Binder Beatrice Mary 1959 Sec.Pdf (14.42Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Example Response to a Real Horary Question

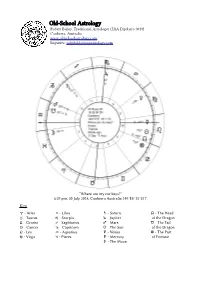

Old-School Astrology Robert Bailey, Traditional Astrologer (FAA DipAstro 2018) Canberra, Australia www.oldschoolastrology.com Inquiries: [email protected] “Where are my car keys?” 6:29 pm, 30 July 2018, Canberra Australia 149ºE8' 35ºS17' Key ♈ - Aries ♎ - Libra * - Saturn + - The Head ♉ - Taurus ♏ - Scorpio & - Jupiter of the Dragon ♊ - Gemini ♐ - Sagitarius ( - Mars , - The Tail ♋ - Cancer ♑ - Capricorn ! - The Sun of the Dragon ♌ - Leo ♒ - Aquarius & - Venus B - The Part ♍ - Virgo ♓ - Pisces $ - Mercury of Fortune # - The Moon Signifcators. Aquarius rises, so you are signified by Saturn, the Lord of Aquarius. Saturn is in the 12th house at 3° Capricorn. He is dignified by domicile, but also retrograde and in a cadent house. The keys are signified by the 2nd house, Pisces. The Lord of Pisces is Jupiter, so Jupiter signifies your keys in this chart. Jupiter is in the 10th house at 13° Scorpio. He is peregrine and moving a bit slow (4’ per day) but otherwise in a good condition – and he is conjunct the Midheaven. The Moon is in the 2nd house at 4° Pisces. She is peregrine, moving slow-ish (12°03’ per day) and is placed in a succedent house. The Moon separates from a sextile aspect with Saturn and applies to a trine with Jupiter. The Sun separates from an opposition with Mars and applies to a square aspect with Jupiter. Note also Mercury, the natural significator of keys, is retrograde and placed in the 7th house conjunct the DSC at 22° Leo, where he has dignity by term. Analysis. The Lord of the 2nd house Jupiter signifies your keys. Jupiter is in the 10th house, suggesting the keys are at your place of work. -

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St

A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St. Louis Mercantile Library The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association Major-General Ethan Allen Hitchcock (1798 - 1870) A GUIDE TO THE ETHAN ALLEN HITCHCOCK COLLECTION OF THE ST. LOUIS MERCANTILE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION A collective effort produced by the NEH Project Staff of the St. Louis Mercantile Library Copyright (c) 1989 St. Louis Mercantile Library Association St. Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Staff................................ i Foreword and Acknowledgments................. 1 A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Collection. .. 6 Aoppendix. 109 NEH PROJECT STAFF Project Director: John Neal Hoover* Archivist: Ann Morris, 1987-1989 Archivist: Betsy B. Stoll, 1989 Consultant: Louisa Bowen Typist: ' Betsy B. Stoll This project was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities * Charles F. Bryan, Jr. Ph.D., Executive Director of the Mercantile Library 1986-1988; Jerrold L. Brooks, Ph.D. Executive Director of the Mercantile Library, 1989; John Neal Hoover, MA, MLS, Acting Librarian, 1988, 1989, during the period funded by NEH as Project Director -i- FOREWORD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: For over one thousand years, the field of alchemy gathered to it strands of religion, the occult, chemistry, pure sciences, astrology and magic into a broad general philosophical world view which was, quite apart from the stereotypical view of the charlatan gold maker, concerned with the forming of a basis of knowledge on all aspects of life's mysteries. As late as the early nineteenth century, when many of the modern fields of the true sciences of mind and matter were young and undeveloped, alchemy was a beacon for many people looking for a philosophical basis to the better understanding of life--to the basic religious and philosophical truths. -

