Managing Vegetation for Agronomic and Ecological Benefits in California Nut Orchards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomology) 1968, Ph.D

RING T. CARDÉ a. Professional Preparation Tufts University B.S. (Biology), 1966 Cornell University M.S. (Entomology) 1968, Ph.D. (Entomology) 1971 New York State Agricultural Postdoctoral Associate, 1971-1975 Experiment Station at Geneva (Cornell University) b. Appointments and Professional Activities Positions Held 1996-present Distinguished Professor & Alfred M. Boyce Endowed Chair in Entomology, University of California, Riverside 2011 Visiting Professor, Swedish Agricultural University (SLU), Alnarp 2003-2009 Chair, Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside 1989-1996 Distinguished University Professor, University of Massachusetts 1988 Visiting Scientist, Wageningen University 1984-1989 Professor of Entomology, University of Massachusetts 1981-1987; 1993-1995 Head, Entomology, University of Massachusetts 1981-1984 Associate Professor of Entomology, University of Massachusetts 1978-1981 Associate Professor of Entomology, Michigan State University 1975-1978 Assistant Professor of Entomology, Michigan State University Honors and Awards (selected) Certificate of Distinction for Outstanding Achievements, International Congress of Entomology, 2016 President, International Society of Chemical Ecology, 2012-2013 Jan Löfqvist Grant, Royal Academy of Natural Sciences, Medicine and Technology, Sweden, 2011 Silver Medal, International Society of Chemical Ecology, 2009 Awards for “Encyclopedia of Insects” include: • “Most Outstanding Single-Volume Reference in Science”, Association of American Publishers 2003 • “Outstanding -

Integrated Pest Managemnent ~~R, Him4 T

Integrated Pest Managemnent ~~r, him4 t. I~ f4 ,..,.. 9,.. i Ulf U k gA, fi 0I,. i f. Council on Environmental Quality Integrated Pest Management December 1979 Written by Dale G. Bottrell K' Preface For many centuries human settlements, both agricultural and urban, have had to contend with a variety of unwanted and sometimes harmful insects, weeds, microorgan isms, rodents, and other organisms-collectively, "pests." During the use of chemical last four decades, p'sticides has become the predominant method of controlling these unwanted organisms in much of the world, including the United States. synthetic Production of organic pesticides in this countty alone has increased from less than 500,000 pounds in 1951 to an estimated 1.4 billion pounds in 1977. A decade ago, there was rising public concern over the accumulation pesticides of in the environment, with resulting adverse effects on some fish and wildlife populations and hazards to human health. In response to the problems, the Council on Environmental Quality undertook a study of alternative methods Integrated of pest control. Pest Management, published in 1972, stimulated increased national and international interest in integrated pest management-IPM-as an cient, economically effi environmentally preferable approach to pest control, particularly in agriculture. Since then much has been learned about the effects of pesticides, and programs have been developed which put the concept of IPM into practice. began a In 1976 the Council more comprehensive review of integrated pest management in the United States, giving attention to the potential for IPM programs in forestry, public health, urban systems and as well as in agriculture. -

