BIBLIOGRAPHY Since Al Smith and His Closest Associates Left So Little In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 New York No Numbers

NEW YORK, NEW YORK A list celebrating the city that – until last month – never sleeps. These 50 selections reflect the city’s important contributions to history, art, music, literature, cuisine, engineering, transportation, architecture, and leisure. This is an enhanced PDF catalog. If you click on an image or the highlighted headline of any entry, you will be linked to our website where you will find images. We are happy to provide more images or information upon request. In chronological order 1. HARDIE, James. The Description of the City of New York. New York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 360 pages. Hand-colored engraved folding map. Contemporary sheep, gilt decorated on spine. Provenance: contemporary ownership inscription on front free endpaper. Binding worn, occasional pale spotting. Large folding map has a small tear at the attachment else very clean and bright. $325 FIRST EDITION. Church 1336; Howes H-184. Sabin 30319. RIVERRUN BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS NEW YORK HYDRATED 2. RENWICK, James. Report on the Water Power at Kingsbridge near the City of New-York, Belonging to New- York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company. New-York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 12 pages. Three folding lithographed maps, printed by Imbert. Sewn in original printed wrappers, untrimmed; blue cloth portfolio. Provenance: contemporary signature on front wrapper of D. P. Campbell at 51 Broadway. Wear to wrappers, some light foxing, maps clean and bright. $1,200 FIRST EDITION of this scarce pamphlet on the development of the New York water supply. Renwick was Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and Chemistry at Columbia College, and writes at the request of the directors of the New York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company who asked him to examine their property at Kingsbridge. -

A Vision for the South Shore Bayway George E. Pataki, Governor

George E. Pataki, Governor Randy A. Daniels, Secretary of State A Vision for The South Shore Bayway Long Island South Shore Estuary Reserve January, 2004 This report was prepared with financial assistance from the New York State Environmental Protection Fund and the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. A Vision for The South Shore Bayway Long Island South Shore Estuary Reserve January, 2004 Prepared for the South Shore Estuary Reserve Council with assistance from the South Shore Estuary Reserve Office and the New York State Department of State, Division of Coastal Resources Picture a network of trails, scenic roads and bike lanes leading to the beautiful waters of Long Islandʼs south shore bays.... Gardiner County Park, West Bay Shore Imagine a coordinated system of signs, exhibits and street improvements leading the way to the shoreline.... Waterfront Access, Patchogue Envision exploring the bays, barrier beaches and tributaries alone in a kayak or with friends on a sunset cruise.... Santopogue Creek, Lindenhurst Picture Long Islanders and visitors better connected with the beauty, history and natural splendor of the South Shore Estuary.... View across Bay to Fire Island You are experiencing the new Long Island South Shore Bayway! A Vision for The South Shore Bayway Page 1 The Vision The South Shore Estuary Reserve Bayway will be an interwoven interpretation of and access network of existing maritime centers, parks, historic and cultural to the significant natural, sites, community centers, and waterfronts used by pedestrians, cultural and recreational bicyclists, boaters and motorists. -

Mayor and Speaker Launch NYC Waterfront Vision And

About Us > Press Releases FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 13, 2010 CONTACTS: Rachaele Raynoff (City Planning) -- (212) 720-3471 Stu Loeser / Andrew Brent (Mayor) -- (212) 788-2958 David Lombino / Libby Langsdorf (NYCEDC) (212) 312-3523 MAYOR BLOOMBERG AND SPEAKER QUINN LAUNCH NYC WATERFRONT VISION AND ENHANCEMENT STRATEGY (WAVES) – A BLUEPRINT FOR NEW YORK CITY'S 578 MILES OF WATERFRONT New Framework Will Establish Priority Initiatives for the Next Three Years and Long-Term Goals for the Next Decade and Beyond, Complementing and Advancing the Goals of PlaNYC Waterfront Plan Commences as City Expands its Authority to Lead the Futures of Governors Island and Brooklyn Bridge Park Public Workshops in All Five Boroughs Begin this Spring Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine C. Quinn today launched the New York City Waterfront Vision and Enhancement Strategy (WAVES), a citywide initiative that will create a new sustainable blueprint for the City’s 578 miles of shoreline. The WAVES strategy – to be developed over the next nine months – will include two core components: the Vision 2020 – The New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan that will establish long-term goals for the next decade and beyond, and the New York City Waterfront Action Agenda that will set forth priority initiatives to be implemented within three years. Together, the initiatives will provide a blueprint for the City’s waterfront and waterways, and focus on the following categories: open space and recreation, the working waterfront, housing and economic development, natural habitats, climate change adaptation and waterborne transportation. A series of public workshops in all five boroughs to discuss the waterfront strategy will begin this spring. -