Renaissance Man, Series One, Part 2

Renaissance Man, Series One, Part 2 RENAISSANCE MAN: THE RECONSTRUCTED LIBRARIES OF EUROPEAN SCHOLARS, 1450-1700 Series One: The Books and Manuscripts of John Dee, 1527-1608 Part 2: John Dee's Manuscripts from Corpus Christi College, Oxford Contents listing EDITORIAL PREFACE PUBLISHER'S NOTE CONTENTS OF REELS DETAILED LISTING Renaissance Man, Series One, Part 2 Editorial Preface by Dr Julian Roberts Research on John Dee (1527-1609) is gradually showing him to be one of the most interesting and complex figures of the late English renaissance. Although he was long regarded – for example in the Dictionary of National Biography – as alternately a charlatan and a dupe, he was revealed by E G R Taylor in 1930 as the teacher of the most important Elizabethan navigators. Research since then has underlined his role in the teaching of mathematics and astronomy, in astrology, alchemy, British antiquities, hermeticism, cabala and occultism, and, posthumously, in the Rosicrucian “movement” that swept Europe in the second and third decades of the seventeenth century. Dee thus stood, in the middle of the sixteenth century, at the watershed between magic and science, looking back at one and forward to the other. Central to all these interests was a great library, the largest that had ever been built up by one man in England. Dee’s omnivorous reading (demonstrated by his characteristic annotation) and the availability of his library to others fed many of the intellectual streams of Elizabethan England, and he was well known to Continental scholars, even before his ultimately disastrous visit to eastern Europe in 1583-89. -

Trans. Greek Thot Handout

11/14/19 TRANSMISSION OF GREEK THOUGHT TO THE WEST PLATO & NEOPLATONISM Chalcidius (late 3rd-early 4th cent. Christian exegete): incomplete translation & commentary of Timeaus Henricus Aristippus in Sicily (12th c.): translated the Meno and Phaedo Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370-1444/Florence) translated a selection of Plato’s dialogues (from Greek to Latin). Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499/Florence): 1st complete translation into Latin of Plato’s works (publ. 1496), and translation of Plotinus’s Enneads into Latin (1492). Neoplatonic thought was transmitted in the following: (a) Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (written 524, in prison) (b) Macrobius’ Commentary on Cicero’s Dream of Scipio (written c. 400 CE). (c) Pseudo-Dionysius. A collection of writings attributed to Dionysius the Aeropagite (see Acts 17:34), but 19th century scholarship determined to be written c. 500 by a disciple of Proclus, held considerable authority throughout the middle ages and was a Christian Neoplatonism. (d) Theologica Aristotelis: this summary of Books 4-6 of Plotinus’s Enneads had been wrongly attributed to Aristotle (until 13th century) (e) Liber de Causis: this work based on Proclus’s Elements of Theology was wrongly attributed to Aristotle (until 13th century). ARISTOTLE Victorinus (4th century): Latin translations of Aristotle’s Categories and De interpretatione, as well as of Porphyry’s Isagoge. Boethius (470-524/Padua?): translated the entire Organon and wrote commentaries on all but the Posterior Analytics), as well as a translation of Porphyry’s introduction (Isagoge) to the Categories, but only De Interp. and Categories were readily available until 12th century. James of Venice (c.1128): translated Posterior Analytics; with the rediscovery of other translations by Boethius, this completed the Organon. -

Alchemy Archive Reference

Alchemy Archive Reference 080 (MARC-21) 001 856 245 100 264a 264b 264c 337 008 520 561 037/541 500 700 506 506/357 005 082/084 521/526 (RDA) 2.3.2 19.2 2.8.2 2.8.4 2.8.6 3.19.2 6.11 7.10 5.6.1 22.3/5.6.2 4.3 7.3 5.4 5.4 4.5 Ownership and Date of Alternative Target UDC Nr Filename Title Author Place Publisher Date File Lang. Summary of the content Custodial Source Rev. Description Note Contributor Access Notes on Access Entry UDC-IG Audience History 000 SCIENCE AND KNOWLEDGE. ORGANIZATION. INFORMATION. DOCUMENTATION. LIBRARIANSHIP. INSTITUTIONS. PUBLICATIONS 000.000 Prolegomena. Fundamentals of knowledge and culture. Propaedeutics 001.000 Science and knowledge in general. Organization of intellectual work 001.100 Concepts of science Alchemyand knowledge 001.101 Knowledge 001.102 Information 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification1961 Universal Decimal Classification 1961 pdf en A complete outline of the Universal Decimal Classification 1961, third edition 1 This third edition of the UDC is the last version (as far as I know) that still includes alchemy in Moreh 2018-06-04 R 1961 its index. It is a useful reference documents when it comes to the folder structure of the 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification2017 Universal Decimal Classification 2017 pdf en The English version of the UDC Online is a complete standard edition of the scheme on the Web http://www.udcc.org 1 ThisArchive. is not an official document but something that was compiled from the UDC online. Moreh 2018-06-04 R 2017 with over 70,000 classes extended with more than 11,000 records of historical UDC data (cancelled numbers). -

