In December, Claes Oldenburg Opens the Store I N New York's East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Ruling Requested by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel

JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF 31 JANUARY 1979<appnote>1</appnote> Yoshida GmbH v Industrie- und Handelskammer Kassel (preliminary ruling requested by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel) "Slide fasteners" Case 114/78 1. Goods — Slide fasteners — Origin — Determination thereof — Criteria — Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2067/77, Art. 1 — Invalid In adopting Regulation (EEC) No Regulation (EEC) No 802/68 of the 2067/77 concerning the determination of Council. Article 1 of Regulation No the origin of slide fasteners, the 2067/77 is therefore invalid. Commission exceeded its power under In Case 114/78 REFERENCE to the Court under Article 177 of the EEC Treaty by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel for a preliminary ruling in the action pending before that court between Yoshida GmbH, Mainhausen (Federal Republic of Germany) and Industrie- und Handelskammer Kassel on the validity of Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2067/77 concerning the determination of the origin of slide fasteners (Official Journal L 242 of 21 September 1977, p. 5), 1 — Language of the Case: German. 151 JUDGMENT OF 31. 1. 1979 — CASE 114/78 THE COURT composed of: H. Kutscher, President, J. Mertens de Wilmars and Lord Mackenzie Stuart (Presidents of Chambers), A. M. Donner, P. Pescatore, M. Sørensen, A. O'Keeffe, G. Bosco and A. Touffait, Judges, Advocate General: F. Capotorti Registrar: A. Van Houtte gives the following JUDGMENT Facts and Issues The facts of the case, procedure, origin certifying that its products are conclusions and submissions and of German origin or possibly of arguments of the parties may be Community origin. Whereas these certi• summarized as follows: ficates have hitherto been granted under Article 5 of Regulation (EEC) No I — Facts and procedure 802/68 of 27 June 1968 on the common definition of the concept of the origin of The plaintiff in the main action is a sub• goods in so far as the value of the raw sidiary of the Yoshida Kogyo K. -

Biography & Links

CLAES OLDENBURG 1929 Born in Stockholm, Sweden Education 1946 – 1950 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1950-1954 Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Selected Exhibitions 2013 Claes Oldenburg: The Street and The Store, MoMA, New York, NY Claes Oldenburg: The Sixties, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN Wood, Metal, Paint: Sculpture from the Fisher Collection, Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, Stanford, CA NeuenGalerie-neu gesehen: Sammlung + documenta-Erwerbungen, Neue Galerie, Kassel, Germany Pop Goes The Easel: Pop Art And Its Progeny, Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, CT The Pop Object: The Still Life Tradition in Pop Art, Acquavella Galleries, Inc., New York, NY 2012 Claes Oldenburg. The Sixties, UMOK ,Vienna, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the Museum of Modern Art New York, Walker Art Center, and the Ludwig Museum im Deutschherrenhaus. Claes Oldenburg, Pace Prints, New York, New York. Claes Oldenburg: Arbeiten auf Papier, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany Claes Oldenburg: Strange Eggs, The Menil Collection, Houston, TX Claes Oldenburg, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany Claes Oldenburg-From Street to Mouse: 1959-1970, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig-MUMOK, Vienna, Austria 2011 THE PRIVATE COLLECTION OF ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG, Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY Burning, Bright: A Short History of the Light Bulb, The Pace Gallery, New York, NY Contemporary Drawings from the Irving Stenn Jr. Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California, Norton Simon Museum -

