Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tyne Estuary Partnership Report FINAL3

Tyne Estuary Partnership Feasibility Study Date GWK, Hull and EA logos CONTENTS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 2 PART 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 6 Structure of the Report ...................................................................................................... 6 Background ....................................................................................................................... 7 Vision .............................................................................................................................. 11 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................................ 11 The Partnership ............................................................................................................... 13 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 14 PART 2: STRATEGIC CONTEXT ....................................................................................... 18 Understanding the River .................................................................................................. 18 Landscape Character ...................................................................................................... 19 Landscape History .......................................................................................................... -

Clara Vale Biennial Open Gardens with Art Fair, Pop up Choir, Live Music, Midsummer Supper and Bar

SUMMER 2019 NEWS Clara Vale biennial open gardens With art fair, pop up choir, live music, midsummer supper and bar Pay As You Feel on the day, with a suggested donation Sunday June 16th 2019 2-11pm of £5 per adult £2.50 per child. Please email Gardens and allotments open their [email protected] to register your place. gates from 2-5pm There’ll be afternoon tea and cakes served between 2-5pm. £3 entry with map Join us for a Midsummer Supper from 5pm into the evening. The Art Fair will be open in the main hall from 2pm featuring The pizza gang will fire up the oven and serve our very own the work of local artists including collographs, paintings, wood-fired pizzas. There’ll also be a delicious hog roast, ceramics, linocut, macramé, handpainted glass and silver jacket potatoes and mixed salads. jewellery. Whittonstall Community Band will be performing We’ll have a licensed bar throughout the afternoon and between 2-3pm in the hall yard evening. Payment by cash or cheque throughout the event. Come and be part of a one-off pop-up choir from 3-5pm, So please come along and have a wonderful time. led by highly experienced and well-loved musical director Beccy Owen. Whatever voice you have, and regardless of We’ll be sending out forms for opening your garden or experience, we guarantee that you’ll have a blast learning allotment shortly. a selection of uplifting songs in a safe, inclusive group Anyone wishing to volunteer and help on the day workshop, followed by a light-hearted performance in the (or before) please contact: beautiful, shaded Memorial Garden in the heart of Clara Vale. -

Northeast England – a History of Flash Flooding

Northeast England – A history of flash flooding Introduction The main outcome of this review is a description of the extent of flooding during the major flash floods that have occurred over the period from the mid seventeenth century mainly from intense rainfall (many major storms with high totals but prolonged rainfall or thaw of melting snow have been omitted). This is presented as a flood chronicle with a summary description of each event. Sources of Information Descriptive information is contained in newspaper reports, diaries and further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts and ecclesiastical records. The initial source for this study has been from Land of Singing Waters –Rivers and Great floods of Northumbria by the author of this chronology. This is supplemented by material from a card index set up during the research for Land of Singing Waters but which was not used in the book. The information in this book has in turn been taken from a variety of sources including newspaper accounts. A further search through newspaper records has been carried out using the British Newspaper Archive. This is a searchable archive with respect to key words where all occurrences of these words can be viewed. The search can be restricted by newspaper, by county, by region or for the whole of the UK. The search can also be restricted by decade, year and month. The full newspaper archive for northeast England has been searched year by year for occurrences of the words ‘flood’ and ‘thunder’. It was considered that occurrences of these words would identify any floods which might result from heavy rainfall. -

Subject Guide to Archival Holdings in North East England

SUBJECT GUIDE TO ARCHIVAL HOLDINGS IN NORTH EAST ENGLAND i INTRODUCTION This Subject Guide is based on the holdings of nine of the major archives in the North East of England: Alnwick Archives, Beamish Museum Archives, Gateshead Central Library, Newcastle City Library, the Great North Museum Library, The Literary & Philosophical Society, the Northumberland Archives, Newcastle University’s Robinson Library Special Collections, and Tyne & Wear Archives. Each of these have different rules of access and different opening times so ensure you have acquainted yourself with the details on the below websites. Alnwick Archives – http://www.alnwickcastle.com/explore/history/collections-and-archives Beamish Museum Archives – http://www.beamish.org.uk/archives/ Gateshead Central Library – http://www.gatesheadlibraries.com/ Newcastle City Library – http://library.newcastle.gov.uk/ Great North Museum Library – http://www.twmuseums.org.uk/great-north-museum.html The Literary & Philosophical Society – http://www.litandphil.org.uk/index Northumberland Archives – http://www.experiencewoodhorn.com/ Newcastle University’s Robinson Library – http://www.ncl.ac.uk/library/ Tyne & Wear Archives – http://www.twmuseums.org.uk/tyne-and-wear-archives.html Every effort has been made to cross-reference and direct users to other categories in which they might find other material relevant to their interests. Bear in mind that there is likely to be material that spans a number of categories (particularly, for example, general material relating to Newcastle upon Tyne and the North East), and checking all potentially relevant sections is advisable. This guide is indicative, rather than comprehensive, and the intention was to give details of significant items of interest. -

