Brocklesby Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brocklesby Estate - Housing Application Form

BROCKLESBY ESTATE - HOUSING APPLICATION FORM Full Name Date of Birth Address Post Code Length of time at current address Telephone Number Home Work/Mobile) Email Address Marital Status: Single Married Separated Divorced Partner Spouse/Partner’s Date of Full Name Birth Children Ages How was your current property held by you? As private tenant As a lodger As owner As tenant of housing association Living with parents As a council tenant of which local authority ____________________ Employer’s/ Business Name & Address Position Spouse/Partner’s Current Employer’s/ Business Name & Address Position Reasons for applying for housing: Any connections to the Brocklesby Estate? Type of accommodation required Large House Cottage Bungalow Number of bedrooms required: 1 2 3 4 4+ Preferred location Great Limber Kirmington Brocklesby Cabourne Melton Ross Croxton Habrough Ulceby Croxby Swallow Wootton Any specific properties on the Estate? Maximum rental budget, per month, exclusive of Utilities and Council Tax? Will anyone else besides yourself pay towards the deposit? If yes, provide names and address of each person and amount contributing Length of Tenancy required? When ideally would you wish it to commence? Do you own any pets? Details of pets Number of cars? (and also e.g. caravans/boats, etc.) Size of garden preferred Do you or your spouse have any convictions? Have you ever been declared bankrupt? Have you any County Court Judgements against you? Have you ever been served a Notice Seeking Possession? Do you currently claim for any Government benefits? If yes please give details Are you currently in a rented property? How did you hear of the Brocklesby Estate? Any other information that may support your application: Referees – financial and personal (we will not contact these without your permission) Next of kin and their contact details I confirm that I am over 18 years of age and the information given above is true and accurate. -

The Edinburgh Gazette 661

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE 661 At the Court at St. James', the 21st day of The Right Honourable Sir Francis Leveson June 1910. Bertie, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., G.C.V.O. PRESENT, The Right Honourable Sir William Hart Dyke, The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Bart. ; The Right Honourable Sir George Otto His Majesty in Council was this day pleased Trevelyan, Bart. ; to declare the Right Honourable William, Earl The Right Honourable Sir Charles Weutworth Beauchamp, K.C.M.G., Lord President of His Dilke, Bart., M.P. ; Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, and The Right Honourable Sir Edward Fry, His Lordship having taken the Oath of Office, G.C.B. ; took his place at the Board accordingly. The Right Honourable Sir John Hay Athole ALMBRIO FrazRor. Macdonald, K.C.B. ; The Right Honourable Sir John Eldon Gorst ; The Right Honourable Sir Charles John Pearson; At the Court at Saint James', the 21st day of The Right Honourable Sir Algernon Edward June 1910. West> G.C.B. j PRESENT, The Right Honourable Sir Fleetwood Isham The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Edwards, G.C.V.O., K.C.B., I.S.O. ; The Right Honourable Sir George Houstoun This day the following were sworn as Members Reid, K.C.M.G. ; of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, The Right Honourable William Kenrick ; and took their places at the Board accordingly:— The Right Honourable Sir Robert Romer, His Royal Highness The Duke of Connaught G.C.B. ; and Strathearn, K.G., K.T., K.P., G.C.B., The Right Honourable Sir Frederick George G.C.S.I., G.C.M.G., G.C.I.E., G.C.V.O.; Milner, Bart. -

NCA Profile 42 Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes

National Character 42. Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 42. Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY's

