The Polish Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r33q03k Author Eaton, Nicole M. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). -

The Role of Maritime Education and Training of Young Adults in Creating a Strategic Model for the Management of a Public Diplomacy Project

the International Journal Volume 13 on Marine Navigation Number 2 http://www.transnav.eu and Safety of Sea Transportation June 2019 DOI: 10.12716/1001.13.02.16 The Role of Maritime Education and Training of Young Adults in Creating a Strategic Model for the Management of a Public Diplomacy Project A. Czarnecka & K. Muszyńska Gdynia Maritime University, Gdynia, Poland ABSTRACT: The article focuses on the issues of maritime education and training of young adults as a tool of public diplomacy. In the first part, the authors present a contemporary approach to the tools and tasks of public diplomacy used for strengthening the image of the state. 1 INTRODUCTION The link for the marketing message of the Independence Sail was the young people Public diplomacy is a form of international participating in the project including the GMU 1 communication. It is perceived as the most important students from Navigation Department taking their tool of soft power ‐ an indispensable tool these days obligatory seamanship training. The design of the for building the power of the state and its position in training program for all the participants of the the international environment [Ociepka B. 2013]. It is Independence Sail, allowed soft communication of used in parallel with the national branding so they essential values to improve the country image such as complement each other and make a modern tool for patriotism, unity, identity, without intrusive building the Stateʹs image in a long term. advertising. From the point of view of public diplomacy, the centenary of the restoration of Poland’s independence can be perceived as a vehicle for values that should be 2 ORGANIZATION AND IDEA BEHAIND THE communicated at home and abroad. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

1781 - 1941 a Walk in the Shadow of Our History by Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington

1781 - 1941 A Walk in the Shadow of Our History By Alfred Opp, Vancouver, British Columbia Edited by Connie Dahlke, Walla Walla, Washington For centuries, Europe was a hornet's nest - one poke at it and everyone got stung. Our ancestors were in the thick of it. They were the ones who suffered through the constant upheavals that tore Europe apart. While the history books tell the broad story, they can't begin to tell the individual stories of all those who lived through those tough times. And often-times, the people at the local level had no clue as to the reasons for the turmoil nor how to get away from it. People in the 18th century were duped just as we were in 1940 when we were promised a place in the Fatherland to call home. My ancestor Konrad Link went with his parents from South Germany to East Prussia”Poland in 1781. Poland as a nation had been squeezed out of existence by Austria, Russia and Prussia. The area to which the Link family migrated was then considered part of their homeland - Germany. At that time, most of northern Germany was called Prussia. The river Weichsel “Vitsula” divided the newly enlarged region of Prussia into West Prussia and East Prussia. The Prussian Kaiser followed the plan of bringing new settlers into the territory to create a culture and society that would be more productive and successful. The plan worked well for some time. Then Napoleon began marching against his neighbors with the goal of controlling all of Europe. -

For the SGGEE Convention July 29

For the SGGEE Convention July 29 - 31, 2016 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada 1 2 Background to the Geography It is the continent of Europe where many of our ancestors, particularly from 1840 onward originated. These ancestors boarded ships to make a perilous voyage to unknown lands far off across large oceans. Now, you may be wondering why one should know how the map of Europe evolved during the years 1773 to 2014. The first reason to study the manner in which maps changed is that many of our ancestors migrated from somewhere. Also, through time, the borders on the map of Europe including those containing the places where our ancestors once lived have experienced significant changes. In many cases, these changes as well as the history that led to them, may help to establish and even explain why our ancestors moved when they did. When we know these changes to the map, we are better able to determine what the sources of family information in that place of origin may be, where we may search for them, and even how far back we may reasonably expect to find them. A map of the travels of German people lets me illustrate why it has become necessary to acquaint yourself with the history and the changing borders of Eastern Europe. Genealogy in this large area becomes much more difficult without this knowledge. (See map at https://s3.amazonaws.com/ps-services-us-east-1- 914248642252/s3/research-wiki-elasticsearch-prod-s3bucket/images/thumb/a/a9/ Germans_in_Eastern_Europe5.png/645px-Germans_in_Eastern_Europe5.png) In my case, the Hamburg Passenger Lists gave me the name of the village of origin of my grandmother, her parents, and her siblings. -

Poles Under German Occupation the Situation and Attitudes of Poles During the German Occupation

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/poles-under-german-occu/15596,Poles-under-German-Occupation.html 2021-09-25, 22:48 Poles under German Occupation The Situation and Attitudes of Poles during the German Occupation The Polish population found itself in a very difficult situation during the very first days of the war, both in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in The General Government. The policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Executions, resettlements, arrests, deportations to camps, and street round-ups were a constant element of the everyday life of Poles during the war. Initially the policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Food rationing was imposed in cities and towns, with food coupons covering about one-third of a person’s daily needs. Levies — obligatory, regular deliveries of selected produce — were introduced in the countryside. Farmers who failed to deliver their levy were subject to severe repressions, including the death penalty. Devaluation and difficulty with finding employment were the reason for most Poles’ poverty and for the everyday problems in obtaining basic products. The occupier also limited access to healthcare. The birthrate fell dramatically while the incidence of infectious diseases increased significantly. -