Curriculum Vitae Thomas E

Curriculum vitae Thomas E. Burman Medieval Institute / Department of History University of Notre Dame 574-631-6603 [email protected] Citizenship: United States of America EDUCATION UNIVERSITY EDUCATION B. A. Whitman College (Walla Walla, WA), May 1984, with majors in History and Spanish Language and Literature. M. A. in Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, November, 1986. M. L. S. (Licentiate of Mediaeval Studies), sectio historica, from the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (Toronto), May 1989. Thesis title: “The Influence of the Apology of al-Kindī and Contrarietas alfolica on Lull’s Late Religious Polemics, 1305-1313.” Ph.D. in Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, November, 1991. Major field of study: Medieval Spanish Intellectual and Social History. Minor Fields: 1] Middle East and Islamic Studies; 2] Latin Paleography and the Editing of Latin Texts. Dissertation title: “Spain’s Arab Christians and Islam, 1050-1220: The Text of Liber denudationis (alias Contrarietas alfolica) and its Intellectual Milieu.” Dissertation supervisor: J. N. Hillgarth, Professor of History, University of Toronto, and Senior Fellow, the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, Toronto. LANgUAgES Advanced Conversational and Reading Knowledge of Spanish. Advanced Reading Knowledge of Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, and French. Limited Conversational Ability in Arabic and French. Reading Knowledge of german, Italian, Portuguese, Catalan, Aramaic PROFESSIONAL HISTORY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor of History, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, August, 1991 - July, 1997. On leave from the University of Tennessee as Visiting Assistant Professor and Rockefeller Research Fellow at the Center for the Study of Islamic Societies and Civilizations, Washington University, St. Louis, 1992-93. Associate Professor History, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, August, 1997 – July 2008. -

Latin Averroes Translations of the First Half of the Thirteenth Century

D.N. Hasse 1 Latin Averroes Translations of the First Half of the Thirteenth Century Dag Nikolaus Hasse (Würzburg)1 Palermo is a particularly appropriate place for delivering a paper about Latin translations of Averroes in the first half of the thirteenth century. Michael Scot and William of Luna, two of the translators, were associated with the court of the Hohenstaufen in Sicily and Southern Italy. Michael Scot moved to Italy around 1220. He was coming from Toledo, where he had already translated at least two major works from Arabic: the astronomy of al-BitrÚºÍ and the 19 books on animals by Aristotle. In Italy, he dedicated the translation of Avicenna’s book on animals to Frederick II Hohenstaufen, and he mentions that two books of his own were commissioned by Frederick: the Liber introductorius and the commentary on the Sphere of Sacrobosco. He refers to himself as astrologus Frederici. His Averroes translation, however, the Long Commentary on De caelo, is dedicated to the French cleric Étienne de Provins, who had close ties to the papal court. It is important to remember that Michael Scot himself, the canon of the cathedral of Toledo, was not only associated with the Hohenstaufen, but also with the papal court.2 William of Luna, the other translator, was working apud Neapolim, in the area of Naples. It seems likely that William of Luna was associated to Manfred of Hohenstaufen, ruler of Sicily.3 Sicily therefore is a good place for an attempt to say something new about Michael Scot and William of Luna. In this artic le, I shall try to do this by studying particles: small words used by translators. -

