Teaching Students About Plagiarism: What It Looks Like and How It Is Measured

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

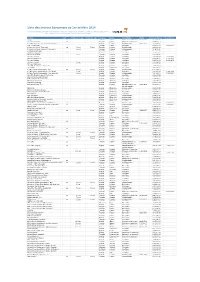

Liste Des Sources Europresse Au 1Er Octobre 2016

Liste des sources Europresse au 1er octobre 2016 Document confidentiel, liste sujette à changement, les embargos sont imposés par les éditeurs, le catalogue intégral est disponible en ligne : www.europresse.com puis "sources" et "nos sources en un clin d'œil" Source Pdf Embargo texte Embargo pdf Langue Pays Périodicité ISSN Début archives Fin archives 01 net oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 1276-519X 2005/01/10 01 net - Hors-série oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 2014/04/01 100 Mile House Free Press (South Cariboo) Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 0843-0403 2008/04/09 18h, Le (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/04 2014/02/18 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) oui 7 jours 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2013/04/09 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) (site web) 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2004/01/06 20 Minutes (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/30 24 Heures (Suisse) oui Français Suisse Quotidien 2005/07/07 24 heures Montréal 1 jour Français Canada Quotidien 2012/04/04 24 hours Calgary Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Edmonton Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Ottawa Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/02 2013/08/02 24 hours Toronto 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 hours Vancouver 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 x 7 News (Bahrain) (web site) Anglais Bahreïn Quotidien 2016/09/04 3BL Media Anglais États-Unis En continu 2013/08/23 40-Mile County Commentator, The oui 7 jours 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2001/09/04 40-Mile County Commentator, The (blogs) 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/05/08 2016/05/31 40-Mile County Commentator, The (web site) 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2011/03/02 2016/05/31 98.5 FM (Montréal, QC) (réf. -

Not for Immediate Release

Contact: Name Dan Gaydou Email [email protected] Phone 616-222-5818 DIGITAL NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY, MLIVE MEDIA GROUP ANNOUNCED TODAY New Company to Serve Communities Across Michigan with Innovative Digital and Print Media Products. Key Support Services to be provided by Advance Central Services Michigan. Grand Rapids, Michigan – Nov. 2, 2011 – Two new companies – MLive Media Group and Advance Central Services Michigan – will take over the operations of Booth Newspapers and MLive.com, it was announced today by Dan Gaydou, president of MLive Media Group. The Michigan-based entities, which will begin operating on February 2, 2012, will serve the changing news and information needs of communities across Michigan. MLive Media Group will be a digital-first media company that encompasses all content, sales and marketing operations for its digital and print properties in Michigan, including all current newspapers (The Grand Rapids Press, The Muskegon Chronicle, The Jackson Citizen Patriot, The Flint Journal, The Bay City Times, The Saginaw News, Kalamazoo Gazette, AnnArbor.com, Advance Weeklies) and the MLive.com and AnnArbor.com web sites. “The news and advertising landscape is changing fast, but we are well-positioned to use our talented team and our long record of journalistic excellence to create a dynamic, competitive, digitally oriented news operation,” Gaydou said. “We will be highly responsive to the changing needs of our audiences, and deliver effective options for our advertisers and business partners. We are excited about our future and confident this new company will allow us to provide superior news coverage to our readers – online, on their phone or tablet, and in print. -