I~ ~ Iii 1 Ml 11~

, / -(t POLIUSH@, - THE NEW GERMAN BODanER I~ ~ IIi 1 Ml 11~ By Stefan Arski PROPERTY OF INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS 214 CALIFORNIA HALL T HE NE W POLISH-GERMAN B O R D E R SAFEGUARD OF PEACE By Stefan Arski 1947 POLISH EMBASSY WASHINGTON, D. C. POLAND'S NEW BOUNDARIES a\ @ TEDEN ;AKlajped T5ONRHOLM C A a < nia , (Kbn i9sberq) Ko 0 N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- K~~~towicealst Pr~~ue J~~'~2ir~~cou Shaded area: former German territories, east of the Oder and Neisse frontier, assigned to Poland at Potsdam by the three great Allied powers: the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain. The whole area comprising 39,000 square miles has already been settled by Poles. [ 2 ] C O N T E N T S Springboard of German Aggression Page 8 Foundation of Poland's Future - Page 21 Return to the West - Page 37 No Turning Back -Page 49 First Printing, February 1947 Second Printing, July 1947 PRINED IN THE U. S. A. al, :x ..Affiliated; FOREWORD A great war has been fought and won. So tremendous and far-reaching are its consequences that the final peace settlement even now is not in sight, though the representatives of the victorious powers have been hard at work for many months. A global war requires a global peace settlement. The task is so complex, however, that a newspaper reader finds it difficult to follow the long drawn-out and wearisome negotiations over a period of many months or even of years. Moreover, some of the issues may seem so unfamiliar, so remote from the immediate interests of the average American as hardly to be worth the attention and effort their comprehension requires. -

Short History of Kashubes in the United States

A short history of Kashubs in the United States Kashubs are a Western Slavic nation, who inhabited the coastline of the Baltic Sea between the Oder and Vistula rivers.Germanization or Polonization were heavy through the 20th century, depending on whether the Kingdom of Prussia or the Republic of Poland governed the specific territory. In 1919, the Kashubian-populated German province of West Prussia passed to Polish control and became the Polish Corridor. The bulk of Kashubian immigrants arrived in the United States between 1840 and 1900, the first wave from the highlands around Konitz/Chojnice, then the Baltic coastline west of Danzig/Gdansk, and finally the forest/agricultural lands around and south of Neustadt/Wejherowo. Early Kashubs settled on the American frontier in Michigan (Parisville and Posen), Wisconsin (Portage and Trempealeau counties), and Minnesota (Winona). Fishermen settled on Jones Island along Lake Michigan in Milwaukee after the U.S. Civil War. Until the end of the 19th century, various railroad companies recruited newcomers to buy cheap farmland or populate towns in the West. This resulted in settlements in western Minnesota, South Dakota, Missouri, and central Nebraska. With the rise of industrialization in the Midwest, Kashubs and natives of Posen/Poznan took the hot and heavy foundry, factory, and steel mill jobs in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. In 1900, the number of Kashubs in the United States was estimated at around 100,000. The Kashubs did not establish a permanent immigrant identitybecause larger communities of Germans and Poles outnumbered them. Many early parishes had Kashubian priests and parishioners, but by 1900, their members were predominantly Polish. -

Hitler and the Treaty of Versailles: Wordlist

HITLER AND THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES: WORDLIST the Rhineland - a region along the Rhine River in western Germany. It includes noted vineyards and highly industrial sections north of Bonn and Cologne. demilitarized zone - in military terms, a demilitarized zone (DMZ) is an area, usually the frontier or boundary between two or more military powers (or alliances), where military activity is not permitted, usually by peace treaty, armistice, or other bilateral or multilateral agreement. Often the demilitarized zone lies upon a line of control and forms a de-facto international border. the League of Nations - the League of Nations (LON) was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference, and the precursor to the United Nations. At its greatest extent from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 members. The League's primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing war through collective security, disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration. Other goals in this and related treaties included labour conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants, trafficking in persons and drugs, arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe. the Sudetenland - Sudetenland (Czech and Slovak: Sudety, Polish: Kraj Sudetów) is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia associated with Bohemia. the Munich Agreement - the Munich Pact (Czech: Mnichovská dohoda;Slovak: Mníchovská dohoda; German: Münchner Abkommen; French: Accords de Munich; Italian:Accordi di Monaco) was an agreement permitting Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. -

