Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South American Camelids – Origin of the Species

SOUTH AMERICAN CAMELIDS – ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES PLEISTOCENE ANCESTOR Old World Camels VicunaLLAMA Guanaco Alpaca Hybrids Lama Dromedary Bactrian LAMA Llamas were not always confined to South America; abundant llama-like remains were found in Pleistocene deposits in the Rocky Mountains and in Central America. Some of the fossil llamas were much larger than current forms. Some species remained in North America during the last ice ages. Llama-like animals would have been a common sight in 25,000 years ago, in modern-day USA. The camelid lineage has a good fossil record indicating that North America was the original home of camelids, and that Old World camels crossed over via the Bering land bridge & after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama three million years ago; it allowed camelids to spread to South America as part of the Great American Interchange, where they evolved further. Meanwhile, North American camelids died out about 40 million years ago. Alpacas and vicuñas are in genus Vicugna. The genera Lama and Vicugna are, with the two species of true camels. Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) is a domesticated species of South American camelid. It resembles a small llama in superficial appearance. Alpacas and llamas differ in that alpacas have straight ears and llamas have banana-shaped ears. Aside from these differences, llamas are on average 30 to 60 centimeters (1 to 2 ft) taller and proportionally bigger than alpacas. Alpacas are kept in herds that graze on the level heights of the Andes of Ecuador, southern Peru, northern Bolivia, and northern Chile at an altitude of 3,500 m (11,000 ft) to 5,000 m (16,000 ft) above sea-level, throughout the year. -

ELA Grade 6 Unit 2 - Open Response - Print

Name: Class: Date: ELA Grade 6 Unit 2 - Open Response - Print 1 Another lesson. So that was the way they did it, eh? Buck Excerpt from The Call of the Wild confidently selected a spot, and with much fuss and waste by Jack London effort proceeded to dig a hole for himself. In a trice the heat from his body filled the confined space and he was That night Buck faced the great problem of sleeping. The asleep. The day had been long and arduous, and he slept tent, illumined by a candle, glowed warmly in the midst of soundly and comfortably, though he growled and barked the white plain; and when he, as a matter of course, and wrestled with bad dreams. entered it, both Perrault and Francois bombarded him with curses and cooking utensils, till he recovered from his Nor did he open his eyes till roused by the noises of the consternation and fled ignominiously into the outer cold. A waking camp. At first he did not know where he was. It chill wind was blowing that nipped him sharply and bit with had snowed during the night and he was completely especial venom into his wounded shoulder. He lay down buried. The snow walls pressed him on every side, and a on the snow and attempted to sleep, but the frost soon great surge of fear swept through him—the fear of the wild drove him shivering to his feet. Miserable and thing for the trap. It was a token that he was harking back disconsolate, he wandered about among the many tents, through his own life to the lives of his forebears; for he only to find that one place was as cold as another. -

Livestock Important Animals on the Farm

Canadian Foodgrains Bank Livestock Important Animals on the Farm Did you know? There are many types of livestock in the world. Which of these animals have you seen? Cows Alpaca Sheep Camel Goats Gayal Pigs Llama Chickens Water buffalo Turkeys Yak This picture is of a girl from Ethiopia, holding a New words pair of goats. In many cultures around the world Here are some new words you can learn that refer domesticated animals, called livestock, are a very to livestock! important source of food and income (money). Baby animals can be sold and the money used to Draught – (pronounced “draft”) A draught animal pay for other important things like school fees. is an animal that is very strong and is used for Livestock can be useful for wool, leather or fur, tasks such as ploughing or logging. used mostly for clothing but also for homes, tools and other household goods. Livestock is also Mount – A mount is an animal that can be ridden used as helpers on the farm! by people, such as horses or camels. Sometimes, in situations of extreme hunger Pack– A pack animal is an animal that is used to and famine, families will sell their livestock in carry supplies or people. order to buy food. This is a big problem because families might not get very much money for their livestock during famine times. Since livestock are Name these livestock animals important for food (for milk, meat, and help on the farm), it is even more difficult for people to feed themselves after their livestock is gone, even if there is food growing in the fields. -

