Sketchbook 44 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-002686-Contents.Pdf (1.505Mb)

THE ilcttcrG of ~orate malpolt VOLUJIE I. HORACE WALPOLE, 'TO FRANCES COUNTESS OF WALDEGRAVE, THE RESTORER OF STRAWBERRY HILL, 'Ctbfs JEMtton of tbe :!Letters or HORACE WALPOLE IS WITH PERMISSION ll\SCRIBED BY HER OBLIGLD ANII OBEDIENT SERVANT, PETER CVNNL~GHAM. YO!,(. MR. CUNNINGHAM'S PREFACE. __..;... T:a:E leading features of this edition may be briefly stated :- I. The publication for the first time of the Entire Correspondence of Walpole (2665 Letters) in a chronological and uniform order. II. The reprinting greatly within the compass of nine volumes the fourteen, far £rom uniform, volumes, hitherto commonly known as the only edition of Walpole's Letters. III. The publication for the first time of 117 Letters written by Horace Walpole ; many in his best mood, all illustra tive of ·walpole's period; while others reveal matter of moment connected with the man himself. IV. The introduction for the fust time into any collection of Walpole's Letters, of 35 letters hitherto scattered over many printed books and papers. The letters hitherto unprinted are addressed to the following persons:- Duo OJ' GLOUOEBTER, ED!o!U!ID MALONE, MR. PELHA!o!. RoBERT DoDSLEY. M&. Fox (LoRD HoLLAND}. Is.uo REED. HoRACE WALPOLE, BEN, GROSVENOR BED!IORD. SIR EDWARD WALPOLE. CHARLES BEDFORD. LO.RD ORFORD. HENDERSO!I THE AcTOR. LoRD HARCOURT. EDMUND LODGE. LORD HERTFORD. DucHESS oF GLouoxsTER. LoRD Buoa.ur. LADY LYTTELTO!I. GEO.RGE MoNTAGO. LADY CEciLIA Joa:t<STON. Sis HoucE MANN, lUll. WDY BROWNII. FISH C.RA Wi'URI>. ETO. liTO, JOSEPH W ARTOJI, vi MR. CUNNINGHAM'S PREFACE. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

The Edinburgh Gazette 661

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE 661 At the Court at St. James', the 21st day of The Right Honourable Sir Francis Leveson June 1910. Bertie, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., G.C.V.O. PRESENT, The Right Honourable Sir William Hart Dyke, The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Bart. ; The Right Honourable Sir George Otto His Majesty in Council was this day pleased Trevelyan, Bart. ; to declare the Right Honourable William, Earl The Right Honourable Sir Charles Weutworth Beauchamp, K.C.M.G., Lord President of His Dilke, Bart., M.P. ; Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, and The Right Honourable Sir Edward Fry, His Lordship having taken the Oath of Office, G.C.B. ; took his place at the Board accordingly. The Right Honourable Sir John Hay Athole ALMBRIO FrazRor. Macdonald, K.C.B. ; The Right Honourable Sir John Eldon Gorst ; The Right Honourable Sir Charles John Pearson; At the Court at Saint James', the 21st day of The Right Honourable Sir Algernon Edward June 1910. West> G.C.B. j PRESENT, The Right Honourable Sir Fleetwood Isham The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Edwards, G.C.V.O., K.C.B., I.S.O. ; The Right Honourable Sir George Houstoun This day the following were sworn as Members Reid, K.C.M.G. ; of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, The Right Honourable William Kenrick ; and took their places at the Board accordingly:— The Right Honourable Sir Robert Romer, His Royal Highness The Duke of Connaught G.C.B. ; and Strathearn, K.G., K.T., K.P., G.C.B., The Right Honourable Sir Frederick George G.C.S.I., G.C.M.G., G.C.I.E., G.C.V.O.; Milner, Bart. -

Love Letters Between Lady Susan Hay and Lord James Ramsay 1835

LOVE LETTERS BETWEEN LADY SUSAN HAY AND LORD JAMES RAMSAY 1835 Edited by Elizabeth Olson with an introduction by Fran Woodrow in association with The John Gray Centre, Haddington I II Contents Acknowledgements iv Editing v Maps vi Family Trees viii Illustrations xvi Introduction xxx Letters 1 Appendix 102 Further Reading 103 III Acknowledgements he editor and the EERC are grateful to East Lothian Council Archives Tand Ludovic Broun-Lindsay for permission to reproduce copies of the correspondence. Thanks are due in particular to Fran Woodrow of the John Gray Centre not only for providing the editor with electronic copies of the original letters and generously supplying transcriptions she had previously made of some of them, but also for writing the introduction. IV Editing he letters have been presented in a standardised format. Headers provide Tthe name of the sender and of the recipient, and a number by which each letter can be identified. The salutations and valedictions have been reproduced as they appear in the originals, but the dates when the letters were sent have been standardised and placed immediately after the headers. Due to the time it took for letters from England to reach Scotland, Lord James Ramsay had already sent Lady Susan Hay three before she joined the correspondence. This time lapse, and the fact that thereafter they started writing to each other on a more or less daily basis, makes it impossible to arrange the letters sensibly in order of reply. They have instead been arranged chronologically, with the number of the reply (where it can be identified) added to the notes appended to each letter. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Kit-Cat Related Poetry

