Incidental Intellectual Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct # ____________ (office use only) circle one Business Name ____________________________________ Phone Number __________________ Store/ Cell / Home Please note this number will be published in the UD Store locator circle one Business Owner / Manager ______________________________ Fax Number _________________________ Business Address: ___________________________________________ e‐mail address _______________________ ___________________________________________ Store website: _______________________ Please note, Upper Deck WILL NOT ship to anywhere other than your Retail address e‐Bay ID: ____________________________ Beckett Store ID: ______________________ 1.) Is your business operated in a Retail/Commercial (non‐residential) setting? ☐Yes ☐No 2.) Do you have more than one location? ☐Yes ☐No 3.) Store Hours Monday ________ If so, please list additional addresses: Tuesday ________ ____________________________________________________________ Wednesday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Thursday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Friday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Saturday _______ Sunday ________ 4.) Please check the category that best describes your business ☐Hobby Store ☐Wholesaler ☐Case Breaker ☐Show vendor ☐Direct Mail/Online ☐Other _________ 5.) Do you wholesale product online to other dealers? ☐ Yes ☐ No. If yes, what percentage of your business is done this way? _________% 6.) Indicate the -

Stock Market Anomalies and Baseball Cards *

Stock Market Anomalies and Baseball Cards * Joseph Engelberg Linh Le Jared Williams‡ August 2, 2017 Abstract: Baseball cards exhibit anomalies that are analogous to those that have been documented in financial markets, namely, momentum, price drift in the direction of past fundamental performance, and IPO underperformance. Momentum profits are higher among active players than retired players, and among newer sets than older sets. Regarding IPO underperformance, we find newly issued rookie cards underperform newly issued cards of veteran players, and that newly issued sets underperform older sets. The results are broadly consistent with models of slow information diffusion and short-selling constraints. * We thank Jack Bao, Justin Birru (discussant), Dan Bradley, Roni Michaely, Matthew Spiegel, and seminar participants at the University of South Florida and the Financial Intermediation Research Society meeting in Hong Kong (2017) for their useful feedback. ‡ Contact: Joseph Engelberg, University of California – San Diego, Rady School of Management, (Email) [email protected] (Tel) 858-822-7912; Linh Le, University of South Florida, Muma College of Business, (Email) [email protected]; and Jared Williams, University of South Florida, Muma College of Business, (Email) [email protected]. 1 I. Introduction Basic financial theory predicts that stock returns should be unpredictable after adjusting for risks. That is, any abnormal returns earned by trading strategies are either due to random chance or they are compensation for risks that investors care about that are not captured by the asset pricing model. However, financial economists have documented the existence of simple strategies that earn unusually high or low returns despite the fact that the strategies do not load heavily on common risk factors. -

May 25 Online Auction

09/28/21 11:47:12 May 25 Online Auction Auction Opens: Thu, May 20 9:00pm ET Auction Closes: Tue, May 25 7:00pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 1 Smoky Mountain Propane Smoker, Works 101 Viagra Pfizer Plastic Wall Clock, Great Gag Great, Racks, Fire Box, Everything Here, Very Gift or Fun Conversation Starter in Your Man Little Wear, Good Condition, 16"W x 15"D x Cave, Very Good Working Condition, 11 1/2" x 45 1/2"H 10 1/4" 10 Combat WWII Box Set Don Congdon 1010 1795 Great Britain 1/2 Penny Paperback With Maps And Commentary WWII Four Books in Set, Very Good Condition 1011 Very Pretty Matching Silvertone Necklace and 100 Heavy Black Metal Bulldog Door Knocker, Pierced Earring Set, All New, Pretty Multi Good Condition, 5"W x 8"H Colored Hearts, 19"L Necklace, 1" Drop 1000 1967 Royal Canadian Mint Silver Proof Set Earrings With 1.1 Oz. of Silver 1012 1883 P Morgan Silver Dollar, AU 55 Cleaned 1001 Goldtone Butterfly Ring Size 9, Painted Enamel 1013 18" Silvertone Necklace With 2" Angel Pendant With CZ Accents, Stamped 925, Very Good Pin, Very Good Condition Condition 1014 1890 CC Morgan Dollar, Rare Key Date, 1002 1904-O Morgan Silver Dollar, MS63 Carson City Mint 1003 2 Piece Silvertone Fire Opal Ring Set, Size 8, 1015 30"L Silvertone Plastic Bead Necklace, Good Blue with Clear Stone, Matched Band, Stamped Condition 925, Very Good Condition 1016 Very Nice 1903 S Key Date Morgan Silver 1004 1881-S Morgan Dollar MS-63 Condition, San Dollar, Only 1,241,000 Minted, Attractive Coin Francisco Mint With Great Patina 1005 Vintage Arion Music Award Ribbon -

