Carbonate and Evaporite Karst Systems of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

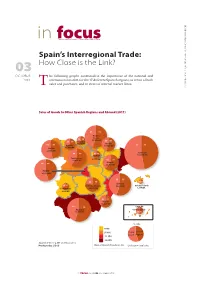

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

ROMAN ENGINEERING on the ROADS to SANTIAGO II – the Roads of the Rioja1

© Isaac Moreno Gallo http://www.traianvs.net/ _______________________________________________________________________________ ROMAN ENGINEERING ON THE ROADS TO SANTIAGO II – The roads of the Rioja1 Published in: Revista Cimbra 356 by the Colegio de Ingenieros Técnicos de Obras Públicas [College of Public Works Technical Engineers]. Isaac Moreno Gallo © 2004 [email protected] TRAIANVS © 2005 (Translated by Brian R. Bishop © 2005) Introduction The present-day area of the Rioja has since antiquity been crucial to East-West communications in the North of the Iberian Peninsula. The road that communicated with Aquitania (Aquitaine) from Asturica (Astorga) via Pompaelo (Pamplona) led off the road to Tarraco (Tarragón) through Caesaraugusta (Saragossa) by a deviation at Virovesca (Briviesca). It gave this area a special strategic importance in that it was traversed by the East-West Roman highway for the whole of its present length. Important Roman cities like Libia (Herramélluri-Leiva), Tritium Magallum (Tricio), Vareia (Varea), Calagurris (Calahorra) and Graccurris (Alfaro) flourished, doubtless with the help of this vital communication route. The whole of the later history of the Rioja is closely linked with this spinal column, which has not ceased being used up to today: it performs its purpose still in the form of a motorway. A large part of it served, as only it could, the stream of people and cultures created by the pilgrimage to St. James of Compostela. As a result of this combination of politics and history, of the means of communications, of royal interests, of religious foundations and various other factors, the pilgrim roads changed through the ages. The changes were more visible at the beginning, before the Way was established by the centres of religion and hospitality that were specially founded to attract and care for pilgrims. -

Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa

Arts 2013, 2, 6-34; doi:10.3390/arts2010006 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Review Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa Robert G. Bednarik International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), P.O. Box 216, Caulfield South, VIC 3162, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-95230549; Fax: +61-3-95230549 Received: 22 December 2012; in revised form: 22 January 2013 / Accepted: 23 January 2013 / Published: 8 February 2013 Abstract: This comprehensive review of all currently known Pleistocene rock art of Africa shows that the majority of sites are located in the continent’s south, but that the petroglyphs at some of them are of exceptionally great antiquity. Much the same applies to portable palaeoart of Africa. The current record is clearly one of paucity of evidence, in contrast to some other continents. Nevertheless, an initial synthesis is attempted, and some preliminary comparisons with the other continents are attempted. Certain parallels with the existing record of southern Asia are defined. Keywords: rock art; portable palaeoart; Pleistocene; figurine; bead; engraving; Africa 1. Introduction Although palaeoart of the Pleistocene occurs in at least five continents (Bednarik 1992a, 2003a) [38,49], most people tend to think of Europe first when the topic is mentioned. This is rather odd, considering that this form of evidence is significantly more common elsewhere, and very probably even older there. For instance there are far less than 10,000 motifs in the much-studied corpus of European rock art of the Ice Age, which are outnumbered by the number of publications about them. -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

Cantabria Y Asturias Seniors 2016·17

Cantabria y Asturias Seniors 2016·17 7 días / 6 noches Hotel Zabala 3* (Santillana del Mar) € Hotel Norte 3* (Gijón) desde 399 Salida: 11 de junio Precio por persona en habitación doble Suplemento Hab. individual: 150€ ¡TODO INCLUIDO! 13 comidas + agua/vino + excursiones + entradas + guías ¿Por qué reservar este viaje? ¿Quiere conocer Cantabria y Asturias? En nuestro circuito Reserve por sólo combinamos lo mejor de estas dos comunidades para que durante 7 días / 6 noches conozcas a fondo los mejores rincones de la geografía. 50 € Itinerario: Incluimos: DÍA 1º. BARCELONA – CANTABRIA • Asistencia por personal de Viajes Tejedor en el punto de salida. Salida desde Barcelona. Breves paradas en ruta (almuerzo en restaurante incluido). • Autocar y guía desde Barcelona y durante todo el recorrido. Llegada al hotel en Cantabria. Cena y alojamiento. • 3 noches de alojamiento en el hotel Zabala 3* de Santillana del Mar y 2 noches en el hotel Norte 3* de Gijón. DÍA 2º. VISITA DE SANTILLANA DEL MAR y COMILLAS – VISITA DE • 13 comidas con agua/vino incluido, según itinerario. SANTANDER • Almuerzos en ruta a la ida y regreso. Desayuno. Seguidamente nos dirigiremos a la localidad de Santilla del Mar. Histórica • Visitas a: Santillana del Mar, Comillas, Santander, Santoña, Picos de Europa, Potes, población de gran belleza, donde destaca la Colegiata románica del S.XII, declarada Oviedo, Villaviciosa, Lastres, Tazones, Avilés, Luarca y Cudillero. Monumento Nacional. Las calles empedradas y las casas blasonadas, configuran un paisaje • Pasaje de barco de Santander a Somo. urbano de extraordinaria belleza. Continuaremos viaje a la cercana localidad de Comillas, • Guías locales en: Santander, Oviedo y Avilés. -