Dying Languages: Last of the Siletz Speakers 1/14/08 12:09 PM

Newhouse News Service - Dying Languages: Last Of The Siletz Speakers 1/14/08 12:09 PM Monday January 14, 2008 Search the Newhouse site ABOUT NEWHOUSE | TOP STORIES | AROUND THE NATION | SPECIAL REPORTS | CORRESPONDENTS | PHOTOS Newhouse Newspapers Dying Languages: Last Of The Siletz Speakers Newhouse Spotlight The Ann Arbor News By NIKOLE HANNAH-JONES The Bay City Times c.2007 Newhouse News Service The Birmingham News SILETZ, Ore. — "Chabayu.'' Bud The Bridgeton News Lane presses his lips against the The Oregonian of Portland, Ore., is The Express-Times tiny ear of his blue-eyed the Pacific Northwest's largest daily grandbaby and whispers her newspaper. Its coverage emphasis is The Flint Journal Native name. local and regional, with significant The Gloucester County Times reporting teams dedicated to education, the environment, crime, The Grand Rapids Press "Ghaa-yalh,'' he beckons — business, sports and regional issues. "come here'' — in words so old, The Huntsville Times ears heard them millennia before The Jackson Citizen Patriot anyone with blue eyes walked Featured Correspondent this land. The Jersey Journal He hopes to teach her, with his Sam Ali, The Star-Ledger The Kalamazoo Gazette voice, this tongue that almost no one else understands. Bud Lane, the only instructor of Coast Athabaskan, hopes The Mississippi Press to teach the language to his 1-year-old granddaughter, Sam Ali, an award- Halli Chabayu Skauge. (Photo by Fredrick D. Joe) winning business The Muskegon Chronicle As the Confederated Tribes of writer, has spent The Oregonian Siletz Indians celebrate 30 years the past nine years since they won back tribal status from the federal government, the language of their at The Star-Ledger The Patriot-News people is dying. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

DETROIT-METRO REGION Detroit News Submit Your Letter At: Http

DETROIT-METRO REGION Press and Guide (Dearborn) Email your letter to: Detroit News [email protected] Submit your letter at: http://content- static.detroitnews.com/submissions/letters/s Livonia Observer ubmit.htm Email your letter to: liv- [email protected] Detroit Free Press Email your letter to: [email protected] Plymouth Observer Email your letter to: liv- Detroit Metro Times [email protected] Email your letter to: [email protected] The Telegram Newspaper (Ecorse) Gazette Email your letter to: Email your letter to: [email protected] [email protected] Belleville Area Independent The South End Submit your letter at: Email your letter to: [email protected] http://bellevilleareaindependent.com/contact -us/ Deadline Detroit Email your letter to: Oakland County: [email protected] Birmingham-Bloomfield Eagle, Farmington Wayne County: Press, Rochester Post, Troy Times, West Bloomfield Beacon Dearborn Heights Time Herald/Down River Email your letter to: Sunday Times [email protected] Submit your letter to: http://downriversundaytimes.com/letter-to- Royal Oak Review, Southfield Sun, the-editor/ Woodward Talk Email your letter to: [email protected] The News-Herald Email your letter to: Daily Tribune (Royal Oak) [email protected] Post your letter to this website: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQL Grosse Pointe Times SfyWhN9s445MdJGt2xv3yyaFv9JxbnzWfC Email your letter to: [email protected] OLv9tDeuu3Ipmgw/viewform?c=0&w=1 Grosse Pointe News Lake Orion Review Email your -

Advance Local | 4 Times Square |11Th Floor | New York, NY 10036 | 212.286.7872

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: ADVANCE LOCAL ANNOUNCES PAID SUMMER INTERNSHIP PROGRAM AT ITS LOCAL AFFILIATES Intern Positions in Content and Sales & Marketing at leading news brands New York, NY - January 14, 2014 – Advance Local, a leading media organization affiliated with 12 news and information websites and 30+ newspapers in communities throughout the U.S., announced the launch of a paid national internship program with positions in its local content and sales & marketing departments. The program is open to current, full-time undergraduate or graduate students pursuing a degree in Journalism, Business, Communications, or related fields. Positions are available at the following Advance Local group companies: • Alabama Media Group (AL.com, The Birmingham News, The Huntsville Times, Press-Register, The Mississippi Press) • MassLive.com • MLive Media Group (MLive.com, The Bay City Times, The Flint Journal, The Grand Rapids Press, Jackson Citizen Patriot, Kalamazoo Gazette, Muskegon Chronicle, The Saginaw News, The Ann Arbor News) • NJ.com • NOLA Media Group (NOLA.com and The Times-Picayune) • Northeast Ohio Media Group (which represents cleveland.com, The Plain Dealer and Sun News for sales and marketing and which also provides some content to the website and the newspapers) • Oregonian Media Group (OREGONLIVE.com, The Oregonian, Hillsboro Argus, Beaverton Leader and Forest Grove Leader) • PA Media Group (PennLive.com and The Patriot News) • Syracuse Media Group (syracuse.com and The Post-Standard) Participants will be immersed in one Advance Local market for 8 weeks and then come together for a national summit in the New York City area with fellow interns from across the country. Students must be available to work between June 2, 2014 and July 25, 2014. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