Shahed Ahmed Power

GANDHI DEEP ECOLOGY: -4 Experiencing thg Nonhuman Environment Shahed Ahmed Power Ph. D. Thesis Environmental Resources Unit, University of Salford 1990 r Dedicated to all my friends and to the memory of Sugata Dasgupta (1926 - 1984) iii Contents Page List of Maps iii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations vi Abstract viii Introduction 1 The psychological background 4 Chapter I: GANDHI: The Early Years 12 Chapter II: GANDHI: South Africa 27 Chapter III: GANDHI: India 1915 - 1931 59 Chapter IV: GANDHI: India 1931 - 1948 93 Chapter V: THOREAU: 1817 - 1862 120 Chapter VI: Background to Deep Ecology 153 John Muir (1838 - 1914) 154 Richard Jefferies (1848 - 1887) 168 Mary Austin (1868 - 1934) 172 Aldo Leopold (1886 - 1948) 174 Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889 - 1982) 177 Indigenous People: 178 (i) Amerindian 179 (ii) North-East India 184 Chapter VII: ARNE NAESS 191 Chapter VIII: Summary & Synthesis 201 Bibliography 211 Appendix 233 List of Maps: Map of Indian Subcontinent - between pages 58 and 59 Map of North-East India - between pages 184 and 185 iv Acknowledgements: Though he is not mentioned in the main body of the text, I have-been greatly influenced by the writings and life of the American religious writer Thomas Merton (1915 - 1968). Born in Prades, France, Thomas Merton grew up in France, England and the United States. In 1941 he entered the Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, Kentucky, where he is now buried, though he died in Bangkok. The later Merton especially was a guide to much of my reading in the 1970s. For many years now I have treasured a copy of Merton's own selection from the writings of Gandhi on Non-Violence (Gandhi, 1965), as well as a collection of his essays on peace (Merton, 1976). -

Dangerous Vaccines - All the Proof in the World

DANGEROUS VACCINES - ALL THE PROOF IN THE WORLD Chapters: 1. No. 1 Cause Of All Health Problems - Our Health Care System 2. A Pharmacist Questions Vaccines 3. The Myth of Polio & Smallpox Eradication 4. The Myth People Are Living Longer 5. AIDS Drugs Do More Harm Than Good 6. Babies Dying In Vaccine Trials 7. How the MMR and Measles Vaccines Endanger Your Child's Health 8. Doctor Calls Chicken Pox Vaccine Deaths "Reassuring" 9. Deaths & Adverse Reactions from Vaccines 10. Reports on Vaccine Dangers 11. Government Payouts to Vaccine Damaged Victims 12. Doctors Believe Their Technology Is Superior to Mother Nature's 13. The Tamiflu Scam / Dr. Mercola's Total Health Program 14. Scary Medicine: Exposing The Dark Side of Vaccines 15. Extensive Research on Vaccines Proves the Dangers 16. Biased Reporting: A Vaccination Case Study 17. Mercury Toxicity and Autism 18. Horrors of Vaccination Exposed and Illustrated 19. Quotes On Vaccines By Health Care Experts 20. Vaccination Statistics 21. What's Really In Vaccines? Proof of MSG, Formaldehyde, Aluminum and Mercury 22. Additional Vaccine Facts 23. The Flu - Facts Show Different Picture 24. Vaccine Blamed for the Worst Flu Season in Four Years 25. Why Vaccinations Harm Children: Health Experts Sound Off 26. The Flawed Theory Behind Vaccinations & Why MMR Jabs Are Dangerous 27. Waking Up To Vaccine Dangers 28. Pet Vaccine Myths Debunked 29. Questions To Ask Your Physician or Vaccine Advocate 30. Universal Immunization — Medical Miracle or Masterful Mirage 31. Physician’s Warranty of Vaccine Safety 32. The Death of Medicine: An Open Letter to Allopathic Physicians 33. -

Electional Astrology By

ELECTIONAL ASTROLOGY BY Vivian E. Robson, B.Sc. Author of A Student’s Textbook of Astrology, The Radix System, Astrology & Sex, Etc.,etc. Republished by Canopus Publications Box 774 Kingston, Tasmania 7051 Australia 1 All rights reserved © Canopus Publications This Publication has been reproduced from the original text in the interest of preserving and disseminating old Astrological texts. This version may not be reproduced or transmitted by any means electronic or mechanical or recorded in any form including photocopying or scanning or by any storage or retrieval system. It is available free of charge for personal use and may not be used for reselling or any other commercial purposes. To do so is in violation of copyright law. The text can be printed for personal use on A4 paper. The publishers and editor have taken all measures to ensure this publication is an accurate reproduction of the original but cannot guarantee it to be free of typographical errors. 2 PREFACE In issuing this volume I feel that I am filling a serious gap in astrological literature, for no book on Electional Astrology has ever before been published, and the subject is one that is almost unknown to the great majority of students. From ancient times up to the seventeenth century Electional Astrology in common with all the other branches of the subject received a good deal of attention, and it is a matter for surprise that it has not shared in the present revival of interest in Astrology, considering the extreme popularity and usefulness of the matters with which it deals.