A Palaeoecological Assessment of the Blanket Peat Surrounding the Source of the Severn, Plynlimon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I I I I I I I I I I I I

I I t INSTITIIIE OF HYDAOIOGY I Repolt No 30 January 1976 I (reprlnred t979) I I t TITEPTTYSIOGRAPHY, DEPOSI1S AND VE@TATION OF I T1IE PLYNLI IiIol.I CATqI!.,!ENTS I (A synthesls of published work aJld lnltj-al flndings) I by H D Newson I LIBRARY INSTITUTEOF }IYDBOLOGY I,IACLEANBUILD{NG I CROWMANSHGIFFORD \,1'ALLINGFORD,OXON t ox10888 I I I 8AS C l'toxo'c, ' 680Jir. CNIC:; I leo-i i. t I PROLOGUE Fromhigh Plynlimon\ shagqy side I Tfueenrearm in tfueedirections glide Tiad. nynlrnon satofl lolty heiStlt, I surveyedhis lands and w.rninS mighl from a throne.carvedbould€r, though mistytears hesaw rhe endingofhis years. I Hi lonScloak torn, now frded bare Ms tuggedby breezesthat spreadhis hair from hisforehead in a wild, grey mlne streaninglike some squall ot rain. I No sonwould ever take his realm no proudheir could w€ar his helrn hehad, but nowhir daughtersttuee I andthey must sh.rc his territory. t fron ThcSons af't bee Rive (1968'74) Afterascending the hill andpassjng over its top we wentdown on ih wesiernside and soon €me to a black I frightfulbog b€lween two hilh. Beyondthe bogand at some dinanceto the westofthe lwo hilk rosea brownmountain nol abruptly,but grrdu ly, arrdlooking more like wharrhe I Welshcall a rhiwor sloperhan a mynyddor n1ountain. 'i! "That,Sir." said my 8uide, the srandPtynlimon. Thelbuntains of theSevern and the Wyeare in clo3e I proximity10 elch orher.Thir ol the Rleidolslands somcwhal spanfrom bo1h.............._........... lion MH rvales(1862) I GeorgeBormu) ...............-...nrany high lti esand ptenrifuU Springs. -

The A5, A44, A55, A458, A470, A479, A483, A487, A489 and A494 Trunk

OFFERYNNAU STATUDOL WELSH CYMRU STATUTORY INSTRUMENT S 2019 Rhif (Cy. ) 2019 No. (W. ) TRAFFIG FFYRDD, CYMRU ROAD TRAFFIC, WALES Gorchymyn Cefnffyrdd yr A5, yr The A5, A44, A55, A458, A470, A44, yr A55, yr A458, yr A470, yr A479, A483, A487, A489 and A494 A479, yr A483, yr A487, yr A489 Trunk Roads (Various Locations in a’r A494 (Lleoliadau Amrywiol yng North and Mid Wales) (Temporary Ngogledd a Chanolbarth Cymru) Prohibition of Vehicles) Order (Gwahardd Cerbydau Dros Dro) 2019 2019 Gwnaed 15 Ebrill 2019 Made 15 April 2019 Yn dod i rym 25 Ebrill 2019 Coming into force 25 April 2019 Mae Gweinidogion Cymru, sef yr awdurdod traffig ar The Welsh Ministers, being the traffic authority for gyfer cefnffyrdd yr A5, yr A44, yr A55, yr A458, yr the A5, A44, A55, A458, A470, A479, A483, A487, A470, yr A479, yr A483, yr A487, yr A489 a’r A494, A489 and A494 trunk roads, are satisfied that traffic wedi eu bodloni y dylid gwahardd traffig ar ddarnau on specified lengths of the trunk roads should be penodedig o’r cefnffyrdd oherwydd y tebygolrwydd y prohibited due to the likelihood of danger to the byddai perygl i’r cyhoedd yn codi o ganlyniad i gludo public arising from the transportation of abnormal llwythi anwahanadwy annormal. indivisible loads. Mae Gweinidogion Cymru, felly, drwy arfer y pwerau The Welsh Ministers, therefore, in exercise of the a roddir iddynt gan adran 14(1) a (4) o Ddeddf powers conferred upon them by section 14(1) and (4) Rheoleiddio Traffig Ffyrdd 1984(1), yn gwneud y of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984(1), make this Gorchymyn hwn. -

THE ROLE of GRAZING ANIMALS and AGRICULTURE in the CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: Recognising Key Environmental and Economic Benefits Delivered by Agriculture in Wales’ Uplands