Each Hobby Box of 2019 Topps Allen & Ginter Delivers 3

HOBBY EACH HOBBY BOX OF 2019 TOPPS ALLEN & GINTER DELIVERS 3 HITS, INCLUDING ON-CARD AUTOGRAPHS, RELICS, ORIGINAL A&G BUYBACKS, BOOK CARDS, CUT SIGNATURES, AND RIP CARDS! Base Card – Mini Wood Parallel Star Signs Insert Base Card Celebrating the world’s greatest champions and most iconic figures, Topps Allen & Ginter returns in July 2019. BASE CARDS BASE CARDS – Featuring 300 of the top MLB® stars, Rookies and retired greats, as well as non-baseball champions. • Silver Portrait Parallel - GINTER HOT BOX ONLY • Glossy Parallel – Numbered 1-of-1 BASE CARD SHORT PRINTS – 50 subjects not found in the base set. • Silver Portrait Parallel - GINTER HOT BOX ONLY • Glossy Parallel – Numbered 1-of-1 Base Card – Full-Size BASE CARDS MINI CARDS • Base Mini Parallel – 1 per pack • Allen & Ginter Parallel – 1:5 packs • Black Bordered – 1:10 packs • No Number – Limited to 50 • Brooklyn Back – Numbered to 25 • Wood – Numbered 1-of-1 HOBBY ONLY • Glossy – Numbered 1-of-1 MINI CARDS SHORT PRINT • Base Mini Parallel – 1:13 packs • Allen & Ginter Parallel – 1:65 packs • Black Bordered – 1:30 packs • No Number – Limited to 50 • Brooklyn Back – Numbered to 25 • Wood – Numbered 1-of-1 HOBBY ONLY • Glossy – Numbered 1-of-1 MINI SIZED METALS • 150 subjects – limited to 3 HOBBY ONLY Base Card – Mini Base Card Mini Base Card – Black Border Parallel Mini Wood Parallel NEW! MINI STAINED GLASS VARIATIONS • 150 subjects – limited to 25 FRAMED MINI PARALLELS • Printing Plates – Numbered 1-of-1 • Cloth Cards – Numbered to 10 HOBBY ONLY RELIC CARDS & ORIGINALS ALLEN & GINTER FULL-SIZE RELICS – Featuring MLB® Players, world champion athletes, and personalities. -

Hobby History Burdick’S First Catalog of Cards

Hobby History Burdick’s First Catalog of Cards Jefferson Burdick, the Father of Card Collecting (note the 1946 ACC on his desk) By George Vrechek The first catalog arrived 73 years ago and still looks good The 1946, 1953 and 1960 catalogs. Jefferson Burdick (1900-1963) started the first newsletter for card collectors, originated the classification system for cards, and donated his 306,353-card collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Not surprisingly, his first attempt at publishing a catalog for collectable cards was superb. Many readers are familiar with Burdick’s 1960 The American Card Catalog. Burdick was what you would call a regular guy. He published a catalog every seven years and a newsletter every other month without fail. In their uncontrollable urge to collect and organize, modern collectors have made Burdick’s catalogs collectables themselves. Every seven years Burdick published catalogs in 1939, 1946, 1953 (with an updated re-printing in 1956), and 1960. The 1939 catalog was called The United States Card Collectors Catalog; all subsequent catalogs were called The American Card Catalog, Burdick feeling that Canada, Central, and South America should be included in the fold (and potential subscribers). Following Burdick’s death, Woody Gelman continued the catalog one more time with a 1967 effort. Thereafter, catalogs morphed into Bert Sugar’s The Sports Collectors Bible, Beckett & Eckes’s The Sport Americana Baseball Card Price Guide, SCD’s Standard Catalog of Baseball Cards, as well as other publications over the years. Burdick’s catalogs were more plentiful with each successive edition. -

Baseball Cards of the 1950S: a Kid’S View Looking Back by Tom Cotter CBS and NBC All Broadcast Televised Games in the 1950S and On

