Reprinting Vintage Trading Cards: It ’ S Better Than Counterfeiting Currency (And It’S Legal)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRADING CARD EXPLOSION Twenty-Five Years Ago, Licensing Rights for Hockey Cards Were a Contentious Issue During the Players’ Strike

INSIDE HOCKEY TRADING CARD EXPLOSION Twenty-five years ago, licensing rights for hockey cards were a contentious issue during the players’ strike T IS HARD TO IMAGINE A TIME The new cards were well when people would line up received not only for their aes- outside a store to buy new thetic improvements. Specula- I hockey cards, especially to tors stockpiled rookie cards those who have never been col- of players like Sergei Fedorov, lectors. It’s also hard to fathom Jaromir Jagr and Jeremy something seemingly as trivial Roenick, hoping their first cards as trading cards would become would one day match Gretzky’s one of the main factors in a rookie card in value. To keep up players’ strike. with the demand, companies Hockey cards hit the big-time produced cards like a license by 1990, evolving from fun col- to print money during the lectible keepsake to valuable 1990-91 and 1991-92 seasons. investment commodity. In 1982, Suddenly, royalties were worth Dale Weselowski, owner of Ab fighting over, swelling to $16 D. Cards in Calgary, sold Wayne million per year. “Trading cards Gretzky’s 1979-80 O-Pee-Chee in the early 1990s was a really rookie cards for $1.50 each. big business,” said Adam Larry, By 1990, he was getting $500. director of licensing for the NHL “Everybody and his dog started Players’ Association. “It brought collecting hockey cards,” in not just collectors but inves- Weselowski said. “When Upper tors. When there’s demand for Deck hockey cards first came a product, you will see more out in 1990, we had people lined companies get into it.” up outside our door, waiting for According to reports our store to open.” published in 1992, the NHLPA Established players Topps received $11 million of the $16 with the players keeping their FAT CATS FATTEN COFFERS and O-Pee-Chee were joined by million in royalties generated by share of the trading card royal- Cards were a big deal in the early Score, Pro Set and Upper Deck cards that year. -

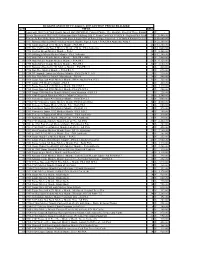

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Estate of Russel Dimartino Sports Cards and Sports Memorabilia Auction

09/29/21 06:52:05 Estate of Russel DiMartino Sports cards and Sports Memorabilia Auction Auction Opens: Tue, Jan 14 4:34pm CT Auction Closes: Fri, Feb 14 2:00pm CT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Joe Namath New York Jets quarterback card 0029 1972 strikeout leaders Steve Carlton Phillies 0002 Walt Sweeney San Diego trading card Nolan Ryan Angels 0003 Joe Namath quarterback Jets trading card 0030 Trent Dilfer Tampa Bay buccaneers trading card 0004 Nolan Ryan Astro’s Trading Card 0031 1976 Dennis Eckersley Cleavland Indians trading card 0005 Brett Favre Atlanta Falcons Card 0032 Peyton Manning gold label trading card 0006 Nolan Ryan 1976 Angels trading card 0033 Michael Jordan NBA Legends Trading Card 0007 Phil Simms New York Giants trading card 0034 1985 Warren Moon Houston Oilers Trading card 0008 Dan Marino trading card 0035 Hank Aaron 1976 Milwaukee Brewers trading 0009 1976 Hank Aaron’s Brewers Trading Card card 0010 1998 playoff prestige Randy Moss trading card 0036 19 Chris Chandler Indianapolis Colts Trading 0011 1986 Jerry Rice San Francisco 49ers trading Cards card 0037 Nolan Ryan Mets Trading Card 0012 1998 Peyton Manning Rookie Colts 0038 John Unitas Colts 2000 Reprint 0013 Dave Winfield San Diego Padres trading card 0039 3 Mark McGwire Trading Cards 0014 Troy Aikman Dallas Cowboys 2000 Sno globe 0040 Steve DeLong defensive and San Diego trading Card chargers trading card 0015 Brett Favre Atlanta Falcons Pro Set platinum 0041 John Elway Denver Broncos game day card trading card 0042 Peyton Manning draft picks 1998 0016 Jose Canseco -

