The Epic of Gilgamesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

Mesopotamian Epic."

' / Prof. Scott B. Noege1 Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington "Mesopotamian Epic." First Published in: John Miles Foley, ed. The Blackwell Companion to Ancient Epic London: Blackwell (2005), 233-245. ' / \.-/ A COMPANION TO ANCIENT EPIC Edited by John Miles Foley ~ A Blackwell '-II Publishing ~"o< - -_u - - ------ @ 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right ofJohn Miles Foley to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2005 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to ancient epic / edited by John Miles Foley. p. cm. - (Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Literature and culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4051-0524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Epic poetry-History and criticism. 2. Epic literature-History and criticism. 3. Epic poetry, Classical-History and criticism. I. Foley, John Miles. II. Series. PN1317.C662005 809.1'32-dc22 2004018322 ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-0524-8 (hardback) A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh 47 The Epic of Gilgamesh Perhaps arranged in the fifteenth century B.C., The Epic of Gilgamesh draws on even more ancient traditions of a Sumerian king who ruled a great city in what is now southern Iraq around 2800 B.C. This poem (more lyric than epic, in fact) is the earliest extant monument of great literature, presenting archetypal themes of friendship, renown, and facing up to mortality, and it may well have exercised influence on both Genesis and the Homeric epics. 49 Prologue He had seen everything, had experienced all emotions, from ex- altation to despair, had been granted a vision into the great mystery, the secret places, the primeval days before the Flood. He had jour- neyed to the edge of the world and made his way back, exhausted but whole. He had carved his trials on stone tablets, had restored the holy Eanna Temple and the massive wall of Uruk, which no city on earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares. Find the cornerstone and under it the copper box that is marked with his name. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

COREComp. by: PG0963 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 9780521880947c01 Date:29/ Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk 11/09 Time:13:00:38 Filepath:H:/01_CUP/3B2/Bates-9780521880947/ ProvidedApplications/3B2/Proof/9780521880947c01.3d by SOAS Research Online 1 A. R. GEORGE The Epic of Gilgamesh Introduction The name ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ is given to the Babylonian poem that tells the deeds of Gilgamesh, the greatest king and mightiest hero of ancient Mesopotamian legend. The poem falls into the category ‘epic’ because it is a long narrative poem of heroic content and has the seriousness and pathos that have sometimes been identified as markers of epic. Some early Assyri- ologists, when nationalism was a potent political force, characterized it as the ‘national epic’ of Babylonia, but this notion has deservedly lapsed. The poem’s subject is not the establishment of a Babylonian nation nor an episode in that nation’s history, but the vain quest of a man to escape his mortality. In its final and best-preserved version it is a sombre meditation on the human condition. The glorious exploits it tells are motivated by individ- ual human predicaments, especially desire for fame and horror of death. The emotional struggles related in the story of Gilgamesh are those of no collective group but of the individual. Among its timeless themes are the friction between nature and civilization, friendship between men, the place in the universe of gods, kings and mortals, and the misuse of power. The poem speaks to the anxieties and life-experience of a human being, and that is why modern readers find it both profound and enduringly relevant. -

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh- King of Uruk, the Strongest of Men, and the Perfect Example of All Human Virtues. a Brave

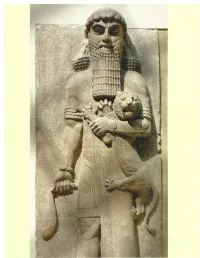

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh - King of Uruk, the strongest of men, and the perfect example of all human virtues. A brave warrior, fair judge, and ambitious builder, Gilgamesh surrounds the city of Uruk with magnificent walls and erects its glorious ziggurats, or temple towers. Two-thirds god and one-third mortal, Gilgamesh is undone by grief when his beloved companion Enkidu dies, and by despair at the fear of his own extinction. He travels to the ends of the Earth in search of answers to the mysteries of life and death. Enkidu - Companion and friend of Gilgamesh. Hairy-bodied and muscular, Enkidu was raised by animals. Even after he joins the civilized world, he retains many of his undomesticated characteristics. Enkidu looks much like Gilgamesh and is almost his physical equal. He aspires to be Gilgamesh’s rival but instead becomes his soul mate. The gods punish Gilgamesh and Enkidu by giving Enkidu a slow, painful, inglorious death for killing the demon Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Aruru - A goddess of creation who fashioned Enkidu from clay and her saliva. Humbaba - The fearsome demon who guards the Cedar Forest forbidden to mortals. Humbaba’s seven garments produce a feeling that paralyzes fear in anyone who would defy or confront him. He is the prime example of awesome natural power and danger. His mouth is fire, he roars like a flood, and he breathes death, much like an erupting volcano. In his very last moments he acquires personality and pathos, when he pleads cunningly for his life. Siduri - The goddess of wine-making and brewing. -