648 PUB LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY's PUBLICANS continued. Carpenters' Arms, John Cawkwell, Fenton, Newark Blue Bell, Dixon Johnson, Scredington, Falkingham Carpenters' Arms, M. Redley, South st. Crowland, Peterbro' Blue Bell, Edwin Lacy, South Somercotes, Grimsby Carpenters' Arms, Saml. Thomlinson, West wood side,Bawtry Blue Bell, Joseph Mitchell, 14 North street, Grantham Carres Arms, Mrs. Susannah Elkington, Soutbgate, Sleaford Blue Bell, Edwin Newland, 378 Victoria st. nth. Gt.Gnmsby Castle, John Bull, Castle street, Stamford Blue Bell, William Pickwell, Pickworth, Falkingham Castle, Mrs. Sarah Corthorn, 55 Bailgate, Lincoln Blue Bell, George Smith, Whitecross st. Barton-on-Humber Castle inn, Joseph Denman, Torksey, Lincoln Blue Bell hotel, family, commercial & posting house, Robert Castle, Chapman Emerson, Kirton fen, Boston Ingram Swaby, Scunthorpe, Doncaster Castle inn, John George Hartley, Coningsby, Boston Blue Boar, Henry Elsom, Cow bit, Spalding Castle inn, James Hudson, Castle Bytham, Stamford Blue Boar, Robert Speight, 293 High street, Lincoln Castle, John Brown Pike, 46 South street, Horncastle Blue Boat, Thomas Heath,"\\ harf road, Grantham Castle inn, Samuel Reynolds, 36 J<'ydell street, Boston Blue Bull inn, John Brown, 64 Westgate, Grantham Castle, Samuel Strawson, Halltoft end, Freiston, Boston Blue Cow, Thomas Gray, 63 Castlegate, Grantham Cattle Market hotel, William Marshal!, Monks road, Lincoln Blue Cow, George Kelly Hudson, South Witham, Grantham Cavendish Arms, Hobert Wright, Tallin~:,rton, Stamford Blue Dog, William Cousins, Stainby, Grantham Chaplin Arms, Mrs. Mary Auckland, Martin, Lincoln Blue Dog, Geo. William Enderby, 10 Watergate, Grantham Chaplin's Arms, Mrs. Hannah Jobnson, Navenby S.O Blue Fox inn, Edward Holling-sworth, Gunby, Grantham Chaplin's Arms, Mrs. Fanny Nixon, Canwick road, Lincoln Blue Grey hound, HaywoodBrewster, Westborou£;"h,Grantham Chapman 's hotel, J spb. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 GB 345 National Gallery Archive NGA4 NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 5 boxes Harold Isherwood Kay Administrative history Harold Isherwood Kay was born on 19 November 1893, the son of Alfred Kay and Margaret Isherwood. He married Barbara Cox, daughter of Oswald Cox in 1927, there were no children. Kay fought in the First World War 1914-1919 and was a prisoner of war in Germany in 1918. He was employed by the National Gallery from 1919 until his death in 1938, holding the posts of Photographic Assistant from 1919-1921; Assistant from 1921-1934; and Keeper and Secretary from 1934-1938. Kay spent much of his time travelling around Britain and Europe looking at works of art held by museums, galleries, art dealers, and private individuals. Kay contributed to a variety of art magazines including The Burlington Magazine and The Connoisseur. Two of his most noted articles are 'John Sell Cotman's Letters from Normandy' in the Walpole Society Annual, 1926 and 1927, and 'A Survey of Spanish Painting' (Monograph) in The Burlington Magazine, 1927. From the late 1920s until his death in 1938 Kay was working on a book about the history of Spanish Painting which was to be published by The Medici Society. He completed a draft but the book was never published. HIK was a member of the Union and Burlington Fine Arts Clubs. He died on 10 August 1938 following an appendicitis operation, aged 44. Provenance and immediate source of acquisition The Harold Isherwood Kay papers were acquired by the National Gallery in 1991. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

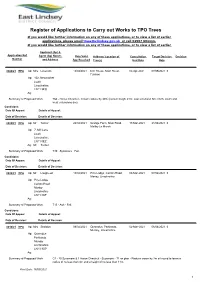

Register of Applications to Carry out Works to TPO Trees

Register of Applications to Carry out Works to TPO Trees If you would like further information on any of these applications, or to view a list of earlier applications, please email [email protected] or call 01507 601111. If you would like further information on any of these applications, or to view a list of earlier Applicant (Ap) & Application Ref Agent (Ag) Names Date Valid Address/ Location of Consultation Target Decision Decision Number and Address App Received Tree(s) End Date Date 0026/21 /TPA Ap: Mrs Laverack 12/03/2021 00:00:00Elm House, Main Street, 02-Apr-2021 07/05/2021 00:00:00 Fulstow Ap: 102, Newmarket Louth Lincolnshire LN11 9EQ Ag: Summary of Proposed Work T64 - Horse Chestnut - Crown reduce by 30% (current height 21m; east extension 5m; north, south and west extensions 6m). Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0023/21 /TPA Ap: Mr Turner 24/02/2021 00:00:00Grange Farm, Main Road, 17-Mar-2021 21/04/2021 00:00:00 Maltby Le Marsh Ap: 7, Mill Lane Louth Lincolnshire LN11 0EZ Ag: Mr Turner Summary of Proposed Work T39 - Sycamore - Fell. Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0022/21 /TPA Ap: Mr Lougheed 10/02/2021 00:00:00Pine Lodge, Carlton Road, 03-Mar-2021 07/04/2021 00:00:00 Manby, Lincolnshire Ap: Pine Lodge Carlton Road Manby Lincolnshire LN11 8UF Ag: Summary of Proposed Work T15 - Ash - Fell. Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0018/21 /TPA Ap: Mrs Sheldon 09/02/2021 00:00:00Quorndon, Parklands, 02-Mar-2021 06/04/2021 00:00:00 Mumby, Lincolnshire Ap: Quorndon Parklands Mumby Lincolnshire LN13 9SP Ag: Summary of Proposed Work G1 - 20 Sycamore & 1 Horse Chestnut - Sycamore - T1 on plan - Reduce crown by 2m all round to leave a radius of no less than 4m and a height of no less than 11m. -

