Invasive Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

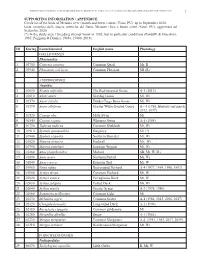

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

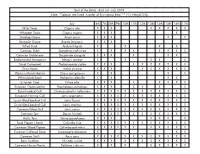

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I Hope You Have Fun Playing Birdwatching Bingo with Your Family

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I hope you have fun playing Birdwatching Bingo with your family. You can even share it with friends and do it over social media. To help you on your adventure, here is an identification sheet with all the different birds listed on your bingo card. With the help of this sheet and some binoculars, you will be on your way to becoming a fantastic birdwatcher. Most of these birds you can see visiting a birdfeeder, but some you might have to go on a walk and look for with a parent. To play, download and print the bingo cards for each player. Using pennies, pieces of paper, or even a pencil, mark the card when you see and identify the different birds. Don’t be frustrated if you don’t finish the game in one sitting, this game might be completed over a couple days. A great tool to help with IDing birds is the app MERLIN. This is a free bird ID app for your phone from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The website, www.allaboutbirds.org, is a great source too. Blue Jay - Scientific Name: Cyanocitta cristata - Identifiable Markings: o Blue above, light grey below. Black and white markings on wings and tail. Larger than a robin, smaller than a crow. Crest and long tail. - Photo: Females/Males Look Similar Brown-headed Cowbird - Scientific Name: Molothrus ater - Identifiable Markings: o Stout bill. Short tail and stocky body. Males are glossy black with chocolate brown head. Females are grey-brown overall, without bold streaks, but slightly paler throat. -

Are European Starlings Breeding in the Azores Archipelago Genetically Distinct from Birds Breeding in Mainland Europe? Verónica C

Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable To cite this version: Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable. Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (1), pp.95-100. 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x. hal-00535248 HAL Id: hal-00535248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535248 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:95–100 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x SHORT COMMUNICATION Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves & Kate Griffiths & Fiona R. Savory & Robert W. Furness & Barbara K. Mable Received: 6 May 2009 /Revised: 5 August 2009 /Accepted: 11 August 2009 /Published online: 29 August 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) has Keywords Azores . -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Science for Saving Species Research Findings Factsheet Project 4.2

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 4.2 Assessing the impacts of invasive species: Hollow-nesting birds in Tasmania In brief Background Predicting the impacts of invasive Invasive alien birds are found explore the known and theoretical species is difficult at large spatial across many areas of Australia. interaction network between the scales. This is because the interactions Many of these introduced birds cavity breeding birds in Tasmania, between invasive species and native use cavities, an important breeding and to identify which native species species vary across different species, resource for cavity nesting species. are likely impacted by the addition between different locations, over In Tasmania alone there are 27 of non-native species. time and in relation to other pressures species of hollow-nesting birds, We discovered that, overall, such as habitat loss, extensive fires, including three threatened species native hollow-nesting species climatic events and drought. and seven invasive hollow-nesting are likely facing increased levels bird species. The logging of big old Given that conservation and of competition for nesting sites trees with cavities and the addition management work is almost always as a result of non-native species of invasive species has likely led conducted under limited budgets and introductions. Such competition to increased competition over time, being able to quantify where is likely to decrease breeding the limited resource. However, and when invasive species are having opportunities for native species, the impact of most of these a significant impact on local species including some of Tasmania’s invasive species has not been is vital for effectively managing and threatened and endemic species. -

On the Preservation of the Beak in Confuciusornis (Aves: Pygostylia)

diversity Article On the Preservation of the Beak in Confuciusornis (Aves: Pygostylia) Amanda Falk 1, Jingmai O’Connor 2,3,* , Min Wang 2,3 and Zhonghe Zhou 2,3,* 1 Biology Department, Centre College, 600 W. Walnut St. Danville, KY 40422, USA; [email protected] 2 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing 100044, China; [email protected] 3 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Beijing 10010, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.O.); [email protected] (Z.Z.) Received: 27 October 2019; Accepted: 10 November 2019; Published: 11 November 2019 Abstract: The Confuciusornithiformes represent the most stem-ward avian occurrence of an edentulous rostrum. Although a keratinous beak is widely considered to have covered the rostrum in confuciusornithiforms, this feature is almost never preserved, having been previously reported only in the holotype of Confuciusornis dui and the holotype of Eoconfuciusornis zhengi. This strongly contrasts with the widespread preservation of the keratinous sheaths that cover the manual and pedal ungual phalanges. Here, we report on a third occurrence of a preserved rhamphotheca in a specimen of Confuciusornis sanctus. We illuminated the preserved traces using laser-stimulated fluorescence. Similarly to E. zhengi, the rhamphotheca has been preserved only as a two-dimensional trace, whereas ungual sheaths are preserved in three dimensions. In contrast to the traces preserved in C. dui, the rhamphotheca in the discussed specimen of C. sanctus is straight rather than upturned. This hints towards hidden morphological diversity within the thousands of Confuciusornis specimens, in which species may be further differentiated by soft tissue features or behaviors, much like many living birds, that cannot be detected in fossils, even with exceptional preservation. -