Foundation for Florida's Future, Key Reads: 10/26/11 NATIONAL

From: Clare Crowson ([email protected]) <[email protected]> To: Undisclosed recipients: CC: Date: Wed, 10/26/2011 9:40:46 AM Subject: Foundation for Florida’s Future, Key Reads: 10/26/11 Foundation for Florida’s Future, Key Reads: 10/26/11 For more education news, visit www.TheEdFly.com. NATIONAL NEWS 1) Governors Bush And Wise Announce Blueprint For Digital Education Initiative; Beuerman – Pelican Post 2) eLearning Update: Private Providers Need Public Oversight; Quillen – Education Week 3) Study finds flaws in virtual education, including motives of for-profit virtual schools; Rockwell – News Service of Florida 4) Study: States' Teacher Evaluation Policies Are a-Changin'; Heitin – Education Week STATE NEWS 5) School District Says No To Teacher Bonus Grant; Manning – National Public Radio 6) World-Class Schools for Iowa; Reading – KIMT TV 7) Opinion: Don't blame Illinois' education failures on NCLB; Journal-Courier – Staff 8) Michigan districts moving closer to a nationwide K-12 curriculum; Mack – Kalamazoo Gazette NATIONAL NEWS Governors Bush And Wise Announce Blueprint For Digital Education Initiative Pelican Post By: Jamison Beuerman October 25, 2011 http://www.thepelicanpost.org/2011/10/25/governors-bush-and-wise-announce-blueprint-for-digital-education-initiative/ ‘Roadmap for Reform’ contains detailed recommendations for state policymakers on digital learning This past week, former Florida Governor and chairman of Digital Learning Now! Jeb Bush and former West Virginia Governor Bob Wise unveiled an expansive plan for utilizing technology to achieve educational progress entitled the “Roadmap for Reform: Digital Learning.” The detailed 72-point plan aims to bridge the considerable gap between student needs and available state resources using technology and digital learning. -

Media Kit September 2019

MEDIA KIT SEPTEMBER 2019 95+ YEARS OF CLIENT STORYTELLING. SMARTER MARKETING. LOCAL PRESENCE. NATIONAL REACH. MLive Media Group www.mlivemediagroup.com [email protected] 800.878.1400 20190911 Table Of Contents ABOUT US ....................................................................................................3 NATIONAL REACH ............................................................................... 4 MARKETING STRATEGISTS ............................................................5 CAPABILITIES........................................................................................... 6 DIGITAL SOLUTIONS .......................................................................... 8 TECH STACK ............................................................................................. 9 MLIVE.COM .............................................................................................. 10 PRINT SOLUTIONS ...............................................................................11 PRINT ADVERTISING ........................................................................12 INSERT ADVERTISING ......................................................................13 NEWSPAPER DISTRIBUTION MAP ...................................... 14 MICHIGAN’S BEST ...............................................................................15 CLIENTS RECEIVE ................................................................................17 TESTIMONIALS .................................................................................... -