The Liberal and Labour Parties in North-East Politics 1900-14: the Struggle for Supremacy

A. W. PURDUE THE LIBERAL AND LABOUR PARTIES IN NORTH-EAST POLITICS 1900-14: THE STRUGGLE FOR SUPREMACY i The related developments of the rise of the Labour Party and the decline of the Liberal Party have been subjected to considerable scrutiny by his- torians of modern Britain. Their work has, however, had the effect of stimulating new controversies rather than of establishing a consensus view as to the reasons for this fundamental change in British political life. There are three main areas of controversy. The first concerns the char- acter of the Labour Party prior to 1918, the degree to which it was Socialist or even collectivist and could offer to the electorate policies and an image substantially different to those of the Liberal Party, and the degree to which it merely continued the Liberal-Labour tradition in alliance with, albeit outside the fold of, the Liberal Party. The second concerns the search for an historical turning-point at which Liberal decline and Labour's advance can be said to have become distinguishable. Perhaps the most vital debate centres around the third area of controversy, the nature of early- twentieth-century Liberalism and the degree to which a change towards a more collectivist and socially radical posture enabled it to contain the threat that the Labour Party presented to its electoral position. Research into the history of the Labour Party has modified considerably those earlier views of the movement's history which were largely formed by those who had, themselves, been concerned in the party's development. Few would now give such prominence to the role of the Fabian Society as did writers such as G. -

Before New Liberalism: the Continuity of Radical Dissent, 1867-1914

Before New Liberalism: The Continuity of Radical Dissent, 1867-1914 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Nicholas A. Loizou School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents: List of Figures 4 Abstract 6 Introduction 10 Research Objectives: A Revision in Politico-Religious History 10 A Historiographical Review 13 Methodology and Approach 23 1. Radical Dissent, Social Gospels and the Community, 1860-1906 28 1. Introduction 28 2. Growing Communitarianism and Religious Theology 29 3. The Importance of Radical Dissent and the Community 37 4. Nonconformity and the Urban Working Class 41 5. Nonconformity and the Liberal Party 51 6. Conclusion 56 2. Nonconformity, Liberalism and Labour 58 1. Introduction 58 2. The Significance of Nonconformity in Co-operative Class Relations 62 3. The Reform League 69 4. Nonconformity, Class and Christian Brotherhood in the Age of Gladstone 77 5. ‘That Church and King Mob’: Nonconformity, Brotherhood and Anti-Tory Rhetoric 82 6. Liberal-Labour Politics and the Late Nineteenth Century Social Turn in Nonconformity 87 7. Conclusion 93 3. Birmingham and the Civic Gospel: 1860-1886 94 1. Introduction 94 2. The Civic Gospel: The Origins of a Civic Theology 98 3. The Civic Gospel and the Cohesion of the Birmingham Corporation: 1860 – 1886 102 4. The Civic Gospel and Municipal Socialism: 1867-1886 111 5. The National Liberal Federation 116 6. The Radical Programme 122 7. Conclusion: The Legacy of Birmingham Progressivism 128 4. From Provincial Liberalism to National Politics: Nonconformist Movements 1860-1906 130 2 1. -

The National Politics and Politicians of Primitive Methodism: 1886-1922

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL The National Politics and Politicians of Primitive Methodism: 1886-1922. being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull By Melvin Johnson M.A. (Oxon), P.G.C.E., Diploma in Special Education (Visual Handicap). November 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations 4 Abstract 5 Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 8 Chapter One: The Politics of Primitive Methodism up to 1885. 29 1.1 Introduction 29 1.2 The increasing acceptance of political action 29 1.3 The main issues and political allegiances 33 1.4 A representative campaign of the 1870s and 1880s 41 Chapter Two: ‘As a people we are not blindly loyal’: 1886-1898 44 2.1 Introduction 44 2.2 The political allegiances and agendas of Primitive Methodism 46 2.2.1 The institutional response 46 2.2.2 The wider debate: the Connexional publications 48 2.2.3 The background, political allegiances and proclivities of Primitive Methodist MPs 54 2.3 Political issues 58 2.3.1 Labour and Capital 58 2.3.2 Temperance, gambling and smoking 66 2.3.3 Disestablishment and ecclesiastical matters 69 2.3.4 Education 71 2.3.5 Military matters 74 2.3.6 Ireland and other imperial matters 77 2.3.7 Land and landowners 81 2.3.8 Women’s suffrage and related issues 85 2.3.9 Other suffrage and constitutional issues 87 2.4 Heresy? 89 Chapter Three: ‘The social lot of the people must be improved’: 91 1899-1913 3.1 Introduction 91 3.2 The political allegiances and agendas of Primitive Methodism 93 3.2.1 The institutional response 93 3.2.2 The wider debate: the Connexional publications 97 3.2.3 The background, political allegiances and proclivities of Primitive Methodist MPs 103 3.3. -

