D'auria on Meltzer, 'In the Days of the Pharaohs: a Look at Ancient Egypt'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Work of the Theban Mapping Project by Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021

Virtual Lecture Transcript: Does the Past Have a Future? The Work of the Theban Mapping Project By Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021 David A. Anderson: Well, hello, everyone, and welcome to the third of our January public lecture series. I'm Dr. David Anderson, the vice president of the board of governors of ARCE, and I want to welcome you to a very special lecture today with Dr. Kent Weeks titled, Does the Past Have a Future: The Work of the Theban Mapping Project. This lecture is celebrating the work of the Theban Mapping Project as well as the launch of the new Theban Mapping Project website, www.thebanmappingproject.com. Before we introduce Dr. Weeks, for those of you who are new to ARCE, we are a private nonprofit organization whose mission is to support the research on all aspects of Egyptian history and culture, foster a broader knowledge about Egypt among the general public and to support American- Egyptian cultural ties. As a nonprofit, we rely on ARCE members to support our work, so I want to first give a special welcome to our ARCE members who are joining us today. If you are not already a member and are interested in becoming one, I invite you to visit our website arce.org and join online to learn more about the organization and the important work that all of our members are doing. We provide a suite of benefits to our members including private members-only lecture series. Our next members-only lecture is on February 6th at 1 p.m. -

The Future of Egypt's Past: Protecting Ancient Thebes

The Oregon Archaeological Society and the Oregon Chapter, American Research Center in Egypt present OREGON CHAPTER THE FUTURE OF EGYPT’S PAST: PROTECTING ANCIENT THEBES By Dr Kent R Weeks, Director, The Theban Mapping Project In 1978, the Theban Mapping Project (TMP) was an ambitious plan to record, photograph and map every temple and tomb in the Theban Necropolis (modern Luxor, Egypt) within a few years. However, it took nearly two decades before the enormous task was realized and the Atlas of the Valley of the Kings was published. Dr Weeks has guided the TMP on a sometimes surprising journey. In 1995, an effort to pinpoint where early explorers had noted an “insignificant” tomb led to the re-discovery of KV5. Recognized now as the tomb for sons of Ramesses II, it is the most important find since the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb. Once primarily aimed at treasure, gold, jewels and mummies, today archaeology in the Valley of the Kings targets information, accessibility and protection. The TMP remains relevant, developing an online Egyptian Archaeological Database, a newly upgraded TMP website, and a program of local public education to encourage archaeological awareness, site conservation and site management, as well as continuing work in KV5. Tuesday, May 7, 2019 at 7:30 Empirical Theater at Oregon Museum of Science & Industry 1945 SE Water Ave., Portland Free admission, free parking and open to the public. DR KENT WEEKS has directed the Theban Mapping Project since its inception in 1978. Born in Everett and having grown up in Longview, Washington, he obtained his master’s degree at U of Washington and later, a doctorate from Yale. -

Build Me a Pyramid �Ating �Ac� to A�Out ���� ����� �Oun�S An� �Ac�Als Is a Have You Ever Wondered What Might Lie Between Its Front Paws Is a Partial Inscription

Week 7 of 28 • Page 4 WEEK 7 Name _________________________ Pyramids ACROSS 2. the northern end of the Suez Canal 7. rst eale pharaoh o ancient gpt 8. lae create uiling the san igh a DOWN 1. this once covere the prais 3. pharaoh with about 100 children 4. oun ing uts o 5. statue with the body of a lion and the head of a man 6. found the Tomb of the Sons of Ramses II 9. the southern end of the Suez Canal s ou rea this ees lesson circle or highlight all proper nouns ith an color pen or highlighter his ill help ou n soe o the crossor ansers an get rea or this ees test Hounds and Jackals Build Me a Pyramid ating ac to aout ouns an acals is a Have you ever wondered what might lie Between its front paws is a partial inscription. moved them to the site, since they didn’t have oar gae that has een oun in several gptian tos beneath the desert sands of Egypt? Over time, It tells the story of a young prince who fell asleep the machines we have today. Archaeologists t is soeties calle he ae o oles lthough no the sand has been slowly giving up some of its by the giant sphinx. In his dream, the sphinx believe workers (not slaves) hauled the stone irections have een oun it appears to e siilar to hutes an secrets. Thanks to scholars like Jean-Francois told him that if he cleared away the sand from up dirt ramps on wooden sleds with runners. -

EGYPT REVEALED a Symposium on Archaeological Finds from Egypt to Be Held October 13-14, Will Provide a Rare Opportunity to Learn About the Most Recent Discoveries

