Dancing with Physics Richard P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Junket, Vol. 6, No. 11

\ \ Title CiNTMS \ rage i Take It Jr Leave It 1 Juvenile Delinquency & Square Hancing 2 From The Mailbox 7 Coming Events at Folk 3ance House - - 11 Irish Dancing -.-_ 12 Bayanihan Dance Group >. 23 Polish State Folk Ballet 24 The P»und Party 25 Contra Dance - Maiden fteel ------ 27 Square Dance - Kitty Corner -------- 28 Folk Dance - Manitou Mixer — 29 Folk Song - If My fid T«p Were A Dancing Man 30 News 32 Book Review - Spiked Boots __- 34 It's Fun To Hunt 35 lasy To Make Decorations ---- — - 43 Holiday Foo4 46 The Town Criei; 5* ******* I :0^vM^... i< k *$ R L E..A. T'B I T The longer I stay in this "business the surer I am of two things to ensure its long life and continued in- terest in it: PROPER PROGRAMMING AMD A YOUTH PROGRAM . The callers who have been active for ten or more years and are still in demand are the ones who program each of their dances so that they give something for the "hot shot" dancer; something for the "newcomer" to square dancing; and a heck of lot for the people in between who outnumber the others maybe ten to one. The dances for the in-betweens will "be a good mixture of old and traditional dances and enough of the neweir ones to keep the floor on its toes. And one thing they never are guilty of: they never deliberately try to "throw the floor". Any idiot can do that; it takes a real good caller to sense the limitations of the group and arrange or re-arrange his material accordingly. -

Europeanfolkdanc006971mbp.Pdf

CZ 107911 EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE .-<:, t "* ,,-SS.fc' HUNGARIAN COSTUME most elaborate costume in Europe EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE ITS NATIONAL AND MUSICAL CHARACTERISTICS By JOAN LAWSON Published under the auspices of The Teachers Imperial Society of of Dancing Incorporated WITH ILLUSTKATIONS BY IRIS BROOKE PITMAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION NEW YORK TORONTO LONDON First published 1953 AHSOOrATKI) SIR ISAAC PITMAN & SONS. I/TT>. London Mblbourne Johannesburg SIR ISAAC PITMAN & SONS (CANADA), LTD. Toronto MADB IN QIUtAT DRTTACN AT TTIK riTMAN PRBSB^ BATH For DAME NZNETH DB VALOIS With Gratitude and Admiration Hoping it will answer in some part Iter a the request for classification of historical and musical foundation of National Dance Preface MrlHE famous Russian writer has said: and warlike Gogol "People living proud lives I that same in their a free life that express pride dances; people living show same unbounded will and of a diniate A poetic self-oblivion; people fiery express in their national dance that same and passion, languor jealousy," There is no such as a national folk dance that a dance thing is, performed solely within the boundaries as are known political they to-day. Folk dances, like all other folk arts, follow it would be to define ethnological boundaries; perhaps possible the limits of a nation from a of the dances the and the arts study people perform they practise. The African native of the Bantu tribe who asks the do great stranger "What you dance?" does so because he that the dance will knows, perhaps instinctively, stranger's him to understand of that man's life. -

Arizona Dance E-Star

Arizona Dance e-Star Arizona Dance e-Star a publication of the Arizona Dance Coalition Volume 2, Issue 10 November 2012 Dear Readers, November promises to be interesting with the elections and !anksgiving. We can only hope that the arts continue be a driving force in Arizona and that we have stronger support for the arts from our communities and elected o#cials. !is will be necessary in order to attract more grant monies from those who can give and believe the arts positively in$uence our economy (jobs), our intelligence (education) and our wellbeing (lifestyle). !e article on page 13 speaks to this topic and is written by Roberto Bedoya, Executive Director of the Tucson Pima Arts Council. November marks Bedoya's 6th year with TPAC. !e Member Spotlight shines on AZDance Group and Kenda Newbury (pg 12). Kenda's contribution to dance and working with children and adults with Table of Contents disabilities is signi"cant. !e Photo of the Month is of the Calendar of Events . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2-7 Terpsicore Dance Company—pronounced Terp%si% CORE— to bring attention to a dancer's "core." Master Classes & Workshops. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 !is November we can be thankful that there are so many Auditions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 events where we can celebrate DANCE. Project Dance ADC Member Announcements .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 Phoenix (pg 4) is one event where participants will actually Regional News . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10-11 discuss feeling blessed to dance. !e month begins with Photo of the Month . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .11 leftover Halloween/Vampires performances and ends with Member Spotlight: AZDance Group . .. .. .. .. .12 the beginnings of !e Nutcracker season! Inbetween we Article: Arts Boon or Drain?. -

