The UK's Ageing Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections Development Policy

Collections Development Policy Acquisition and disposal of collections Contents 1 Relationship to other relevant policies/plans of the organisation ......................................... 3 2 History of the collections ...................................................................................................... 4 3 An overview of the current collections.................................................................................. 4 4 Themes and priorities for future collecting ........................................................................... 7 5 Themes and priorities for rationalisation and disposal ........................................................... 8 6 Legal and ethical framework for acquisition and disposal of items ........................................ 9 7 Collecting policies of other museums ................................................................................... 9 8 Archival holdings .................................................................................................................. 9 9 Acquisition .......................................................................................................................... 10 10 Human Remains ................................................................................................................ 11 11 Biological and geological material ...................................................................................... 11 12 Archaeological material .................................................................................................... -

The Geffrye Museum Trust

THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009-476) Ordered By the House of Commons to be printed on 9th July 2012 HC 304 London: The Stationery Office £10.75 © The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.geffrye-museum.org.uk ISBN: 9780102977349 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2487680 07/12 21997 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST (Company Number 2476642) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR -

Zenobia Kozak Phd Thesis

=><9<@6;4 @52 =.?@! =>2?2>B6;4 @52 3A@A>2 , />6@6?5 A;6B2>?6@C 52>[email protected] 0<8820@6<;? .;1 612;@6@C 9.>72@6;4 DIQRFME 7R\EN . @LIUMU ?WFPMVVIH JRT VLI 1IKTII RJ =L1 EV VLI AQMXITUMV[ RJ ?V# .QHTIYU '%%* 3WOO PIVEHEVE JRT VLMU MVIP MU EXEMOEFOI MQ >IUIETGL-?V.QHTIYU,3WOO@IZV EV, LVVS,$$TIUIETGL"TISRUMVRT[#UV"EQHTIYU#EG#WN$ =OIEUI WUI VLMU MHIQVMJMIT VR GMVI RT OMQN VR VLMU MVIP, LVVS,$$LHO#LEQHOI#QIV$&%%'($)%+ @LMU MVIP MU STRVIGVIH F[ RTMKMQEO GRS[TMKLV @LMU MVIP MU OMGIQUIH WQHIT E 0TIEVMXI 0RPPRQU 8MGIQUI Promoting the past, preserving the future: British university heritage collections and identity marketing Zenobia Rae Kozak PhD, Museum and Gallery Studies 20, November 2007 Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………………………......3 List of Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Abstract……………………………………………………..………………………………………………………………………7 1. Introduction: the ‘crisis’ of university museums…………………………………………...8 1.1 UK reaction to the ‘crisis’…………………………………………………………………………………………………9 1.2 International reaction to the ‘crisis’…………………………………………………………………………………14 1.3 Universities, museums and collections in the UK………………………………………………………………17 1.3.1 20th-century literature review…………………………………………………………………………………19 1.4 The future of UK university museums and collections………………………………………………………24 1.4.1 Marketing university museums -

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014 includes 2014 Museum and Galleries D of Oxfordshire Competition OR SH F IR X E O O M L U I S C MC E N U U M O S C Soldiers of Oxfodshire Museum, Woodstock www.oxfordshiremuseums.org The SOFO Museum Woodstock By a winning team Architects Structural Project Services CDM Co-ordinators Engineers Management Engineers OXFORD ARCHITECTS FULL PAGE AD museums booklet ad oct10.indd 1 29/10/10 16:04:05 Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2012 Welcome to the 2012 edition of Museums or £50, there is an additional £75 Blackwell andMuseums Galleries of Oxfordshire and Galleries. You will find oftoken Oxfordshire for the most questions answered2014 detailsWelcome of to 39 the Museums 2014 edition from of everyMuseums corner and £75correctly. or £50. There is an additional £75 token for ofGalleries Oxfordshire of Oxfordshire, who are your waiting starting to welcomepoint the most questions answered correctly. Tokens you.for a journeyFrom Banbury of discovery. to Henley-upon-Thames, You will find details areAdditionally generously providedthis year by we Blackwell, thank our Broad St, andof 40 from museums Burford across to Thame,Oxfordshire explore waiting what to Oxford,advertisers and can Bloxham only be redeemed Mill, Bloxham in Blackwell. School, ourwelcome rich heritageyou, from hasBanbury to offer. to Henley-upon- I wouldHook likeNorton to thank Brewery, all our Oxfordadvertisers London whose Thames, all of which are taking part in our new generousAirport, support Smiths has of allowedBloxham us and to bring Stagecoach this Thecompetition, competition supported this yearby Oxfordshire’s has the theme famous guidewhose to you, generous and we supportvery much has hope allowed that us to Photo: K T Bruce Oxfordshirebookseller, Blackwell. -