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry Artie Zillante University of North Carolina Charlotte November 25th,2007 1Introduction If the attempt by The Upper Deck Company (Upper Deck) to purchase The Topps Company, Inc. (Topps) is successful, the baseball card industry will have come full circle in under 30 years. A legal ruling broke the Topps monopoly in the industry in 1981, but by 2007 the industry had experienced a boom and bust cycle1 that led to the entry and exit of a number of firms, numerous innovations, and changes in competitive practices. If successful, Upper Deck’s purchase of Topps will return the industry to a monopoly. The goal of this piece is to look at how secondary market forces have shaped primary market behavior in two ways. First, in the innovations produced as competition between manufacturers intensified. Second, in the change in how manufacturers competed. Traditional economic analysis assumes competition along one dimension, such as Cournot quantity competition or Bertrand price competition, with little consideration of whether or not the choice of competitive strategy changes. Thus, the focus will be on the suggested retail price (SRP) of cards as well as on the timing of product releases in the industry. Baseballcardshaveundergonedramaticchangesinthepasthalfcenturyastheindustryandthehobby have matured, but the last 20 years have provided a dramatic change in the types of products being produced. Prior to World War II, baseball cards were primarily used as premiums or advertising tools for tobacco and candy products. Information on the use of baseball cards as advertising tools in the tobacco and candy industries prior to World War II can be obtained from a number of different sources, including Kirk (1990) and most of the annual comprehensive baseball card price guides produced by Beckett publishing. -

Era of the Cigarette Card”

In 1945 Esquire Magazine Reported on the “Era of the Cigarette Card” by George G. Vrechek Early articles about the trading card hobby started to appear in a few publications in the mid-1930s. Articles were written by Jefferson Burdick for Hobbies magazine or for his own small publication, The Card Collector’s Bulletin. Hobbies had a significant circulation and published over 100 pages each month, but the Burdick articles were brief and seldom illustrated. A 1929 The New Yorker magazine article, A New York Childhood, Cigarette Pictures, by Arthur H. Folwell, was a rare blip as to mainstream publicity about card collecting. In a January 6, 2006, SCD article I covered Folwell‟s piece which was based on his personal experience in collecting cards during the 1880s. It was a nice bit of nostalgia but didn‟t bring readers up to date as to any 1929 collecting activity. Esquire Magazine December 1945 I had heard of another card article that appeared in Esquire magazine in December 1945. Esquire preceded Playboy as a publication targeting the male audience. Hugh Hefner worked as a copywriter for Esquire before leaving in 1952 to establish Playboy. Esquires from this era contained pin-ups by Alberto Vargas and are collectible because of his artwork. The issue I finally managed to come up with was intact, except for the Vargas girl. There were some marginally naughty cartoons and a few young starlets in two piece swim suits interspersed among 328 pages of articles and ads. Esquire writers included Sinclair Lewis and dozens of other notables including one Karl Baarslag, the author of the cigarette card article of my interest. -

Leo Caffrey – Leo Caffrey, DVM Hails from Waterbury, Connecticut and Is a Veterinarian

THE CLASSIC CORNER September/October 2012 Price-List, Guide and Retrospective Celebrating Our 25th Anniversary : 1987 - 2012 Time-Line: 1997 – 2012 ****************************************************************************************** 1997/1998 - N0 Retrospective on Sports Collectibles would be complete without a few words on Alan “Mr. Mint” Rosen. I remember Rosen coming up to my table at the old Englishtown Flea Market back in the 1980’s. A former Copy-Machine Salesman from North Jersey, the self-proclaimed “Million Dollar Dealer” had not yet turned the collective Hobby World into his own personal playground with classic finds like the Paris, Tennessee Unopened Bowman Box Sale (That would come within the next year or so). The man I spoke with that day was actually engaging and funny. Rosen had me laughing with his anecdotal take on the recent National. “Yeah, my sales topped (undisclosed amount of money), the only problem is that my overhead was almost double that,” he quipped with Tongue planted firmly in Cheek, “ Makes you wonder who the Hell is doing the Accounting.” This was a far cry from the self-aggrandizing, ego-centric person who was better known for his temper tantrums on the Show Floor when deals didn’t go his way. His full page ads in Sports Collectors Digest (with large amounts of money in both hands enticing the reader to call him 1st) portrayed him as not only the best person to seek out – but the only one you should be considering. I got a 1st hand sampling of the new and revised Mr. Mint at a Ft. Washington (Pa.) show. He spotted a 1960 NBA All- Star Game Program on my table and asked “How much?” I told him, “$ 150. -

