Wired.2021.08.02 [Mon, 02 Aug 2021]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warned That Big, Messy AI Systems Would Generate Racist, Unfair Results

JULY/AUG 2021 | DON’T BE EVIL warned that big, messy AI systems would generate racist, unfair results. Google brought her in to prevent that fate. Then it forced her out. Can Big Tech handle criticism from within? BY TOM SIMONITE NEW ROUTES TO NEW CUSTOMERS E-COMMERCE AT THE SPEED OF NOW Business is changing and the United States Postal Service is changing with it. We’re offering e-commerce solutions from fast, reliable shipping to returns right from any address in America. Find out more at usps.com/newroutes. Scheduled delivery date and time depend on origin, destination and Post Office™ acceptance time. Some restrictions apply. For additional information, visit the Postage Calculator at http://postcalc.usps.com. For details on availability, visit usps.com/pickup. The Okta Identity Cloud. Protecting people everywhere. Modern identity. For one patient or one billion. © 2021 Okta, Inc. and its affiliates. All rights reserved. ELECTRIC WORD WIRED 29.07 I OFTEN FELT LIKE A SORT OF FACELESS, NAMELESS, NOT-EVEN- A-PERSON. LIKE THE GPS UNIT OR SOME- THING. → 38 ART / WINSTON STRUYE 0 0 3 FEATURES WIRED 29.07 “THIS IS AN EXTINCTION EVENT” In 2011, Chinese spies stole cybersecurity’s crown jewels. The full story can finally be told. by Andy Greenberg FATAL FLAW How researchers discovered a teensy, decades-old screwup that helped Covid kill. by Megan Molteni SPIN DOCTOR Mo Pinel’s bowling balls harnessed the power of physics—and changed the sport forever. by Brendan I. Koerner HAIL, MALCOLM Inside Roblox, players built a fascist Roman Empire. -

Recreation Fun, Concerts in Full Swing in Sturbridge

SPENCER FAMILY DENTAL Gentle Caring State of the Art Dentistry For The Whole Family Cosmetic Dentistry • Restorative Dentistry • Preventative Dentistry CROWNS • CAPS • BRIDGES • COMPLETE and PARTIAL DENTURES New We Strive NON SURGICAL GUM TREATMENT • ROOT CANAL THERAPY Patients SURGICAL SERVICES For Painless Welcome BREATH CLINIC-WE TREAT CHRONIC BAD BREATH Dentistry HERBAL DENTAL PRODUCTS • All Instruments Fully Sterilized • Most Insurances Accepted Dr. Nasser S. Hanna Conveniently Located On Route 9 • (Corner of Greenville St. & Main St.) 284 Main St., Spencer 508-885-5511 Mailed free to requesting homes in Sturbridge, Brimfield, Holland and Wales Vol. VII, No. 27 PROUD MEDIA SPONSOR OF RELAY FOR LIFE OF THE GREATER SOUTHBRIDGE AREA! COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY ONLINE: WWW.STURBRIDGEVILLAGER.NET Friday, July 11, 2014 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE Recreation fun, concerts “Be careful that victories do not in full swing in Sturbridge carry the seed of ARIOUS ACTIVITIES ON TURBRIDGE future defeats.” V S SUMMER SCHEDULE Ralph W. Sockman BY AMANDA COLLINS ers up the road, kids playing VILLAGER STAFF WRTIER catch while there are parents STURBRIDGE — If you drive sprawled out on a blanket as the past the Sturbridge town com- sun sets. mon on a Thursday night this Roll down the windows and INSIDE summer, you might see people take it slow to enjoy the sound of lugging lawn chairs and cool- live music from some the area’s ALMANAC ............. 2 most popular bands. Or better The Mad Bavarian Brass Band came yet, pull over and join in on the POLICE LOGS ......... 5 to play at the Sturbridge Town Sturbridge summertime tradi- OBITUARIES .......... -

