This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the TTAB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

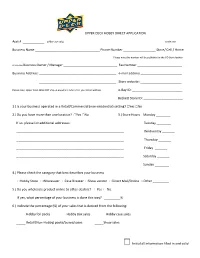

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct # ____________ (office use only) circle one Business Name ____________________________________ Phone Number __________________ Store/ Cell / Home Please note this number will be published in the UD Store locator circle one Business Owner / Manager ______________________________ Fax Number _________________________ Business Address: ___________________________________________ e‐mail address _______________________ ___________________________________________ Store website: _______________________ Please note, Upper Deck WILL NOT ship to anywhere other than your Retail address e‐Bay ID: ____________________________ Beckett Store ID: ______________________ 1.) Is your business operated in a Retail/Commercial (non‐residential) setting? ☐Yes ☐No 2.) Do you have more than one location? ☐Yes ☐No 3.) Store Hours Monday ________ If so, please list additional addresses: Tuesday ________ ____________________________________________________________ Wednesday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Thursday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Friday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Saturday _______ Sunday ________ 4.) Please check the category that best describes your business ☐Hobby Store ☐Wholesaler ☐Case Breaker ☐Show vendor ☐Direct Mail/Online ☐Other _________ 5.) Do you wholesale product online to other dealers? ☐ Yes ☐ No. If yes, what percentage of your business is done this way? _________% 6.) Indicate the -

TRADING CARD EXPLOSION Twenty-Five Years Ago, Licensing Rights for Hockey Cards Were a Contentious Issue During the Players’ Strike

INSIDE HOCKEY TRADING CARD EXPLOSION Twenty-five years ago, licensing rights for hockey cards were a contentious issue during the players’ strike T IS HARD TO IMAGINE A TIME The new cards were well when people would line up received not only for their aes- outside a store to buy new thetic improvements. Specula- I hockey cards, especially to tors stockpiled rookie cards those who have never been col- of players like Sergei Fedorov, lectors. It’s also hard to fathom Jaromir Jagr and Jeremy something seemingly as trivial Roenick, hoping their first cards as trading cards would become would one day match Gretzky’s one of the main factors in a rookie card in value. To keep up players’ strike. with the demand, companies Hockey cards hit the big-time produced cards like a license by 1990, evolving from fun col- to print money during the lectible keepsake to valuable 1990-91 and 1991-92 seasons. investment commodity. In 1982, Suddenly, royalties were worth Dale Weselowski, owner of Ab fighting over, swelling to $16 D. Cards in Calgary, sold Wayne million per year. “Trading cards Gretzky’s 1979-80 O-Pee-Chee in the early 1990s was a really rookie cards for $1.50 each. big business,” said Adam Larry, By 1990, he was getting $500. director of licensing for the NHL “Everybody and his dog started Players’ Association. “It brought collecting hockey cards,” in not just collectors but inves- Weselowski said. “When Upper tors. When there’s demand for Deck hockey cards first came a product, you will see more out in 1990, we had people lined companies get into it.” up outside our door, waiting for According to reports our store to open.” published in 1992, the NHLPA Established players Topps received $11 million of the $16 with the players keeping their FAT CATS FATTEN COFFERS and O-Pee-Chee were joined by million in royalties generated by share of the trading card royal- Cards were a big deal in the early Score, Pro Set and Upper Deck cards that year. -