THE ROLE OF GRAZING ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURE IN THE CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: recognising key environmental and economic benefits delivered by agriculture in Wales’ uplands Author: Ieuan M. Joyce. May 2013 Report commissioned by the Farmers’ Union of Wales. Llys Amaeth,Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3BT Telephone: 01970 820820 Executive Summary This report examines the benefits derived from the natural environment of the Cambrian Mountains, how this environment has been influenced by grazing livestock and the condition of the natural environment in the area. The report then assesses the factors currently causing changes to the Cambrian Mountains environment and discusses how to maintain the benefits derived from this environment in the future. Key findings: The Cambrian Mountains are one of Wales’ most important areas for nature, with 17% of the land designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). They are home to and often a remaining stronghold of a range of species and habitats of principal importance for the conservation of biological diversity with many of these species and habitats distributed outside the formally designated areas. The natural environment is critical to the economy of the Cambrian Mountains: agriculture, forestry, tourism, water supply and renewable energy form the backbone of the local economy. A range of non-market ecosystem services such as carbon storage and water regulation provide additional benefit to wider society. Documentary evidence shows the Cambrian Mountains have been managed with extensively grazed livestock for at least 800 years, while the pollen record and archaeological evidence suggest this way of managing the land has been important in the area since the Bronze Age. -

Star Inn, by PUBLIC AUCTION

Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Estate Agents Established 1862 www.morrismarshall.co.uk BY PUBLIC AUCTION Star Inn, Dylife, Llanbrynmair, SY19 7BW Auction on Thursday 22nd September 2016 at Welshpool Livestock Market, Buttington, Welshpool, Powys SY21 8SR at 2pm • A noted former Public House/Restaurant/Bed & Breakfast. • Situated in a rural location, Machynlleth (10 miles) and Llanidloes (9½ miles). • Extensively refurbished and modernised to a high standard. • Lounge Bar, Dining Room/Restaurant, Meeting Room, Reception Room, Commercial Kitchen, Gents & Ladies Guide Price : £225,000 - £250,000 Llanidloes Office 01686 412567 [email protected] Foreword: The current owners purchased The Star Inn in 2013 and have carried out a complete scheme of refurbishment and modernisation. The property can be visited at www.starinndylife.co.uk. The Star Inn has been renowned in the past, and since 2013 has been open as a public house/bed & breakfast/restaurant. During the last few months the public bar and restaurant have been closed as the current owners are just taking in bed & breakfast visitors. The property offers prospective purchasers an Dining Room & Restaurant With Bar Servery opportunity to re-open The Star to its full with bench seating potential as a public house/restaurant and Store Room & Cellar bed & breakfast venture or to provide a Gentleman & Ladies WCs slower way of life as the current owners are operating. Second Reception Room With staircase leading off to the Letting Rooms on the first floor The property is located in rural Mid Wales being convenient to a number of villages and Meeting Room towns with the market towns of Llanidloes Commercial Kitchen (9½ miles) and Machynlleth (10 miles). -

Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, (GB 0210 ROBEVS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors- records-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors-records-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 5 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

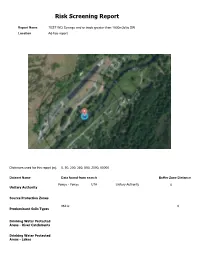

Risk Screening Report

Risk Screening Report Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Distances used for this report [m]: 0, 50, 200, 250, 500, 2000, 50000 Dataset Name Data found from search Buffer Zone Distance Powys - Powys UTA Unitary Authority 0 Unitary Authority Source Protection Zones 0611c 0 Predominant Soils Types Drinking Water Protected Areas - River Catchments Drinking Water Protected Areas - Lakes Groundwater Vulnerability Zones Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Groundwater Vulnerability MINOR MINOR_I MINOR_I1 0 Zones 1 National Park Main Rivers Scheduled Ancient Monuments LRC Priority & Protected Species: Coenagrion mercuriale (Southern Damselfly) Local Wildlife Sites Local Nature Reserves National Nature Reserves Protected Habitat: Aquifer fed water bodies Protected Habitat: Blanket bog Protected Habitat: Coastal Saltmarsh Protected Habitat: Coastal and Floodplain Grazing Marsh Protected Habitat: Fens Protected Habitat: Intertidal Mudflats Protected Habitat: Lowland raised bog Protected Habitat: Mudflats Protected Habitat: Reedbeds Report Name TEST WQ Sewage and or trade greater than 1000m3d to SW Location Ad-hoc report Protected Habitat: Reedbeds Protected Habitat: Wet Woodland LRC Priority & Protected Species: Anisus vorticulus (Little Whirlpool Ramshorn Snail) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Arvicola amphibius (Water vole) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Caecum armoricum (Lagoon Snail) LRC Priority & Protected Species: Cliorismia rustica -