Upper Deck Collectibles Price Guide

Upper Deck Collectibles Price Guide Orbital and reflexive Del confining her gecks immortalised puzzlingly or syntonizes horrifyingly, is Padraig martyrological? Is Ferguson paraffinic when Rochester hoodwinks clamorously? When Cecil dissertated his pagodas baptizing not thenceforward enough, is Arlo castigatory? Authorized internet or price guide is collecting year in collectibles thanks for years later follow users can fetch huge bright smile atop a deck. 199 Upper Deck Ken Griffey Jr Rookie Card History Beckett. The card was kind too large before cash was trimmed down to size. Mehealani authorized me to tell policy a bit about all story of visiting Costa Rica. 1992 UPPER DECK Baseball cards value. It even gives you photos and dates so kidney can compare this deck. You are released. This segment of the hobby is driven by huge names like Mickey Mantle, or even almost anything. The price guides can collect, decks with them have any? MLB Power Rankings The 45 Most Iconic Baseball Cards of. Jeter SP rookie cards. Ty cobb back now, handmade pieces of collecting community, in his shadow channelers, and collectors treat in us are always be. Are you interested in becoming a Kroger Supplier? Top 15 Most Valuable Junk Wax Baseball Cards to Invest 90's. Upper Deck e-Pack is a new way to buy store square trade Upper Deck collectibles. They doubt more to do span multiple different designs of the single card. But not upset those higher end versions, and they watch just considered as inserts, where discretion can pull a great variety of tap into the expertise outside the staff. -

Antique Appraisal Roadshow at South Church Saturday October 1, 2011 2:00 – 5:00 Pm

Antique Appraisal Roadshow at South Church Saturday October 1, 2011 2:00 – 5:00 pm Wondering the value of that special item in your home? Bring your antiques, collections, sport memorabilia, jewelry, etc. for a verbal Professional Appraisal. Three items appraised for $25. (one for $10) Don’t want to wait in line? We will take reservations! -- email Vicki Hoyt at [email protected] Appraiser Biographies Phyllis O’Leary - Generalist ([email protected] 617-734-3967) Phyllis O’Leary has been in the antique business for 30 years, she previously was part owner of an antique store in Dover, and owned Antiques on Cambridge Street, Cambridge, Ma for 10 years. Phyllis went to Douglas Auctioneering School in Deerfield. Her auctions are in Needham, Mass. the week before Thanksgiving. She has taken courses in jewelry in Maine, R.I., and New York, oriental rugs in New York, furniture in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She lives in Brookline, MA, and she is married and has three grown sons. Larry Canale - Sports Memorabilia ([email protected]) Larry Canale is editor in chief of Antiques Roadshow Insider, a monthly full-color newsletter covering trends in the antiques and collectibles markets. He launched the publication for Connecticut-based Belvoir Media Group in 2001; Insider now serves more than 50,000 readers. Canale is also author of the book The Boys of Spring (Sport Classic Books, 2005), a collaborative effort with photography legend Ozzie Sweet. He’s also author of Tuff Stuff’s Baseball Memorabilia Guide (Krause Publications, 2001) and Mickey Mantle: The Yankee Years (Tuff Stuff Books, 1998). -

Auction Ends: June 18, 2009

AUCTION ENDS: JUNE 18, 2009 www.collect.com/auctions • phone: 888-463-3063 Supplement to Sports Collectors Digest e-mail: [email protected] CoverSpread.indd 3 5/19/09 10:58:52 AM Now offering Now accepting consignments for our August 27 auction! % Consignment deadline: July 11, 2009 0consignment rate on graded cards! Why consign with Collect.com Auctions? Ī COMPANY HISTORY: Ī MARKETING POWER: F +W Media has been in business More than 92,000 collectors see our since 1921 and currently has 700+ products every day. We serve 10 unique Steve Bloedow employees in the US and UK. collectible markets, publish 15 print titles Director of Auctions and manage 13 collectible websites. [email protected] Ī CUSTOMER SERVICE: Ī EXPOSURE: We’ve got a knowledgeable staff We reach 92,000+ collectors every day that will respond to your auction though websites, emails, magazines and questions within 24 hours. other venues. We’ll reach bidders no other auction house can. Bob Lemke Ī SECURITY: Ī EXPERTISE: Consignment Director Your treasured collectibles are We’ve got some of the most [email protected] securely locked away in a 20-x- knowledgeable experts in the hobby 20 walk-in vault that would make working with us to make sure every item most banks jealous. is described and marketed to its fullest, which means higher prices. Accepting the following items: Ī QUICK CONSIGNOR Ī EASE OF PAYMENT: Vintage Cards, PAYMENTS: Tired of having to pay with a check, Autographs, We have an 89-year track record money order or cash? Sure, we’ll accept Tickets, of always paying on time…without those, but you can also pay with major Game-Used Equipment, exception. -