Repowered Feminist Analysis of Parks and Recreation

Repowered Feminist Analysis of Parks and Recreation A Thesis submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication December 2018 By Bailee M. Bahr Southern Utah University Thesis Committee: Kevin Stein, PhD, Chair I certify that I have read and viewed this project and that, in my opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Professional Communication. Repowered Feminist Analysis 1 Kevin Stein __________________________________ Kevin Stein, Ph.D., Capstone Chair Matthew Barton __________________________________ Matthew Barton, Ph.D., MAPC Graduate Director Abstract Repowered Feminist Analysis 2 This paper analyzes the television show Parks and Recreation in order to find principles of Foss and Foss’ (2009) characteristics of repowered feminism. This paper aims to discover if Leslie Knope represents a new form of feminism, what characteristics specifically that she represents, and if these qualities contribute to a freer, less oppressed Leslie Knope. The analysis examines three episodes of the show and uses feminist rhetorical criticism to analyze the findings. I found that repowered feminism applies both to a feminist’s concerns with feminist issues and the applicability of repowered feminism to all types of problem solving. Knope, whether focusing directly on feminist issues or on the various obstacles she faces while doing her job, is usually presented as more successful when she implements the characteristics of repowered feminism. Keywords: parks and recreation, repowered feminism, pop culture Acknowledgements A massive hug and kiss to my adorable husband who encouraged me to finish my thesis in spite of the plethora of excuses. -

Exposing Safety Culture Neglect in Public Transit INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMALGAMATED TRANSIT UNION|AFL-CIO/CLC SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER 2017 Exposing safety culture neglect in public transit INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J. HANLEY International President JAVIER M. PEREZ, JR. International Executive Vice President NEWSBRIEFS OSCAR OWENS International Secretary-Treasurer INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS RICHARD M. MURPHY Newburyport, MA – [email protected] JANIS M. BORCHARDT Madison, WI – [email protected] PAUL BOWEN Canton, MI – [email protected] KENNETH R. KIRK Lancaster, TX – [email protected] MARCELLUS BARNES Flossmore, IL – [email protected] RAY RIVERA Lilburn, GA – [email protected] YVETTE TRUJILLO Thornton, CO – [email protected] GARY JOHNSON, SR. Cleveland, OH – [email protected] ROBIN WEST JIC Locals gather for collaborative training Halifax, NS – [email protected] More than 30 Locals from across the U.S. and Canada gathered at the Tommy Douglas Conference JOHN COSTA Center for an innovative Joint Industry Council training. The attendees heard from experts and staff Kenilworth, NJ – [email protected] on the new realities of bargaining and campaigning against large, deep-pocketed multinational CHUCK WATSON employers. The training included a comprehensive understanding of the RFP process, a breakdown Syracuse, NY – [email protected] of the revenue agreement, negotiations, strategies for building strength within our Locals, and CLAUDIA HUDSON Oakland, CA – [email protected] planning for organizing campaigns. The Locals also exchanged ideas and experiences in dealing with these companies that will change our strategic -

