Study on the Pelvic System of Birds and on the Origin of Flight Pauline Provini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Locomotion: Recent Advances and New Directions

MA07CH22-Lauder ARI 6 November 2014 13:40 Fish Locomotion: Recent Advances and New Directions George V. Lauder Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2015. 7:521–45 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on swimming, kinematics, hydrodynamics, robotics September 19, 2014 The Annual Review of Marine Science is online at Abstract marine.annualreviews.org Access provided by Harvard University on 01/07/15. For personal use only. Research on fish locomotion has expanded greatly in recent years as new This article’s doi: approaches have been brought to bear on a classical field of study. Detailed Annu. Rev. Marine. Sci. 2015.7:521-545. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org 10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015614 analyses of patterns of body and fin motion and the effects of these move- Copyright c 2015 by Annual Reviews. ments on water flow patterns have helped scientists understand the causes All rights reserved and effects of hydrodynamic patterns produced by swimming fish. Recent developments include the study of the center-of-mass motion of swimming fish and the use of volumetric imaging systems that allow three-dimensional instantaneous snapshots of wake flow patterns. The large numbers of swim- ming fish in the oceans and the vorticity present in fin and body wakes sup- port the hypothesis that fish contribute significantly to the mixing of ocean waters. New developments in fish robotics have enhanced understanding of the physical principles underlying aquatic propulsion and allowed intriguing biological features, such as the structure of shark skin, to be studied in detail. -

Longest Terrestrial Migrations and Movements Around the World Kyle Joly 1*, Eliezer Gurarie2, Mathew S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Longest terrestrial migrations and movements around the world Kyle Joly 1*, Eliezer Gurarie2, Mathew S. Sorum3, Petra Kaczensky 4,5, Matthew D. Cameron 1, Andrew F. Jakes6, Bridget L. Borg7, Dejid Nandintsetseg8,9, J. Grant C. Hopcraft10, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar11, Paul F. Jones12, Thomas Mueller8,9, Chris Walzer 5,13, Kirk A. Olson11, John C. Payne5,11,13, Adiya Yadamsuren14,15 & Mark Hebblewhite16 Long-distance terrestrial migrations are imperiled globally. We determined both round-trip migration distances (straight-line measurements between migratory end points) and total annual movement (sum of the distances between successive relocations over a year) for a suite of large mammals that had potential for long-distance movements to test which species displayed the longest of both. We found that caribou likely do exhibit the longest terrestrial migrations on the planet, but, over the course of a year, gray wolves move the most. Our results were consistent with the trophic-level based hypothesis that predators would move more than their prey. Herbivores in low productivity environments moved more than herbivores in more productive habitats. We also found that larger members of the same guild moved less than smaller members, supporting the ‘gastro-centric’ hypothesis. A better understanding of migration and movements of large mammals should aid in their conservation by helping delineate conservation area boundaries and determine priority corridors for protection to preserve connectivity. The magnitude of the migrations and movements we documented should also provide guidance on the scale of conservation eforts required and assist conservation planning across agency and even national boundaries. -