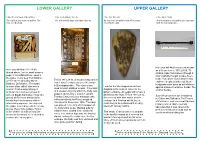

Lower Gallery Upper Gallery

LOWER GALLERY UPPER GALLERY Case 90.A ‘Games and Puzzles’ Case 14.A ‘Baby Carriers’ Case 3.B ‘Shields’ Case 49.A ‘Clubs’ Turn right at you enter the gallery. The You will find this large wall case close by. As you enter the gallery look left to cases At the entrace to the gallery turn right and case is a desktop. covering the wall. look for a desktop case. Here you will find a small club known Here you will find 1911.29.68, as a life preserver, 1911.29.66. The shown above, twelve small wooden shaft is made from baleen (though it pegs, in a cardboard box, used in was originally thought to have been the game ‘merry peg’ from Baldon- made from whale bone) and the two on-the-Green (possibly Marsh This is 1911.29.86, a wooden baby runner from Long Crendon, just over the border ends are weighted with lead. Such Baldon), Oxfordshire. This game bludgeons were used as self defence is more often called ‘nine men’s in Buckinghamshire. This runner was Look for the kite-shaped shield from used to teach children to walk. It consists against attackers’ wrists or heads. The morris’. It has a long history--it England in the nearest corner to the shaft is flexible. is known to have been played in of a wooden ring into which the baby was gallery entrance. An eagle with a halo is popped attached to a wooden upright. Ancient Egypt. Each player has nine painted on the front. This is 1911.29.12. -

The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31 March 2012. HC 304 Session 2012-2013

THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009-476) Ordered By the House of Commons to be printed on 9th July 2012 HC 304 London: The Stationery Office £10.75 © The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.geffrye-museum.org.uk ISBN: 9780102977349 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2487680 07/12 21997 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST (Company Number 2476642) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR -

Central Oxford

Food & Drink Where to Stay Central Oxford dailyinfo.co.uk/venues/hotels D Going Out FARNDON R to Summertown, ring road (A34) to Summertown, ring road (M40) to Victoria Arms, Old Marston K Bath Place Hotel 4-5 Bath Place, Holywell St, OX1 3SU I6 D E F G H I & Marston Ferry Rd J L Historic, comfortable cottage-style rooms in the heart of Oxford. Simpkins Lee dailyinfo.co.uk/venues/restaurants Guest parking. 01865 791812 D Theatre RD AM R round W [email protected] www.bathplace.co.uk PTO for Summertown Map Y H s G alk Cinemas dailyinfo.co.uk/events/cinema OR ’ Cafe Loco The Old Palace, 85/87 St Aldate’s, OX1 1RA H9 UR N e RB e E B Arts venues Open all day, great setting. Find us opposite the Christ Church 24-26 George St, OX1 2AE T F b The Bocardo Hotel G6 R AN Rose & Crown Y n Curzon Cinema G8 e Meadow gates. Mon-Fri: 7.30am-6pm, Sat: 9am-6pm, Sun: 9.30am-6pm C A F Boutique hotel offering excellent accommodation in the heart of W z £ I Lady Margaret Hall New boutique cinema expected to open in Westgate Centre, autumn 2017. D E a Art Galleries 01865 200959 [email protected] B the city centre. 01865 591234 A European L L U M D Lazenbee’s www.goingloco.com RDKINGSTON R Studies dailyinfo.co.uk/events/exhibitions Odeon Cinemas (mainstream and blockbuster films) [email protected] www.thebocardo.co.uk N T O R BANBURY RD Pond L Centre B R Odeon, George St 0871 2244 007 G6 E (St Antony’s) D O D WOODSTOCK RD Oxford E Caffè Ethos off G10 Ethos Hotel and Caffè Ethos off G10 R H Cognitive & R Christ Church Picture Gallery Small charge I8 R T K Odeon, Magdalen St 0871 2244 007 G6 R R C see Ethos Hotel listing, under Where To Stay C O DE Violins Evolutionary O RI 59 and 60 Western Rd, Grandpont, OX1 4LF Latin N A D 300 paintings & 2000 drawings by Old Masters. -