KAWS Media Release

KAWS Media release 6 February–12 June 2016 Longside Gallery and open air Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) presents the first UK museum exhibition by KAWS, the renowned American artist, whose practice includes painting, sculpture, printmaking and design. The exhibition, in the expansive Longside Gallery and open air, features over 20 works: commanding sculptures in bronze, fibreglass, aluminium and wood alongside large, bright canvases immaculately rendered in acrylic paint – some created especially for the exhibition. The Park’s historically designed landscape becomes home to a series of monumental and imposing sculptures, including a new six-metre-tall work, which take KAWS’s idiosyncratic form of almost-recognisable characters in the process of growing up. Brooklyn-based KAWS is considered one of the most relevant artists of his generation. His influential work engages people across the generations with contemporary art and especially opens popular culture to young and diverse audiences. A dynamic cultural force across art, music and fashion, KAWS’s work possesses a wry humour with a singular vernacular marked by bold gestures and fastidious production. In the 1990s, KAWS conceived the soft skull with crossbones and crossed-out eyes which would become his signature iconography, subverting and abstracting cartoon figures. He stands within an art historical trajectory that includes artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Jeff Koons, developing a practice that merges fine art and merchandising with a desire to communicate within the public realm. Initially through collaborations with global brands, and then in his own right, KAWS has moved beyond the sphere of the art market to occupy a unique position of international appeal. -

FALKEN Is Now Main Sponsor of EWE Baskets Oldenburg

Offenbach am Main, March 2018 FALKEN is now main sponsor of EWE Baskets Oldenburg Tyre brand FALKEN is growing its involvement in team sports. As part of this strategy, the company is now the new main sponsor of the German Basketball Bundesliga (BBL) team, EWE Baskets Oldenburg. The north-west German club has notched up a career of successes at national and international level. The team plays in the easyCredit BBL as well as the international Basketball Champions League; currently Vice-Champions, they also won the German Cup in 2015 and were German Champions in 2009. The sponsorship agreement spans several years and is designed as a nationally based activation platform. In addition to stadium perimeter advertising, FALKEN holds the rights to present its logo on all sponsors’, advertising and display boards in and around the EWE Arena as well as broadcasting advertising commercials on the LED media display on the pitch and in the outer frame of the EWE Arena’s LED display. Sponsorship also includes access to players and partnership activities in digital media and social networks. “This partnership is a milestone for us”, says Dr. Claus Andresen, Head of Sales and authorised representative of EWE Baskets. “Falken Tyre will help us cement our position among the top names in basketball and support us in achieving our goals both on and off the pitch.” “The EWE Baskets are ideal partners for us at Falken Tyre”, explains Markus Bögner, Managing Director and COO of Falken Tyre Europe. “The club is synonymous with tradition, professionalism and inspiration – and that makes it a great fit for the FALKEN brand. -

Leitfaden Zur Familienforschung Im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg

Leitfaden zur Familienforschung im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg Leitfaden zur Familienforschung im NLA – Standort Oldenburg . Einleitung Die Hof- und Familienforschung wird immer beliebter. Die Frage nach dem „Wo komme ich eigentlich her?“ oder „wer waren meine Vorfahren und wie haben sie gelebt?“ weckt die Neugier in uns Menschen. Antworten darauf bieten zahlreiche Schätze in den Archiven. Bei der Familienforschung sammeln Sie unter anderem Daten zu Ihrer Familiengeschichte. Andere sammeln Briefmarken oder Münzen. Sie werden vieles über Verwandten und Vorfahren recherchieren und dabei Informationen zu Namen, Lebensdaten, Begebenheiten, Eigenarten, 2 Berufen, Ehrenämtern, finanziellen Verhältnissen, politischen Einstellungen etc. gewinnen - Sie unternehmen eine kleine „Zeitreise“. Die Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V. sieht ihre Aufgabe in der genealogischen Forschung vornehmlich im Kerngebiet des alten Herzogtums Oldenburg. Am jeden ersten Donnerstag im Monat bietet sie zwischen 14:00 und 18:00 Sprechstunden in den Räumen des Standorts Oldenburg an. Familienforscher können hier nicht nur wertvolle Tipps erhalten, sondern auch nützliche Kontakte zu anderen Forschern knüpfen. Die Internetadresse des Vereins ist: http://www.genealogy.net/vereine/OGF/ Im Folgenden erhalten Sie Informationen über die für Sie relevanten Bestände im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg sowie Hinweise für weiterführende Recherchen und hilfreiche Adressen. Sie können sich bereits von zu Hause aus im Archivinformationssystem Niedersachsen (Arcinsys) als Benutzer/-in registrieren und Recherchen in den Beständen des Landesarchivs durchführen (https://www.arcinsys.niedersachsen.de/arcinsys/start.action). Für weitere Fragen zu den einzelnen Beständen steht Ihnen auch gerne die Lesesaalaufsicht zur Verfügung! Bitte beachten Sie aber: Familienforschung ist gebührenpflichtig, die Tagesgebühr beträgt derzeit 10 € pro Person, außerdem sind 5er-Karten zum Preis von 30 € erhältlich (Stand: März 2015). -