Biological Pest Control

■ ,VVXHG LQ IXUWKHUDQFH RI WKH &RRSHUDWLYH ([WHQVLRQ :RUN$FWV RI 0D\ DQG -XQH LQ FRRSHUDWLRQ ZLWK WKH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV 'HSDUWPHQWRI$JULFXOWXUH 'LUHFWRU&RRSHUDWLYH([WHQVLRQ8QLYHUVLW\RI0LVVRXUL&ROXPELD02 ■DQHTXDORSSRUWXQLW\$'$LQVWLWXWLRQ■■H[WHQVLRQPLVVRXULHGX AGRICULTURE Biological Pest Control ntegrated pest management (IPM) involves the use of a combination of strategies to reduce pest populations Steps for conserving beneficial insects Isafely and economically. This guide describes various • Recognize beneficial insects. agents of biological pest control. These strategies include judicious use of pesticides and cultural practices, such as • Minimize insecticide applications. crop rotation, tillage, timing of planting or harvesting, • Use selective (microbial) insecticides, or treat selectively. planting trap crops, sanitation, and use of natural enemies. • Maintain ground covers and crop residues. • Provide pollen and nectar sources or artificial foods. Natural vs. biological control Natural pest control results from living and nonliving Predators and parasites factors and has no human involvement. For example, weather and wind are nonliving factors that can contribute Predator insects actively hunt and feed on other insects, to natural control of an insect pest. Living factors could often preying on numerous species. Parasitic insects lay include a fungus or pathogen that naturally controls a pest. their eggs on or in the body of certain other insects, and Biological pest control does involve human action and the young feed on and often destroy their hosts. Not all is often achieved through the use of beneficial insects that predacious or parasitic insects are beneficial; some kill the are natural enemies of the pest. Biological control is not the natural enemies of pests instead of the pests themselves, so natural control of pests by their natural enemies; host plant be sure to properly identify an insect as beneficial before resistance; or the judicious use of pesticides. -

Folk Taxonomy, Nomenclature, Medicinal and Other Uses, Folklore, and Nature Conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3

Ulicsni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:47 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7 RESEARCH Open Access Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe - folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3 Abstract Background: There is scarce information about European folk knowledge of wild invertebrate fauna. We have documented such folk knowledge in three regions, in Romania, Slovakia and Croatia. We provide a list of folk taxa, and discuss folk biological classification and nomenclature, salient features, uses, related proverbs and sayings, and conservation. Methods: We collected data among Hungarian-speaking people practising small-scale, traditional agriculture. We studied “all” invertebrate species (species groups) potentially occurring in the vicinity of the settlements. We used photos, held semi-structured interviews, and conducted picture sorting. Results: We documented 208 invertebrate folk taxa. Many species were known which have, to our knowledge, no economic significance. 36 % of the species were known to at least half of the informants. Knowledge reliability was high, although informants were sometimes prone to exaggeration. 93 % of folk taxa had their own individual names, and 90 % of the taxa were embedded in the folk taxonomy. Twenty four species were of direct use to humans (4 medicinal, 5 consumed, 11 as bait, 2 as playthings). Completely new was the discovery that the honey stomachs of black-coloured carpenter bees (Xylocopa violacea, X. valga)were consumed. 30 taxa were associated with a proverb or used for weather forecasting, or predicting harvests. Conscious ideas about conserving invertebrates only occurred with a few taxa, but informants would generally refrain from harming firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus), field crickets (Gryllus campestris) and most butterflies. -

Pheromone Trap Catch of Harmful Microlepidoptera Species in Connection with the Chemical Air Pollutants

International Journal of Research in Environmental Science (IJRES) Volume 2, Issue 1, 2016, PP 1-10 ISSN 2454-9444 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9444.0201001 www.arcjournals.org Pheromone Trap Catch of Harmful Microlepidoptera Species in Connection with the Chemical Air Pollutants L. Nowinszky1, J. Puskás1, G. Barczikay2 1University of West Hungary Savaria University centre, Szombathely, Károlyi Gáspár Square 4 2County Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén Agricultural Office of Plant Protection and Soil Conservation Directorate, Bodrogkisfalud, Vasút Street. 22 [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In this study, seven species of Microlepidoptera pest pheromone trap collection presents the results of the everyday function of the chemical air pollutants (SO2, NO, NO2, NOx, CO, PM10, O3). Between 2004 and 2013 Csalomon type pheromone traps were operating in Bodrogkisfalud (48°10’N; 21°21E; Borsod-Abaúj- Zemplén County, Hungary, Europe). The data were processed of following species: Spotted Tentiform Leafminer (Phyllonorycter blancardella Fabricius, 1781), Hawthorn Red Midged Moth (Phyllonorycter corylifoliella Hübner, 1796), Peach Twig Borer (Anarsia lineatella Zeller, 1839), European Vine Moth (Lobesia botrana Denis et Schiffermüller, 1775), Plum Fruit Moth (Grapholita funebrana Treitschke, 1846), Oriental Fruit Moth (Grapholita molesta Busck, 1916) and Codling Moth (Cydia pomonella Linnaeus, 1758). The relation is linear, logarithmic and polynomial functions can be characterized. Keywords: Microlepidoptera, pests, pheromone traps, air pollution 1. INTRODUCTION Since the last century, air pollution has become a major environmental problem, mostly over large cities and industrial areas (Cassiani et al. 2013). It is natural that the air pollutant chemicals influence the life phenomena of insects, such as flight activity as well. -