Each Hobby Box of 2019 Topps Allen & Ginter Delivers 3

HOBBY EACH HOBBY BOX OF 2019 TOPPS ALLEN & GINTER DELIVERS 3 HITS, INCLUDING ON-CARD AUTOGRAPHS, RELICS, ORIGINAL A&G BUYBACKS, BOOK CARDS, CUT SIGNATURES, AND RIP CARDS! Base Card – Mini Wood Parallel Star Signs Insert Base Card Celebrating the world’s greatest champions and most iconic figures, Topps Allen & Ginter returns in July 2019. BASE CARDS BASE CARDS – Featuring 300 of the top MLB® stars, Rookies and retired greats, as well as non-baseball champions. • Silver Portrait Parallel - GINTER HOT BOX ONLY • Glossy Parallel – Numbered 1-of-1 BASE CARD SHORT PRINTS – 50 subjects not found in the base set. • Silver Portrait Parallel - GINTER HOT BOX ONLY • Glossy Parallel – Numbered 1-of-1 Base Card – Full-Size BASE CARDS MINI CARDS • Base Mini Parallel – 1 per pack • Allen & Ginter Parallel – 1:5 packs • Black Bordered – 1:10 packs • No Number – Limited to 50 • Brooklyn Back – Numbered to 25 • Wood – Numbered 1-of-1 HOBBY ONLY • Glossy – Numbered 1-of-1 MINI CARDS SHORT PRINT • Base Mini Parallel – 1:13 packs • Allen & Ginter Parallel – 1:65 packs • Black Bordered – 1:30 packs • No Number – Limited to 50 • Brooklyn Back – Numbered to 25 • Wood – Numbered 1-of-1 HOBBY ONLY • Glossy – Numbered 1-of-1 MINI SIZED METALS • 150 subjects – limited to 3 HOBBY ONLY Base Card – Mini Base Card Mini Base Card – Black Border Parallel Mini Wood Parallel NEW! MINI STAINED GLASS VARIATIONS • 150 subjects – limited to 25 FRAMED MINI PARALLELS • Printing Plates – Numbered 1-of-1 • Cloth Cards – Numbered to 10 HOBBY ONLY RELIC CARDS & ORIGINALS ALLEN & GINTER FULL-SIZE RELICS – Featuring MLB® Players, world champion athletes, and personalities. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

THE LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England

THE LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] POSTAL AUCTION ENDING 30TH APRIL 2016 CATALOGUE OF CIGARETTE & TRADE CARDS & OTHER CARTOPHILIC ITEMS TO BE SOLD BY POSTAL AUCTION Bids can be submitted by post, phone, fax, e-mail or through our website. Estimates include VAT. Successful bidders outside the European Community will have 15% (UK tax) deducted from prices realized. Abbreviations used: FCC = Finest Collectable Condition; VG = Very Good; G = Good; F = Fair; P = Poor; VP = Very Poor; O/W = Otherwise; EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (89 x 64mm) L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature; Type Card = one card from a set; 27/50 = 27 cards out of a set of 50 etc; EST in end column = Estimated Value. See biding sheet for conditions of sale. Last date for receipt of bids Saturday 30th April. There are no additional charges to bidders for buyers premium etc. LOT ISSUER DESCRIPTION CONDITION EST 1 IMPEL/PACIFIC USA 2LT Sets Laffs, The College Years Saved by the Bell 1991-94……………………………………………… Mint £16 2 A & M WIX Set 250 Cinema Cavalcade 1st Series (mixed sizes as issued) 1939………….. Few creased, some F O/W G-VG £250 3 TYPHOO TEA Set 25 Common Objects Highly Magnified 1925…………………………………………………….. 1G O/W VG-FCC £40 4 WILLS 12/100 Soldiers of the World ‘Ld’ back thick card 1895…………………………………………………………… P-F £30 5 SKYBOX/RITTENHOUSE 2LT Sets Gargoyles Series 2, Conan Art of the Hyborian Age 1996-2004……………………………… Mint £21 6 PARKHURST Canada M79/100 Birds c1950………………………………………………………………………………. -