EGYPT REVEALED A Symposium on Archaeological Finds from Egypt To Be Held October 13-14, Will Provide a Rare Opportunity to Learn about the Most Recent Discoveries TWO-DAY symposium on history of Thebes, its major A the latest archaeological monuments, and the work of finds from Egypt will be held the Theban Mapping Project October 13-14, 2001 in Kane in protecting and preserving Hall, University of Washington. this World Heritage site from The symposium will bring to imminent destruction. campus four prominent Dr. Silverman will report Egyptologists: Mark Lehner, on the expedition at Saqqara Director of the Giza Plateau where the tombs of priests who Mapping Project; Kent Weeks, served the pharaohs are located. Director of the Theban Mapping Dr. Ikram will discuss ancient Project; David Silverman, caravan routes and mum- Curator, Egyptian Section, mification discoveries made University of Pennsylvania this season. Museum of Archaeology and With modern technology Anthropology;and Salima Ikram, changing the face of Assistant Professor of Egyptology, archaeology and Egyptology American University in Cairo, advances are being made using who will present their latest field state-of-the-art computer season reports and analysis of graphics, remote sensing The Pharaoh Tutmosis their most important work. technology, geo-chronologists, Dr. Lehner will report on the paleo-botanists, faunal specialists results of his Millennium Project, and more. The Symposium will questions and to provide useful a two-year intensive survey and demonstrate how far this curriculum material. excavation revealing a vast royal technology has brought us and This symposium is being held complex very modern in its urban where it will lead in the future. -

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Yao Zong (Andy) Ng All rights reserved ABSTRACT Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng The essence of metabolic engineering is the modification of microbes for the overproduction of useful compounds. These cellular factories are increasingly recognized as an environmentally-friendly and cost-effective way to convert inexpensive and renewable feedstocks into products, compared to traditional chemical synthesis from petrochemicals. The products span the spectrum of specialty, fine or bulk chemicals, with uses such as pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, flavors and fragrances, agrochemicals, biofuels and building blocks for other compounds. However, the process of metabolic engineering can be long and expensive, primarily due to technological hurdles, our incomplete understanding of biology, as well as redundancies and limitations built into the natural program of living cells. Combinatorial or directed evolution approaches can enable us to make progress even without a full understanding of the cell, and can also lead to the discovery of new knowledge. This thesis is focused on addressing the technological bottlenecks in the directed evolution cycle, specifically de novo DNA assembly to generate strain libraries and small molecule product screens and selections. In Chapter 1, we begin by examining the origins of the field of metabolic engineering. We review the classic “design–build–test–analyze” (DBTA) metabolic engineering cycle and the different strategies that have been employed to engineer cell metabolism, namely constructive and inverse metabolic engineering. -

International Kv7 Channels Symposium 2019

ABSTRACT BOOK International Kv7 Channels Symposium 2019 INTERNATIONAL Kv7 CHANNELS SYMPOSIUM 12 - 14 September 2019 Naples · Italy www.kv7channels2019naples.org WELCOME Index Oral Abstracts . 21 Poster Abstracts . 71 INFORMATION PROGRAMME INDUSTRY ABSTRACTS 3 WELCOME INFORMATION 21 PROGRAMME Oral Abstracts Oral INDUSTRY ABSTRACTS KEYNOTE SPEAKER [O1] NEURONAL KV7 M-CHANNELS: PROPERTIES AND REGULATION David Brown1 1University College London, Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology, London, United Kingdom I joined the band of future Kv7 afficionados 40 years ago, when we discovered the M-current in bullfrog sympathetic neurons (Brown & Adams, 1979: Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 5:585; 1980:Nature, 283;673). This was seen as a voltage-de- pendent, subthreshold, non-inactivating potassium current that had a dramatic braking action on repetitive action potential discharges. It was dubbed “M-current” because it was inhibited by muscarine, acting on muscarinic ace- tylcholine receptors (mAChRs), thereby increasing action potential discharges. M-current is an imperfect descriptor because the current can also be inhibited by activating other Gq-type G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and mus- carine itself only works if the cell has M1, M3 or M5 receptors, not M2 or M4 (Robbins et al., 1991: Eur J Neurosci. 3: 820). The molecular composition of the M-channel was revealed some two decades later by David McKinnon and his colleagues as a combination of theKCNQ2 and KCNQ3 gene products Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 (Wang et al., 1998: Science. 282: 1890), probably as a 2+2 heteromer (Hadley et al, 2003: J Neurosci. 23: 5012). Though gated by voltage, the channels require the membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to open (Zhanget al., 2003: Neuron. -

