Atra-Hasis: a Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

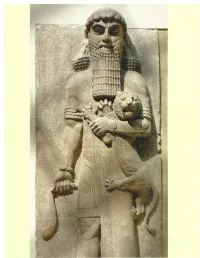

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

Early Dynastic Cuneiform Range: 12480–1254F

Early Dynastic Cuneiform Range: 12480–1254F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88094-7 - The Cambridge Companion to the Epic Edited by Catherine Bates Excerpt More information 1 A. R. GEORGE The Epic of Gilgamesh Introduction The name ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ is given to the Babylonian poem that tells the deeds of Gilgamesh, the greatest king and mightiest hero of ancient Mesopotamian legend. The poem falls into the category ‘epic’ because it is a long narrative poem of heroic content and has the seriousness and pathos that have sometimes been identified as markers of epic. Some early Assyri- ologists, when nationalism was a potent political force, characterized it as the ‘national epic’ of Babylonia, but this notion has deservedly lapsed. The poem’s subject is not the establishment of a Babylonian nation nor an episode in that nation’s history, but the vain quest of a man to escape his mortality. In its final and best-preserved version it is a sombre meditation on the human condition. The glorious exploits it tells are motivated by individ- ual human predicaments, especially desire for fame and horror of death. The emotional struggles related in the story of Gilgamesh are those of no collective group but of the individual. Among its timeless themes are the friction between nature and civilization, friendship between men, the place in the universe of gods, kings and mortals, and the misuse of power. The poem speaks to the anxieties and life-experience of a human being, and that is why modern readers find it both profound and enduringly relevant. Discovery and recovery The literatures of ancient Mesopotamia, chiefly in Sumerian and Babylonian (Akkadian), were lost when cuneiform writing died out in the first century ad. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Mesopotamian Epic."

' / Prof. Scott B. Noege1 Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington "Mesopotamian Epic." First Published in: John Miles Foley, ed. The Blackwell Companion to Ancient Epic London: Blackwell (2005), 233-245. ' / \.-/ A COMPANION TO ANCIENT EPIC Edited by John Miles Foley ~ A Blackwell '-II Publishing ~"o< - -_u - - ------ @ 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right ofJohn Miles Foley to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2005 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to ancient epic / edited by John Miles Foley. p. cm. - (Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Literature and culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4051-0524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Epic poetry-History and criticism. 2. Epic literature-History and criticism. 3. Epic poetry, Classical-History and criticism. I. Foley, John Miles. II. Series. PN1317.C662005 809.1'32-dc22 2004018322 ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-0524-8 (hardback) A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. -