416 Common Starling Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 416 Common Starling Put your logo here Common Starling. Spring. Adult. Male (23-V). COMMON STARLING (Sturnus vulga- ris ) IDENTIFICATION Common Starling. 20-22 cm. Black plumage, with purple, green Spring. Adult. Pattern of and blue gloss in breeding plumage; strongly wing, breast and upper- spotted pale in winter; yellow bill in breeders, parts. dark in winter; short tail. Wing formula : the 9th primary is the longest (sometimes 8th and 9th similar). Juveniles are grey brown; pale superci- lium poorly pronounced; cheek mottled dark. 9ª 8ª 9ª 8ª 7ª 7ª Common Starling. Juvenile. Wing formula and head pattern. Common Starling. Win- ter. Wing formula and pattern of breast and upperparts. http://blascozumeta.com Write your website here Page 1 Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 416 Common Starling Put your logo here SIMILAR SPECIES Recalls that of a male Blackbird which has lon- ger tail and lacks glossy plumage or white spots. Spotless Starling is very similar but lacks green and purple gloss in breeding plumage and wing feathers lacks buff edges. Juvenile of Spotless Starling is almost indistinguishable by plumage but with pale supercilium quite pro- nounced and cheek poorly mottled dark; wing formula is different being the 8th primary the Spotless Starling. 9ª Blackbird. Male 8 7 Spotless Starling. Winter. Spotless Starling. Juvenile.Wing formula and head pattern. 9ª 8ª SEXING In breeding season, base of the lower mandible is 7ª grey-blue in males and white-pinkish in females . -

Common Urban Birds

Common Urban Birds Crested Pigeon Spotted Turtle Dove* Feral Pigeon* Noisy Miner New Holland Eastern Spinebill White-plumed Honeyeater Honeyeater JS SW SW SW SW JS JS (Crest on head) (White spots on neck) (Dark grey feathers usually with a (Black head, yellow around eyes) (Black and yellow wings, Black and (Black, white and reddish-brown (White lines on neck) shiny green neck) white striped chest) feathers) Nectarivore & Granivore Granivore Granivore Nectarivore & Insectivore Nectarivore & Insectivore Nectarivore & Insectivore q q q q Insectivore,Omnivore q q q X Ground X Trees,Shrubs,Ground X Ground X Trees,Shrubs,Ground,Air X Trees,Shrubs,Air X Shrubs,Air X Trees,Shrubs,Ground,Air Red Wattlebird Little Wattlebird Striated Pardalote Welcome Swallow House Sparrow* Silvereye Willie Wagtail JS SW JH SW JMG JT JS (Yellow-orange belly, red wattles) (No orange on belly, no wattles) (Yellow face, black & white (Flies around ovals and other (Very small) (Silver ring around eye) (Black and white, tail wags from streaked crown, white wing streaks grassed areas, forked tail) side to side) with red spot) Nectarivore & Nectarivore & Insectivore Nectarivore & Insectivore Insectivore Granivore Omnivore Insectivore q q q Insectivore,Insectivore q q q q X Trees,Shrubs,Air X Trees,Shrubs,Air X Trees,Shrubs X Air X Ground X Trees,Shrubs X Ground,Air Common Blackbird* Common Starling* Australian Magpie Magpie-lark Little Raven Laughing Nankeen Kestrel Kookaburra JS JS JG JS JS JG JS (Smaller beak and body than (Breeding male black with bright yellow (Dark -

Contrasting Population Trends of Common Starlings (Sturnus Vulgaris) Across Europe