German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1 The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War Edited by STEFFEN PRAUSER and ARFON REES BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2004 Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees and individual authors Published in Italy December 2004 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy www.iue.it Contents Introduction: Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees 1 Chapter 1: Piotr Pykel: The Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia 11 Chapter 2: Tomasz Kamusella: The Expulsion of the Population Categorized as ‘Germans' from the Post-1945 Poland 21 Chapter 3: Balázs Apor: The Expulsion of the German Speaking Population from Hungary 33 Chapter 4: Stanislav Sretenovic and Steffen Prauser: The “Expulsion” of the German Speaking Minority from Yugoslavia 47 Chapter 5: Markus Wien: The Germans in Romania – the Ambiguous Fate of a Minority 59 Chapter 6: Tillmann Tegeler: The Expulsion of the German Speakers from the Baltic Countries 71 Chapter 7: Luigi Cajani: School History Textbooks and Forced Population Displacements in Europe after the Second World War 81 Bibliography 91 EUI WP HEC 2004/1 Notes on the Contributors BALÁZS APOR, STEFFEN PRAUSER, PIOTR PYKEL, STANISLAV SRETENOVIC and MARKUS WIEN are researchers in the Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence. TILLMANN TEGELER is a postgraduate at Osteuropa-Institut Munich, Germany. Dr TOMASZ KAMUSELLA, is a lecturer in modern European history at Opole University, Opole, Poland. -

Public Buildings and Urban Planning in Gdańsk/Danzig from 1933–1945

kunsttexte.de/ostblick 3/2019 - 1 Ja!oda ?a5@ska-Kaczko &ublic .uildin!s and Brban &lannin! in "da#sk/$anzi! fro% 193321913 Few studies have discussed the Nazi influence on ar- formation of a Nazi-do%inated Denate that carried chitecture and urban lanning in "dańsk/Danzig.1 Nu- out orders fro% .erlin. /he Free Cit' of $anzi! was %erous &olish and "erman ublications on the city’s formall' under the 7ea!ue of Nations and unable to history, %onu%ent reservation, or *oint ublications run an inde endent forei!n olic') which was on architecture under Nazi rule offer only !eneral re- entrusted to the Fe ublic of &oland. However) its %arks on local architects and invest%ents carried out newl' elected !overn%ent had revisionist tendencies after 1933. +ajor contributions on the to ic include, a and i% le%ented a Jback ho%e to the FeichK %ono!ra h b' Katja .ernhardt on architects fro% the a!enda <0ei% ins Feich=. 4ith utter disre!ard for the /echnische 0ochschule $anzig fro% 1904–1945,2 rule of law) the new authorities banned o osition .irte &usback’s account of the restoration of historic and free ress) sought to alter the constitution) houses in the cit' fro% 1933–1939,3 a reliminary %ar!inalized the Volksta!) and curtailed the liberties stud' b' 4iesław "ruszkowski on unrealized urban of &olish and 8ewish citizens) the ulti%ate !oal bein! lanning rojects fro% the time of 4orld 4ar 66)1 their social and econo%ic exclusion. 6n so doin!) the which was later develo ed b' &iotr Lorens,3 an ex- Free Cit' of $anzi! sou!ht to beco%e one with the tensive reliminary stud' and %ono!ra h b' 8an Feich. -

Towards Modernity. the Operations of the Free City of Gdańsk's

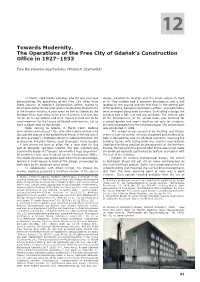

12 Towards Modernity. The Operations of the Free City of Gdańsk’s Construction Office in 1927–1933 Ewa Barylewska-Szymańska, Wojciech Szymański In March 1928 Martin Kießling, who for one year was design, keeping its location and the small square in front administering the operations of the Free City (then Freie of it.3 Two schools had a common gymnasium and a hall Stadt Danzig) of Gdańsk’s Construction Office, moved to located on the ground and the first floor in the central part Berlin to become the Director of the Construction Department of the building. Spacious classrooms, offices, and workrooms in the Finance Ministry. A year spent by him in Gdańsk by the were arranged along wide corridors. In Kießling’s design the Motława River may seem to be a short period; however, the building had a flat roof and big windows. The interior part effects of his operations and their impact turned out to be of the development, at the school back, was destined for very important for the history of Gdańsk architecture1. Let us a school garden and sports facilities not only for students, have a closer look at this period. but also for people from the neighbourhood. The construction Upon coming to Gdańsk in March 1927, Kießling was completed in 1929. immediately started to act.2 One of the first tasks undertaken by The school design prepared by Kießling and Krüger him was the change of the architectural design of the folk school refers to historic motifs, strongly simplified and modernized, for girls and boys in Pestalozzi Street in Gdańsk-Wrzeszcz.