Rochdale Village and the Rise and Fall of Integrated Housing in New York City by Peter Eisenstadt

Rochdale Village and the rise and fall of integrated housing in New York City by Peter Eisenstadt When Rochdale Village opened in southeastern Queens in late 1963, it was the largest housing cooperative in the world. When fully occupied its 5,860 apartments contained about 25,000 residents. Rochdale Village was a limited-equity, middle-income cooperative. Its apartments could not be resold for a profit, and with the average per room charges when opened of $21 a month, it was on the low end of the middle-income spectrum. (3) It was laid out as a massive 170 acre superblock development, with no through streets, and only winding pedestrian paths, lined with newly planted trees, crossing a greensward connecting the twenty massive cruciform apartment buildings. Rochdale was a typical urban post-war housing development, in outward appearance differing from most others simply in its size. It was, in a word, wrote historian Joshua Freeman, "nondescript." (4) Appearances deceive. Rochdale Village was unique; the largest experiment in integrated housing in New York City in the 1960s, and very likely the largest such experiment anywhere in the United States (5). It was located in South Jamaica, which by the early 1960s was the third largest black neighborhood in the city. Blacks started to move to South Jamaica in large numbers after World War I, and by 1960 its population was almost entirely African American. It was a neighborhood of considerable income diversity, with the largest tracts of black owned private housing in the city adjacent to some desperate pockets of poverty. -

Snap That Sign 2021: List of Pomeroy Foundation Markers & Plaques

Snap That Sign 2021: List of Pomeroy Foundation Markers & Plaques How to use this document: • An “X” in the Close Up or Landscape columns means we need a picture of the marker in that style of photo. If the cell is blank, then we don’t need a photo for that category. • Key column codes represent marker program names as follows: NYS = New York State Historic Marker Grant Program L&L = Legends & Lore Marker Grant Program NR = National Register Signage Grant Program L&L marker NYS marker NR marker NR plaque • For GPS coordinates of any of the markers or plaques listed, please visit our interactive marker map: https://www.wgpfoundation.org/history/map/ Need Need Approved Inscription Address County Key Close Up Landscape PALATINE TRAIL ROAD USED FOR TRAVEL WEST TO SCHOHARIE VALLEY. North side of Knox Gallupville Road, AS EARLY AS 1767, THE Albany X NYS Knox TOWN OF KNOX BEGAN TO GROW AROUND THIS PATH. WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2015 PAPER MILLS 1818 EPHRAIM ANDREWS ACQUIRES CLOTH DRESSING AND County Route 111 and Water Board Rdl, WOOL CARDING MILLS. BY 1850 Albany X NYS Coeymans JOHN E. ANDREWS ESTABLISHES A STRAW PAPER MAKING MILL WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2014 FIRST CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF 405 Quail Street, Albany Albany x x NR ALBANY RAPP ROAD COMMUNITY HISTORIC DISTRICT 28 Rapp Road, Albany Albany x NR CUBA CEMETERY Medbury Ave, Cuba Allegany x x NR CANASERAGA FOUR CORNERS HISTORIC 67 Main St., Canaseraga Allegany x NR DISTRICT A HAIRY LEGEND FIRST SIGHTED AUG 18, 1926 HAIRY WOMEN OF KLIPNOCKY, ONCE YOUNG GIRLS, INHABIT 1329 County Route 13C, Canaseraga Allegany x L&L THIS FOREST, WAITING FOR THEIR PARENTS' RETURN. -