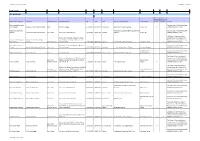

‘IN AND OUT’: AN ANALYSIS OF KIT-CAT CLUB MEMBERSHIP (Web Appendix to The Kit-Cat Club by Ophelia Field, 2008) There are four main primary sources with regard to the membership of the Kit-Cat Club – Abel Boyer’s 1722 list,1 John Oldmixon’s 1735 list,2 a Club subscription list dated 1702,3 and finally the portraits painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller between 1697 and 1721 (as well as the 1735 Faber engravings of these paintings). None of the sources agree. Indeed, only the membership of four men (Dr Garth, Lord Cornwallis, Spencer Compton and Abraham Stanyan) is confirmed by all four of these sources. John Macky, a Whig journalist and spy, was the first source for the statement that the Club could have no more than thirty-nine members at any one time,4 and Malone and Spence followed suit.5 It is highly unlikely that there were so many members at the Kit-Cat’s inception, however, and membership probably expanded with changes of venue, especially around 1702–3. By 1712–14, all surviving manuscript lists of toasted ladies total thirty-nine, suggesting that there was one lady toasted by each member and therefore that Macky was correct.6 The rough correlation between the dates of expulsions/deaths and the dates of new admissions (such as the expulsion of Prior followed by the admission of Steele in 1705) also supports the hypothesis that at some stage a cap was set on the size of the Club. Allowing that all members were not concurrent, most sources estimate between forty- six and fifty-five members during the Club’s total period of activity.7 There are forty- four Kit-Cat paintings, but Oldmixon, who got his information primarily from his friend Arthur Maynwaring, lists forty-six members. -

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 GB 345 National Gallery Archive NGA4 NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 5 boxes Harold Isherwood Kay Administrative history Harold Isherwood Kay was born on 19 November 1893, the son of Alfred Kay and Margaret Isherwood. He married Barbara Cox, daughter of Oswald Cox in 1927, there were no children. Kay fought in the First World War 1914-1919 and was a prisoner of war in Germany in 1918. He was employed by the National Gallery from 1919 until his death in 1938, holding the posts of Photographic Assistant from 1919-1921; Assistant from 1921-1934; and Keeper and Secretary from 1934-1938. Kay spent much of his time travelling around Britain and Europe looking at works of art held by museums, galleries, art dealers, and private individuals. Kay contributed to a variety of art magazines including The Burlington Magazine and The Connoisseur. Two of his most noted articles are 'John Sell Cotman's Letters from Normandy' in the Walpole Society Annual, 1926 and 1927, and 'A Survey of Spanish Painting' (Monograph) in The Burlington Magazine, 1927. From the late 1920s until his death in 1938 Kay was working on a book about the history of Spanish Painting which was to be published by The Medici Society. He completed a draft but the book was never published. HIK was a member of the Union and Burlington Fine Arts Clubs. He died on 10 August 1938 following an appendicitis operation, aged 44. Provenance and immediate source of acquisition The Harold Isherwood Kay papers were acquired by the National Gallery in 1991. -

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton Sir William Sydney, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick Soldier and knight and Duke of Northumberland; Earl of renown Marshal. “The minion of his time.” _________|_________ ___________|___ | | | | Lucy, marr. Sir Henry Sydney = Mary Sir Robt. Dudley, William Herbert Sir James three times Lord | the great Earl of 1st E. Pembroke Harrington Deputy of Ireland.| Leicester. Statesman and __________________________|____________ soldier. | | | | Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Robert, Mary = 2d Earl of Pembroke. Scholar, soldier, 1st Earl Leicester, Epitaph | courtier. Soldier & courtier. by Ben | | Johnson | | | Sir Robert, 2d Earl. 3d Earl Pembroke, “Learning, observation, Patron of letters. and veracity.” ____________|_____________________ | | | Philip Sydney, Algernon Sydney, Dorothy, 3d Earl, Patriot. Waller's one of Cromwell's Beheaded, 1683. “Saccharissa.” Council. First published in 1869. Second Edition, with an additional preface, 1892. Fifith corrected proof of the first electronic edition, 2019. Based on the text of the second edition. The page numbering and layout of the second edition have been preserved, as far as possible, to simplify cross-referencing. This is a corrected proof. This document forms part of the archive of Galton material available at http://galton.org. Original electronic conversion by Michal Kulczycki, based on a facsimile prepared by Gavan Tredoux. Many errata were detected by Diane L. Ritter. This edition was edited, cross-checked and reformatted by Gavan Tredoux. HEREDITARY GENIUS AN INQUIRY INTO ITS LAWS AND CONSEQUENCES BY FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., ETC. London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved CONTENTS PREFATORY CHAPTER TO THE EDITION OF 1892.__________ VII PREFACE ______________________________________________ V CONTENTS __________________________________________ VII ERRATA _____________________________________________ VIII INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. -