Egyptology SB 113.Qxd

EGYPTOLOGY 1 Sakharah, Abydos, Dendera, Kom, Edfu, Phylae, and others—and also on contemporary scenes: the harbor at Danabieh, cataracts at Aswan, dervishes and belly dancers and others (some in studio por- traits), the camel market at Bedrechem, dhows on the Nile, as well as on Cairene mosques and other edifices. Most of the photographs are credited and captioned in the image, to Edit. Schroeder & Cie., Zürich (42 prints), to Art. G. Lekegian & Cie. (34 prints) or Zangaki (10); 4 are not credited. Fine condition. Egypt, n.d. $4,500.00 5 ALDRED, CYRIL. Akhenaten and Nefertiti. 231, (1)pp. 184 illus. (9 color). 47 figs. Sq. 4to. Wraps. Published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. New York (Viking), 1973. $50.00 Arntzen/Rainwater I37 6 ALDRED, CYRIL. Jewels of the Pharaohs. Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period. Abridged. 128pp. 173 illus (109 color). 4to. Cloth. D.j. New York (Ballantine Books), 1978. $35.00 Cf. Arntzen/Rainwater P594 7 ALDRED, CYRIL. Tutankhamun’s Egypt. 90, (6)pp. 8 color plates, 80 illus. Sm. 4to. Wraps. London (British Broadcasting Corporation), 1972. $25.00 8 ALDRED, CYRIL, ET AL. Ancient Egypt in the Metropolitan Museum Journal, Volumes 1-11 (1968-1976). Articles by Cyril Aldred, Henry G. Fischer, Herman de Meulenaere, Birgit Nolte, Edna R. Russmann. 201, (1)pp. Text figs. Lrg. 4to. Cloth. D.j. New York (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), 1977. $75.00 9 ALLAM, SCHAFIK. Das Verfahrensrecht in der altägyptis- chen Arbeitersiedlung von Deir el-Medineh. (Untersuchungen zum Rechtsleben im Alten Ägypten. 1.) 109pp. -

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES in the ARCHAEOLOGY

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies This study considers the physical evidence for tomb robbery on the Theban west bank, and its resultant effects, during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. Each tomb and deposit known from the Valley of the Kings is examined in detail, with the aims of establishing the archaeological context of each find and, wherever possible, isolating and comparing the evidence for post-interment activity. The archaeological and documentary evidence pertaining to the royal caches from Deir el-Bahri, the tomb of Amenophis II and elsewhere is drawn together, and from an analysis of this material it is possible to suggest the routes by which the mummies arrived at their final destinations. Large-scale tomb robbery is shown to have been a relatively uncommon phenomenon, confined to periods of political and economic instability. The caching of the royal mummies may be seen as a direct consequence of the tomb robberies of the late New Kingdom and the subsequent abandonment of the necropolis by Ramesses XI. Associated with the evacuation of the Valley tombs may be discerned an official dismantling of the burials and a re-absorption into the economy of the precious commodities there interred. STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies (Volumes I—II) Volume I: Text by Carl Nicholas Reeves Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental Studies University of Durham 1984 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Nile Magazine No. 6 (2017)

NILEMAGAZINE.CO.UK | #6 | FEBRUARY / MARCH 2017 £4.90 NILENILE~ DiscoverDiscover AncientAncient EgyptEgypt TodayToday WIN CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLES by Bob Brier Part 2 : Queens OF THE NILE How to read TOMB SYMBOLS Top 5 Discoveries OF 2016 THE HAREM CONSPIRACY Join us on this exciting new tour designed to look at THE some of the fascinating sites discussed in Chris Naunton’s MISSING new book to be published this Autumn. TOMBS with Dr Chris Naunton th DEPARTING 29 OCTOBER 2017 We begin in Cairo with visits to the Giza Plateau, Saqqara and Tanis, the Delta’s most impressive site. We journey to Alexandria to explore this historic city on the Mediterranean Coast. A highlight is the special AWT permit to visit Taposiris Magna, believed to be the burial site of Cleopatra and where excavations are still underway. We travel through Middle Egypt, viewing the colourful tombs at Beni Hassan, the city of Akhenaten and Nefertiti at Tel el Amarna and the remote tombs at Meir. On to Abydos where we see the most wonderful reliefs in Egypt on the walls of Seti I Temple. A fi rst for AWT, we include a private permit to enter the re-excavated Tomb of Senusret III at Abydos. Senusret’s tomb set at the edge of the desert in ‘Anubis Mountain’ is one of the largest royal tombs ever built in Ancient Egypt. The Penn Museum team are still excavating in the area. On arrival in Luxor we have arranged visits relevant to our tour theme, these include The Kings’ Valley, the West Valley, Deir el Medina, the Ramesseum, Medinet Habu and Hatshepsut’s Temple. -