Biological Control and Agricultural Modernization: Towards Resolution of Some Contradictions

Agriculture and Human Values 14: 303±310, 1997. c 1997 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Biological control and agricultural modernization: Towards resolution of some contradictions Miguel A. Altieri, Peter M. Rosset and Clara I. Nicholls ESPM-Division of Insect Biology, University of California, Berkeley, USA Accepted in revised form June 12, 1997 Abstract. An emergent contradiction in the contemporary development of biological control is that of the prevalence of the substitution of periodic releases of natural enemies for chemical insecticides and the dominance of biotechnologically developed transgenic crops. Input substitution leaves in place the monoculture nature of agroecosystems, which in itself is a key factor in encouraging pest problems. Biotechnology, now under corporate control, creates more dependency and can potentially lead to Bt resistance, thus excluding from the market a key biopesticide. Approaches for putting back biological control into the hands of farmers (from artesanal biotechnology for grassroots biopesticide production Cuban style to farmer-to-farmer IPM networks, etc.) have been developed as a way to create a farmer centered approach to biological control Key words: Biological control, Environmental policy, IPM programs Miguel A. Altieri is Associate Professor, University of California, Berkeley. General Coordinator of the UNDP sponsored program Sustainable Agriculture Networking and Extension (SANE) promoting capacity building in agro- ecology in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Chairman of the CGiAR-NGO committee to encourage partnerships among NGOs and International Agricultural Research Centers to scale-up agroecological strategies. Peter M. Rosset is the Executive Director of Food First ± The Institute for Food and Development Policy, based in Oakland, California. -

Plant Extracts As Biological Control Agents Jagessar RC* Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Guyana, South America

www.biogenericpublishers.com Article Type: Review Article Received: 07/10/2020 Published: 09/11/2020 DOI: 10.46718/JBGSR.2020.05.000123 Plant Extracts as Biological Control Agents Jagessar RC* Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Guyana, South America *Corresponding author: Jagessar Rc, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Guyana, South America Abstract Over the years, synthetic pesticides have been used by farmers to control and eradicate pests, with a view to increase crop production and productivity. However, scientists have found that synthetic pesticides are detrimental to the environment, are expensive, non-biodegradable and can increase pest resistivity. To continue to mitigate pest control in crops, there has been the use of organic pesticides as biological controllable agents against pests in crops. Such a practice is easier, less costly, eco and environmentally friendly and eliminate pesticide residues etc and make agriculture, agricultural products and market sustainable, and increase food security around the globe. The use of plant extracts as bio-controlling agents or “green agrochemicals” should be intensified, so that there is a gradual phasing out of synthetic organic pesticides. This article, gives a mini review of the use of plant extracts as natural pesticides or biological control agents against disease inducing pests that destroy agricultural crops. Keywords: synthetic pesticides; crop production and productivity; organic pesticides; biological control. -

Weed Biocontrol: Extended Abstracts from the 1997 Interagency Noxious-Weed Symposium