Like us and Devoted to Antiques, follow us Collectibles, on Furniture, Art and Facebook Design. May 2017 EstaBLIshEd In 1972 Volume 45, number 5 Baseball Cards of the 1950s: A Kid’s View Looking Back By Tom Cotter CBS and NBC all broadcast televised games in the 1950s and on. 1950 saw the first televised All-Star game; 1951 While I am not sure what got us started, about 1955 the premier game in color; 1955 the first World Series in we began collecting baseball cards (my brother was eight, color (NBC); 1958 the beginning televised game from the I was five). I suspect it was reasonably inexpensive and West Coast (L.A. Dodgers at S.F. Giants with Vin Scully we were certainly in love with baseball. We lived in Wi - announcing); and 1959 the number one replay (requested chita, Kansas, which in the 1950s had minor league teams by legend Mel Allen of his producer.) In 1950, all 16 (Milwaukee Braves AAA affiliate 1956-1958), although I Major League teams were from St. Louis to the East Coast don’t recall that we went to any games. However, being and mostly trains were used for travel. The National somewhat competitive and playing baseball all summer, League contained: Boston Braves, New York Giants, we each chose a team to root for and rather built our base - Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburg Pirates, ball card collections around those teams. My brother’s Cincinnati Redlegs (1953-1960 no “Reds” during the Mc - favorite team was the Chicago Cubs, with perennial All- Carthy Era), Chicago Cubs, and St. -

Honus Wagner 1909-11 T206 Card and His Personal Safe To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Terry Melia – 949-831-3700, [email protected] HONUS WAGNER 1909-11 T206 CARD AND HIS PERSONAL SAFE TO BE AUCTIONED AS PART OF SCP AUCTIONS’ ‘FALL PREMIER’ Auction of Wagner’s T206 Card and Safe Winds Down Saturday, Dec. 6 Laguna Niguel, Calif. (Dec. 3, 2014) – SCP Auctions’ “Fall Premier” online auction ends this Saturday, Dec. 6, at www.scpauctions.com. It features more than 1,150 lots including the coveted Chesapeake Honus Wagner 1909-11 T206 card and a small but highly significant group of Jackie Robinson related memorabilia including his spectacular Hillerich & Bradsby Model S100 ash bat, one of only two Robinson game-used bats that can be definitively documented as having been used during his 1949 MVP season. Also included is Wagner’s personal safe which was part of Wagner's estate collection received directly from the Wagner family's home in Carnegie, Pa. and sold by SCP Auctions in 2003 on behalf of Leslie Blair Wagner (Honus’s granddaughter). Can you imagine a more ideal place to store your prized T206 Honus Wagner card? For decades, Honus Wagner himself stored some his most important possessions in this floor safe. The safe, manufactured specially for Wagner by the F.L. Norton Safe Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa., dates from the turn-of-the-century. Its dimensions are 25" high by 16"wide by 17"deep and weighs about 250 pounds. Wagner's name "J.H. Wagner" is stenciled across to top in gold paint. A decorative border is stenciled around the perimeter of the door, which also bears the manufacturers markings below the dial. -

The Timeless Collaboration of Artwork and Sports Cards

op Ink& PAPER The timeless collaboration of artwork and sports cards BY DAVID LEE ports cards, like paintings, have no intrinsic value. Both are simply ink on paper. But as novelist Jerzy Kosiński wrote, “The prin- ciples of true art is not to portray, but to evoke.” SThe same can be said about sports cards. Like art, the value is not in what they’re made of. It’s in what they evoke. It’s how they make you feel. Art and cards are timeless. Both are creative expressions. They mark history and conjure memories. They tell stories and mold culture. To appreciate them requires imagination. Maybe that’s why they have collaborated so naturally for more than a century. From the colorized images on the early 1900s tobacco cards to the widely popular Topps Project 2020 today, sometimes art and sports cards are one in the same. op — 32 ART OF THE GAME — — ART OF THE GAME 33 — Ink& PAPER Launching the Modern Baseball Card op The evolution of baseball cards took a huge leap forward in the early 1950s as Topps and Bowman battled for dominance in the industry. Led by visionary executive Sy Berger, who is referred to as “the father of the modern baseball card,” Topps brought unique size, designs, player stats, and overall beautiful eye appeal to post-World War II baseball cards. Following the groundbreaking 1952 Topps set, the 1953 release derived its images from miniature oil paintings. The result is the most iconic uniting of artwork and sports cards ever produced. “I designed that 1953 card and was instrumental in getting the painting done,” Berger once told Sports Collectors Digest. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