Dec Pages 79-84.Qxd 8/5/2019 12:45 PM Page 1

ASC080119_080_Dec Pages 79-84.qxd 8/5/2019 12:45 PM Page 1 All Star Cards To Order Call Toll Free Page 86 15074 Antioch Road Overland Park, KS 66221 www.allstarcardsinc.com (800) 932-3667 BOXING 1927-30 EXHIBITS: 1938 CHURCHMAN’S: 1951 TOPPS RINGSIDE: 1991 PLAYERS INTERNATIONAL Dempsey vs. Tunney “Long Count” ...... #26 Joe Louis PSA 8 ( Nice! ) Sale: $99.95 #33 Walter Cartier PSA 7 Sale: $39.95 (RINGLORDS): ....... SGC 60 Sale: $77.95 #26 Joe Louis PSA 7 $69.95 #38 Laurent Dauthuille PSA 6 $24.95 #10 Lennox Lewis RC PSA 9 $17.95 Dempsey vs. Tunney “Sparing” ..... 1939 AFRICAN TOBACCO: #10 Lennox Lewis RC PSA 8.5 $11.95 ....... SGC 60 Sale: $77.95 NEW! #26 John Henry Lewis PSA 4 $39.95 1991 AW SPORTS BOXING: #13 Ray Mercer RC PSA 10 Sale: $23.95 #147 Muhammad Ali Autographed (Black #14 Michael Moorer RC PSA 9 $14.95 1935 PATTREIOUEX: 1948 LEAF: ....... Sharpie) PSA/DNA “Authentic” $349.95 #31 Julio Cesar-Chavez PSA 10 $29.95 #56 Joe Louis RC PSA 5 $139.95 #3 Benny Leonard PSA 5 $29.95 #33 Hector “Macho” Camacho PSA 10 $33.95 #78 Johnny Coulon PSA 5 $23.95 1991 AW SPORTS BOXING: #33 Hector “Macho” Camacho PSA 9 $17.95 1937 ARDATH: 1950 DUTCH GUM: #147 Muhammad Ali Autographed (Black NEW! Joe Louis PSA 7 ( Tough! ) $99.95 ....... Sharpie) PSA/DNA “Authentic” $349.95 1992 CLASSIC W.C.A.: #D18 Floyd Patterson RC PSA $119.95 Muhammad Ali Autographed (with ..... 1938 CHURCHMAN’S: 1951 TOPPS RINGSIDE: 1991 PLAYERS INTERNATIONAL ...... -

Estate of Russel Dimartino Sports Cards and Sports Memorabilia Auction

09/29/21 06:52:05 Estate of Russel DiMartino Sports cards and Sports Memorabilia Auction Auction Opens: Tue, Jan 14 4:34pm CT Auction Closes: Fri, Feb 14 2:00pm CT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Joe Namath New York Jets quarterback card 0029 1972 strikeout leaders Steve Carlton Phillies 0002 Walt Sweeney San Diego trading card Nolan Ryan Angels 0003 Joe Namath quarterback Jets trading card 0030 Trent Dilfer Tampa Bay buccaneers trading card 0004 Nolan Ryan Astro’s Trading Card 0031 1976 Dennis Eckersley Cleavland Indians trading card 0005 Brett Favre Atlanta Falcons Card 0032 Peyton Manning gold label trading card 0006 Nolan Ryan 1976 Angels trading card 0033 Michael Jordan NBA Legends Trading Card 0007 Phil Simms New York Giants trading card 0034 1985 Warren Moon Houston Oilers Trading card 0008 Dan Marino trading card 0035 Hank Aaron 1976 Milwaukee Brewers trading 0009 1976 Hank Aaron’s Brewers Trading Card card 0010 1998 playoff prestige Randy Moss trading card 0036 19 Chris Chandler Indianapolis Colts Trading 0011 1986 Jerry Rice San Francisco 49ers trading Cards card 0037 Nolan Ryan Mets Trading Card 0012 1998 Peyton Manning Rookie Colts 0038 John Unitas Colts 2000 Reprint 0013 Dave Winfield San Diego Padres trading card 0039 3 Mark McGwire Trading Cards 0014 Troy Aikman Dallas Cowboys 2000 Sno globe 0040 Steve DeLong defensive and San Diego trading Card chargers trading card 0015 Brett Favre Atlanta Falcons Pro Set platinum 0041 John Elway Denver Broncos game day card trading card 0042 Peyton Manning draft picks 1998 0016 Jose Canseco -