Shakespeare Comes to Town Page 14

Shakespeare comes to town Page 14 VOL. XX, NUMBER 22 • JUNE 21, 2019 WWW.PLEASANTONWEEKLY.COM WassermanWasserman reflectsreflects oonn ccareer,areer, criticalcritical timetime fforor ssportport iinn CCaliforniaalifornia PagePage 1212 5 NEWS Council backs downtown parking lot redesign 6 NEWS Alameda County Fair set for busy 2nd weekend 16 SPORTS Time to fix school sports funding system Premier Sponsors Amity Home Health Care Inc. Supporting Pleasanton Emergency Medical Group StStanfordanford HHealthealth CaCarere – VValleyCarealleyCy are Special thanks to our sponsors, underwriters and in-kind Eagle Sponsors Birdie Sponsors donors for making the 35th and Final Golf Tournament, American Hospice & Airflow Heating & Cooling, Inc. in honor of Larry Melim, a very special day. Home Health Care Heritage Bank of Commerce The event grossed over $186,000! Net proceeds will support Sensiba San Filippo LLP Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare’s Emergency Department. Pleasanton Nursing and Rehabilitation Center The CORE Group, Inc. Corporate Sponsors Tee Sponsors In-kind ACCO Engineered Systems Anderson Commercial Flooring Company Alameda County Fair Association Nottingham Cellars Callahan Property Co. Inc. CareOne Home Health Brad Kinney Productions Pleasanton Nursing & Rehabilitation Center Comtel Systems Technology From the Heart Senior Services Checkers Catering & Special Events Porky’s Pizza Palace CreekView Health Center Kindred at Home Christesen’s Western & English Saddlery Pump It Up Clementine’s/Country Waffles Retzlaff Vineyards Frank Bonetti Plumbing Monterey Private Wealth Concannon Vineyard Estate Royal Ambulance GetixHealth One Workplace Continuum Hospice & Palliative Care Sabio on Main J. Bray - D. Furtado The Parkview Assisted Living Dublin Ranch Golf Course Sacramento River Cats Law Offices of Stephenson Acquisto UNCLE Credit Union Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Sauced BBQ & Spirits and Plucked Chicken & Beer & Colman United Audit Systems, Inc. -

Western Upper Peninsula Citizens Advisory Council Division Reports

Western Upper Peninsula Citizen Advisory Council DNR Division Reports Date of Production: July 2021 (Information current as of 7/15/2021) This documentation is provided by Michigan DNR staff as a supplement for Western UPCAC Council members. Please email or call with any questions. Upper Peninsula Field Deputy Update – Stacy Haughey DNR Pocket Park – UP State Fair in Escanaba August 16 through August 22, 2021 The DNR Pocket Park is finally able to be open! This includes being open during the UP State fair, and oh my goodness, we have such a short time to plan! In less than a month (yikes!), the DNR Pocket Park will open to parents and children, both wanting to learn how to catch a fish or hit the bullseye with a bow or pellet gun. And we have something SUPER SPECIAL this year for the fair…..a Smokey Bear hot air balloon (more on that soon!). 2019 was THE most successful year yet, and all because of the overwhelming help from volunteers. Together, you all certainly make the park one of the top destinations to visit during the UP State Fair each year. We know this year may take on a little different meaning for some of you, and we very much understand. If, by chance, you are ready to get back into the swing of things, we surely hope we can count on you to volunteer this year! Please help us NOW by considering a few things below. 1. Look at your calendars and please consider volunteering that week (August 16-22). Your family member(s), friends, and coworkers (16 years and older) are also more than welcome to volunteer. -