Clara Vale-Thorp Academy-St Thomas More Catholic School Go North East S861 Effective From: 01/09/2020

Clara Vale-Thorp Academy-St Thomas More Catholic School Go North East S861 Effective from: 01/09/2020 Crawcrook, MainThorp Street Academy Ryton, Main RoadStella Road St Thomas More Catholic School Approx. 3 6 15 25 journey times Monday to Friday Clara Vale, Stannerford Road .... 0840 Crawcrook, Main Street 0805 0845 Thorp Academy 0808 0848 Ryton, Main Road 0811 .... Stella Road 0820 .... St Thomas More Catholic School 0830 .... Via: Main Street, Main Road, Stella Bank, Stella Road, Blaydon Bank, Wylam View, Heddon View, Back Lane, Croftdale Road St Thomas More Catholic School - Ryton - Clara Vale Go North East S861 Effective from: 01/09/2020 St Thomas MoreRyton, Catholic Main School RoadCrawcrook, Main ClaraStreet Vale, Stannerford Road Approx. 10 14 20 journey times Monday to Friday St Thomas More Catholic School 1555 Ryton, Main Road 1605 Crawcrook, Main Street 1609 Clara Vale, Stannerford Road 1615 Via: Croftdale Road, Blaydon Bank, Bridge Street, Stella Road, Main Road, Main Street, Crawcrook Lane, Stannerford Road, Stannerford, Clara Vale This information is provided by Nexus on behalf of Local Authorities, and is updated as and when changes occur. Nexus can accept no liability for any errors or omissions herein Barlow - Winlaton - Parkhead Estate - Ryton - Thorp Academy S863 Effective from: 01/09/2020 Gateshead Central Taxis Barlow, Barlow RoadWinlaton Bus StationParkhead Estate, ParkHeddon Lane View Stella Road Ryton, Main RoadThorp Academy Approx. 5 10 14 25 30 35 journey times Monday to Friday Barlow, Barlow Road 0740 Winlaton -

Newcastle International Airport Masterplan 2035 Consultation Report 2019 Masterplan 2035

Masterplan 2035 Newcastle International Airport Masterplan 2035 Consultation Report 2019 Masterplan 2035 Newcastle Airport Masterplan 2035 - Consultation Report Executive Summary Consultation on Newcastle International Airport’s (“the Airport”) Masterplan 2035 was undertaken from 10th May – 13th September 2018. It included a range of publicity events, public meetings and drop-ins, and direct engagement with key stakeholders. Feedback was received at these events, via an online survey, and written representations. Consultation The Masterplan consultation was published via written and digital news articles, social media, an email bulletin and community posters. The Masterplan press release was covered in 15 articles throughout the consultation period, as well as 4 community newsletters. The email bulletin reached 697 individual email addresses including all major regional stakeholders and all parish and local councillors within the North East LEP area. There were 46 Masterplan related posts on the Airport’s 4 social media platforms. On average social media posts about the Masterplan were seen by 5,103 people and of these 403 people actively engaged with the post. Direct engagement with local communities was undertaken through 4 public meetings and 11 drop-in events. A total of 242 people attended events, and average attendances were highest at public meetings. In addition 20 direct meetings were held with key regional stakeholders including transport providers, local authorities and local politicians. The form of these meetings ranged from telephone conversations to presentations and discussion sessions. Events Feedback In general support was expressed at the public consultation events for growth of the Airport and the Masterplan to deliver it. The benefits of a wider network of routes operating from the Airport were recognised, both for the economic betterment of the region and more individual choice for leisure travel. -