Cuneiform Sign List ⊭ ⅗⋼⊑∾ ⊭‸↪≿

CUNEIFORM SIGN LIST ⊭ ⅗⋼⊑∾ ⊭‸↪≿ Kateřina Šašková Pilsen 2021 CONTENTS Cuneiform Sign List...........................................................................................................................3 References and Sources.................................................................................................................511 Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................513 2 CUNEIFORM SIGN LIST AŠ 001 001 U+12038 (ASH) (1, ANA , AS , AṢ , AŠ ‸ 3 3 3 ‸ (MesZL: see also U.DAR (nos. 670+183)), AŠA, AŠŠA, AZ3, DAL3, DEL, DELE, DEŠ2, DIL, DILI, DIŠ2, EŠ20, GE15, GEŠ4 (MesZL: perhaps to be erased, Deimel GEŠ), GUBRU2 (Labat; MesZL: GUBRU2 read LIRU2), ḪIL2 (Labat; MesZL: ḪIL2 missing), IN6 (MesZL: Labat IN3; Labat: IN6), INA, LIRI2 (MesZL: Labat GUBRU2), LIRU2 (MesZL: Labat GUBRU2), LIRUM2 (MesZL: Labat GUBRU2), MAKAŠ2, MAKKAŠ2, RAM2 (MesZL: ?), RIM5, RU3, RUM, SAGTAG, SAGTAK, SALUGUB, SANTA, SANTAG, SANTAK, SIMED (Labat: in index, in syllabary missing; 3 MesZL: SIMED missing), ŠUP2 (MesZL: Labat ŠUP3), ŠUP3 (Labat; MesZL: ŠUP2, ŠUP3 = ŠAB (no. 466)), TAL3, TIL4, ṬIL, UBU (Labat: in index, in syllabary missing; MesZL: UBU = GE23 (no. 575)), UTAK (Labat: in index, in syllabary missing; MesZL: UTAK = GE22 (no. 647))) (ePSD; Akkadian Dictionary) AŠ.DAR (MesZL: also AŠ.TAR2, old form of U.DAR (no. U+12038 & 670), see also U+1206F 001+183 001+114 (ASH & GE23.DAR (no. 575) ‸ ‸ DAR) and DIŠ.DAR (no. 748)) (ePSD; Akkadian Dictionary) -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh 47 The Epic of Gilgamesh Perhaps arranged in the fifteenth century B.C., The Epic of Gilgamesh draws on even more ancient traditions of a Sumerian king who ruled a great city in what is now southern Iraq around 2800 B.C. This poem (more lyric than epic, in fact) is the earliest extant monument of great literature, presenting archetypal themes of friendship, renown, and facing up to mortality, and it may well have exercised influence on both Genesis and the Homeric epics. 49 Prologue He had seen everything, had experienced all emotions, from ex- altation to despair, had been granted a vision into the great mystery, the secret places, the primeval days before the Flood. He had jour- neyed to the edge of the world and made his way back, exhausted but whole. He had carved his trials on stone tablets, had restored the holy Eanna Temple and the massive wall of Uruk, which no city on earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares. Find the cornerstone and under it the copper box that is marked with his name. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Semantikon.com presents An Old Babylonian Version of the Gilgamesh Epic On the Basis of Recently Discovered Texts By Morris Jastrow Jr., Ph.D., LL.D. Professor of Semitic Languages, University of Pennsylvania And Albert T. Clay, Ph.D., LL.D., Litt.D. Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature, Yale University In Memory of William Max Müller (1863-1919) Whose life was devoted to Egyptological research which he greatly enriched by many contributions PREFATORY NOTE The Introduction, the Commentary to the two tablets, and the Appendix, are by Professor Jastrow, and for these he assumes the sole responsibility. The text of the Yale tablet is by Professor Clay. The transliteration and the translation of the two tablets represent the joint work of the two authors. In the transliteration of the two tablets, C. E. Keiser's "System of Accentuation for Sumero-Akkadian signs" (Yale Oriental Researches--VOL. IX, Appendix, New Haven, 1919) has been followed. INTRODUCTION. I. The Gilgamesh Epic is the most notable literary product of Babylonia as yet discovered in the mounds of Mesopotamia. It recounts the exploits and adventures of a favorite hero, and in its final form covers twelve tablets, each tablet consisting of six columns (three on the obverse and three on the reverse) of about 50 lines for each column, or a total of about 3600 lines. Of this total, however, barely more than one-half has been found among the remains of the great collection of cuneiform tablets gathered by King Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.) in his palace at Nineveh, and discovered by Layard in 1854 [1] in the course of his excavations of the mound Kouyunjik (opposite Mosul). -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

COREComp. by: PG0963 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 9780521880947c01 Date:29/ Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk 11/09 Time:13:00:38 Filepath:H:/01_CUP/3B2/Bates-9780521880947/ ProvidedApplications/3B2/Proof/9780521880947c01.3d by SOAS Research Online 1 A. R. GEORGE The Epic of Gilgamesh Introduction The name ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ is given to the Babylonian poem that tells the deeds of Gilgamesh, the greatest king and mightiest hero of ancient Mesopotamian legend. The poem falls into the category ‘epic’ because it is a long narrative poem of heroic content and has the seriousness and pathos that have sometimes been identified as markers of epic. Some early Assyri- ologists, when nationalism was a potent political force, characterized it as the ‘national epic’ of Babylonia, but this notion has deservedly lapsed. The poem’s subject is not the establishment of a Babylonian nation nor an episode in that nation’s history, but the vain quest of a man to escape his mortality. In its final and best-preserved version it is a sombre meditation on the human condition. The glorious exploits it tells are motivated by individ- ual human predicaments, especially desire for fame and horror of death. The emotional struggles related in the story of Gilgamesh are those of no collective group but of the individual. Among its timeless themes are the friction between nature and civilization, friendship between men, the place in the universe of gods, kings and mortals, and the misuse of power. The poem speaks to the anxieties and life-experience of a human being, and that is why modern readers find it both profound and enduringly relevant. -