The Art Fund in 2014/15

The Art Fund in 2014 /15 The Art Fund in 2014/15 Report of the Board of Trustees Chairman’s welcome p3 Mission and objectives p4 Art Acquisitions p10 Joint acquisitions and tours p18 Curators p23 Gifts, bequests and legacies p24 Public fundraising appeals p26 Sector Art Happens p33 Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year p34 Digital initiatives and new audiences p37 Community National Art Pass p41 Art Quarterly p43 Supporters p44 Resources Operations p51 Finance review p52 2 The Art Fund in 2014/15 3 Chairman’s welcome Ever since its foundation in 1903, the Art Fund has played a vital role in enhancing the health and quality of the UK’s museums and galleries, meeting the challenges of the hour whenever and wherever they have arisen. Budget cuts, the changing expectations of Since 2010, the Art Fund has supported We are doing all we can to help museums audiences, and the relentless development the curatorial profession by funding various attract, entertain and inform those who visit of new technologies are amongst the training and research opportunities. them. We believe in the power of art in problems – and opportunities – faced by In 2014 we gave £402,000, more than ever contemporary society and we are proud of the museum and arts sector today. We before, to this end – vitally important, in all we have done in its service in 2014, with have tried to help on all fronts: in 2014, our view, for the health and vitality of our the help of all of our supporters. alongside the grants for acquisitions that public art collections. -

ANNU AL REPO RT 2015 to 2016

University ofOxford University ANNUAL REPORT 2015 to 2016 Contents MISSION STATEMENT To inspire and share knowledge and understanding with global audiences about humanity’s many ways of knowing, being, creating and coping in our interconnected worlds by providing a world-leading museum for the cross-disciplinary study of humanity through material culture. 1 Director’s introduction 4 9 Running the Museum 27 Administration 27 2 The year’s highlights 6 Front of House 27 The VERVE project enters its last phase 6 Commercial activities 27 The Cook-Voyages Case 6 Donation boxes 27 Kintsugi: Celebrating Imperfection 6 Balfour Library 28 Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Public Engagement with Research 7 Buildings and maintenance 28 Cataloguing the handling collection 7 10 Appendices 29 3 Permanent galleries and temporary A Pitt Rivers Museum Board of Visitors as of exhibitions 8 1 August 2015 29 Permanent galleries 8 B Museum staff by section 29 Temporary displays 9 C Finance 30 Long Gallery 10 D Visitor numbers, enquiries, research visits and loans 31 Archive Case 10 Object collections 31 Photograph, manuscript, film and sound collections 31 4 Higher education teaching and research 12 Loans 31 Research Associates 14 E Interns, volunteers and work experience 32 Object collections 32 5 Collections and their care 16 Photograph, manuscript, film and sound collections 32 Photograph, manuscript, film and sound collections 16 Conservation department 32 Conservation work 18 Education department 32 Oxford University Internship Programme 18 F New acquisitions 33 Cover photograph: Japanese carver Hideta Kitazawa making Asante weights 18 Donations 33 Storage projects 18 Purchases 33 a Noh mask (2015.28.4), commissioned by the Museum for Catalogue databases 19 Transfers 33 its new Woodwork display as part of the VERVE project. -

Oxford Reminiscence Project (MOOR)