December 4, 2017 the Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washi

December 4, 2017 The Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Re: Uncoated Groundwood Paper from Canada, Inv. Nos. C–122–862 and A-122-861 Dear Secretary Ross: On behalf of the thousands of employees working at the more than 1,100 newspapers that we publish in cities and towns across the United States, we urge you to heavily scrutinize the antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed by North Pacific Paper Company (NORPAC) regarding uncoated groundwood paper from Canada, the paper used in newspaper production. We believe that these cases do not warrant the imposition of duties, which would have a very severe impact on our industry and many communities across the United States. NORPAC’s petitions are based on incorrect assessments of a changing market, and appear to be driven by the short-term investment strategies of the company’s hedge fund owners. The stated objectives of the petitions are flatly inconsistent with the views of the broader paper industry in the United States. The print newspaper industry has experienced an unprecedented decline for more than a decade as readers switch to digital media. Print subscriptions have declined more than 30 percent in the last ten years. Although newspapers have successfully increased digital readership, online advertising has proven to be much less lucrative than print advertising. As a result, newspapers have struggled to replace print revenue with online revenue, and print advertising continues to be the primary revenue source for local journalism. If Canadian imports of uncoated groundwood paper are subject to duties, prices in the whole newsprint market will be shocked and our supply chains will suffer. -

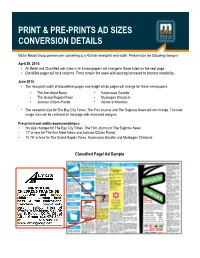

Print & Pre-Prints Ad Sizes

PRINT & PRE-PRINTS AD SIZES CONVERSION DETAILS MLive Media Group presses are converting to a 43 inch newsprint web width. Please note the following changes: April 29, 2014: • All Retail and Classified ads sizes in all 8 newspapers will change to those listed on the next page. • Classified pages will be 8 columns. Fonts remain the same with spacing increased to improve readability. June 2014: • The newsprint width of broadsheet pages and height of tab pages will change for these newspapers: • The Ann Arbor News • Kalamazoo Gazette • The Grand Rapids Press • Muskegon Chronicle • Jackson Citizen-Patriot • Advance Weeklies • The newsprint size for The Bay City Times, The Flint Journal and The Saginaw News will not change. The new image area will be centered on the page with increased margins. Pre-print insert width recommendations: • No size changes for The Bay City Times, The Flint Journal or The Saginaw News • 11” or less for The Ann Arbor News and Jackson Citizen Patriot • 10.75” or less for The Grand Rapids Press, Kalamazoo Gazette and Muskegon Chronicle Classified Page/ Ad Sample PRINT AD SIZES FOR 43 INCH PRESS SIZE Column x Inches = Image Area Retail Ad Sizes Full Junior Page Half H Half V Tower Quarter H Quarter V 6 column x 19.5" 5 column x 14.5" 6 column x 9.75" 3 Column x 19.5" 2 column x 19.5" 6 Column x 4.75" 3 column x 9.75" 117.00" 72.50" 58.50" 58.50" 39.00" 28.50" 29.25" Landscape Strip Eighth Small Portrait Business Card Mini Skybox 4 column x 4.75" 6 column x 2" 3 column x 4.75" 2 column x 4.75" 2 column x 2.5" 1 column -

Media Kit 2021

MEDIA KIT 2021 100+ YEARS OF CLIENT STORYTELLING. SMARTER MARKETING. LOCAL PRESENCE. NATIONAL REACH. MLive Media Group www.mlivemediagroup.com [email protected] 800.878.1400 20210401 Table Of Contents ABOUT US ....................................................................................................3 NATIONAL REACH ............................................................................... 4 MARKETING STRATEGISTS ............................................................5 CAPABILITIES........................................................................................... 6 DIGITAL SOLUTIONS .......................................................................... 8 TECH STACK ............................................................................................. 9 MLIVE.COM .............................................................................................. 10 PRINT SOLUTIONS ...............................................................................11 PRINT ADVERTISING.........................................................................12 INSERT ADVERTISING ......................................................................13 NEWSPAPER DISTRIBUTION MAP ...................................... 14 MICHIGAN’S BEST ...............................................................................15 CLIENTS RECEIVE ................................................................................17 TESTIMONIALS ..................................................................................... 18