Atra-Hasis: a Survey

Grace Theological Journal 12.2 (Spring, 1971) 3-22 Copyright © 1971 by Grace Theological Seminary. Cited with permission from ATRA-HASIS: A SURVEY JAMES R. BATTENFIELD Teaching Fellow in Hebrew Grace Theological Seminary New discoveries continue to revive interest in the study of the ancient Near East. The recent collation and publication of the Atra-hasis Epic is a very significant example of the vigor of this field, especially as the ancient Near East is brought into comparison with the Old Testa- ment. The epic is a literary form of Sumero-Babylonian traditions about the creation and early history of man, and the Flood. It is a story that not only bears upon the famous Gilgamesh Epic, but also needs to be compared to the narrative of the Genesis Flood in the Old Testament. The implications inherent in the study of such an epic as Atra-hasis must certainly impinge on scholars' understanding of earth origins and geology. The advance in research that has been conducted relative to Atra- hasis is graphically apparent when one examines the (ca. 1955) rendering by Speiser1 in comparison with the present volume by Lambert and Millard.2 Although Atra-hasis deals with both creation and flood, the pre- sent writer has set out to give his attention to the flood material only. Literature on mythological genres is voluminous. Therefore the present writer will limit this study to a survey of the source material which underlies Atra-hasis, a discussion of its content and its relation to the Old Testament and the Gilgamesh Epic. James R. -

Mesopotamian Society Was a Man the TRANSITION Named Gilgamesh

y far, the most familiar individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man THE TRANSITION named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth TO AGRICULTURE king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C. E., and he led his community The Paleolithic Era in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. The Neolithic Era Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as his tory. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards THE QUEST FOR ORDER made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as the Epic of Mesopotamia: "The Land Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of between the Rivers" ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a per The Course of Empire fect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. The legends declare that he constructed the massive city walls of Uruk as well as several of the THE FORMATION OF A COMPLEX SOCIETY city's magnificent temples to Mesopotamian deities. AND SOPHISTICATED The stories that make up the Epic of Gi/gamesh recount the adventures of this CULTURAL TRADITIONS hero and his cherished friend Enkidu as they sought fame. They killed an evil mon Economic Specialization ster, rescued Uruk from a ravaging bull, and matched wits with the gods. In spite of and Trade their heroic deeds, Enkidu offended the gods and fell under a sentence of death. The Emergence of a His loss profoundly affected Gilgamesh, who sought The Epic of Gilgamesh Stratified Patriarchal Society for some means to cheat death and gain eternal www.mhhe.com/ • bentleybrief2e The Development of Written life. -

Suffering in the Epic of Gilgamesh*

690 De Villiers, “Suffering in Gilgamesh,” OTE 33/3 (2020): 690-705 Suffering in the Epic of Gilgamesh* GERDA DE VILLIERS (UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA) ABSTRACT This article examines moments of suffering in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Initially Gilgamesh himself causes much suffering by abusing his power as king and tormenting his subjects day and night. Enkidu is created to curb the king’s energy and to alleviate the distress of the people. Gilgamesh’s greatest joy in finding a true friend also turns into his greatest sorrow when Enkidu becomes ill and dies. Gilgamesh is inconsolable and his suffering drives him away from his palace and his city, in search of life everlasting. When a snake snatches away his last hope of living forever, he realises that life eternal is to be found in life here and now. The article concludes with some suggestions of appropriating Elizabeth Kubler Ross’ five stages of grief to the Epic of Gilgamesh. KEYWORDS: Gilgamesh, Enkidu, Uruk, Suffering, Trauma, Grief, Death A INTRODUCTION During the recent three decades or so, the Epic of Gilgamesh has attracted the attention of several scholars for various reasons. Works from the ancient Greek and Roman world, like those of Homer, Hesiod and Virgil, were known for many ages and they inspired especially the artists of the Renaissance period. However, not much, if any knowledge existed about ancient Mesopotamia and the great civilizations of Babylon and Assyria, except for the rather negative portrayal of these cultures in the Hebrew Bible. Interest in the Gilgamesh Epic was sparked only in 1872 when George Smith, a brilliant amateur Assyriologist deciphered Tablet XI of the Epic, whilst working in the British Museum.1 To his astonishment Smith realised that what he was reading, was in fact the so-called Babylonian Flood narrative, which has remarkable resemblances with but also shows significant differences from the biblical account of the Deluge (Gen 9– 11). -

Enuma Elish Epic

¿?A^o c.«*- ' The Epic of Creation: Introduction 229 surprising lack of textual variation is to be found in the tablets, which came from a variety of sites and periods. This may be The Epic of Creation explained either as indicating that composition is relatively late, and that there is no oral background; or as showing that a text became 'canonized' if it was used for a particular ritual, as this epic was. When Sennacherib described scenes from the epic with The E pic of Creation is named an epic in a sense quite different to which he decorated the doors of the Temple of the New Year that of theEpic of Gilgamesh. Here is no struggle against fate, Festival, he included details which are not found in the extant no mortal heroes, no sense of suspense over the outcome of version, such as that the god Amurru was Assur's charioteer, events. The success of the hero-god Marduk (in the Babylonian and so we may deduce that there were indeed different versions version, Assur in the Assyrian version) is a foregone conclusion. in circulation. None of the good gods is injured or killed; no tears are shed. Yet If it is correct that the version with Marduk is the original one, cosmic events are narrated: the earliest generations of gods are the epic cannot have been composed before the reign of Sumu- recounted leading up to the birth of the latest hero-god; the la-el (1936-1901 вс), an Amorite ruler under whom Babylon, forces of evil and chaos are overcome, whereupon the present with Marduk as its patron god, first achieved eminence. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh: a Saga of Humanism Mythified