The Arts, Grades 11 and 12

2010 REVISED The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11 and 12 The Arts CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Secondary Schools for the Twenty-First Century . 3 The Importance of the Arts Curriculum . 3 Ideas Underlying the Arts Curriculum . 5 Roles and Responsibilities in the Arts Program . 5 Attitudes in the Arts . 7 THE PROGRAM IN THE ARTS 9 Overview of the Program . 9 Curriculum Expectations . 13 Strands in the Arts Curriculum . 15 The Creative Process . 15 The Critical Analysis Process . 17 ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION OF STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT 23 Basic Considerations . 23 The Achievement Chart for the Arts: Grades 9–12 . 26 Information on the Achievement Chart . 28 SOME CONSIDERATIONS FOR PROGRAM PLANNING IN THE ARTS 31 Instructional Approaches . 31 Planning Arts Programs for Students With Special Education Needs . 32 Program Considerations for English Language Learners . 34 Environmental Education and the Arts . 37 Healthy Relationships and the Arts . 38 Equity and Inclusive Education in the Arts Program . 38 Multiple Literacies in the Arts . 40 Literacy, Mathematical Literacy, and Inquiry/Research Skills . 41 Critical Thinking and Critical Literacy in the Arts . 42 The Role of the School Library in the Arts Program . 43 The Role of Information and Communications Technology in the Arts Program . 44 The Ontario Skills Passport and Essential Skills . 45 Career Education . 45 Une publication équivalente est disponible en français sous le titre suivant : Le curriculum de l’Ontario, 11e et 12e année – Éducation artistique, 2010 This publication is available on the Ministry of Education’s website, at http://www.edu.gov.on.ca. Cooperative Education and Other Forms of Experiential Learning . 45 Planning Program Pathways and Programs Leading to a Specialist High Skills Major . -

Focus on Dance Education

FOCUS ON DANCE EDUCATION: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating, Performing, Responding, Connecting In Partnership with the International Guild of Musicians in Dance (IGMID) 17th Annual Conference October 7-11, 2015 Phoenix, Arizona CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS National Dance Education Organization Kirsten Harvey, MFA Editor Focus on Dance Education: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating Performing, Responding, Connecting Editorial Introduction In October 2015, the National Dance Education Organization met for their annual conference in Phoenix, Arizona to celebrate and honor the legacy, and individuality of the NDEO dance community. The warm spirit of Phoenix resonated with each educator and artist that came together at the beautiful Pointe Hilton Tapatio Cliffs Resort. Over 150 workshops, papers presentations, panels, master classes, social events, and performances were offered including full day pre-conference intensives that preceded the official start of the conference. The range of offerings for dance educators included a variety of experiences to foster inspiration, education, response, dialogue and connection to one another. Contributions to Focus on Dance Education: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating Performing, Responding, Connecting Conference Proceedings include paper presentations, panel discussions, workshops, and movement sessions presented from October 7-11, 2015. The proceedings include 4 abstracts, 9 full papers, 6 movement session summaries, 6 summary of workshop presentations, 2 panel discussion summaries, and 1 special interest group summary. One of the broadest ranges of submissions since I have been editing the proceedings. The NDEO top paper selection committee selected Caroline Clark’s paper titled “We Learned to Perform by Performing: Oral Histories of Ballet Dancers in a Beer Hall” for the Top Paper Citation. -

Participation in Ballroom Dancing: the Effects on the Social and Emotional Intelligence of Adolescents

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Master's Theses Student Research 12-1-2020 PARTICIPATION IN BALLROOM DANCING: THE EFFECTS ON THE SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE OF ADOLESCENTS ASHLEY BAXTER [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation BAXTER, ASHLEY, "PARTICIPATION IN BALLROOM DANCING: THE EFFECTS ON THE SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE OF ADOLESCENTS" (2020). Master's Theses. 178. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses/178 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2020 ASHLEY BAXTER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School PARTICIPATION IN BALLROOM DANCING: THE EFFECTS ON THE SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE OF ADOLESCENTS A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Ashley Baxter College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Theatre Arts and Dance Dance Education December 2020 This Thesis by: Ashley Baxter Entitled: Participation in Ballroom Dancing: The Effects on the Social and Emotional Intelligence of Adolescents has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Theatre and Dance, Program of Dance Education Accepted by the Thesis Committee: __________________________________________________ Sandra L. Minton, Ph.D., Chair, Advisor __________________________________________________ Christy O’Connell-Black, M.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School __________________________________________________ Jeri-Anne Lyons, Ph.D. -

Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into the Work of Mia Michaels