Assessment of Pack Animal Welfare in and Around Bareilly City of India

doi:10.5455/vetworld.2013.332-336 Assessment of pack animal welfare in and around Bareilly city of India Probhakar Biswas, Triveni Dutt, M. Patel, Reena Kamal, P.K. Bharti and Subhasish Sahu Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar - 243122, Dist. Bareilly (UP) India Corresponding author: Probhakar Biswas, email:[email protected] Received: 22-09-2012, Accepted: 06-10-2012, Published online: 15-03-2013 How to cite this article: Biswas P, Dutt T, Patel M, Kamal R, Bharti PK and Sahu S (2013) Assessment of pack animal welfare in and around Bareilly city of India, Vet. World 6(6):332-336, doi:10.5455/vetworld.2013.332-336 Abstract Aim: To assess the welfare of pack animal: Pony, Horse, Mule and Donkey in and around Bareilly city. Materials and Methods: The present study was carried out in Bareilly city and Izatnagar area of Bareilly district of Uttar Pradesh in the year 2009. Representative sample of 100 pack animal owners were selected to get the information regarding various social, personal and economic attributes of the pack animal. Further during interviewing different health and behavior pattern of animals was keenly examined. Analysis has been done as per standard procedures. Results: Most of the pack animal owners (98%) were aware of the freedom from hunger and thirst. Majority of respondents (96, 93, 81 & 85 percent) were aware of freedom from injury and disease, pain and discomfort, to express normal behavior and adequate space and freedom from fear and distress. Respondents (85%) believed that they themselves were responsible for the welfare of the animals. -

Dogs of War: the Biopolitics of Loving and Leaving the U.S. Canine Forces in Vietnam

Animal Studies Journal Volume 2 Number 1 Article 6 2013 Dogs of War: The Biopolitics of Loving and Leaving the U.S. Canine Forces in Vietnam Ryan Hediger Kent State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Recommended Citation Hediger, Ryan, Dogs of War: The Biopolitics of Loving and Leaving the U.S. Canine Forces in Vietnam, Animal Studies Journal, 2(1), 2013, 55-73. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol2/iss1/6 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Dogs of War: The Biopolitics of Loving and Leaving the U.S. Canine Forces in Vietnam Abstract This essay uses Michel Foucault’s notion of biopower to explore how dogs were used by the United States military in the Vietnam wars to mitigate the territorial advantages of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army. Relying in particular on the account by U.S. soldier and dog handler John C. Burnam, the essay also shows agency to be situational: since the dogs’ superior sensory abilities enabled them to help significantly the United States military, their presence complicates and at times reverses dogmatic ideas of human agency trumping other animals’ agency. But the operation of contemporary biopower makes such categorical inversions flimsy and er versible: the dogs’ status changed from heroes set for moments above human soldiers to mere machinery, pressed below even animals, in order to excuse official United States policy to leave the dogs in Vietnam. -

Reproductive Control of Elephants

6 Reproductive control of elephants Lead author: Henk Bertschinger Author: Audrey Delsink Contributing authors: JJ van Altena, Jay Kirkpatrick, Hanno Killian, Andre Ganswindt and Rob Slotow Introduction HAPTER 6 deals specifically with fertility control as a possible means of Cpopulation management of free-ranging African elephants. Because methods that are described here for elephants function by preventing cows from conceiving, fertility control cannot immediately reduce the population. This will only happen once mortality rates exceed birth rates. Considering, however, that elephants given the necessary resources can double their numbers every 15 years, fertility control may have an important role to play in population management. The first part of the chapter is devoted to the reproductive physiology of elephants in order to provide the reader with information and understanding which relate to fertility control. This is followed by examples of contraceptive methods that have been used in mammals, and a description of past and ongoing research specifically carried out in elephants. Finally guidelines for a contraception programme are provided, followed by a list of key research issues and gaps in our knowledge of elephants pertaining to reproduction and fertility control. In this chapter we will also attempt to answer the following questions in regard to reproductive control of African elephants: • Do antibodies to the porcine zona pellucida (pZP) proteins recognise elephant zona pellucida (eZP) proteins or is the vaccine likely to -