Vereinbarung Nach

1. Fortschreibung zur Vereinbarung nach § 17 b Abs. 5 des Krankenhausfinanzierungsgesetzes (KHG) zur Umsetzung des DRG-Systemzuschlags-Gesetzes vom 5. Mai 2001 zwischen der Deutschen Krankenhausgesellschaft, Düsseldorf - nachfolgend DKG genannt - und dem AOK-Bundesverband, Bonn dem Bundesverband der Betriebskrankenkassen, Essen dem Bundesverband der Landwirtschaftlichen Krankenkassen, Kassel der Bundesknappschaft, Bochum dem IKK-Bundesverband, Bergisch Gladbach der See-Krankenkasse, Hamburg dem Verband der Angestelltenkrankenkassen, Siegburg dem Arbeiter-Ersatzkassen-Verband, Siegburg und dem Verband der Privaten Krankenversicherung, Köln - nachfolgend Spitzenverbände genannt – - gemeinsam – – 2 – 1. Fortschreibung zur Vereinbarung nach § 17 b Abs. 5 KHG zur Umsetzung des DRG-Systemzuschlags-Gesetzes § 1 Systemzuschlag 1. Nach § 1 Abs. 1 Satz 2 der Vereinbarung nach § 17 b Abs. 5 KHG zur Umset- zung des DRG-Systemzuschlags-Gesetzes vom 5. Mai 2001 wird folgender Satz eingefügt: „Für Krankenhäuser, die zum 1. Januar 2003 von ihrem in § 17b Abs. 4 Satz 4 KHG eingeräumten Optionsrecht Gebrauch gemacht haben, erfolgt die Erhebung des Zuschlages abweichend von Satz 2 analog der Fallzählung gemäß § 9 der Verordnung zum Fallpauschalensystem der Krankenhäuser (KFPV).“ 2. In § 1 Abs. 2 Satz 1 der Vereinbarung nach § 17 b Abs. 5 KHG zur Umsetzung des DRG-Systemzuschlags-Gesetzes vom 5. Mai 2001 werden nach dem Wort „Pflegesatzvereinbarung“ die Wörter „bzw. Budgetvereinbarung“ eingefügt. 3. § 1 Abs. 3 Satz 2 der Vereinbarung nach § 17 b Abs. 5 KHG zur Umsetzung des DRG-Systemzuschlags-Gesetzes vom 5. Mai 2001 wird wie folgt gefasst: „Er geht nicht in den Gesamtbetrag nach § 6 BPflV bzw. nach § 3 Abs. 2 Satz 1 KHEntgG ein und wird bei der Ermittlung der Erlösausgleiche nach den den §§ 11 Abs. -