Robert Moses Replies to Robert Caro

We Live in a Motorized Civilization: Robert Moses Replies to Robert Caro Geoff Boeing Department of Urban Planning and Spatial Analysis University of Southern California April 2021 Introduction In 1974, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. published Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, a critical biog- raphy of Robert Moses’s dictatorial tenure as the “master builder” of mid-century New York. Moses profoundly transformed New York’s urban fabric and transportation sys- tem, producing the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, the West- side Highway, the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Lincoln Center, the UN headquarters, Shea Stadium, Jones Beach State Park, and many other projects. However, The Power Broker did lasting damage to his public image and today he remains one of the most con- troversial figures in city planning history. Caro’s book won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize and was eventually named one of the Modern Library’s 100 greatest nonfiction books of the twentieth century. Prior to this critical acclaim, however, came a pointed response from arXiv:2104.06179v1 [econ.GN] 26 Mar 2021 the biography’s subject. On August 26, 1974, Moses issued a turgid 23-page statement denouncing Caro’s work as “full of mistakes, unsupported charges, nasty baseless personalities, and random haymakers.” In his statement, Moses denied having had any responsibility for mass tran- sit, dismissed his “lady critics,” and defended the forced displacement of the poor as a necessary component of urban revitalization: “I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs.” The statement also included a striking passage on what Moses perceived to be his critics’ hypocrisies in the modern age of automobility: “One cannot help being 1 amused by my friends among the media who shout for rails and inveigh against rubber but admit that they live in the suburbs and that their wives are absolutely dependent on motor cars. -

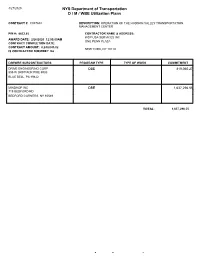

NYS Department of Transportation D / M / WBE Utilization Plans

4/27/2020 NYS Department of Transportation D / M / WBE Utilization Plans CONTRACT #: C037694 DESCRIPTION: OPERATION OF THE HUDSON VALLEY TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT CENTER PIN #: 8823.85 CONTRACTOR NAME & ADDRESS: WSP USA SERVICES INC AWARD DATE: 2/26/2020 12:00:00AM ONE PENN PLAZA CONTRACT COMPLETION DATE: CONTRACT AMOUNT: 8,240,043.02 NEW YORK, NY 10119 IS CONTRACTOR D/M/WBE? No D/M/WBE SUBCONTRACTORS PROGRAM TYPE TYPE OF WORK COMMITMENT DRIVE ENGINEERING CORP. DBE 819,060.27 595 W SKIPPACK PIKE #400 BLUE BELL, PA 19422 MINDHOP INC DBE 1,637,296.55 719 BEDFORD RD BEDFORD CORNERS, NY 10549 TOTAL: 1,637,296.55 4/27/2020 NYS Department of Transportation D / M / WBE Utilization Plans CONTRACT #: C037696 DESCRIPTION: STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION PLAN SERVICES FOR NYSDOT PIN #: P116.52 CONTRACTOR NAME & ADDRESS: ICF INCORPORATED, LLC AWARD DATE: 2/14/2020 12:00:00AM 9300 LEE HIGHWAY CONTRACT COMPLETION DATE: FAIRFAX, VA 22031 CONTRACT AMOUNT: 1,685,978.03 IS CONTRACTOR D/M/WBE? No D/M/WBE SUBCONTRACTORS PROGRAM TYPE TYPE OF WORK COMMITMENT ARCH STREET COMMUNICATIONS, INC. DBE 286,616.27 31 MAMARONECK AVENUE, SUITE 400 WHITEPLAINS, NY 10601 HIGHLAND PLANNING LLC DBA: HIGHLAND PLANNING DBE 134,878.24 17 MULBERRY STREET ROCHESTER, NY 14620 TOTAL: 286,616.27 4/27/2020 NYS Department of Transportation D / M / WBE Utilization Plans CONTRACT #: C037903 DESCRIPTION: OPERATION OF THE TRANSPORTATION MGMT. CENTER IN SYRACUSE PIN #: 3806.90 CONTRACTOR NAME & ADDRESS: GANNETT FLEMING MANAGEMENT SERVICES LLC AWARD DATE: 2/6/2020 12:00:00AM 207 SENATE AVE CONTRACT COMPLETION DATE: CAMP HILL, PA 17001 CONTRACT AMOUNT: 5,953,616.72 IS CONTRACTOR D/M/WBE? No D/M/WBE SUBCONTRACTORS PROGRAM TYPE TYPE OF WORK COMMITMENT KMJ CONSULTING, INC. -