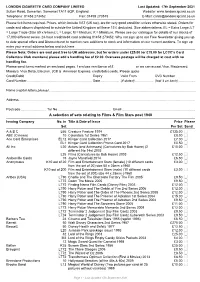

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

Hugginsscottauction Feb13.Pdf

elcome to Huggins and Scott Auctions, the Nation's fastest grow- W ing Sports & Americana Auction House. With this catalog, we are presenting another extensive list of sports cards and memo- rabilia, plus an array of historically significant Americana items. We hope you enjoy this. V E RY IMPORTA N T: DUE TO SIZE CONSTRAINTS AND T H E COST FAC TOR IN THE PRINT VERSION OF MOST CATA LOGS, WE ARE UNABLE TO INCLUDE ALL PICTURES AND ELA B O- R ATE DESCRIPTIONS ON EV E RY SINGLE LOT IN THE AUCTION. HOW EVER, OUR WEBSITE HAS NO LIMITATIONS, SO W E H AVE ADDED MANY MORE PH OTOS AND A MUCH MORE ELA B O R ATE DESCRIPTION ON V I RT UA L LY EV E RY ITEM ON OUR WEBSITE. WELL WO RTH CHECKING OUT IF YOU ARE SERIOUS ABOUT A LOT ! WEBSITE: W W W. H U G G I N S A N D S C OTT. C O M Here's how we are running our February 7, 2013 to STEP 2. A way to check if your bid was accepted is to go auction: to “My Bid List”. If the item you bid on is listed there, you are in. You can now sort your bid list by which lots you BIDDING BEGINS: hold the current high bid for, and which lots you have been Monday Ja n u a ry 28, 2013 at 12:00pm Eastern Ti m e outbid on. IF YOU HAVE NOT PLACED A BID ON AN ITEM BEFORE 10:00 pm EST (on the night the Our auction was designed years ago and still remains geared item ends), YOU CANNOT BID ON THAT ITEM toward affordable vintage items for the serious collector. -

July 2011 Prices Realized

HUGGINS & SCOTT JULY 28, 2011 PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE 1 1968 Topps 3-D Near Set of (10/12) PSA Graded Cards with Perez & Stottlemyre 33 $16,450.00 2 1968 Topps 3-D Roberto Clemente PSA 5 25 $8,225.00 3 1968 Topps 3-D Ron Fairly (No Dugout) Variation PSA 7 8 $763.75 4 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Maloney (No Dugout) Variation PSA 6 3 $528.75 5 1968 Topps 3-D Willie Davis PSA 6 8 $381.88 6 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Lonborg PSA 8 24 $1,410.00 7 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Maloney PSA 8 12 $499.38 8 1968 Topps 3-D Tony Perez PSA 8 33 $3,525.00 9 1968 Topps 3-D Boog Powell PSA 8 30 $2,820.00 10 1968 Topps 3-D Ron Swoboda PSA 7 27 $1,997.50 11 1909-11 T206 Walter Johnson Portrait PSA EX 5 14 $1,410.00 12 (4) 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb Pose Variations-All PSA Graded 28 $3,818.75 13 (4) 1909-11 T206 Graded Hall of Famers & Stars with Lajoie & Mathewson 18 $940.00 14 (10) 1909-11 T206 White Border Graded Cards—All SGC 50-60 11 $528.75 15 (42) T205 Gold Borders & T206 White Borders with (17) Graded & (7) Hall of Famers/Southern Leaguers 21 $1,762.50 16 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folders Egan/Mitchell PSA 7 4 $470.00 17 (37) 1919-21 W514 SGC Graded Collection with Ruth, Hornsby & Johnson--All Authentic 7 $1,292.50 18 (4) 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards—All PSA or SGC 4 $558.13 19 (12) 1917 Collins-McCarthy SGC Graded Singles 12 $499.38 20 (7) 1934-36 Diamond Stars Semi-High Numbers—All SGC 60-80 6 $293.75 21 (18) 1934-36 Batter-Up High Numbers with (6) Hall of Famers—All SGC 60-80 12 $1,410.00 22 (5) 1940-1949 Play Ball, Bowman & Leaf Baseball Hall of