The Evolution of Micro-Cursoriality in Mammals

© 2014. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2014) 217, 1316-1325 doi:10.1242/jeb.095737 RESEARCH ARTICLE The evolution of micro-cursoriality in mammals Barry G. Lovegrove* and Metobor O. Mowoe* ABSTRACT Perissodactyla) in response to the emergence of open landscapes and In this study we report on the evolution of micro-cursoriality, a unique grasslands following the Eocene Thermal Maximum (Janis, 1993; case of cursoriality in mammals smaller than 1 kg. We obtained new Janis and Wilhelm, 1993; Yuanqing et al., 2007; Jardine et al., 2012; running speed and limb morphology data for two species of elephant- Lovegrove, 2012b; Lovegrove and Mowoe, 2013). shrews (Elephantulus spp., Macroscelidae) from Namaqualand, Loosely defined, cursorial mammals are those that run fast. South Africa, which we compared with published data for other However, more explicit definitions of cursoriality remain obscure mammals. Elephantulus maximum running speeds were higher than because locomotor performance is influenced by multiple variables, those of most mammals smaller than 1 kg. Elephantulus also including behaviour, biomechanics, physiology and morphology possess exceptionally high metatarsal:femur ratios (1.07) that are (Taylor et al., 1970; Garland, 1983a; Garland, 1983b; Garland and typically associated with fast unguligrade cursors. Cursoriality evolved Janis, 1993; Stein and Casinos, 1997; Carrano, 1999). In an in the Artiodactyla, Perissodactyla and Carnivora coincident with evaluation of these definition problems, Carrano (Carrano, 1999) global cooling and the replacement of forests with open landscapes argued that ‘…morphology should remain the fundamental basis for in the Oligocene and Miocene. The majority of mammal species, making distinctions between locomotor performance…’. -

Amphibious Fishes: Terrestrial Locomotion, Performance, Orientation, and Behaviors from an Applied Perspective by Noah R

AMPHIBIOUS FISHES: TERRESTRIAL LOCOMOTION, PERFORMANCE, ORIENTATION, AND BEHAVIORS FROM AN APPLIED PERSPECTIVE BY NOAH R. BRESSMAN A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVESITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Biology May 2020 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Miriam A. Ashley-Ross, Ph.D., Advisor Alice C. Gibb, Ph.D., Chair T. Michael Anderson, Ph.D. Bill Conner, Ph.D. Glen Mars, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my adviser Dr. Miriam Ashley-Ross for mentoring me and providing all of her support throughout my doctoral program. I would also like to thank the rest of my committee – Drs. T. Michael Anderson, Glen Marrs, Alice Gibb, and Bill Conner – for teaching me new skills and supporting me along the way. My dissertation research would not have been possible without the help of my collaborators, Drs. Jeff Hill, Joe Love, and Ben Perlman. Additionally, I am very appreciative of the many undergraduate and high school students who helped me collect and analyze data – Mark Simms, Tyler King, Caroline Horne, John Crumpler, John S. Gallen, Emily Lovern, Samir Lalani, Rob Sheppard, Cal Morrison, Imoh Udoh, Harrison McCamy, Laura Miron, and Amaya Pitts. I would like to thank my fellow graduate student labmates – Francesca Giammona, Dan O’Donnell, MC Regan, and Christine Vega – for their support and helping me flesh out ideas. I am appreciative of Dr. Ryan Earley, Dr. Bruce Turner, Allison Durland Donahou, Mary Groves, Tim Groves, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, UF Tropical Aquaculture Lab for providing fish, animal care, and lab space throughout my doctoral research. -

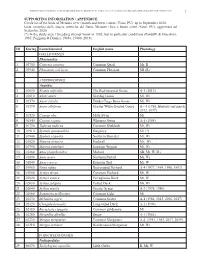

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I Hope You Have Fun Playing Birdwatching Bingo with Your Family

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I hope you have fun playing Birdwatching Bingo with your family. You can even share it with friends and do it over social media. To help you on your adventure, here is an identification sheet with all the different birds listed on your bingo card. With the help of this sheet and some binoculars, you will be on your way to becoming a fantastic birdwatcher. Most of these birds you can see visiting a birdfeeder, but some you might have to go on a walk and look for with a parent. To play, download and print the bingo cards for each player. Using pennies, pieces of paper, or even a pencil, mark the card when you see and identify the different birds. Don’t be frustrated if you don’t finish the game in one sitting, this game might be completed over a couple days. A great tool to help with IDing birds is the app MERLIN. This is a free bird ID app for your phone from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The website, www.allaboutbirds.org, is a great source too. Blue Jay - Scientific Name: Cyanocitta cristata - Identifiable Markings: o Blue above, light grey below. Black and white markings on wings and tail. Larger than a robin, smaller than a crow. Crest and long tail. - Photo: Females/Males Look Similar Brown-headed Cowbird - Scientific Name: Molothrus ater - Identifiable Markings: o Stout bill. Short tail and stocky body. Males are glossy black with chocolate brown head. Females are grey-brown overall, without bold streaks, but slightly paler throat. -