THE MARITIME TROY CULTURE (C. 3000-2200 BC.) Dissertation PART

ANIMAL BASED ECONOMY IN TROIA AND THE TROAS DURING THE MARITIME TROY CULTURE (C. 3000-2200 BC.) AND A GENERAL SUMMARY FOR WEST ANATOLIA Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie der Geowissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen PART I TEXT vorgelegt von Can Yümni GÜNDEM aus Adana/Türkei 2010 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 19. 01. 2010 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Peter Grathwohl 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Dr. Hans Peter Uerpmann 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Nicholas J. Conard EIDESSTATTLICHE VERSICHERUNG Hiermit versichere ich, dass die vorliegende Arbeit mit dem Titel „ Animal Based Economy in Troia and the Troas during The Maritime Troy Culture (c. 3000-2200 BC.) and a General Summary for West Anatolia “ selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der von mir angegebenen Hilfsmittel verfasst habe. Alle Stellen, die wortgetreu oder sinngemäß aus anderen Veröffentlichungen entnommen sind, wurden als solche kenntlich gemacht. Diese Arbeit hat noch keine anderen Stellen zum Zwecke der Erlangung eines Doktor-Grades vorgelegt. Tübingen, 2010 (Can Yümni Gündem) 2 This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved aunt Handan Sezen (†) , to my dear pal Horst Trossbach (†) and to my wonderful family Fatma Bengü, Suavi, Ali, Meltem and Almira Ece 3 Content Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 17 Summary................................................................................................................................ -

Pack Animal Handling Course

PACK ANIMAL HANDLING COURSE LITTLE BIGHORN STAFF RIDE: Learn the secrets of the Little Bighorn Battle from the back of a horse, on the Other Programs Available: banks of the Little Bighorn River, and in the classes taught at our Cavalry encamp- Mobile Training Team (2 - 7 Days) ment from military historians and local Custer’s Last Ride Cavalry Training & Native Americans. This staff Ride is a su- perb teambuilding event. Little Bighorn Reenactment (8 Days) Cavalry Encampment (4-6 Days) Our professional staff includes retired Weekend Workshop (2 Days) military officers and NCO’s (some with active Army Cavalry Service); Frontier Ar- School of the Trooper (.5 Hr - 1 Day) my and Native American Scholars, experi- Gun Training for Horse and Rider (Vary) enced movie re-enactors, horsemen, mule CIVILIAN AND skinners, and respected outfitters. Our Staff Ride (Battles and Lengths Vary) MILITARY PACKING Staff Ride lead instructor(s) have taught numerous Active Duty Staff Rides on the COURSES, TO INCLUDE Little Bighorn and elsewhere. COMBAT RIDING & P.O. Box 136 Ft Harrison, MT 59636 www.uscavalryschool.com HIGH MOUNTAIN PACK TRAINING Call 888-291-4097 or 406-461-3614. Copyright © 2001 U.S. Cavalry School, Inc. All rights reserved. US Cavalry School: Pack Animal Course (1 to 14 Days): We teach the basic and advanced tech- niques of packing a Supply/PACK Ani- mal (Mule, Horse, or Donkey). Our lead Specializing in difficult loads of odd size Little Bighorn Battle/Cavalry School: instructor has been a professional outfitter loads and sensitive/fragile equipment in Our encampment is held on this sacred with over 25 years experience in manag- extreme terrain. -

Mundane Beasts

Ars Magica Mundane Beasts The beasts of Mythic Europe are not quite the same as normal animals in the real world. Modifying New Virtues The ferocity of wild animals, in particular, is Beast Sizes for Beasts exaggerated for dramatic purposes. In Mythic Europe, it is not uncommon for beasts such as wolves to attack humans. Some beasts cover a range of Size cat- Ferocity (minor, beasts only): Like egories, and any beast might have its Size a magus or companion character, you have magically altered. To increase the Size of a Confidence points. Unlike a human character, beast, add 2 points of Strength and subtract you may use your Confidence Points only in one point of Quickness for each point of Size situations where your natural animal ferocity is added. To decrease size, subtract 2 points of triggered, such as when defending your den or Beast Strength and add one point of Quickness for fighting a natural enemy. Describe a situation each point of Size subtracted. Update combat that activates your Confidence score, and take statistics according to the new Characteristics. three points for you to use when those circum- Statistics Larger animals are more powerful, but rela- stances are met. tively ungainly. Beasts' Characteristics may take any value, even exceeding -5 or +5. Beasts do not need a Virtue or Flaw to have Characteristics outside the normal human range of -3 to +3. Their starting Characteristics depend on their Beasts ecological niche (predator, herbivore, etc.) Beast Virtues, and are different from the average human Characteristics of all zeroes. in Combat As stated in ArM5, p. -

