Remembering Judge Sanders: Judicial Pragmatism in the Court of First and Last Resort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 27 Issue 2 Article 8 10-1989 Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963 Robert S. LaForte Richard Himmel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation LaForte, Robert S. and Himmel, Richard (1989) "Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 27 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol27/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 35 SARAH T. HUGHES, JOHN F. KENNEDY AND THE JOHNSON INAUGURALt 1963 by Robert S. LaForte and Richard Himmel The highpoint of Sarah Tilghman Hughes' judicial career was reached amid one of the great tragedies of recent Texas history, the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas by Lee Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963. In the afternoon of that day, aboard Air Force One, which was parked at Love Field, Judge Hughes swore in Lyndon Baines Johnson as the thirty-sixth president of the United States. In that brief moment of presidential history she became a national celebrity. Already prominent in Texas, this unhappy inaugural made her name known to multitudes of Americans, and although she had long been a force in modern feminism, she now became the first, and to date, only woman to administer the oath of office to an American chief executive. -

The Texas Observer SEPT. 30 1966

The Texas Observer SEPT. 30 1966 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c The Politics of HemisFair-- • And of San Antonio San Antonio HemisFair is what the president of San Antonio's chamber of commerce has mil- k, "this great excitement." But so far this bilingual city's 1968 international exposi- tion, "a half-world's fair," has caused more of the kind of excitement that terrifies 'the city's businessmen than the kind that de- lights them. They stand to lose all or part of the $7.5 million for which they have underwritten the fair in case it doesn't wind up in the black; they can fill fat treasure-pots with the long green if all , goes well. On the verge of 'becoming either civic patsies of commercial conquistadores, they are quick to anger and quick to com- promise, rash and 'suddenly politic. Hemis- Fair can make or break many of them. Therefore, HemisFair has entwined it- self all through the jungle of Texas 'poli- tics, whose elected practitioners know the private political meanings of public events and can foretell next year's lists of cam- paign contributions from this year's 'snarl- ups and alignments. HemisFair's exotic and colorful facade has been 'splattered again and again this year with charges of conflicts of interests, questions about the proper uses of public funds, political gueril- la warfare, and even, in the Senate for- eign relations committee, resentment of President Lyndon Johnson. It takes a pro- gram far more candid than HemisFair's ar- tistic brochures to follow the game. -

Andrew Pettit Morriss Texas A&M School of Innovation 1249 TAMU

Andrew Pettit Morriss Texas A&M School of Innovation 1249 TAMU 645 Lamar Street, Suite 110 (979) 862-6071 (o) [email protected] Employment Texas A&M University. Dean, School of Innovation, & Vice President for Entrepreneurship and Economic Development, August 2017 to date. Dean & Anthony G. Buzbee Dean’s Endowed Chair, School of Law. July 2014 to August 2017. University of Alabama. D. Paul Jones, Jr. & Charlene A. Jones Chairholder in Law and Professor of Business, August 2010 – June 2014. Visiting Professor of Law, October 2009. University of Illinois. H. Ross & Helen Workman Professor of Law, August 2006 – August 2010. Professor of Business, August 2006 – August 2010. Professor, Institute of Government and Public Affairs, August 2007 – July 2010. Case Western Reserve University Director, Center for Business Law & Regulation, 2003- 2007. Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, 2000 - 2003. Galen J. Roush Professor of Business Law and Regulation, 2000 - 2007. Professor of Law and Associate Professor of Economics, 1998 - 2000. Associate Professor of Law and Associate Professor of Economics, 1995 - 1998. Assistant Professor of Law and Assistant Professor of Economics, 1992 - 1995. Cayman Financial Review Editorial Board. Editorial Board Chair. Nov. 2009 – April 2017. Member. Nov. 2008 – April 2017. Property & Environment Research Center, Bozeman, Montana. Senior Fellow. 1999 – present. Visiting Scholar. Fall 1999. Reason Foundation. Senior Fellow, Fall 2012 – present. Morriss Vita, page 2 Research Scholar, Regulatory Studies Center, George Washington University, 2010 – present. Senior Scholar, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2005 – present. Research Fellow, NYU Center for Labor and Employment Law, 2001 – present. Senior Fellow, Institute for Energy Research, Houston, Texas, 2006 – present. -

Judge Barefoot Sanders Law Magnet School

U.S. Department of Education 2012 National Blue Ribbon Schools Program A Public School - 12TX22 School Type (Public Schools): (Check all that apply, if any) Charter Title 1 Magnet Choice Name of Principal: Mr. Anthony Palagonia Official School Name: Judge Barefoot Sanders Law Magnet School School Mailing Address: 1201 E. Eighth Street Dallas, TX 75203-2564 County: Dallas County State School Code Number*: 057905038 Telephone: (972) 925-5950 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (972) 925-6010 Web site/URL: http://www.dallasisd.org/ I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 2 (Part I - Eligibility Certification), and certify that to the best of my knowledge all information is accurate. _________________________________________________________ Date _____________________ (Principal’s Signature) Name of Superintendent*: Mr. Alan King Superintendent e-mail: [email protected] District Name: Dallas ISD District Phone: (972) 925-3700 I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 2 (Part I - Eligibility Certification), and certify that to the best of my knowledge it is accurate. _________________________________________________________ Date _____________________ (Superintendent’s Signature) Name of School Board President/Chairperson: Dr. Lew Blackburn I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 2 (Part I - Eligibility Certification), and certify that to the best of my knowledge -