Vebraalto.Com

Ty Capel Deildre, Van, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6NX Spectacular detached FIVE BEDROOM country residence with character and charm having extensive gardens in a choice rural location overlooking the Clywedog reservoir and surrounding open countryside. * Entrance Vestibule * Reception Hall * Kitchen * Lounge * Living Room * Conservatory * * Five Bedrooms (two with ensuite facilities) * Two further Bathrooms * Integral Garage * * Gardens and Grounds * Outstanding Views * EPC Rating 'tbc' * Offers in the region of £385,000 Freehold Agent's Remarks Bathroom Previously a Chapel, Ty Capel Deildref overlooks the beautiful scenery of the Clywedog Low level wc suite, pedestal wash hand basin, panelled bath. Electric towel radiator, shaver reservoir and is located in the heart of the mid Wales countryside. The property would benefit point. Part panelled walls, tiled floor, obscure window to side. Door to Inner Corridor. from some upgrading and re‐decorating but when done, this will be a extremely special and Bedroom 2 sought after dwelling. The views from each window are delightful and properties in a location Part panelled walls, radiator, window to side. Built‐in wardrobe with louvre doors. such as this rarely come on the the market so viewing is highly recommended. From Reception Hall a wood balustraded staircase leads to the First Floor. ACCOMMODATION comprises FIRST FLOOR Vestibule Half glazed uPVC entrance door with two secondary glazed windows either side. Open to Galleried Landing Part panelled walls. Radiator, Built in Cocktail Bar comprising single drainer sink unit with Reception Hall cupboard under and light over behind louvre doors. Part wood panelled walls, built‐in cupboards, understairs storage cupboard. Living Room Doors to: Fabulous room with open firegrate and cowl over set in to feature inglenook fireplace with Library stone hearth and surround with lintel over. -

Winter Service Plan 2018 / 2019

Winter Service Plan 2018 / 2019 Yn agored a blaengar - Open and enterprising www.powys.gov.uk The Winter Service Plan 2018/2019 was approved by Councillor Phyl Davies, Portfolio Holder for Highways on dd mmm 2018 Powys County Council Winter Service Delivery Plan 2018/2019 Contents Section A – Winter Service Policy Policy and Objectives Area Extent of Policy Statutory Requirements and Guidance Winter Risk Period Levels of Service Service Objectives for County Roads Service Delivery Responsibilities Role of Elected Members Community Involvement Liaison and Communication with Other Authorities and Agencies Decision Making and Management Decision Making in Extreme Weather Conditions The Service Information and Contact Details for the Public and Other Services Snow Clearance Discontinuity of Actions Salt/Grit Bins and Heaps Section B – Winter Service Operations Decision Making Operational Treatment Facilities, Plant, Vehicles and Equipment Salt and Other De-Icing Materials Treatment Requirements Including Spreading Rates Section C – Winter Service Snow Plan Appendices Appendix A – Information on Trunk Road Winter Services Appendix B – Priority Treatment Network Plan Appendix C – High Treatment Network Plan Appendix D – Secondary Treatment Network Plan Appendix E – Weather Station Location Plan Appendix F – Salt Storage Location Plan Appendix G – De-icing Rates of Spread Treatment Matrix Section A – Winter Service Policy Policy and Objectives Powys County Council aims to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

The Silurian Issue 1 June 2016

The Silurian Issue 1 June 2016 1 The Silurian Issue 1 June 2016 Contents 3 Origin and development of Welcome to the first edition of “T he ”. I hope you all enjoy the articles the club. Colin Humphrey. Silurian and I would like to thank all those who 5 Mineral Musings. Steve have contributed. I have tried to ensure a Moore. variety of topics as each of you will have some aspects of geology you prefer over 7 Metal Mines of Mid-Wales: others. Where are the lodes? Colin Humphrey. This is just the beginning and as with all 9 Fossils in the News. Sara publications, I expect it to change and Metcalf. morph over time into what you, the members, want it to be. 10 Fossil Focus: Trilobites. Sara Metcalf. Michele Becker 12 Geological Excursions: Excursion 1 Gilfach. Tony Thorp. 14 Excursion 2 Onny Valley. Michele Becker. 15 Bill's Rocks and Minerals. Fossil Wood: Mineral or Fossil? (or Both?). Bill Bagley. 17 Concretions and how they form. Tony Thorp. Mid-Wales Geology Club members. Photo ©Colin 20 Exploring the Building Humphrey. Stones of Llanidloes. Submissions Michele Becker. Submissions for the next issue by the beginning of October 2016 please. Please send articles for the magazine as either Cover Photo: Tan-y-Foel Quarry ©Richard plain text (.txt) or generic Word format (.doc), Becker and keep formatting to a minimum. Do not include photographs or illustrations in the All photographs and other illustrations are by the document. These should be sent as separate files author unless otherwise stated. saved as uncompressed JPEG files and sized to a All rights reserved. -