The Last of the Experimental Royal Tombs in the Valley of the Kings: KV42 and KV34 Sjef Willockx

The last of the experimental royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings: KV42 and KV34 by Sjef Willockx The last of the experimental royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings: KV42 and KV34 © Sjef Willockx, 2011 . Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ 3 List of Tables ................................................................................................................. 4 Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 1. The earliest development of the necropolis in the Valley of the Kings ...................... 11 2. KV42 ....................................................................................................................... 16 2.1. Carter ............................................................................................................ 16 2.2. Weigall .......................................................................................................... 20 2.3. Carter again: the foundation deposits of Hatshepsut-Meryetre ...................... 20 2.4. Hayes ............................................................................................................ 23 2.4.1. The tomb .................................................................................................... 23 -

A Re-Examination of O. Cairo Jde 72460 (= O

A RE-EXAMINATION OF O. CAIRO JDE 72460 (= O. CAIRO SR 1475) Ending the quest for a 19th Dynasty queen’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings Andreas DORN & Stéphane POLIS (Université de Liège & F.R.S.-FNRS) Résumé. Dans cette contribution, nous procédons à un nouvel examen de l’O. Caire JdE 72460 : après avoir discuté les interpré- tations possibles pour ce texte, en nous appuyant sur une analyse des expressions de mesure de distance dans les textes du Nouvel Empire, nous examinons les correspondances qui peuvent être établies entre les emplacements et distances mentionnées dans l’ostracon, d’une part, et les structures archéologiques conservées dans la Nécropole thébaine, d’autre part. Nous arrivons à la conclu- sion que ce document pourrait bien se rapporter à des travaux en cours à l’intérieur de KV 5. Abstract. In this paper, we offer a new interpretation for O. Cairo JdE 72460. Based on a discussion of the expressions used for measuring distances in the New Kingdom documentation, we explore the various possible translations. We then try to map the abstract relationships between places as well as the related measurements onto actual archeological structures. We come to the conclusion that this ostracon might be linked to work in progress inside KV 5. 0. INTRODUCTION The famous O. JdE 72460 — which mentions distances between several places in the Theban necropolis, including the building sites of tombs — was first published by E. Thomas in 19761, based on an earlier tran- scription made by J. Černý. Some years ago, this document received a thorough commentary by K.C. -

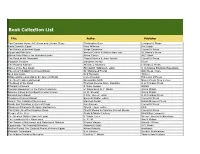

Book Collection List

Book Collection List Title Author Publisher The Cannibal Hymn: A Cultural and Literary Study Christopher Eyre Liverpool U Press Early Dynastic Egypt Toby Wilkison Routledge The Priests of Ancient Egypt Serge Sauneron Cornell U Press Egypt and Palestine Amnon Cohen & Gabriel Baer eds. St. Martin's Press Bibical Holy Places: an illustrated guide Rivka Gonen A&C Black The Book of the Pharoahs Pascal Vernus & Jean Yoyette Cornell U Press Egyptian Temples Margaret Murray Dover The Road to Kadesh William J. Murnane Chicago U Press Valley of the Sun Kings Richard H. Wilkinson, editor U of Arizona Egyptian Expedition The Art of Childbirth in Ancient Egypt Dr. Mohamed Fayad Star Press, Cairo Idea into Image Erik Hornung Timken Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World Lionel Casson Princeton U Press The Sea Peoples and Egypt Alessandra Nibbi Noyes Press, New Jersey The Book of the Dead Thomas George Allen, translator U of Chicago Press Pharaoh's Flowers F. Nigel Hepper HMSO Canopic Equipment in the Petrie Collection V. Raisman & G. T. Martin Aris & Philips Mummy Cases & Inscribed Funerary Cones H. M. Stewart Aris & Philips Excavating in Egypt T.G.H. James, editor U of Chicago Press Temples of Ancient Egypt Byron E.Shafer, editor Cornell U Press Avaris: The Capital of the Hyksos Manfied Bietak British Museum Press Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt Jan Assman Cornell U Press Studies in Pharaonic Religion and Society Alan B. Lloyd, editor EES The Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods Dimitri Meeks & Christine Favard-Meeks Cornell U Press People of the Sea Trudy & Moshe Dothan MacMillan Company The Medical Skills of Ancient Egypt J.