CAMINOS BURGALESES: LOS CAMINOS DEL NORTE (Siglos XV Y XVI)

FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y COMUNICACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS HISTÓRICAS Y GEOGRAFÍA TESIS DOCTORAL CAMINOS BURGALESES: LOS CAMINOS DEL NORTE (Siglos XV y XVI) Salvador Domingo Mena Dirigida por Juan José García González Catedrático de Historia Medieval de la Universidad de Burgos BURGOS, 2015 A Cari, Elena Eva Juan Javier Alex y Toño. tomo I CAMINOS BURGALESES: Los Caminos del Norte (Siglos XV y XVI) Resumen l presente trabajo desarrollado como Tesis de Doctorado se enmarca dentro del pro- grama de la Universidad de Burgos que lleva por título “La vida cotidiana en Castilla Ey León” y ha sido realizado bajo la dirección del doctor D. Juan José García González, catedrático de Historia Medieval. El contenido se identifica con los itinerarios que unían la ciudad de Burgos con los puer- tos del Cantábrico centro-oriental y, en concreto, con los de Santander, Laredo, Castro- Urdiales, Bilbao y Portugalete. El autor aspira en este plano a la restitución más fidedigna posible de sus trazados y de las variantes que fueron incorporando. Su ámbito territorial comprende la mitad septentrional de la actual provincia de Bur- gos, el tramo oriental de la Comunidad Autónoma de Cantabria y el segmento occidental de las provincias de Álava y Vizcaya. El marco cronológico se circunscribe a los siglos XV y XVI o, si se prefiere, al período que opera como puente de paso de la Edad Media a la Edad Moderna. A pesar de que el territorio burgalés es y ha sido siempre una encrucijada de caminos, los estudios que se les han dedicado están bien lejos de cubrir las expectativas. -

Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Fought under the walls of Bergida Citation for published version: Brown, CJ, Torres-martínez, JF, Fernández-götz, M & Martínez-velasco, A 2018, 'Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 115-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Conflict Archaeology Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Brown, C. J., Torres-martínez, J. F., Fernández-götz, M., & Martínez-velasco, A. (2018). Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 12(2), which has been published in final form at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Anta A10– Vintage 2007 Our Perfection Denomination of Origin: D.O Ribera Del Duero

ANTA BANDERAS Anta a10– vintage 2007 Our perfection Denomination of Origin: d.o Ribera del Duero Area of Production and vineyard: Villalba de Duero (Northern Spain, Region of Castile & Leon, Province of Burgos), vineyards planted at 850-900 meters above the see level. Grape varieties: 75% Tempranillo, 5% Merlot, 20% Cabernet sauvignon Age of the vines: 10 years old Tasting notes: Balance in its countless nuances: in its fruity expression, irs aromatic chromatism. Its suggestion of spices and its soft notes of the French oak. A freestyle wine. The maximum expression of contemporariness. Food pairing: Red meats, Grilled tuna fish, strong cheese… Harvest: From the end of September till end of October. Prior to harvesting, controls of alcoholic and phenolic maturity are done in each plot and In order to preserve the quality of each grape berries and to avoid possible oxidation, we harvest at night and reception is done by gravity. Winemaking notes: Cool pré-fermentative maceration (8ºc for 48h) in order to stabilize the most expressive fruit aromas and polyphenoles. Then we leave temperature go up to 18º. During fermentation at controlled temperature of 24-25º, we proceed to “delestage” (process of fermenting red wine with skins and seeds) and “remontage” (process of pumping the fermenting grape juice over the cap during cuvaison) to the fermenting mass to insure not only a complete fermentation, but to achieve a finished wine with good fruit, soft tannins and stable color.. 13 days maceration at 27ºc. when density is as low as 60 points, devatting is done - Process -also known as “drawing”- consisting of the separation of the wine from the grape skins. -