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh- King of Uruk, the Strongest of Men, and the Perfect Example of All Human Virtues. a Brave

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh - King of Uruk, the strongest of men, and the perfect example of all human virtues. A brave warrior, fair judge, and ambitious builder, Gilgamesh surrounds the city of Uruk with magnificent walls and erects its glorious ziggurats, or temple towers. Two-thirds god and one-third mortal, Gilgamesh is undone by grief when his beloved companion Enkidu dies, and by despair at the fear of his own extinction. He travels to the ends of the Earth in search of answers to the mysteries of life and death. Enkidu - Companion and friend of Gilgamesh. Hairy-bodied and muscular, Enkidu was raised by animals. Even after he joins the civilized world, he retains many of his undomesticated characteristics. Enkidu looks much like Gilgamesh and is almost his physical equal. He aspires to be Gilgamesh’s rival but instead becomes his soul mate. The gods punish Gilgamesh and Enkidu by giving Enkidu a slow, painful, inglorious death for killing the demon Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Aruru - A goddess of creation who fashioned Enkidu from clay and her saliva. Humbaba - The fearsome demon who guards the Cedar Forest forbidden to mortals. Humbaba’s seven garments produce a feeling that paralyzes fear in anyone who would defy or confront him. He is the prime example of awesome natural power and danger. His mouth is fire, he roars like a flood, and he breathes death, much like an erupting volcano. In his very last moments he acquires personality and pathos, when he pleads cunningly for his life. Siduri - The goddess of wine-making and brewing. -

Mesopotamian Society Was a Man the TRANSITION Named Gilgamesh

y far, the most familiar individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man THE TRANSITION named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth TO AGRICULTURE king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C. E., and he led his community The Paleolithic Era in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. The Neolithic Era Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as his tory. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards THE QUEST FOR ORDER made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as the Epic of Mesopotamia: "The Land Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of between the Rivers" ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a per The Course of Empire fect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. The legends declare that he constructed the massive city walls of Uruk as well as several of the THE FORMATION OF A COMPLEX SOCIETY city's magnificent temples to Mesopotamian deities. AND SOPHISTICATED The stories that make up the Epic of Gi/gamesh recount the adventures of this CULTURAL TRADITIONS hero and his cherished friend Enkidu as they sought fame. They killed an evil mon Economic Specialization ster, rescued Uruk from a ravaging bull, and matched wits with the gods. In spite of and Trade their heroic deeds, Enkidu offended the gods and fell under a sentence of death. The Emergence of a His loss profoundly affected Gilgamesh, who sought The Epic of Gilgamesh Stratified Patriarchal Society for some means to cheat death and gain eternal www.mhhe.com/ • bentleybrief2e The Development of Written life. -

Death in Sumerian Literary Texts

Death in Sumerian Literary Texts Establishing the Existence of a Literary Tradition on How to Describe Death in the Ur III and Old Babylonian Periods Lisa van Oudheusden s1367250 Research Master Thesis Classics and Ancient Civilizations – Assyriology Leiden University, Faculty of Humanities 1 July 2019 Supervisor: Dr. J.G. Dercksen Second Reader: Dr. N.N. May Table of Content Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... 4 Chapter One: Introducing the Texts ............................................................................... 5 1.1 The Sources .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1.2 Main Sources ................................................................................................. 6 1.1.3 Secondary Sources ......................................................................................... 7 1.2 Problems with Date and Place .............................................................................. 8 1.3 History of Research ............................................................................................ 10 Chapter Two: The Nature of Death .............................................................................. 12 2.1 The God Dumuzi ...............................................................................................