the World Wide Web at http://www.slac.stanford.edu/ pubs/beamline/beamline.html SLAC is operated by Stanford University under contract with the U.S. Department of Energy. The opinions of the authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Cover: Martin Perl (left) and Frederick Reines (center) receive the 1995 Nobel Prize in physics from His Majesty the King of Sweden at the awards ceremony last December. (Photograph courtesy of Joseph Peri) Printed on recycled paper tj) . CONTENTS FEATURES "We conclude that the signature e-/. events cannot be explained either by the production and decay of any presently known particles 4 Discovery of the Tau or as coming from any of the well- THE ROLE OF MOTIVATION & understood interactions which can TECHNOLOGY IN EXPERIMENTAL conventionally lead to an e and a PARTICLE PHYSICS gu in the final state. A possible ex- One of this year's Nobel Prize in physics planation for these events is the recipients describes the discovery production and decay of a pair of of the tau lepton in his 1975 new particles, each having a mass SLAC experiment. -

Fall 2011 Contents

A FORMULA INSIDE: Lettuce Entertain You’s Bob Wattel P 6 FOR SUCCESS Meet the Met Quartet P 38 Professor David Faris on Roosevelt’s College of Pharmacy welcomes its inaugural class. PAGE 26 social media in Egypt P 44 ROOSEVELT REVIEW | FALL 2011 CONTENTS CREATING A LEGACY Grant Pick (1947-2005) food or money, to “The Morning Mouth” about controversial radio announcer Mancow Muller. When Pick spoke to journalism classes, students would often ask, “Where is the news peg?” to his stories. He would reply, “There is no news peg. The people are the news.” Nineteen of his stories are collected in the post- humous 2008 book The People Are the News: Grant Pick’s Chicago Stories, edited by his son and laced with photos by his wife. In his introduction to the book, author Alex Kotlowitz writes: “Grant Pick is a Chicago treasure.” He was “... someone who found poetry in the quotidian, who saw the Roosevelt University is pleased to announce the extraordinary in the ordinary.” Grant Pick Endowed Scholarship in Journalism. This scholarship was established at Roosevelt The father of John and Emily, Pick was firmly by Pick’s wife, Kathy Richland Pick, an accom- committed to public education and school reform. plished photojournalist and portrait photographer He was active in the Chicago Public Schools’ local whose photos often accompanied Pick’s articles councils and wrote about education and school and were the visual distillation of his writing. reform for The Reader and Catalyst. Grant Pick (BA, ’70) was a well-known figure Kathy Pick said: “Grant had an insatiable curios- among Chicago journalists.