Physical Restraint Use in Swiss Nursing Homes: Two

Innovation in Aging, 2020, Vol. 4, No. S1 665 PHYSICAL RESTRAINT USE IN SWISS NURSING PREVENTION AND REDUCTION OF CARE AGAINST HOMES: TWO NEW NATIONAL QUALITY SOMEONE’S WILL IN COGNITIVELY IMPAIRED INDICATORS PEOPLE AT HOME: A FEASIBILITY STUDY Lauriane Favez,1 Franziska Zúñiga,2 Catherine Blatter,1 Angela Mengelers,1 Michel Bleijlevens,1 Hilde Verbeek,1 Narayan Sharma,1 and Michael Simon,1 1. University of Vincent Moermans,2 Elizabeth Capezuti,3 and Jan Hamers,1 Basel, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland, 2. Basel University, 1. Maastricht University, Maastricht, Limburg, Netherlands, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland 2. Maastricht University, Riemst, Limburg, Belgium, Quality indicators are used in nursing homes to assess 3. Hunter College of CUNY, New York, New York, physical restraint use. Switzerland introduced two publicly United States reported indicators measuring the use of 1) bedrails and Sometimes care is provided to a cognitively impaired person 2) trunk fixation or seating that prevent standing up. Whether against the person’s will, referred to as involuntary treatment. these indicators show good between-provider variability is An intervention (PRITAH) was developed to prevent and re- unknown. The study aimed to measure the prevalence of duce involuntary treatment comprising 4 components: client- physical restraint use and assess their between-provider vari- centered care policy, workshops, coaching on the job by a ability using a cross-sectional, multicentre study of a con- specialized nurse and the use of alternative interventions. venience sample of nursing homes. The between-provider A feasibility study was conducted including 30 professional variability of the indicators was assessed with intraclass caregivers. -

Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Schloss

MUSEUMSLANDSCHAFT HESSEN KASSEL, SCHLOSS WILHELMSHÖHE, D-34131 KASSEL Postanschrift: Postfach 41 04 20, D-34066 Kassel Telefon: (05 61) 3 16 80-0 Fax: (05 61) 3 16 80-1 11 Email: [email protected] Gesamtverzeichnis lieferbarer Kataloge und Broschüren Stand: 11/2018 Aktuelle Ausstellungskataloge Bernd Zimmer - Kristallwelt. Ausstellungskatalog bearbeitet von Bernd Küster, 29,90 € Nina Schleif u. Gesa Wieczorek. Köln 2018. 191 S., 120 Abb. farbig Die Kunst zu sammeln. Die Städtische Kunstsammlung in Kassel. 19,80 € Ausstellungskatalog bearbeitet von Dorothee Gerkens, Henrike Hans u. a. Kassel 2018. 179 S., 140 Abb. farbig Groß gedacht! Groß gemacht? Landgraf Carl in Hessen und Europa. 39,90 € Ausstellungskatalog hrsg. von Gisela Bungarten. Kassel 2018. 624 S., über 700 Abb. farbig, über 50 Abb. s/w Schloss Friedrichstein in Bad Wildungen. Die Perle des Waldecker Landes. 19,80 € Katalog bearbeitet von Frank Pütz. Kassel u. Kromsdorf/Weimar 2017. 168 S., 168 Abb. farbig, 20 Abb. s/w Plakat Kunst Kassel. Ausstellungskatalog bearbeitet von Christiane Lukatis und 24,90 € Bernadette Winkler. Kassel 2016. 272 S., 146 Abb. farbig, 48 Abb. s/w Aus der Schatzkammer der Geschichte. Vom Mittelalter bis ins 19. Jahrhundert. 19,90 € Bestandskatalog bearbeitet von Antje Scherner und Stefanie Cossalter- Dallmann. Kassel 2016. 215 S., 167 Abb. farbig Mitten im Leben. Vom 19. bis ins 21. Jahrhundert. Bestandskatalog bearbeitet 19,90 € von Martina Lüdicke und Almut Kölsch. Kassel 2016. 146 Abb. farbig, 64 Abb. s/w Unter unseren Füßen. Altsteinzeit bis Frühmittelalter. Bestandskatalog 19,90 € bearbeitet von Irina Görner und Andreas Sattler. Kassel 2016. 186 Abb. farbig, 16 Abb. -