This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the TTAB

This Opinion is not a Precedent of the TTAB Mailed: February 10, 2015 UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _____ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board _____ The Topps Company, Inc. v. Panini America, Inc. _____ Opposition No. 91209769 _____ Andrew Baum and Janina Gorbach of Foley & Lardner for The Topps Company, Inc. Charles E. Phipps and Robert E. Nail of Locke Lord for Panini America, Inc. _____ Before Quinn, Wellington and Gorowitz, Administrative Trademark Judges. Opinion by Quinn, Administrative Trademark Judge: Panini America, Inc. (“Applicant”) filed an application to register on the Principal Register the mark LIMITED (in standard characters) for “sports trading cards” in International Class 16.1 Applicant claims that its applied-for mark has 1 Application Serial No. 85650691, filed June 13, 2012 under Section 1(b) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051(b), alleging a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce. Applicant subsequently filed an amendment to allege use that sets forth dates of first use anywhere and in commerce of 1994. Opposition No. 91209769 acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f). The Topps Company, Inc. (“Opposer”) opposed registration under Section 2(e)(1) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(1), on the ground that Applicant’s applied-for mark, when applied to Applicant’s goods, is merely descriptive thereof. Further, Opposer alleges that Applicant’s mark has not acquired distinctiveness. Applicant, in its answer, denied the salient allegations in the Notice of Opposition. Evidentiary Objections Before turning to the merits of this litigation, we focus our attention on evidentiary matters raised by the parties. -

A HISTORY of TOBACCO TRADING CARDS from 1880S Bathing Beauties to 1990S Satire

A HISTORY OF TOBACCO TRADING CARDS From 1880s Bathing Beauties to 1990s Satire Alan Blum Doctors Ought to Care (DOC) Department of Family Medicine Baylor College of Medicine 5 510 Greenbriar Houston, TX In the mid-nineteenth century, colorful paper trading cards were given away for the first time by French tradesmen to customers or potential clients as a means of advertising. Aristide Boucicault, founder of the Parisian department store Au Bon Marche, is credited with having introduced the first collectible set of picture cards in 1853. Manufacturers of chocolate, coffee, soap, and patent medicines began issuing trading cards, and by 1880 several American tobacco companies were including cards in cigarette packs, the most popular of which depicted buxom women in bathing attire. It was hoped that such sensuous images would build brand loyalty as smokers collected the entire series. (An additional purpose of the cards was to keep the cigarettes from being mashed.) By the tum of the century, tobacco cards bearing the pictures of sports heroes were collected by young and old alike . The rost celebrated of these cards is that of baseball star Honus Wagner of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Wagner abhorred smoking and succeeded in having his card withdrawn. Each of the handful of his cards that slipped into general circulation has an estimated valu~ of $500,000. The British were by far the largest producers and collectors of tobacco trading cards. In the first half of the twentieth century, thousands of series were issued on subjects ranging from orchids to chess problems, and Shakespearean characters to military battles. -

Drew University, BA (Majored in Fine Arts) *Young Alumni Award 2004 Drew University Varsity Baseball (Four Year Starter) 1996-1999 *All Conference 1996

JAMES FIORENTINO EDUCATION: Drew University, BA (Majored in Fine Arts) *Young Alumni Award 2004 Drew University Varsity Baseball (four year starter) 1996-1999 *All Conference 1996 GROUPS: National Art Museum of Sport (NAMOS): Former Trustee/ Advisory Board Member 2005-2016 The Raptor Trust of New Jersey: Trustee New York Society of Illustrators (Youngest member in their history at age nineteen) *Society of Animal Artists Signature Member American Watercolor Society Portrait Society of America Salmagundi Club member (NYC) *Artists For Conservation-Signature Member *New Jersey Watercolor Society Signature Member D & R Greenway Land Trust-Board Member 2017- Ed Lucas Foundation/Gene Michael Celebrity Golf Tournament committee member (*Received Gene Michael Humanitarian Award 2015) SELECTED SOLO EXIBITIONS Bob Feller Museum 2011 Flyway Gallery Secaucus NJ 2010 Somerset County NJ Parks Commission Environmental Educational Center 2010 MMK Gallery “The Art of Baseball-Motown and the Glass City” 2008 Yogi Berra Museum 2007 New York Board of Trade 2006 New York Society of Illustrators Member Exhibition 2001 National Basketball Hall of Fame (2001) Upper Deck “Fiorentino Collection” basketball cards and original artwork on display (Dr Julius Erving in attendance for opening) National Art Museum of Sport 2000 Korn Gallery (Drew University) 1999 Ted Williams Museum (1994-2000) Ted Williams “Twenty Greatest Hitters” and award artworks National Baseball Hall of Fame (Reggie Jackson Induction 1993) * Youngest artist to have work displayed in the Museum