![The Saunderson Family of Little Addington [Microform] / Edited by W.D. Sweeting](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0515/the-saunderson-family-of-little-addington-microform-edited-by-w-d-sweeting-1340515.webp)

The Saunderson Family of Little Addington [Microform] / Edited by W.D. Sweeting

cs • Sis VA THE lamfrmum Hamilg *{pF |aITTLE Reprinted from Itorijjampionsjjir* Stoics # <$iums, Parts iv. and Ti., 1884-85. EDITED BY THE REV. W. D. SWEETING, M.A., VICAR OF MAXEY, MARKET DEEPING. faortfjamptont The Drtdbn Prbss: TAYLOR & SON, 9 Collsgb Street. 1887. of Little Addington. 'THIS ancient Northamptonshire family, seated for / over three centuries at Little Addington Mansion and at Moulton Manor House, disappeared from the county at the death of Thomas Saunderson, vicar of Little Addington, in 1855. It seems within the special province of "N.N.&Q." to put on record some account of a family so long settled within the county. The Northamptonshire branch is one of several ancient lines descended from Robert de Bedic, of Bedic, co. Durham, livingin the nth century, whose descendant in the sixth generation, Alexander de Bedjc, living in 1333, was the last to retain the territorial description, as his son was the first to use the patronymic^ by which the family has since been known, of Sanderson,, or Saunderson, i.e., son of Alexander. Itis a collateral branch of the Saundersons, viscounts Castleton, and of the family of the great bishop of Lincoln,Robert Saunderson :it has also, by later inter-marriages, been reconnected with both these lines. 4 The best— known branches of the family are five in number : (a) that of Hedleyhope, and Brancepeth, co. Durham j(b) that of Saxby, co. Lincoln j(c) that of Blyth and Serlby, co. Notts.; (d) that of Little Addington and Moulton, co. Northants ;and {c) thac of Coombe, co. Kent. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Manor Pub2003 for Pdf Print.Pub

Manor Farm Spaldwick A Background and Short History by Stuart Dixon September 2014 was an decisive time in the history of the Manor Farm house. Having been an important building on the High Street in Spaldwic since it was built in the 16th century it was rescued from decay and dilapidation for restoration. It had stood empty for many years since the last occupant died in 2005 and was in a sad and sorry state. To the delight of all the villagers it was bought by a professional restorer, Richard Johnson, whose enthusiasm for the pro(ect was matched inversely by those amateur diy-er*s who saw the amount of wor required, This short boo let attempts to put some history and colour on an important village landmar - there will be those who are more nowledgeable and I as for leniency where errors are found. .s usual I have probably rambled on and gone off at a tangent and there are still many gaps to be filled- consider this a first draft. Stuart Di0on January 2015 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Montagues 6 1opyhold Tenants 12 The 2arnards and 3ady Olivia Sparrow 13 The Ferrymans 16 INTRODUCTION The date of the building of the original Manor Farmhouse has yet to be determined e0actly. It was once thought to have been built about 1628 when the Earl, now Du e, of Manchester became 3ord of the Manor, but is probably older. In a 1826 Inventory of Huntingdon it is described as 9late 16th century: but recent e0amination of some of the timbers and structure show that it could be early 16th century. -

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and Deceased Masters of the British

I books N 5054 W78 1906oc Ropal flcademp of Arts EXHIBITION OF WORKS BY THE OLD MASTERS AND Rasters of tt)c Britts!) &rt)ool INCLUDING A COLLECTION OP WATER COLOUR DBA WINGS / ' ALSO A SELECTION OF DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES Br GEORGE FREDERICK WATTS, R.A, WINTER EXHIBITION THIRTY-SEVENTH YEAR MDCCCCYI WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED PRINTERS TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY THEGETTYCENTERLIBRARY y a / DU ITS, • LONDON AMSTERDAM EXHIBITION OF WORKS BY THE OLD MASTERS AND ®eceaseb jllasters of tl)c 2&rtttsl) School INCLUDING A COLLECTION OF WATER COLOUR DRAWINGS ALSO A SELECTION OF DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BT GEORGE FREDERICK WATTS, R.A. WINTER EXHIBITION THIRTY-SEVENTH YEAR A MDCCCCYI WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED PRINTERS TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY The Exhibition opens on Monday, January 1st, and closes on Saturday, March 10 th. Hours of Admission, from 9 A.M. to 6 p.m. Price of Admission, Is. Price of Catalogue, 6rZ. Season Ticket, 5s. General Index to the Catalogues of the first thirty Exhibitions, in three parts; Part I. 1870-1879, 2s.; Part II. 1880-1889 2s.; Part III. 1890-1899, Is. Gd. Xo sticks, umbrellas, or paiasols are allowed to be taken into the Galleries. They must be given up to the attendants at the Cloak rioom in the Entrance Hall. The other attendants are strictly forbidden to take charge of anything. The Refreshment Room is reached by the staircase leading out of the Water Colour Room. The Gibson (Sculpture) Gallery and the Diploma Galleries are open daily, from 11 A.M. to 4 p.m.