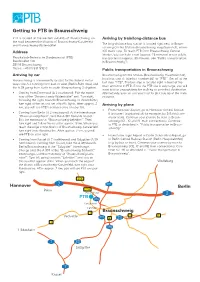

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig PTB is located on the western outskirts of Braunschweig, on Arriving by train/long-distance bus the road between the districts of Braunschweig-Kanzlerfeld The long-distance bus station is located right next to Braun- and Braunschweig-Watenbüttel. schweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), where Address ICE trains stop. To reach PTB from Braunschweig Central Station, you can take a taxi (approx. 15 minutes) or use public Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) transportation (approx. 30 minutes, see “Public transportation Bundesallee 100 in Braunschweig”). 38116 Braunschweig Phone: +49 (0) 531 592-0 Public transportation in Braunschweig Arriving by car Braunschweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), local bus stop A: take bus number 461 to “PTB”. Get off at the Braunschweig is conveniently located for the federal motor- last stop “PTB”. The bus stop is located right in front of the ways: the A 2 running from east to west (Berlin-Ruhr Area) and main entrance to PTB. Since the PTB site is very large, you will the A 39 going from north to south (Braunschweig-Salzgitter). want to plan enough time for walking to your final destination. • Coming from Dortmund (A 2 eastbound): Exit the motor- Alternatively, you can ask your host to pick you up at the main way at the “Braunschweig-Watenbüttel” exit. Turn right, entrance. following the signs towards Braunschweig. In Watenbüttel, turn right at the second set of traffic lights. After approx. 2 Arriving by plane km, you will see PTB‘s entrance area on your left. • From Hannover Airport, go to Hannover Central Station • Coming from Berlin (A 2 westbound): At the interchange (Hannover Hauptbahnhof) for example, by S-Bahn (com- “Braunschweig-Nord”, take the A 391 towards Kassel. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

A Study on Connectivity and Accessibility Between Tram Stops and Public Facilities: a Case Study in the Historic Cities of Europe

Urban Street Design & Planning 73 A study on connectivity and accessibility between tram stops and public facilities: a case study in the historic cities of Europe Y. Kitao1 & K. Hirano2 1Kyoto Women’s University, Japan 2Kei Atelier, Yame, Fukuoka, Japan Abstract The purpose of this paper is to understand urban structures in terms of tram networks by using the examples of historic cities in Europe. We have incorporated the concept of interconnectivity and accessibility between public facilities and tram stops to examine how European cities, which have built world class public transportation systems, use the tram network in relationship to their public facilities. We selected western European tram-type cities which have a bus system, but no subway system, and we focused on 24 historic cities with populations from 100,000 to 200,000, which is the optimum size for a large-scale community. In order to analyze the relationship, we mapped the ‘pedestrian accessible area’ from any tram station in the city, and analyzed how many public facilities and pedestrian streets were in this area. As a result, we were able to compare the urban space structures of these cities in terms of the accessibility and connectivity between their tram stops and their public facilities. Thus we could understand the features which determined the relationship between urban space and urban facilities. This enabled us to evaluate which of our target cities was the most pedestrian orientated city. Finally, we were able to define five categories of tram-type cities. These findings have provided us with a means to recognize the urban space structure of a city, which will help us to improve city planning in Japan. -

Frankfurt, Den 25

ERGEBNISDOKUMENTATION ERSTE KONFERENZ AM 22.11.2017 ZUR FORTSCHREIBUNG DES KOMMUNALEN ALTENPLANS PRIORISIERUNG DER MASSNAHMEN IN DEN FÜNF ZENTRALEN ENTWICKLUNGSBEREICHEN IM AUFTRAG DER STADT OFFENBACH AM MAIN | SOZIALAMT | KOMMUNALE ALTENPLANUNG STAND 15.01.2018 .................................................................................................................................................................. MODERATION | KOKONSULT KRISTINA OLDENBURG | [email protected] INHALT Teilnehmerliste ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Einführung ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Gruppendiskussionen an Thementischen nach den fünf Entwicklungsbereichen .......................... 5 3. Ergebnisse der Arbeitsgruppen ....................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Entwicklungsbereich Erwerbstätigkeit, Beschäftigung und Sicherung im Alter ........................ 6 3.2 Entwicklungsbereich Soziale Teilhabe – offene Seniorenarbeit ............................................... 8 3.3 Entwicklungsbereich Information – Vernetzung ........................................................................ 9 3.4 Entwicklungsbereich Wohnen und Stadtgestaltung ................................................................ 11 3.5 Entwicklungsbereich Sozialraumorientierung