Kit Young's Sale #108

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #108 VINTAGE HALL OF FAMERS TREASURE CHEST Here’s a tremendous selection of vintage old Hall of Fame players – one of our largest listings ever. A super opportunity to add vintage Hall of Famers to your collection. Look closely – many hard-to-find names and tougher, seldom offered issues are listed. Players are shown alphabetically. GROVER ALEXANDER 1960 Fleer #45 ................................NR-MT 4.50 1939 R303B Goudey Premium ............EX 395.00 1940 Play Ball #119 ...........................EX $79.95 EDDIE COLLINS 1939-46 Salutation Exhibit ........ SGC 55 VG-EX+ 1948 Hall of Fame Exhibit .............. EX-MT 24.95 LOU BOUDREAU 1914 WG4 Polo Grounds ...............VG-EX $58.95 120.00 1948 Topps Magic Photo ...................... VG 30.00 1939-46 Salutation Exhibit .................EX $12.00 1948 HOF Exhibit ..............................VG-EX 4.95 1952 Berk Ross ....................SGC 84 NM 550.00 1950 Callahan .................................NR-MT 8.00 1949 Bowman #11 .................EX+/EX-MT 55.00 1950 Callahan .................................NR-MT 6.00 1956-63 Artvue Postcard ... EX-MT/NR-MT 57.50 1951 Bowman #62 ...............EX 30.00; VG 20.00 1961 Nu Card Scoops #467 ............... EX+ 29.00 CAP ANSON 1955 Bowman #89 ....... EX-MT 24.00; EX 14.00; JIMMY COLLINS 1950 Callahan .......... NR-MT $6.00; EX-MT 5.00 VG-EX 12.00 1950 Callahan ...............................NR-MT $6.00 BOBBY DOERR 1953-55 Artvue Postcard ............... EX-MT 14.50 1960 Fleer #25 ................................NR-MT 4.95 1948-49 Leaf #83 ..................... EX-MT $150.00 ROGER BRESNAHAN 1961-62 Fleer #99 .......................... EX-MT 8.50 1950 Bowman #43 .........................VG-EX 32.00 LUKE APPLING 1909-11 T206 Portrait ...................... -

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry Artie Zillante University of North Carolina Charlotte November 25th,2007 1Introduction If the attempt by The Upper Deck Company (Upper Deck) to purchase The Topps Company, Inc. (Topps) is successful, the baseball card industry will have come full circle in under 30 years. A legal ruling broke the Topps monopoly in the industry in 1981, but by 2007 the industry had experienced a boom and bust cycle1 that led to the entry and exit of a number of firms, numerous innovations, and changes in competitive practices. If successful, Upper Deck’s purchase of Topps will return the industry to a monopoly. The goal of this piece is to look at how secondary market forces have shaped primary market behavior in two ways. First, in the innovations produced as competition between manufacturers intensified. Second, in the change in how manufacturers competed. Traditional economic analysis assumes competition along one dimension, such as Cournot quantity competition or Bertrand price competition, with little consideration of whether or not the choice of competitive strategy changes. Thus, the focus will be on the suggested retail price (SRP) of cards as well as on the timing of product releases in the industry. Baseballcardshaveundergonedramaticchangesinthepasthalfcenturyastheindustryandthehobby have matured, but the last 20 years have provided a dramatic change in the types of products being produced. Prior to World War II, baseball cards were primarily used as premiums or advertising tools for tobacco and candy products. Information on the use of baseball cards as advertising tools in the tobacco and candy industries prior to World War II can be obtained from a number of different sources, including Kirk (1990) and most of the annual comprehensive baseball card price guides produced by Beckett publishing. -