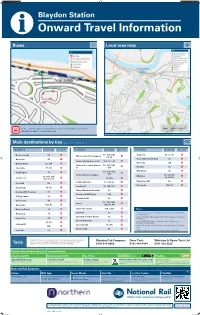

Blaydon Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Blaydon Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map In the event of engineering work, the bus or coach will collect from outside the station on the slip road Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at October 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 69 C 10, 10A, 10B, Swalwell 49, 69, 90 C Beacon Lough Metrocentre Interchange ^ C 49, 90 Bensham 49 C Team Valley North End 69 C Newcastle Business Park 10X, 12, 12A D B Bleach Green 12, 12A A The Folly 10A Newcastle Central Station 10, 10A, 10B, C Wardley 69 C Clara Vale R1, R4 B ^ 10X 10, 10A, 10B, Whickham 69 C Corbridge ^ 10 B C Newcastle Eldon Square 10X 12, 12A, 49, 10, 10A, 10B, Winlaton A Crawcrook B 69, 90, R3 10X, R1, R4 12, 12A D Parkhead Estate 12, 12A, 69 A Winlanton Mill R3 A Crookhill R4 B Woodside 10A, R1 B Prudhoe ^ 10, 10B, 10X B Dunston ^ 49, 90 C Queen Elizabeth Hospital 69 C Dunston Hill Hospital 69 C Rockwood Hill Estate 10A B Felling Square 69 C Rowlands Gill R3 A Gateshead 49 C 10, 10A, 10B, Ryton B Greenside 10A, R1 B 10X, R1, R4 Hanover Estate 12 A Ryton Woodside 10A, TB15 B Notes C For bus times and days of operation please see bus stop timetables 10 B Saltwell 69 Hexham ^ or contact Nexus Sheryburn Tower Estate R3 A Services 10, 10A, 10B, 12, 12A, 49, 69, R3 & R4 operate on Mondays Leam Lane 69 C to Sundays Snook Hill Estate 12 A Services 10X & 90 operate a limited peak time frequency on 69, 90 C Mondays to Fridays only Lobley Hill Stocksfield ^ 10, 10X B 69B A Service R1 operates a limited frequency on Mondays to Saturdays only. -

Overture: Guilty Men

Notes Overture: Guilty Men 1. ‘Cato’, Guilty Men (London, 1940); Kenneth O. Morgan, Michael Foot: A Life (London, 2007) pp. 72–82. 2. ‘Cato’, Guilty Men, pp. 17–21 for political scene setting; pp. 32–4 for Bevin and Lansbury. 3. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume 1, The Gathering Storm (London, 1948); C.L. Mowat, Britain Between the Wars, 1918–1940 (London, 1955) p. 142. The contingency of the Guilty Men myth’s appeal is analysed in Philip Williamson, ‘Baldwin’s Reputation: Politics and History 1937–1967’ Historical Journal 47:1 (2004) 127–168. 4. See the profile in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (hereafter ODNB) online http://www.oxforddnb.com/index/56/101056984/ (accessed 8 June 2014). 5. HC Deb 5th Series Volume 290 Columns 1930, 1932, 14 June 1934. 6. Mowat, Britain Between the Wars, p. 361; A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914–1945 (Oxford, 1965), p. 285. Mosley’s own contribution can be found in My Life (London, 1968). 7. Robert Skidelsky, Politicians and the Slump: the Labour Government of 1929–31 (London, 1967); Oswald Mosley (London, 1975). The latter includes the ‘lost leader’ comment at p. 13. 8. Peter Clarke, Lancashire and the New Liberalism (Cambridge, 1971). 9. Ross McKibbin, Parties and People: England 1914–1951 (Oxford, 2010); Duncan Tanner, ‘Class Voting and Radical Politics: the Liberal and Labour Parties 1910–1931’, in Miles Taylor and Jon Lawrence (eds.), Party State and Society: Electoral Behaviour in Britain since 1820 (Aldershot, 1997), pp. 106–30. 10. Oswald Ernald Mosley was born 19 November 1896 and succeeded to the baronetcy on 21 September 1928. -

TUC Report of Congress 2014 370.46 KB

Report of Congress 2014 The 146th Annual Trades Union Congress 7–10 September 2014, Liverpool 1 Contents General Council members 2014–2015 ...................................................................... 3 Section 1: Congress decisions ........................................................................................ 4 Part 1: Resolutions carried ............................................................................................................................ 5 Part 2: Motions lost ..................................................................................................................................... 39 Part 3: General Council statements ............................................................................................................ 40 Section 2: Keynote Speeches ....................................................................................... 43 Frances O’Grady ............................................................................................................................................ 44 Mohammad Taj ............................................................................................................................................ 48 Mark Carney ................................................................................................................................................. 50 Chuka Umunna MP ...................................................................................................................................... 55 Section 3: Unions