Packing with Horses & Mules

Back Country Horsemen of Montana PACKING WITH HORSES & MULES Horsemen’s Creed—When I ride out of the mountains, I’ll leave only hoof prints, take only memories. The purpose of this packing booklet is to provide basic information in an organized manner to help you learn about horses and equipment and to effectively plan and take pack trips in the back country. Use of qualified persons to help with the teaching of packing fundamentals and back country safety will make packing easier and more fun. Packing as a hobby, or as a business, can be very enjoyable with the proper equipment, a basic knowledge of the horse, good camping equipment, a sound trip itinerary, well-thought-out menus, and other details will help to make a well-rounded pack trip. The Back Country Horsemen of Montana is dedicated to protecting, preserving and improving the back country resource by volunteering time and equipment to government agencies for such tasks as clearing trails, building trails, building trailhead facilities, packing out trash and other projects that will benefit both horsemen and non-horsemen. Mission Statement To perpetuate the common sense use and enjoyment of horses in America’s back country, roadless backcountry and wilderness areas; To work to ensure that public lands remain open to recreational stock use; To assist the various government and private agencies in their maintenance and management of said resource; To educate, encourage and solicit active participation by the general public in the wise and sustaining use of the back country resource by horses and people commensurate with our heritage; To foster and encourage the formation of new state back country horsemen organizations; To seek out opportunities to enhance existing areas of recreation for stock users. -

Course 306. Working with Packers and Packstock

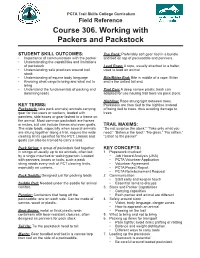

PCTA Trail Skills College Curriculum Field Reference Course 306. Working with Packers and Packstock STUDENT SKILL OUTCOMES: Top Pack: Preferably soft gear tied in a bundle • Importance of communication with the packer and tied on top of packsaddle and panniers. • Understanding the capabilities and limitations of packstock Lead Rope: A rope, usually attached to a halter, • Understanding safe practices around trail used to lead an animal stock • Understanding of equine body language Bite/Bitter End: Bite is middle of a rope. Bitter • Knowing what cargo to bring and what not to end is the untied tail end. bring • Understand the fundamentals of packing and Tool Can: A deep narrow plastic trash can balancing loads adapted for use hauling trail tools via pack stock. Highline: Rope strung tight between trees. KEY TERMS: Packstock are then tied to the highline instead Packstock: (aka pack animals) animals carrying of being tied to trees, thus avoiding damage to gear for trail users or workers, loaded with trees. panniers, side boxes or gear lashed to a frame on the animal. Most common packstock are horses or mules, but can include llamas and even goats. TRAIL MAXIMS: The wide loads, especially when several animals “Do not surprise the stock,” “Take only what you are strung together along a trail, require the wide need,” “Balance the load,” “No glass,” “No rattles,” clearing limits specified for the PCT. Llamas and “Listen to the packer” goats can also be trained to carry a load. Pack String: a group of packstock tied together KEY CONCEPTS: in strings of usually up to six animals, often led 1. -

Canine Communication Peaceful Pack

Canine Communication Peaceful Pack Mia Semuta Canine Communication, Peaceful Pack Mia Semuta Dogs are amazing creatures. From once wild animals to domesticated companions over the course of a few thousand years, they have become such an integral part of our society that they now exist as members of the family. Just as a human member of your family needs to learn the rules and abide by them to maintain a harmonious household, so does your dog. As with all relationships: communication is key. The tricky part is learning how to communicate with your dog in a manner that is understood. Once you unlock that obstacle then the sky is the limit for the joy and satisfaction that you and your canine family member will enjoy. Dogs are primarily concerned about two things: Who’s in charge? What’s my job? Gigi, Stewie and Pony on place waiting to be called to dinner. As a pack animal it is a dog’s nature to strive to live in harmony with those around him. Dogs that “don’t like other dogs” are often afraid and have not been properly socialized. Dogs that “don’t like strangers” have not always been abused but they don’t have a strong sense of security in their pack leader’s ability to lead. Dogs that “only do what I say when I have a treat” don’t really understand what you’re saying. It is totally possible to learn how to be the strong leader your dog needs, how to properly socialize your dog and how to speak to your dog in a language that is natural to him.