County Executives Fight for Long Island's Fair Share, Calling for $3

BIWeekly e-gram ThaT conTaIns The laTesT neWs and Information vital To lICA’s memBers DECEMBer 7, 2010 In ThIs Issue County Executives Fight • COUNTY EXECUTIVES FIGHT FOR LONG ISLANd’S FAIR SHARE, CALLING FOR $3 for Long Island’s Fair Share, BILLION IN FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION FUNDING Calling for $3 Billion in • LICA SupportS ComptroLLer DINApoLI’S CALL FOR SWEEPING CHANGES TO STATE’S Federal Transportation Funding CAPITAL PLAN • The LoNg ISLAND CoNtrACtorS’ AssOCIATION SUppORTS PLAN TO ReDUce DEFICIT/STRENGTHEN U.S. TRANSPORTATION NETWORK • THE BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY DELIVER MEMO TO GOVERNOR- ELECT CUOMO: MAKE STATE’S INFRASTRUCTURE A MAIN PRIORITY • LICA memberS hoNoreD AS LIbN’S “Who’S WHO IN 2010” • LICA STRENGTHENS INDUSTRY’S ETHICAL STANDARDS • LICA TO WelcOme The HOLIDAys AT The WATERMILL ON DECEMBER 15TH • REGISTER NOW FOR LICA’S 2011 ANNUAL HEAVY CONSTRUCTION AND TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE SAFETY SEMINAR • 2011 CONEXPO IN LAS VEGAS, NEVADA LICA Executive Director Marc Herbst and Suffolk and Nassau County Executives Steve Levy and Ed Mangano were joined by the Long Island Association (LIA) • CHRISTMAS/NEW YEar’S EVE HOLIDAY SCHEDULES President Kevin Law at a recent press conference. • bID reSuLtS In the wake of New Jersey Governor Chris Christie cancelling one of the most important transportation public works projects in a generation, Suffolk and Nassau County Executives Steve Levy and Ed Mangano joined forces 150 Motor Parkway at a recent press conference to announce their bid for $3 billion of the $8.7 Suite 307 billion in federal transportation funding that would have gone to build the Hudson Hauppauge, NY 11788-5145 River rail tunnel. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of Ulster ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF ULSTER _______________________________________________ In the Matter of the Application of JB NICHOLAS, Petitioner, — against — Index No. ERIK KULLESEID, Acting Commissioner, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; JAMES F. HALL, Director, Palisade Interstate Park Commission; BASIL SEGGOS, Commissioner, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Respondents, For Judgment Pursuant to Article XIV, § 5 of the New York State Constitution and Articles 30 & 78 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules. ________________________________________________ MEMORANDUM OF LAW Statement of the Facts The great forests of the Catskills and Adirondacks were decimated in the 19th Century. Mining, logging, tanning, charcoal-making and forest fires destroyed what had been a vast, primeval wilderness. Unless action was taken to save what was left, "the ruthless burning and destruction of the forest" would continue, and "vast areas of naked rock, arid sand and gravel will alone remain," Verplanck Colvin, the State Surveyor, warned in a 1874 report for the State Legislature, Report on the Topographical Survey of the Adirondack Wilderness of New York for the year 1874. 1 In response, New York created the Forest Preserve. Signed into law by Governor David B. Hill, Chapter 283 of the laws of 1885 mandated that "All the lands now owned or which may hereafter be acquired by the State of New York within" 14 counties, including Ulster, "shall constitute and be known as the Forest Preserve." Id. § 7. Forest Preserve lands, the law said, "shall be forever kept as wild forest land. They shall not be sold, nor shall they be leased or taken by any person or corporation, public or private." Id. -