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into The Work of Mia Michaels Bethany Emery Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2534 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bethany Lynn Emery 2011 All Right Reserved Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into The Work of Mia Michaels A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Bethany Lynn Emery M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2011 M.A.R., Liberty Theological Seminary, 2003 BA, Alma College, 2001 Directors: Amy Hutton and Patti D’Beck, Assistant Professors, Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia July 2011 ii Acknowledgement The author would like to thank several people. I would like to thank my committee members Professor Amy Hutton, Dr. Noreen Barnes and Professor Patti D’Beck for sticking with me through this process and taking time during their summer plans to finish it out. I especially would like to thank Professor Hutton for her guiding hand, honest approach while also having an encouraging spirit. I would like to thank friends Sarah and Lowell for always being there for me though the happy and frustrating days. -

Conversations Dance Studies

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Decolonizing Dance Discourses Dance Studies Association 2020 | Volume XL CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Decolonizing Dance Discourses Dance Studies Association 2020 | Volume XL Table of Contents Preface | 2019 GATHERINGS Anurima Banerji and Royona Mitra: Guest Co-Editors ���������������������� 4 Introductory Remarks | OPENING WORDS Anurima Banerji and Royona Mitra ������������������������������������������������� 22 Takiyah Nur Amin������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 6 On Dance Black Women Respond to a Double Pandemic: Black Laws of Dance | "The Emotional W(ait)eight" | Jasmine Johnson����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Crystal U� Davis and Nyama McCarthy-Brown�������������������������������� 10 The Problem with "Dance" | The Politics of Naming the South Indian Dancer | Prarthana Purkayastha �������������������������������������������������������������������� 28 Nrithya Pillai������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 13 RUXIMIK QAK’U’X: Inextricable Relationalities It is Time for a Caste Reckoning in Indian in Mayan Performance Practice | "Classical" Dance | Maria Firmino-Castillo....................................................................... 31 Anusha Kedhar �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 On Choreography Discussing the Undiscussable, Part 2; Decentering Choreography: Natya as Postcolonial -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 228 SP 030 589 AUTHOR Beal, Rayma

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 228 SP 030 589 AUTHOR Beal, Rayma K., id.; Berryman-Miller, Sherrill, Ed TITLE Dance for the Ulder Adult. Focus on Dance XI. INSTITUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, Reston, VA. National Dance Association. REPORT NO ISBN-0-88314-385-2 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 176p.; Photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM AAHPERD Publications, P.O. Box 704, 44 Industrial Park Center, Waldorf, MD 20601 ($12.95 plus postage and handling). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) -- Guides General (050) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not AvailabLe from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Curriculum Development; *Dance; *Educational Resources; *Older Adults; Physical Fitness; *Program Development; Research ABSTRACT This monograph is a collection of articles designed to expand the information network, identify current programs, and provide research in the field of dance/movement and gerontology. Different approaches, techniques, and philosophies are documented by indi.fiduals who are active in the field. Articles are organized into six sections: (1) guidelines for activities with older adults; (2) programodelF; (3) research; (4) curricular program models; (5) intergenerational dance; and (6) resources. References accompany each article. The sixth section on selected reasons for dance and the older adult identifies: (1) books; (2) special publications; (3) selected articles from periodicals; (4) papers, monographs, proceedings and unpublished manuscripts; (5) masters and doctors degree theses; (6) films, videotapes, slides; (7) records, audiocassettes, manuals; (8) program and resource persons; (9) periodicals; and (10) agencies and organizations. (JD) *************mx*********x********************************vcx************ * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

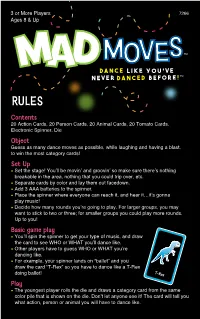

Contents Object Set up Basic Game Play Play

3 or More Players 7266 Ages 8 & Up TM TM RULES Contents 20 Action Cards, 20 Person Cards, 20 Animal Cards, 20 Tomato Cards, Electronic Spinner, Die Object Guess as many dance moves as possible, while laughing and having a blast, to win the most category cards! Set Up • Set the stage! You’ll be movin’ and groovin’ so make sure there’s nothing breakable in the area, nothing that you could trip over, etc. • Separate cards by color and lay them out facedown. • Add 3 AAA batteries to the spinner. • Place the spinner where everyone can reach it, and hear it…it’s gonna play music! • Decide how many rounds you’re going to play. For larger groups, you may want to stick to two or three; for smaller groups you could play more rounds. Up to you! Basic game play • You’ll spin the spinner to get your type of music, and draw the card to see WHO or WHAT you’ll dance like. • Other players have to guess WHO or WHAT you’re dancing like. • For example, your spinner lands on “ballet” and you draw the card “T-Rex” so you have to dance like a T-Rex doing ballet! T-Rex Play • The youngest player rolls the die and draws a category card from the same color pile that is shown on the die. Don’t let anyone see it! The card will tell you what action, person or animal you will have to dance like. • So, you’ll do something like maybe ballet dance like a T- Rex, or twist like a grandpa, etc. -