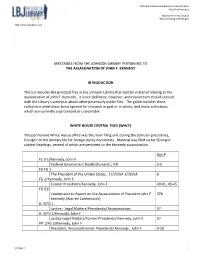

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

CISD Welcomes New Director of Human Resources

Serving the City of River Oaks 81st Year No. 22 • 817-246-2473 • 7820 Wyatt Drive, White Settlement, Texas 76108 • suburban-newspapers.com • June 3, 2021 From Castleberry ISD From Castleberry ISD CISD Welcomes New Director Signs of Things to Come of Human Resources Castleberry ISD would like to wel - come Dr. Myrna Blanchard as the new Director of Human Resources. Dr. Blanchard comes to us from Fort Worth, most The Class of 2021 is the second class to graduate from high recently serving as a school during a global pandemic, and as a tribute CISD has placed campus principal. signs in front of Castleberry High School honoring each Senior. She began her These 232 candidates for graduation are from both Castleberry educational career High School and REACH High School and each student will 20 years ago as a receive an identical sign for themselves. Bilingual/ESL The perseverance and determination of these students to grad - teacher. She has uate during this unusual time in history is truly a sign of great also taught as an things to come for each of them. adjunct professor and instructor at both Texas Wesleyan University and the University of Texas at Arlington. From the City of River Oaks Dr. Blanchard earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Educational Leadership from the University of North Texas, a Master of Bilingual Education degree from Texas Wesleyan Sign Up for Code Red Alerts University, and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of River Oaks residents can keep informed through the Code Red Texas at Arlington. -

I Tnite Tate

No. OFFICE OF THE CLL~K i tnite tate DR. HERMAN SMITH, Petitioner, Vo KAREN JO BARROW, Respondent. On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI THOMAS P. BRANDT Counsel of Record JOSHUA A. SKINNER ROBERT FUGATE FANNING HARPER ~ MARTINSON, P.C. 4849 Greenville Ave., Suite 1300 Dallas, Texas 75206 (214) 369-1300 Attorneys for Petitioner COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. When a public school teacher, who is denied a promotion to an administrative position in the public school district because she chooses to educate her children in a competing private school, asserts a parental rights claim against the public school super- intendent based on his failure to promote her, is that Fourteenth Amendment claim subject to rational basis scrutiny pursuant to Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972), or is it subject to a heightened level of scrutiny as held by the Fifth Circuit? 2. Whether it is appropriate, within the current framework of qualified immunity, to apply the law of the case doctrine in such a way as to preclude a public school superintendent from asserting the defense of qualified immunity, when the "law of the case" was based on facts which were assumed prior to trial and the superintendent’s qualified immunity defense is based on the actual facts which were found at trial. 3. Whether the Fifth Circuit’s approach to Smith’s Rule 68 offer of judgment and interrelated legal issues regarding attorney’s fees improperly serves to encourage wasteful litigation instead of encouraging the "just, speedy and inexpensive resolu- tion of civil disputes." ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Including the parties named in the caption of this Petition, the parties to the proceeding in the court whose judgment is sought to be reviewed are: Dr. -

by Harrison E. Livingstone C 1996 •• the Place of Origin Or

/M, "Barefoot Sanders, Ramsey Clark, and the Dallas Invasion of Washington: The Later Coverup of the Medical Evidence." , By Harrison E. Livingstone c 1996_ •• The place of origin or longtime residence of figures in the JFK case may or may not be significant. Texans are suspect due to the probabilities that the conspiracy had its origin in Texas. There is a pattern of not just Texans moving to Washington for high positions in the Johnson administration after the assassination of John Kennedy, but those from Dallas itself. I'm not proposing guilt by association with Texas, but what can we read from this when there was enough money in Dallas/Fort Worth to buy or coerce anyone? Johnson's ranch was near Austin, yet his primary support before the assassination had its base in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, both politically and financially, though not with the voters. One of his chief political backers in Dallas was United States Attorney Barefoot Sanders. Barefoot (a family name) Sanders was credentialed as a liberal Democrat, and if anything, acted as a brake on the more conservative and radical elements in his city. Sanders drove Judge Sarah Hughes to Love Field to go to Kennedy's funeral in Washington. She had sworn in Johnson on the plane shortly after the assassination. Soon more than 90 witnesses were making statements to the Warren Commission in Dallas, and many of these testified in Sander's office. Some complained that their testimony was altered. Sanders still in Dallas, began playing a rdle in the investigation early. -