Lincolnshire

5'18 FAR LINCOLNSHIRE. FARMERS continued. Brighton Edward, Leake, Boston Brown Andrew John, Garthorpe, Goole Boyfield Richard, Pointon, Falkingham Bringeman T.Scrane end,Freiston,Bostn Brown C. West Butterwick, Doncaster Boyfield T. West Pinchbeck, Spalding Bringeman Thomas, Langriville, Boston Brown C. High rd. Frampton, Boston BrackenburyG.&J.Salmonby,Homcastl Brinkley William, Kirton, Boston Brown Charles, Wyberton, Boston Brackenbury Mrs. Fanny, The Heath, Briswn Jonathan, Haven Bank, Wild- Brown Charles Henry, Howsham, Brigg Londonthorpe, Grantham more, Boston Brown Charles Thos. Anderby, Alford Brackenbury l. Claxby Pluckacre,Boswn Bristow C. Eaudyke, Quadring, Spalding Brown Edward, Sutton-on-Sea, Alford Brackenbury Jas. Harrington, Spilsby Bristow Mrs. E. North Kyme, Lincoln Brown Edward, Thurlby, Alford Brackenbury John, Bardney, Lincoln Bristow Frederick, Quadring, Spalding Brown F. West Butterwick, Doncaster Brackenbury J. Mareham-le-Fen,Boston Bristow George, Wildmore, Boston Brown George, Epworth, Doncaster Brackenbury Mrs. Mary, Hameringham, Bristow Jabez, Thornton-le-Fen, New Brown George, Ktrkby, Market Rasen Horncastle York, Boston Brown George, Maltby-le-"Marsh, Alford Brackenbury Thomas, Wilksby, Boston Bristow John George, Church end, Brown George, Usselby, Market Rasen Brackenbury Wm. Blyton, Gainsboro' Quadring, Spalding Brown Geo. West Butter wick, Doncaster :Brackenbury William, Carlby, Stamford Bristow Marshall, Horbling, Falkingham Brown Henry, Harmston, Lincoln Brackenbury William, Wilksby, Boston Bristow Thos. Dales, Billinghay, Lincoln Brown Hy. Sutton St. James, Wisbech Brackenbury William, Wytham, Bourn BristoweDavid,Lowgate,Wrangle,Boston Brown Jas. Hagnaby, Hannah, Alford Bradey Wm. & Jn. Lissington, Wragby Brittain B. Common, Moulton, Spalding Brown Jas. Fen, Heighington, Lincoln Bradley Mrs. C.(exors.of),Eagle,Newark Brittain Benj. Lindsey, Fleet, Holbeach Brown John, Black ~oor farm, Dod- Bradley Henry, Huttoft, Alford Brittain John (exors. -

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and Deceased Masters of the British

I books N 5054 W78 1906oc Ropal flcademp of Arts EXHIBITION OF WORKS BY THE OLD MASTERS AND Rasters of tt)c Britts!) &rt)ool INCLUDING A COLLECTION OP WATER COLOUR DBA WINGS / ' ALSO A SELECTION OF DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES Br GEORGE FREDERICK WATTS, R.A, WINTER EXHIBITION THIRTY-SEVENTH YEAR MDCCCCYI WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED PRINTERS TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY THEGETTYCENTERLIBRARY y a / DU ITS, • LONDON AMSTERDAM EXHIBITION OF WORKS BY THE OLD MASTERS AND ®eceaseb jllasters of tl)c 2&rtttsl) School INCLUDING A COLLECTION OF WATER COLOUR DRAWINGS ALSO A SELECTION OF DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BT GEORGE FREDERICK WATTS, R.A. WINTER EXHIBITION THIRTY-SEVENTH YEAR A MDCCCCYI WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED PRINTERS TO THE ROYAL ACADEMY The Exhibition opens on Monday, January 1st, and closes on Saturday, March 10 th. Hours of Admission, from 9 A.M. to 6 p.m. Price of Admission, Is. Price of Catalogue, 6rZ. Season Ticket, 5s. General Index to the Catalogues of the first thirty Exhibitions, in three parts; Part I. 1870-1879, 2s.; Part II. 1880-1889 2s.; Part III. 1890-1899, Is. Gd. Xo sticks, umbrellas, or paiasols are allowed to be taken into the Galleries. They must be given up to the attendants at the Cloak rioom in the Entrance Hall. The other attendants are strictly forbidden to take charge of anything. The Refreshment Room is reached by the staircase leading out of the Water Colour Room. The Gibson (Sculpture) Gallery and the Diploma Galleries are open daily, from 11 A.M. to 4 p.m. -