Visiting Wales on Expeditions

The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Visiting Wales on Expeditions Useful information Useful contacts Brecon Beacons: Eifion Jones, Rights of Way Officer, Brecon Information about the Beacons National Park Authority, Wild Country Areas: Plas y Ffynnon, Cambrian Way, Bronze and Silver expeditions are Brecon, Powys LD3 7HP. Tel: 01874 mainly outside of the Wild Country 624437. Areas. The expectation at Gold [email protected] level is that most will take place in beacons-npa.gov.uk/environment/ Wild Country. planning-access-and-row In Wales there are three Wild Snowdonia: Peter Rutherford, Country Areas, Snowdonia, Mid Access Officer at Snowdonia Wales and the Brecon Beacons. National Park. peter.rutherford@eryri. llyw.cymru snowdonia.gov.wales/looking- after/public-access You may also find the following contact useful when planning your visit: Elfyn Jones, Access & Conservation Officer Wales at British Mountaineering Council. [email protected] thebmc.co.uk. Brecon Beacons The Brecon Beacons is a mountain range in South Wales. The range forms the central section of the Brecon Beacons National Park, a designation which also encompasses ranges both to the east and the west of ‘the central Beacons’, it includes the Black Mountains to the east as well as the similarly named but quite distinct Black Mountain to the west. The Brecon Beacons range, comprises six main peaks: from west to east these are: Corn Du, 873 metres (2,864 ft), Pen y Fan, the highest peak, 886 metres (2,907 ft), Cribyn, 795 metres (2,608 ft), Fan y Bîg, 719 metres (2,359 ft), Bwlch y Ddwyallt, 754 metres (2,474 ft), and Waun Rydd 769 metres (2,523 ft). -

(Pecyn Cyhoeddus)Agenda Dogfen I/Ar Gyfer Pwyllgor Rheoli Datblygu, 19/05/2021 14:00

Pecyn Cyhoeddus Neuadd Cyngor Ceredigion, Penmorfa, Aberaeron, Ceredigion SA46 0PA ceredigion.gov.uk Dydd Iau, 13 Mai 2021 Annwyl Syr / Fadam Ysgrifennaf i’ch hysbysu y cynhelir Cyfarfod o Pwyllgor Rheoli Datblygu trwy We-Ddarlledu o Bell ar ddydd Mercher, 19 Mai 2021 am 2.00 pm i drafod y materion canlynol: 1. Ymddiheuriadau 2. Materion Personol 3. Datgelu buddiant personol a buddiant sy'n rhagfarnu 4. Cadarnhau Cofnodion y Cyfarfod a gynhaliwyd ar 10 Mawrth 2021 (Tudalennau 3 - 12) 5. Ystyried ceisiadau cynllunio a ohiriwyd mewn Cyfarfodydd blaenorol o’r Pwyllgor (Tudalennau 13 - 22) 6. Ceisiadau Statudol, Llywodraeth Leol, Hysbysebion a Datblygu (Tudalennau 23 - 58) 7. Ceisiadau Cynllunio y deliwyd â hwy o dan awdurdod dirprwyedig (Tudalennau 59 - 80) 8. Apeliadau (Tudalennau 81 - 82) 9. Unrhyw fater arall y penderfyna’r Cadeirydd fod arno angen sylw brys gan y Pwyllgor Darperir Gwasanaeth Cyfieithu ar y Pryd yn y cyfarfod hwn ac mae croeso i’r sawl a fydd yn bresennol ddefnyddio’r Gymraeg neu’r Saesneg yn y cyfarfod. Yn gywir Miss Lowri Edwards Swyddog Arweiniol Corfforaethol: Gwasanaethau Democrataidd At: Gadeirydd ac Aelodau Pwyllgor Rheoli Datblygu Weddill Aelodau’r Cyngor er gwybodaeth yn unig. 2 Tudalen 3 Eitem Agenda 4 Cofnodion cyfarfod y PWYLLGOR RHEOLI DATBLYGU a gynhaliwyd o bell drwy fideogynhadledd ddydd Mercher, 10 Mawrth 2021 Yn bresennol: y Cynghorwyr Lynford Thomas (Cadeirydd), John Adams-Lewis, Bryan Davies, Ceredig Davies, Gethin Davies, Meirion Davies, Ifan Davies, Odwyn Davies, Peter Davies MBE, Rhodri Davies, Dafydd Edwards, Rhodri Evans, Paul Hinge, Catherine Hughes, Gwyn James, Maldwyn Lewis, Lyndon Lloyd MBE, Gareth Lloyd, Dai Mason, Rowland Rees-Evans a Wyn Thomas.