Dance 2011: Trip the Light Fantastic

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2010-2011 Season Productions 2001-2010 3-3-2011 Dance 2011: Trip the Light Fantastic Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2010-2011 Part of the Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "Dance 2011: Trip the Light Fantastic" (2011). 2010-2011 Season. 5. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2010-2011/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2001-2010 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010-2011 Season by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Otterbein University Department of Theatre & Dance I* ram Born Yesterday The Wild Party A Doll’s House Dance 2011: Trip the Light Fantastic The Storytelling Ability of a Boy OTTERBEI Jhe Drowsy Chaperone UNIVERSITY Otterbein University Department of Theatre and Dance Presents Dodcj^ 2011: Trip +h^ ]Jgh+ Fan+os+fe Artistic Director: Stella Hiatt Kane Choreographers: Kathy Bartelt Scott Brown Heather White-Cotterman Colleen Creghan Jon Devlin Maria Glimcher Stella Hiatt Kane Tammy Plaxico Sue Saurer Shayna Zalcberg Costume Designers: Ughting Designer: Rebecca White Dana White Berlyn Drabik Wilm Pierson Michelle Leibrock Jacob WP Ramey Sound Designer: Stage Manager: Eric Van Wagner Michael Minite March 3-6, 2011 Fritsche Theatre at Cowan Hall, 30 S. Grove St. Box Office: 614-823-1109 I !L...And, until we meet ag-ain..... Slainte’ » Choreographer: Stella Hiatt Kane Music: Gaelic Storm “The Buzzards of Bourbon Street,” “Raised on Black and Tans” bound Design, Bagpipes, and Bodhran Accompaniment: Josh Howey Lighting Design: Dana White Costume Design: Berlyn Drabik Set Design: Jacob WP Ramey Cast: Mikayla Agrella, Hayden Clifton, Lili Froehlich, Cameron Hobbs, Molly Sullivan, Simon Trumble Thts is dedicated to my two Irish Ijypes, Kip andEryn. -

Dance Standards Review and Revision Committee

2020 Colorado Academic Standards Page 1 Dance Standards Review and Revision Committee Chairperson Danielle Heller Lead Arts and Academic Faculty Immersion Schools Members Linda Marsh PreK-12 Teacher St. Mary's Academy Sandra Minton Co-Coordinator Dance Education MA Program, University of Northern Colorado Lisa Morgan Adjunct Faculty for Dance Colorado State University Katherine Reynolds-Sandstrom Director of Dance and Spanish Teacher Ballet Director at Dance Unlimited Russell Middle School, Colorado Springs School District 11 William Starn Dance Teacher Denver Public Schools Suzi Wilkins Movement Teacher The Da Vinci Academy, Academy District 20 Leslie Williams Dance Teacher Liberty High School, Academy District 20 2020 Colorado Academic Standards Page 2 State Board of Education and Colorado Department of Education Colorado State Board of Education CDE Standards and Instructional Support Office Angelika Schroeder (D, Chair) 2nd Congressional District Karol Gates Boulder Director Joyce Rankin (R, Vice Chair) Carla Aguilar, Ph.D. 3rd Congressional District Music Content Specialist Carbondale Ariana Antonio Steve Durham (R) Standards Project Manager 5th Congressional District Colorado Springs Joanna Bruno, Ph.D. Science Content Specialist Valentina (Val) Flores (D) 1st Congressional District Lourdes (Lulu) Buck Denver World Languages Content Specialist Jane Goff (D) Donna Goodwin, Ph.D. 7th Congressional District Visual Arts Content Specialist Arvada Stephanie Hartman, Ph.D. Rebecca McClellan (D) Social Studies Content Specialist 6th Congressional District Centennial Judi Hofmeister Dance Content Specialist Debora Scheffel (R) Drama and Theatre Arts Content Specialist 4th Congressional District Parker Jamie Hurley, Ph.D. Comprehensive Health Content Specialist Colorado Department of Education Physical Education Content Specialist Katy Anthes, Ph.D. Raymond Johnson Commissioner of Education Mathematics Content Specialist Secretary to the Board of Education Christine Liebe Melissa Colsman, Ph.D.