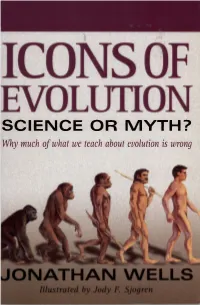

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

Wildlife Ecology Provincial Resources

MANITOBA ENVIROTHON WILDLIFE ECOLOGY PROVINCIAL RESOURCES !1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank: Olwyn Friesen (PhD Ecology) for compiling, writing, and editing this document. Subject Experts and Editors: Barbara Fuller (Project Editor, Chair of Test Writing and Education Committee) Lindsey Andronak (Soils, Research Technician, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) Jennifer Corvino (Wildlife Ecology, Senior Park Interpreter, Spruce Woods Provincial Park) Cary Hamel (Plant Ecology, Director of Conservation, Nature Conservancy Canada) Lee Hrenchuk (Aquatic Ecology, Biologist, IISD Experimental Lakes Area) Justin Reid (Integrated Watershed Management, Manager, La Salle Redboine Conservation District) Jacqueline Monteith (Climate Change in the North, Science Consultant, Frontier School Division) SPONSORS !2 Introduction to wildlife ...................................................................................7 Ecology ....................................................................................................................7 Habitat ...................................................................................................................................8 Carrying capacity.................................................................................................................... 9 Population dynamics ..............................................................................................................10 Basic groups of wildlife ................................................................................11 -

Are European Starlings Breeding in the Azores Archipelago Genetically Distinct from Birds Breeding in Mainland Europe? Verónica C

Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable To cite this version: Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable. Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (1), pp.95-100. 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x. hal-00535248 HAL Id: hal-00535248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535248 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:95–100 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x SHORT COMMUNICATION Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves & Kate Griffiths & Fiona R. Savory & Robert W. Furness & Barbara K. Mable Received: 6 May 2009 /Revised: 5 August 2009 /Accepted: 11 August 2009 /Published online: 29 August 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) has Keywords Azores . -

The Biodynamics of Arboreal Locomotion in the Gray Short

THE BIODYNAMICS OF ARBOREAL LOCOMOTION IN THE GRAY SHORT- TAILED OPOSSUM (MONODELPHIS DOMESTICA) A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Andrew R. Lammers August 2004 This dissertation entitled THE BIODYNAMICS OF ARBOREAL LOCOMOTION IN THE GRAY SHORT- TAILED OPOSSUM (MONODELPHIS DOMESTICA) BY ANDREW R. LAMMERS has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Audrone R. Biknevicius Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences LAMMERS, ANDREW R. Ph.D. August 2004. Biological Sciences The biodynamics of arboreal locomotion in the gray short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica). (147 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Audrone R. Biknevicius Most studies of animal locomotor biomechanics examine movement on a level, flat trackway. However, small animals must negotiate heterogenerous terrain that includes changes in orientation and diameter. Furthermore, animals which are specialized for arboreal locomotion may solve the biomechanical problems that are inherent in substrates that are sloped and/or narrow differently from animals which are considered terrestrial. Thus I studied the effects of substrate orientation and diameter on locomotor kinetics and kinematics in the gray short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica). The genus Monodelphis is considered the most terrestrially adapted member of the family Didelphidae, but nevertheless these opossums are reasonably skilled at climbing. The first study (Chapter 2) examines the biomechanics of moving up a 30° incline and down a 30° decline. Substrate reaction forces (SRFs), limb kinematics, and required coefficient of friction were measured. -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J.