Weed Biocontrol: Extended Abstracts from the 1997 Interagency Noxious-Weed Symposium Dennis Isaacson Martha H. Brookes Technical Coordinators U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team Morgantown, WV and Oregon Department of Agriculture Salem, OR June 1999 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many of the tasks of organizing a symposium such as this — and there are many — are not obvious, and, if they are handled well, the effort that goes into them can easily be overlooked. Sherry Kudna of the Oregon Department of Agriculture Weed Control staff managed most of the arrangements and took care of many, many details, which helped the symposium run smoothly. We truly appreciate her many contributions. We also acknowledge the contributions of the presenters. They not only organized their own presentations and manuscripts, but also assisted with reviewing drafts of each other’s papers in the proceedings. Several of the presenters also covered their own expenses. Such dedication speaks well of their commitment to improving the practice of weed biocontrol. Both the Oregon State Office of the Bureau of Land Management and the USDA Forest Service made major contributions to supporting the symposium. Although several individuals from both organizations provided assistance, we especially note the encouragement and advice of Bob Bolton, Oregon Bureau of Land Management Weed Control Coordinator, and the willingness to help and financial support for publishing this document from Richard C. Reardon, Biocontrol/Biopesticides Program Manager, USDA Forest Service's Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, WV. We thank Tinathan Coger for layout and design and Patricia Dougherty for printing advice and coordination of the manuscript We also thank Barbra Mullin, Montana State Department of Agriculture, who delivered the keynote address; Tami Lowry, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Corvallis, who helped format the document; and Eric Coombs, who provided the photographs of weeds and agents that convey the concepts of weed biocontrol. -

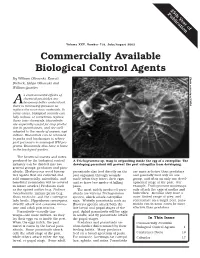

Commercially Available Biocontrol Agents

25th Year of Publication Volume XXV, Number 7/8, July/August 2003 Commercially Available Biological Control Agents By William Olkowski, Everett Photo courtesy of USDA Dietrick, Helga Olkowski and William Quarles s environmental effects of chemical pesticides are A becoming better understood, there is increasing pressure to replace the more toxic materials. In some cases, biological controls can help reduce, or sometimes replace, these toxic chemicals. Biocontrols are especially useful for crop produc- tion in greenhouses, and are well adapted to the needs of organic agri- culture. Biocontrols can be released in parks and landscapes to relieve pest pressures in municipal IPM pro- grams. Biocontrols also have a home in the backyard garden. The beneficial insects and mites produced by the biological control A Trichogramma sp. wasp is ovipositing inside the egg of a caterpillar. The industry can be divided into two developing parasitoid will prevent the pest caterpillar from developing. general groups: predators and para- sitoids. [Herbivorous weed biocon- parasitoids also feed directly on the are more selective than predators trol agents that are collected and pest organism through wounds and generally feed only on one sold commercially, microbials, and made when they insert their eggs, group, and often on only one devel- beneficial nematodes will be covered and so have two modes of killing opmental stage of the pest. For in future articles.] Predators such pests. example, Trichogramma miniwasps as the spined soldier bug, Podisus The most widely produced para- only attack the eggs of moths and maculiventris, minute pirate bug, sitoids are various Trichogramma butterflies. Because they have a Orius tristicolor, and the convergent species, which attack caterpillar more limited range of prey, and lady beetle, Hippodamia convergens, eggs. -