Era of the Cigarette Card”

In 1945 Esquire Magazine Reported on the “Era of the Cigarette Card” by George G. Vrechek Early articles about the trading card hobby started to appear in a few publications in the mid-1930s. Articles were written by Jefferson Burdick for Hobbies magazine or for his own small publication, The Card Collector’s Bulletin. Hobbies had a significant circulation and published over 100 pages each month, but the Burdick articles were brief and seldom illustrated. A 1929 The New Yorker magazine article, A New York Childhood, Cigarette Pictures, by Arthur H. Folwell, was a rare blip as to mainstream publicity about card collecting. In a January 6, 2006, SCD article I covered Folwell‟s piece which was based on his personal experience in collecting cards during the 1880s. It was a nice bit of nostalgia but didn‟t bring readers up to date as to any 1929 collecting activity. Esquire Magazine December 1945 I had heard of another card article that appeared in Esquire magazine in December 1945. Esquire preceded Playboy as a publication targeting the male audience. Hugh Hefner worked as a copywriter for Esquire before leaving in 1952 to establish Playboy. Esquires from this era contained pin-ups by Alberto Vargas and are collectible because of his artwork. The issue I finally managed to come up with was intact, except for the Vargas girl. There were some marginally naughty cartoons and a few young starlets in two piece swim suits interspersed among 328 pages of articles and ads. Esquire writers included Sinclair Lewis and dozens of other notables including one Karl Baarslag, the author of the cigarette card article of my interest. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #21 Welcome to Kit Young’s Sale #21. Included in this sale are more fantastic sets MAKE US from The Barry Korngiebel Collection (and we have extended the “make us an AN OFFER II offer” option). Also included are outstanding new arrivals, 1/2 price GAI graded For a limited time you can make us an offer cards part II, baseball lot specials part II, a new set special section, Ted Williams on any set below (or any set on specials and much more. You can order by phone, fax, email, regular mail or www.kityoung.com). We will either accept online through Paypal, Google Checkout or credit cards. If you have any questions your offer or counter with a price more acceptable to both of us. or would like to email your order please email us at [email protected]. Our regular business hours are 8-6 Monday-Friday Pacific time. Toll Free 888-548-9686. 1948 BOWMAN FOOTBALL A 1962 TOPPS BASEBALL B COMPLETE SET VG-EX/EX COMPLETE SET EX-MT This 108 card set issued by Bowman consists of mostly Popular wood-grain border set loaded with stars and rookie cards as it was one of the very first football sets ever Hall of Famers. Overall grade is EX-MT (many better and issued. We’ll call this set VG-EX/EX overall with some better some less). Includes Koufax EX-MT, Clemente EX+/EX- (approx. 20 cards EX-MT) and a few worse. Most cards have MT, Mantle PSA 6 EX-MT, Maris EX/EX+, Berra PSA 6 some wear on the corners but still exhibit great eye appeal. -

Byron R. White Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Byron R. White Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Revised 2012 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003003 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm88077264 Prepared by Harry G. Heiss with the assistance of Kathleen Kelly and Robert Vietrogoski Revised and expanded by Harry G. Heiss with the assistance of Jennifer Bridges and John Monagle Collection Summary Title: Byron R. White Papers Span Dates: 1961-1993 ID No.: MSS77264 Creator: White, Byron R., 1917-2002 Size: 183,500 items ; 858 containers ; 361.4 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, United States deputy attorney general, lawyer, naval intelligence officer, Rhodes scholar, and professional football player. Opinion files and related administrative records documenting cases heard during White's tenure on the Supreme Court, including material on cases involving the "Miranda law", abortion, child pornography, freedom of speech, homosexuality, racial bias, and liability of news organizations. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People White, Byron R., 1917-2002. Organizations United States. Supreme Court. Subjects Abortion--United States. Child pornography--United States. Constitutional law--United States.