North Shore Sample

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Volume I Acknowledgments . iv Introduction . vii Maps of Long Island Estate Areas . xiv Factors Applicable to Usage . xvii Surname Entries A – M . 1 Volume II Surname Entries N – Z . 803 Appendices: ArcHitects . 1257 Civic Activists . 1299 Estate Names . 1317 Golf Courses on former NortH SHore Estates . 1351 Hereditary Titles . 1353 Landscape ArcHitects . 1355 Maiden Names . 1393 Motion Pictures Filmed at NortH SHore Estates . 1451 Occupations . 1457 ReHabilitative Secondary Uses of Surviving Estate Houses . 1499 Statesmen and Diplomats WHo Resided on Long Island's North Shore . 1505 Village Locations of Estates . 1517 America's First Age of Fortune: A Selected BibliograpHy . 1533 Selected BibliograpHic References to Individual NortH SHore Estate Owners . 1541 BiograpHical Sources Consulted . 1595 Maps Consulted for Estate Locations . 1597 PhotograpHic and Map Credits . 1598 I n t r o d u c t i o n Long Island's NortH SHore Gold Coast, more tHan any otHer section of tHe country, captured tHe imagination of twentieth-century America, even oversHadowing tHe Island's SoutH SHore and East End estate areas, wHich Have remained relatively unknown. THis, in part, is attributable to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, whicH continues to fascinate the public in its portrayal of the life-style, as Fitzgerald perceived it, of tHe NortH SHore elite of tHe 1920s.1 The NortH SHore estate era began in tHe latter part of the 1800s, more than forty years after many of the nation's wealtHy Had establisHed tHeir country Homes in tHe Towns of Babylon and Islip, along tHe Great SoutH Bay Ocean on tHe SoutH Shore of Long Island. -

ROBERT MOSES: His Contribution to NEW YORK CITY

ROBERT MOSES: his contribution to NEW YORK CITY Robert Moses is a controversial figure in urban planning. He is best known for shaping development in and around New York City. MOSES WHO ALWAYS Synopsis PREFERRED HIGHER SCALE Born in Connecticut in 1888, urban planner Robert Moses became one of the major shaping forces behind America's modern cities but PROJECTS WHICH GIVES was sometimes a figure of controversy and criticism. He transformed the city of New York by pushing for the construction of highways, MONUMENTAL VISIBILITY AS tunnels and bridges. He also helped preserve land for parks throughout New York state. He died in West Islip, New York, in 1981. WELL AS THOSE BRIDGES AND ROADS THAT CARRY MORE A Focus on Development NUMBER OF TRAFFIC THAN THE • Moses focused his attention on the greater New York City area, believing that TUNNELS, RESULTED IN the region needed development for automobiles and land preservation for CONSTRUCTION OF THE BRIDGE parks. SHOWN IN THE LEFT- • Governor Smith appointed Moses as president of the newly created Long Island BROOKLYN-BATTERY LINK State Park Commission. By 1925, Moses was also the chairman of the State Council of Parks. • In 1933, when Fiorello La Guardia, then mayor of New York City, invited Moses to head up the city's Parks Department and the Triborough Bridge Authority, Moses instituted a large building program(more than 1,700 projects—including a renovation of the Central Park), the construction of highways, tunnels and major POST-WAR CITY PLANNING bridges was also undertaken. • BY 1959, HE HAD OVERSEEN CONSTRUCTION OF 28,000 APARTMENT UNITS ON HUNDREDS OF ACRES OF LAND. -

New York State Principals New York State's High Schools, Middle Schools and Elementary Schools an Open Letter of Concern Regar

New York State Principals New York State’s High Schools, Middle Schools and Elementary Schools An Open Letter of Concern Regarding New York State’s APPR Legislation for the Evaluation of Teachers and Principals www.newyorkprincipals.org Over the past year, New York State has implemented dramatic changes to its schools. As building principals, we recognize that change is an essential component of school improvement. We continually examine best practices and pursue the most promising research-based school improvement strategies. We are very concerned, however, that at the state level change is being imposed in a rapid manner and without high-quality evidentiary support. Our students, teachers and communities deserve better. They deserve thoughtful reforms that will improve teaching and learning for all students. It is in this spirit that we write this letter, which sets forth our concerns and offers a path forward. We believe that it is our ethical obligation as principals to express our deep concerns about the recently implemented Annual Professional Performance Review (APPR) regulations. These regulations are seriously flawed, and our schools and students will bear the brunt of their poor design. Below we explain why we are opposed to APPR as it is presently structured. Background In May 2010, the New York State Legislature—in an effort to secure federal Race to the Top funds— approved an amendment to Educational Law 3012-c regarding the Annual Professional Performance Review (APPR) of teachers and principals. The new law states that beginning September 2011, all teachers and principals will receive a number from 0-100 to rate their performance.