1 Modern Threats to the Lepidoptera Fauna in The

MODERN THREATS TO THE LEPIDOPTERA FAUNA IN THE FLORIDA ECOSYSTEM By THOMSON PARIS A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 2011 Thomson Paris 2 To my mother and father who helped foster my love for butterflies 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I thank my family who have provided advice, support, and encouragement throughout this project. I especially thank my sister and brother for helping to feed and label larvae throughout the summer. Second, I thank Hillary Burgess and Fairchild Tropical Gardens, Dr. Jonathan Crane and the University of Florida Tropical Research and Education center Homestead, FL, Elizabeth Golden and Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park, Leroy Rogers and South Florida Water Management, Marshall and Keith at Mack’s Fish Camp, Susan Casey and Casey’s Corner Nursery, and Michael and EWM Realtors Inc. for giving me access to collect larvae on their land and for their advice and assistance. Third, I thank Ryan Fessendon and Lary Reeves for helping to locate sites to collect larvae and for assisting me to collect larvae. I thank Dr. Marc Minno, Dr. Roxanne Connely, Dr. Charles Covell, Dr. Jaret Daniels for sharing their knowledge, advice, and ideas concerning this project. Fourth, I thank my committee, which included Drs. Thomas Emmel and James Nation, who provided guidance and encouragement throughout my project. Finally, I am grateful to the Chair of my committee and my major advisor, Dr. Andrei Sourakov, for his invaluable counsel, and for serving as a model of excellence of what it means to be a scientist. -

Dr. Frank G. Zalom

Award Category: Lifetime Achievement The Lifetime Achievement in IPM Award goes to an individual who has devoted his or her career to implementing IPM in a specific environment. The awardee must have devoted their career to enhancing integrated pest management in implementation, team building, and integration across pests, commodities, systems, and disciplines. New for the 9th International IPM Symposium The Lifetime Achievement winner will be invited to present his or other invited to present his or her own success story as the closing plenary speaker. At the same time, the winner will also be invited to publish one article on their success of their program in the Journal of IPM, with no fee for submission. Nominator Name: Steve Nadler Nominator Company/Affiliation: Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis Nominator Title: Professor and Chair Nominator Phone: 530-752-2121 Nominator Email: [email protected] Nominee Name of Individual: Frank Zalom Nominee Affiliation (if applicable): University of California, Davis Nominee Title (if applicable): Distinguished Professor and IPM specialist, Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis Nominee Phone: 530-752-3687 Nominee Email: [email protected] Attachments: Please include the Nominee's Vita (Nominator you can either provide a direct link to nominee's Vita or send email to Janet Hurley at [email protected] with subject line "IPM Lifetime Achievement Award Vita include nominee name".) Summary of nominee’s accomplishments (500 words or less): Describe the goals of the nominee’s program being nominated; why was the program conducted? What condition does this activity address? (250 words or less): Describe the level of integration across pests, commodities, systems and/or disciplines that were involved. -

An Introduction to Natural Enemies for Biological Control of Pest Insects

An Introduction to Natural Biological control Enemies for Biological Control of Pest Insects Use of natural enemies to keep unwanted pest populations low Anna Fiedler, Doug Landis, Rufus Isaacs, Julianna Tuell Dept. of Entomology, Michigan State University Natural enemies Lady beetles (Coccinellidae) Predator • Predators: eat many prey • Most adults and larvae feed in a lifetime, feeding both on soft-bodied insects. These as young and as adults. may be important in aphid • Parasitoids: specialized population control. insects that develop as a • Adults are rounded, and young in one host, range in size from tiny to ¼ Scott Bauer eventually killing it. inch long. Color ranges from • Pathogens: nematodes, black to brightly colored. viruses, bacteria, fungi, • Larvae are active and protozoans. elongate with long legs, and look like tiny alligators. Mary Gardiner Soldier beetles Predaceous ground (Cantharidae) Predator beetles (Carabidae) Predator • Adults feed on nectar and pollen and • Most are predaceous on are often found at flowers. insects in and on the soil as • Some adults eat aphids, insect eggs adults and larvae. and larvae or feed on both flowers • Adults are most active at and insects. night, dark in color, with long • Adults are elongate, with red, orange, legs. or yellow and black patterns on head • Larvae are often in leaf litter and abdomen. Adults are ¼ to ¾ inch or soil and are elongate. long, with soft wing covers. Susan Ellis • Some feed on seeds and can Debbie Waters, Univ. of Georgia • Larvae are dark, flattened and reduce the number of weed elongate. Larvae feed on eggs and seeds in agricultural systems.