Renaissance South East: Case study Title of the project: The Museum of Oxford Reminiscence Project (MOOR) Institutes conducting the project: Oxford City Council, Oxford Museums Partnership (hosted by the Museum of Oxford in partnership with Oxford University Museums and the Oxfordshire County Council Museum Service). Funding: Renaissance South East Project dates: October 2009 – March 2011 (extended to February 2012) Project aims: For the museum and the partnership: Increase Oxford Museums Partnership’s community engagement capacity and deliver against Oxford City Council’s key priorities Make the Museum Service and collections, including museum objects and photographs, more accessible to members of the community in Oxford who would not usually consider using them either due to frailty or a belief that it has nothing of interest to them Expand the service delivered by Hands on Oxfordshire’s Heritage (HOOH) into Oxford City. For the older people: Encourage older people in the City of Oxford, predominantly in day- care and sheltered housing settings, to communicate with each other by sharing memories and stories in a fun way Help build a sense of community identity through social interaction and shared histories Help improve the use of memory and enhance the wellbeing of older people in Oxford Increase the participation in museum related activities amongst BME communities in Oxford Increase the sense of ownership of the heritage service to the wider Oxford community Target audience: Older people, especially non-traditional museum visitors 1 Project summary: In 2009, the Oxford Museums Partnership was set up to facilitate the planning and delivery of a reminiscence service, called the Museum of Oxford Reminiscence Project (MOOR), to groups of older people in the City of Oxford who were predominantly in day-care and sheltered housing settings. -

Executive Summary

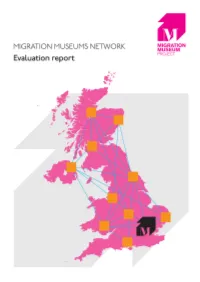

Executive summary This evaluation report reflects on a pilot year for a proposed Migration Museums Network that ran from November 2016 to November 2017. The Migration Museum Project (MMP) coordinated this pilot to gauge the demand and need for a Network to increase and improve work on migration and related themes across the museums, heritage and arts sectors (hereafter ‘heritage sector’) in the UK. The aims of the Network were to raise awareness of the growth of work on the important theme of migration, to share best practice and create opportunities for increased learning and collaboration. The pilot was supported by Arts Council England and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, and aligns with MMP’s aim of creating a permanent home for the Migration Museum in London, whilst learning from and supporting work on migration themes across the UK. The pilot was guided at all stages by a steering group that met regularly. At the outset it was agreed that the main goals of the pilot would be to: § Update existing scoping research conducted in 2009 by IPPR that mapped representation of migration themes across the heritage sector § Conduct a wide-reaching online survey to contribute to this research and gauge interest in the Network; and § Coordinate two events, in London and Newcastle, to bring people together to learn and network This report will describe the main activities of the pilot, analyse feedback, critically assess MMP’s learning, and conclude with proposed next steps. 2 + Contents 1 Network highlights 2 Network aims 3 Initial research and steering -

Join Us for a Cracking Night of Festive

YourOxford Winter 2011 Building a world-class city for everyone Circulation 62,000 ...and inside P2/3: Win concert tickets P13: New gift shop P7: A guide to the planning process JoinJoin usus forfor aa crackingcracking nightnight ofof festivefestive funfun Photo courtesy: Greg Smolonski, Photovibe COME and celebrate the arrival of local artists Cool ‘n’ Bodleian Library, Oxford Playhouse, the the Christmas season on Friday Groovy at the Ark T Museum of the History of Science, the Pitt Centre. Stage Rivers Museum and The Story Museum. 2 December with an exciting evening P10/11: Our performance of processions, lights, dance, art, live performances of Phil Kline’s Unsilent Night returns to Oxford music and performance in Oxford. dance and music for the second year. Oxford Contemporary and the light Music invite you to download his free PLUS Festivities start with a magical lantern switch-on will take place in St Giles, with sound sculpture of shimmering bells, P4: Visit our website procession, supported by MINI Plant presenters from BBC Radio Oxford keeping chimes and grand chorales and bring along Oxford, leaving the Old Fire Station in the crowds entertained as the evening unfolds. your portable stereo to join the promenade. P19: Your Councillors Gloucester Green at 6pm. St Giles will also host stalls selling hot food See our Light Night pull-out for full The 30-minute procession will weave and drinks, Christmas gifts and a special details of how to get involved. Recycle it... through the streets of Oxford, with Queen children’s area with rides and present-making Christmas Light Night in Oxford is Your Oxford is printed on Street, Cornmarket Street, and St Giles workshops.