SIG08 Davidson

CLOTTES J. (dir.) 2012. — L’art pléistocène dans le monde / Pleistocene art of the world / Arte pleistoceno en el mundo Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010 – Symposium « Signes, symboles, mythes et idéologie… » Symbolism and becoming a hunter-gatherer Iain DAVIDSON* I dedicate this paper to the memory of Andrée Rosenfeld. From the time when, as an undergraduate, I read her book with Peter Ucko (Ucko & Rosenfeld 1967) that corrected the excesses of the structuralist approach to French cave “art” to the occasion of a visit to her home only months before she passed away, I found Andrée a model of good sense about all matters to do with all forms of rock “art”. She gave me and many others nothing but sound advice and managed to navigate between theory and data with more clear sight of her destination than most others. And she was, simply, one of the nicest people who ever became an archaeologist. She will be sorely missed. Pleistocene paintings and engravings are not art From time to time, we all worry about the use of the word “art” in connection with what we study (see review in Bradley 2009, Ch. 1). The images on rock and other surfaces that concern us here have some visual similarity with some of what is called art in other contexts, particularly when they are of great beauty (e.g. Chauvet et al. 1995; Clottes 2001). Yet the associations of art –paintings, sculptures and other works– over the last six hundred years (see e.g. Gombrich 1995) (or perhaps only three hundred according to Shiner 2001), mean that it is highly unlikely that any paintings or engraved images on rocks or in caves relate to social, economic, and cultural circumstances similar in any way to those of art in the twenty-first century. -

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. the Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia Arturo de Lombera Hermida and Ramón Fábregas Valcarce (eds.) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011, 143 pp. (paperback), £29.00. ISBN-13: 97891407308609. Reviewed by JOÃO CASCALHEIRA DNAP—Núcleo de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas, 8005- 138 Faro, PORTUGAL; [email protected] ompared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Galicia investigation, stressing the important role of investigators C(NW Iberia) has always been one of the most indigent such as H. Obermaier and K. Butzer, and ending with a regions regarding Paleolithic research, contrasting pro- brief presentation of the projects that are currently taking nouncedly with the neighboring Cantabrian rim where a place, their goals, and auspiciousness. high number of very relevant Paleolithic key sequences are Chapter 2 is a contribution of Pérez Alberti that, from known and have been excavated for some time. a geomorphological perspective, presents a very broad Up- This discrepancy has been explained, over time, by the per Pleistocene paleoenvironmental evolution of Galicia. unfavorable geological conditions (e.g., highly acidic soils, The first half of the paper is constructed almost like a meth- little extension of karstic formations) of the Galician ter- odological textbook that through the definition of several ritory for the preservation of Paleolithic sites, and by the concepts and their applicability to the Galician landscape late institutionalization of the archaeological studies in supports the interpretations outlined for the regional inter- the region, resulting in an unsystematic research history. land and coastal sedimentary sequences. As a conclusion, This scenario seems, however, to have been dramatically at least three stadial phases were identified in the deposits, changed in the course of the last decade. -

Folleto Sodebur INGL 340273 .Indd

14 PROPIEDAD GARCIA Las Merindades La Bureba La DemandaPRUEBA and Pinares Amaya – Camino de Santiago The Valley of ArlanzaIMPRENTA La Ribera del Duero Burgos: a colour kaleidoscope 14 PROPIEDAD The province of Burgos, one in nine provinces making up the autonomous community of Castile and Leon, offers its visitors a territory of contrasting components: colourful landscapes and a rich legacy, whichGARCIA transports us through time. History and nature, art and culture, leisure and gastronomy come together at each corner of this beautiful and unique province. Its magical natural places, monumental buildings and picturesque rural settings are part of a visit to be made in no hurry. The province offers, moreover, culinary More information: excellence, quality wines, charm and comfortable accommodation, town and country walks and contact with its friendly people, all of which are an ideal complement to ensure and unforgettable PRUEBA getaway. Peñaladros Waterfall. Burgos is universally known for its three UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites, which include the pilgrim trail of the Camino de Santiago, the caves of the Sierra de Atapuerca and St. Mary’s Cathedral of Burgos. IMPRENTAAutor: Miguel Angel Muñoz Romero. Burgos is, however, a province which waits to be discovered. Across the length This natural landscape is inextricably bound to an important cultural heritage, a and breadth of its territory, there is a succession of small green valleys, high legacy of past settlers which is seen in the large amount of Heritage of Cultural peaks, silent paramos, gorges with vertical descents, spectacular waterfalls as Interest Goods that the province hosts around its territory. The list includes well as endless woods whose colours change from season to season.