East Lindsey District Council Public Health Funerals Register

East Lindsey District Council Public Health Funerals Register Age at Next of Kin Traced Referred to Approx Value of Date and Cost of Surname Forename Initials Date & Place of Death Date & Place of Birth Usual Address Funeral Directors Details Death Y/N Treasury Solicitor Estate Funeral R Arnold Runeral Directors, 38 High 65 4th September 1946 15 Hammond Court, Mablethorpe No No Not Known 12th December 2012 Street Sutton on Sea LN12 2HB Elsden Nicholas N 29th November 2012 01507 442300 Cornwall (Isle of Scilly?) £1,225.00 15 Hammond Court, Mablethorpe R Arnold Runeral Directors, 38 High 56 12th April 1956 1A Breakwater Bungalow No No Not Known Nov-12 Street Sutton on Sea LN12 2HB Price David D T 8th November 2012 01507 442300 1A Breakwater Bungalow Not Known Sutton on Sea £1,450.00 Sutton on Sea Skegness And District Funeral 64 11th September 1948 9 Patten Avenue, Wainfleet Yes No Not Known 17th January 2013 Services 81 Roman Bank Skegness Brown Ivan I W 21st December 2012 PE25 2SW 01754 761758 Post Office Wainfleet All Saints Not Known £1,121 Skegness And District Funeral 54 15th December 1966 No Fixed Abode No No Nil 28th January 2013 Services 81 Roman Bank Skegness Griffiths William W J 25th December 2012 PE25 2SW 01754 761758 Skegness Seafront Not Known £950.00 Skegness And District Funeral 54 24th May 1958 Flat 2, 35 St Andrews Drive Yes No Not Known 28th January 2013 Services 81 Roman Bank Skegness Walker Graham G M 17th January 2013 PE25 2SW 01754 761758 35 St Andrews Drive, Skegness Skegness £990.00 Skegness And District Funeral -

The Landowner As Millionaire: the Finances of the Dukes of Devonshire, C

THE AGRICULTURAL HISTORY REVIEW ;i¸ SILVE1K JUBILEE P1KIZE ESSAY The Landowner as Millionaire: The Finances of the Dukes of Devonshire, c. I8OO-C. 1926 By DAVID CANNADINE HO were file wealthiest landowners In point of wealth, file House of Lords ex- between the Battle of Waterloo and hibits a standard whi& cannot be equalled in W tlle Battle of Britain? Many names any oilier country. Take the Dukes of were suggested by contemporaries. In I819 ille Northumberland, Devonshire, Sutherland American Ambassador recorded that the "four and Buccleuch, the Marquesses of West- greatest incomes in the kingdom" belonged to minster and Bute, the Earls of Derby, Lons- the Duke of Northumberland, Earl Grosvenor, dale, Dudley mad Leicester, mid Baron the Marquess of Stafford, and the Earl of Overstone, mid where (in the matter of Bridgewater, each of whom was reputed to wealth) will you find illeir equals collec- possess "one hmadred tllousand pounds, clear tively?8 of everything.''~ Forty ),ears later, H. A. Taine And early in the new century, T. H. S. Escott visited ille House of Lords where recorded tllese comments made by a friend on Tlle principal peers present were pointed out the Dukes of Northumberland and Cleveland: to me and named, with details of their These . are the persons who make the enormous fortunes: the largest amount to fortunes of the great privateWest End banks; £3oo,ooo a year. The Duke of Bedford has they take a pride in keeping a standing bal- £220,000 a year from land; the Duke of ance for which they never receive six pence; R.ichmond has 3oo,o00 acres in a single hold- but whose interest would make a hole in the ing.