Discover True Luxury with Cib Private

DISCOVER TRUE LUXURY WITH CIB PRIVATE CIB Private is your gateway to an exclusive world, tailored for you. Step into a world of privilege, that adds luxury and convenience to every facet of your life. Enjoy custom-tailored SUHPLXP EHQHðWV LQYHVWPHQW DQG OLIHVW\OH solutions to cater to your every need and to help you live every day to the fullest. To learn more, visit www.cibeg.com Enjoy safe and quick payments with AIB’s contactless cards Reliable Partner Customer Experience First-class CX Domain Expertise WE’RE NOT JUST A CONTACT CENTER RAYA’S GRAND TRANSFORMATION TOWARDS CX EXCELLENCE Throughout the journey of exerting every effort in establishing itself as a global '<PIEHIVXLIGSQTER]MWTVSYHXSƼREPP]ERRSYRGIMXWKVERHXVERWJSVQEXMSRJVSQ RAYA Contact Center (RCC) to RAYA Customer Experience (RCX). %WXLIGSQTER]ƼVWXWXEVXIHJSGYWMRKSRXLIQEMR 'YWXSQIV)\TIVMIRGIHMKMXEPTPEXJSVQW&YWMRIWWIW FYWMRIWWGETEFMPMXMIWXLEXLEZIEHMVIGXMQTEGXSRLS[ RS[GERFYMPHXLIMVGVSWWGLERRIPGYWXSQIVNSYVRI]W WYGGIWWJYPXLMWXVERWJSVQEXMSRGSYPHFIMXLEHEHIIT XSHVMZIFIXXIVFYWMRIWWSYXGSQIWERHFYMPHXVYWX[MXL YRHIVWXERHMRKSJXLIVIEWSRWJSVYRHIVKSMRKXLMWGLERKI XLIMVGYWXSQIVW7MRGI'YWXSQIV)\TIVMIRGI '< MWXLI *MVWXXSIRXIVRI[QEVOIXWERHWIXJSSXTVMRXWSRRI[ IQSXMSREPGSRRIGXMSREGYWXSQIVJIIPW[LIRIRKEKMRK KISKVETLMGEPPSGEXMSRWERHWIGSRHXSGSTI[MXLXLI [MXLEFYWMRIWW6%=%'<ƅWYPXMQEXIKSEPMWXSGVIEXI ZIVWEXMPMX]SJ&43WIVZMGIWƅGLERKIWERHI\TERHXLI HIPMKLXJYPI\TIVMIRGIWJSVMXWFYWMRIWWTEVXRIVW GSQTER]ƅWHMKMXEPGETEFMPMXMIWEGGSVHMRKP]8LIZIVWEXMPMX] SJXLI&43MRHYWXV]LEWWXVIRKXLIRIHMXWKPSFEPQEVOIX %LYKIFYWMRIWWXVERWJSVQEXMSREWWYGLLEWLEHER -

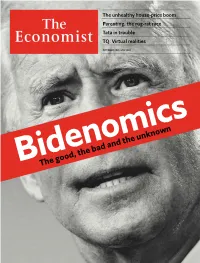

The Good, the Bad and the Unknown DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, Mcqs, Magazines

The unhealthy house-price boom Parenting, the rug-rat race Tata in trouble TQ: Virtual realities OCTOBER 3RD–9TH 2020 BidenomicsThe good, the bad and the unknown DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 WWW.NOKRIWALA.NET CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Is there the possibility of a better tomorrow?Will the investments I’ve made see me through? In aworld always shifting, can I be sure that my decisions willbe the correct ones? Or will these times remainthis unpredictable? For some of life’s questions, you’re not alone. Together we can find an answer. ubs.com/lifegoals As a firm providing wealth management services to clients, UBS Financial Services Inc. offers investment advisory services in its capacity as an SEC- registered investment adviser and brokerage services in its capacity as an SEC-registered broker-dealer. Investment advisory services and brokerage services are separate and distinct, differ in material ways and are governed by different laws and separate arrangements. It is important that clients understand the ways in which we conduct business, that they carefully read the agreements and disclosures that we provide to them about the products or services we offer. -

Agenda Book for the Executive Committee Meeting on July 19 & 20 (All Day Monday and Tuesday Until Noon)

TRB Executive Committee Meeting, July 19-20, 2021 Page 1 of 255 July 8, 2021 MEMORANDUM To: Members, TRB Executive Committee TAC Representatives to TRB Executive Committee From: Neil Pedersen Executive Director Subject: Agenda for TRB Executive Committee Meeting July 19 & 20, 2021 Enclosed or attached is the agenda book for the Executive Committee meeting on July 19 & 20 (all day Monday and Tuesday until noon). For those who will be attending in person, the meeting will be held in the Carriage House at the Woods Hole Study Center, Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Zoom invitations have been sent to those who will be participating online. All of you are receiving this information electronically. Chair Susan Shaheen urges all members to review the agenda material prior to the meeting so that time spent in oral briefings can be reduced to a minimum. This will also expedite the handling of the more routine items on the agenda, allowing more time for discussion of substantive transportation issues. At its spring meeting, the Subcommittee on Planning and Policy Review (SPPR) began work on developing a new TRB strategic plan that will be in alignment with the new National Research Council strategic plan. We will discuss the drafts key elements of the new TRB strategic plan. We will also start the process for developing the next edition of Critical Issues in Transportation. In addition to our traditional policy session on the afternoon of June 19th, which will be on racial equity issues in transportation, we will be having an one hour panel discussion with four USDOT senior leaders on the Biden Administration’s priorities related to transportation on Monday morning. -