The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Saga of Humanism Mythified Ajay Kumar Gangopadhyay Associate Professor Department of English J.K. College, Purulia “Gilgamesh is stupendous”, - said Rainer Maria Rilke, after he read the translation of the epic made by the German Assyriologist Arthur Ungnad. Rilke observed that Gilgamesh was “das Epos der Todesfurcht” – “the epic about the fear of death”. Written in Cuneiform script in hundreds of tablets discovered from various places of ancient Mesopotemia, ostensibly by several hands through the centuries, Gilgamesh is the story of the eponymous hero who was the king of Uruk, a province of ancient Mesopotemia by the river Ufrates. This earliest effort to compose a great saga of human virility and quest for immortality, was started, as evidences certify, during 2600 B.C., though the systematic epical efforts started probably from 2100 B.C. The epic was discovered by modern Assyriologists Austen Henry Layard, Hormuzd Rassam and W.K. Loftus in 1853 from the ruins of the library in Nineveh of the 7th century B.C. Assyririan king Ashurbanipal. George Smith was the first modern translator of this epicwho made it during the 1970s, though the first Arabian translation by Taha Bariq was done in 1960s. This sumptuous saga has been translated in no less than sixteen languages, and the original story is scattered in more than eighty manuscripts retrieved from various places. The clay tablets have been found mainly in the ancient cities of Mesopotemia, the Levant and Anatolia, the sites in modern Iraq. The Cuneiform writing was invented in the city-states of lower Mesopotemia in about 3000 B.C. -

REL 101 Lecture 17 1 Hello Again. Welcome Back to Class. This Is Religious Studies 101, Literature and World of the Hebrew Bible

REL 101 Lecture 17 1 Hello again. Welcome back to class. This is Religious Studies 101, Literature and World of the Hebrew Bible. My name is John Strong. This is session 17 and today we’re gonna be looking at ancient Near Eastern parallel literature. Specifically, we’re gonna be looking at two pieces of literature, the Enuma Elish and the Gilgamesh epic. The Enuma Elish is — both of them are Mesopotamian in origin. One deals more with creation and the other deals a little bit more with flood parallels, parallels to the flood story, the Noah story. But again, you’ll see that the parallels — there are themes, ideas, images, concepts that are repeated but, you know, there was no plagiarism involved. Let’s talk a little bit about ancient Near Eastern literature and let’s just remember, number one, that ancient Israel was a nation, a vibrant nation, living within the context of the ancient Near Eastern world and it is natural that they would know of and be influenced and be aware of ideas, images that were inherent to the culture at that time. Ezekiel the prophet has been discussed by many as being a well-read intellectual of his day and of his location, making literary illusions to pieces of literature and ideas and concepts throughout his prophecy. And he’s just one example of how — a prominent example, in my mind — of how ancient Israelites were aware of the culture and the ideas that were going on around them. And again, it’s not that they took the Gilgamesh epic — and you’ll see that — or the Enuma Elish, or any other piece of literature and just scratched out the name Mesopotamia or whatever and put in the name Israel or put in the name Hebrew or put in the name Yahweh. -

Reading Guide: the Epic of Gilgamesh Prof

The Epic of Gilgamesh K 113355 Reading Guide: The Epic of Gilgamesh Prof. Stephen Hagin K Symbolic Connections in WL K 12th edition K Kennesaw State University Gilgamesh (Dalley, 39-125) If a person were to be placed on Pope’s isthmus, he/she would be torn between the two possible directions, limited to a choice between dualities. Is a human more like God or more like a beast? Should we value our minds or bodies more? Is society more important than Nature? Pope mentions that mankind is a great “riddle of the world” because we cannot make up our minds about our own natures. One duality is God/beast. Well, are we gods? Well, we can build things, we can fly in airplanes, and we can talk in virtual reality. However, we also have animalistic desires, we act for ourselves rather than our societies, and we ultimately face the fate of everything in Nature — death. So, we are not completely gods nor beasts, but we share the qualities of each. Pope’s thesis is that we are stuck in the middle because we share the natures of both sides of the duality. Once we lean in one direction, we begin to deny ourselves of the necessity to experience the other side as well. In Gilgamesh, we see the main character, King Gilgamesh, as a pure representation of the masculine side (the side that represents strength, society, God). Now that we have read literature from both the feminine and the masculine perspective, the next question to ask is, ‘Where is our proper place?” This answer will be revealed in this great myth.