The Storied Third Branch

The Storied Third Branch A Rich Tradition of Honorable Service Seen Through the Eyes of Judges OCTOBER 2012 CENTER FOR JUDICIAL STUDIES Irving Goldberg “Remembering Irving Goldberg” By Diane P. Wood, Federal Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit The basic facts about Irving L. Goldberg, who served for 31 years on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, are easy to summarize. Born in Port Arthur, Texas, in 1906, he received his B.A. from the University of Texas at Austin in 1926 and his LLB from Harvard Law School in 1929. Upon his graduation, he practiced in several cities in Texas until World War II broke out. Finding himself in Washington, D.C., as a Navy Lieutenant, Goldberg worked with the Committee on Naval Affairs, on which then-Congressman Lyndon Johnson was serving. Another Texan was also serving in Congress at that time – the legendary Sam Rayburn, who became Speaker of the House in 1940. As Judge Goldberg told the story over coffee and donuts, “Lyndon,” “Sam,” and Irving often carpooled around Washington during those days. Their friendship was cemented. After the war, Goldberg returned to Texas, where he settled in Dallas and with Robert Strauss and others formed the law firm that today is known as Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP. Although his practice was not limited to tax matters, he particularly enjoyed those cases. One of his more notable clients was – once again – Lyndon Johnson. This is how Goldberg came to play a small but important part in the tragic events of November 22, 1963 – a story that his many law clerks heard over morning coffee and that Lawrence J. -

Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963 Robert S

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 27 | Issue 2 Article 8 10-1989 Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963 Robert S. LaForte Richard Himmel Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation LaForte, Robert S. and Himmel, Richard (1989) "Sarah T. Hughes, John F. Kennedy and the Johnson Inaugural, 1963," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 27: Iss. 2, Article 8. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol27/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 35 SARAH T. HUGHES, JOHN F. KENNEDY AND THE JOHNSON INAUGURALt 1963 by Robert S. LaForte and Richard Himmel The highpoint of Sarah Tilghman Hughes' judicial career was reached amid one of the great tragedies of recent Texas history, the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas by Lee Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963. In the afternoon of that day, aboard Air Force One, which was parked at Love Field, Judge Hughes swore in Lyndon Baines Johnson as the thirty-sixth president of the United States. In that brief moment of presidential history she became a national celebrity. Already prominent in Texas, this unhappy inaugural made her name known to multitudes of Americans, and although she had long been a force in modern feminism, she now became the first, and to date, only woman to administer the oath of office to an American chief executive. -

June 3, 2021 from the Sports Desk with John English Player Feature: BMHS Volleyball’S Madison Sorrell

81st Year No. 22 • 817-246-2473 • 7820 Wyatt Drive, White Settlement, Texas 76108 • suburban-newspapers.com • June 3, 2021 From the Sports Desk with John English Player Feature: BMHS Volleyball’s Madison Sorrell ior will be one of Benbrook's main producers. “My legacy that I would like to leave is “She leads both by being a senior and her that I contributed to the success of the teams I overall presence,” Davies said. “She wants to played with and that I made a positive contri - win and helps push her teammates to fight just bution to the team,” Sorrell said. “Also, I as hard. I think she has the potential to easily would like to inspire others to play their best. grab a district superlative. It will just be a mat - It is my dream to be a student-athlete at the ter of which one we want to fight for with her. college level.” Between her massive swing and her height and Davies said her major objective for Sorrell blocking, she’ll definitely be a major part of this off-season is focusing on the mentality it our future success.” takes to step into that leadership position. Sorrell, 17, said overall, she is pretty satis - “We are in a very big re-build, and she will fied with what the Lady Cats accomplished in need to be that player all the others look to and 2020. want to emulate,” Davies said. “We will also “It was a challenging year due to COVID,” be working on our speed on the defensive side. -

Evidence & Investigations

Evidence & Investigations Books - Articles - Videos - Collections - Oral Histories - YouTube - Websites Visit our Library Catalog for complete list of books, magazines, and videos. Books Bloomgarden, Henry S. The Gun: A "Biography" of the Gun that Killed John F. Kennedy. New York: Bantam Books, 1975. Bonner, Judy Whitson. Investigation of a Homicide; the Murder of John F. Kennedy. Droke House, 1969. Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History: the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. Chambers, G. Paul. Head Shot: the Science behind the John F. Kennedy Assassination. New York: Prometheus Books, 2010. Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications. Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1982. Cutler, Robert Bradley. Two Flightpaths: Evidence of Conspiracy. Massachusetts: Minutemen Press, 1988. Curry, Jesse E. Retired Dallas Police Chief, Jesse Curry, Reveals His Personal JFK Assassination File. Dallas: 1969. Garrison, Jim. On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy. New York: Sheridan Square Press, 1988. Horn, Douglas P. Inside the Assassination Records Review Board: The U.S. Government's Final Attempt to Reconcile the Conflicting Medical Evidence in the Assassination of JFK. Falls Church, VA: 2009. Marcus, Raymond. The HSCA, the Zapruder Film and the Single-Bullet Theory. [S.l.]: Raymond Marcus, 1992. Meagher, Sylvia and Gary Owens. Master Index to the J.F.K. Assassination Investigations the reports and supporting volumes of the House Select Committee on Assassinations and the Warren Commission. New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1980. Rockefeller, Nelson A. Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States.