Federal Register

FEDERAL REGISTER Vol. 86 Tuesday No. 108 June 8, 2021 Pages 30375–30532 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:33 Jun 07, 2021 Jkt 253001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\08JNWS.LOC 08JNWS jbell on DSKJLSW7X2PROD with FR_WS II Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 108 / Tuesday, June 8, 2021 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Regional Correspondence

From: Kilgore, Jason <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, August 2, 2021 1:04 PM To: Kilgore, Jason <[email protected]> Subject: [EXTERNAL] Peninsula Vaccinations as of Report Date August 2, 2021 Attached is a summary of the data as reported in VIIS as of this afternoon’s data upload. Note that the estimate is at 71.6% of the 12 and up population, up from 70.7% from last week’s estimate. Though not noted in the report, the combined Williamsburg and JCC vaccination rate is estimated to be 73.7%. ‐‐Jason Jason Kilgore Results Management and Analytics Riverside Health System 701 Town Center Drive Suite 1000 Newport News, VA 23606 CONFIDENTIALITY NOTICE: This e-mail message, including any attachments, is for the sole use of the intended recipient(s) and may contain confidential and privileged information. Any unauthorized review, use, disclosure or distribution is prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient, please contact the sender by reply e-mail and destroy all copies of the original message. Virginia Health Department COVID-19 First Dose Vaccination Summary Based on 12 years and older population VDH Update Date: 8/2/2021 VIIS Data By Locality Estimate from Federal Data* 242,606 419,294 57.9% 57,446 300,052 71.6% Total Peninsula First Dose Total Peninsula Population Total Peninsula % Est DOD+VAMC Total Peninsula+VAMC+DOD Peninsula+VAMC+DOD % 62,357 115,640 53.9% 19,200 81,557 70.5% Hampton First Dose Hampton Population Hampton % Hampton Fed 1st Dose Total Hampton Total Hampton % 47,802 67,654 70.7% 4,425 52,227 77.2% James -

Chicago's Election

EXPANDED SPORTS COVERAGE SUBSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE Questions? Call 1-800-Tribune Monday, April 1, 2019 Breaking news at chicagotribune.com FINAL PUSH FOR VOTES Preckwinkle and Lightfoot fan out across city ahead of historic mayoral election on Tuesday By Bill Ruthhart, Gregory There were no large-scale ral- nantly white, liberal lakefront, but from Montclare on the Northwest on the Northwest Side and has Pratt and Juan Perez Jr. lies or long-winded speeches from has since expanded her coalition Side, Lakeview on the North Side picked up backing from some Chicago Tribune the candidates ahead of Tuesday’s to include key endorsements from to South Chicago on the Southeast Latino aldermen but shown few historic runoff election that will more conservative neighborhoods Side, Roseland on the Far South signs of growing her support more Chicago mayoral candidates result in the city’s first African- along the Northwest and South- Side and Beverly on the Far broadly on the North Side. Lori Lightfoot and Toni Preck- American female mayor. Instead, west sides and among some top Southwest Side. As such, Preckwinkle spent winkle capped a final weekend of it mostly was an exercise in Latino leaders, including U.S. Rep. Preckwinkle, chair of the Cook almost her entire weekend en- campaigning by fanning out get-out-the-vote mobilization, Jesus “Chuy” Garcia. She’s also County Democratic Party, fin- couraging voters in the predomi- across the city to reach voters with the state of the race reflected been backed by businessman ished second in February thanks nantly black South and West sides everywhere from behind a bar in by where the candidates chose to Willie Wilson, who won the high- to a base centered on the South to head to the polls.