Ornis Fennica 96: 153–168. 2019 Contrasting population trends of Common Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) across Europe Henning Heldbjerg*, Anthony D. Fox, Aleksi Lehikoinen, Peter Sunde, Ainars Aunins, Dawn E. Balmer, Gianpiero Calvi, Tomasz Chodkiewicz, Przemek Chylarecki, Virginia Escandell, Ruud Foppen, Anna Gamero, Iordan Hristov, Magne Husby, Frederic Jiguet, Primo Kmecl, John A. Kålås, Lesley J. Lewis, Åke Lindström, Charlotte Moshøj, Renno Nellis, Jean-Y. Paquet, Danae Portolou, Jozef Ridzoò, Hans Schmid, Jana Skorpilová, Zoltán D. Szabó, Tibor Szép, Norbert Teufelbauer, Sven Trautmann, Chris van Turnhout, Zdenìk Vermouzek, Petr Voøíšek & Anne Weiserbs H. Heldbjerg, A.D. Fox & P. Sunde, Department for Bioscience, Aarhus University, Grenåvej 14, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] H. Heldbjerg & Charlotte Moshøj, DOF BirdLife Denmark, Vesterbrogade 140, 1620 Copenhagen, Denmark A. Aunins, Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, Faculty of Biology, University of Latvia; Jelgavas Street 1, Riga, LV-1004, Latvia and Latvian Ornithological Society, Skolas iela 3, Riga, LV-1010, Latvia D.E. Balmer, British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU, UK G. Calvi, Italian Common Breeding Bird Monitoring Programme, Studio Pteryx, Via Risorgimento 9, 20060 Basiano, Italy T. Chodkiewicz, Museum & Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warszawa, Poland and Polish Society for the Protection of Birds (OTOP), ul. Odrowaza 24, 05-270 Marki, Poland P. Chylarecki, Museum -

Ecology and Management of the Common Starling (Sturnus Vulgaris) in the Mclaren Vale Region

Ecology and Management of the Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) in the McLaren Vale Region FINAL REPORT to GRAPE AND WINE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Project Number: UA 01/05 Principal Investigator(s): David C Paton, Ronald G Sinclair & Christina M Bentz Research Organisation: University of Adelaide Date: August 19, 2005 PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Title page PRIMARY SUPERVISOR: DR DAVID C. PATON Environmental Biology, Benham Bldg DP312 School of Earth & Environmental Sciences University of Adelaide Adelaide, SA 5005 Ph (08) 8303 4742 Fax (08) 8303 6222 Email [email protected] CO-SUPERVISOR: DR RONALD G. SINCLAIR Senior Research Officer Animal & Plant Control Group Department of Water, Land & Biodiversity Conservation GPO BOX 2834 Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Ph (08) 8303 9506 Fax (08) 8303 9555 Email [email protected] CHIEF INVESTIGATOR: CHRISTINA BENTZ, M.SC. PhD Candidate Environmental Biology, Benham Bldg DP312 School of Earth & Environmental Sciences University of Adelaide Adelaide, SA 5005 Ph (08) 8303 3998 Mob (04) 2215 0586 Fax (08) 8303 6222 Email [email protected] 2 PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Table of Contents 1. Abstract.......................................................................................................................5 2. Executive summary.....................................................................................................6 2.1. Practical implications....................................................................................6 -

COR 089-2015, Starling Trapping Program

Se '~A COUNCIL REPORT ABBOTSFORD Report No. COR 089-2015 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Date: December 10, 2015 File No: 3900-20 To: Mayor and Council From: Bill Flitton, Director, Legislative Services/City Clerk Subject: Starling Trapping Program RECOMMENDATIONS 1. THAT the City of Abbotsford contribute $30,000 for a pilot Starling Management Program, operated by the local berry farming industry; 2. THAT staff be directed to engage the BC Blueberry Council, the BC Blueberry Growers Association, and other relevant agencies, to implement an industry operated Starling Management Program; and 3. THAT the operators of the program be requested to report back to Council in the Fall of 2016 regarding the effectiveness of the program. SUMMARY OF THE ISSUE Council, in March 2015, adopted an Audible Bird Scare Device Bylaw to deter Starlings from damaging crops; however, audible bird scare devices have limited effect on Starlings. Other options to deter Starlings include other bird scare devices or trapping of live birds. In February 2015, when considering further amendments and Three Readings of the Audible Bird Scare Device Bylaw, Council directed staff to report back to Council on a strategy on trapping juvenile Starlings. Staff waited until the end of the season and confirmation of trapping results before bringing forward a Starling trapping update to Council. BACKGROUND Starlings were originally a non-native species of bird to North America until in the late 1800s when some were released in Central Park in New York as part of the promotion of a William Shakespeare play. Eventually Starlings migrated to the west. Starlings began to re-emerge, after a brief absence, in the Pacific Northwest in the 1940s and now number in the millions.