Enhancing India-ASEAN Connectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pin-Outs (PDF)

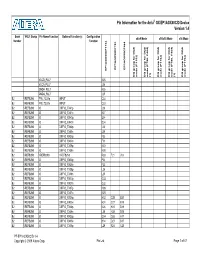

Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version 1.4 Bank VREF Group Pin Name/Function Optional Function(s) Configuration x8/x9 Mode x16/x18 Mode x36 Mode Number Function EP1AGX50DF780 EP1AGX50CF484 EP1AGX50DF1152 DQ group for DQS DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode VCCD_PLL7 K25 VCCA_PLL7 J26 GNDA_PLL7 K26 GNDA_PLL7 J25 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKp INPUT C34 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKn INPUT C33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41p J28 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41n K27 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40p E34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40n D34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40p J30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40n J29 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39p F32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39n F31 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39p K30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39n K29 B2 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 R30 T21 J18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38p F34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38n F33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38p L26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38n L25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37p G33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37n G32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37p M26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37n M25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36p H32 C28 B20 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36n H31 C27 B19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36p K28 H23 D19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36n L28 H22 D18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35p G34 D28 A17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35n H34 D27 B17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX35p L29 F24 C20 PT-EP1AGX50C/D-1.4 Copyright © 2009 Altera Corp. Pin List Page 1 of 47 Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version -

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

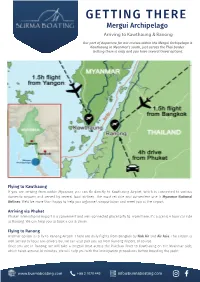

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

India: Ancient. Culture. Democracy. a Panel Discussion with Reception to Follow

FIRST-CLASS MAIL PRESORTED U.S. POSTAGE PAID SCRANTON, PA 800 Linden Street PERMIT NO. 520 Scranton, Pa 18510 The Fourth Annual Presentation in the JAY NATHAN, PH.D. VISITING SCHOLAR LECTURE SERIES India: Ancient. Culture. Democracy. A Panel Discussion with Reception to Follow Wednesday, March 29, 2017 • 5:30 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. Moskovitz Theater, The DeNaples Center The University of Scranton, Pennsylvania At the conclusion of the Panel Discussion, Kadhambari Sridhar will perform traditional dance. A reception will follow the performance. The evening is free of charge and open to the public but reservations are encouraged. Please register at scranton.edu/JayNathanLecture or call Kym Balthazar Fetsko at 570.941.7816. The Jay Nathan, Ph.D. Visiting Scholar Lecture Series The Jay Nathan, Ph.D. Visiting Scholar Lecture Series invites international scholars from the emerging democracies and the countries in political and economic transition to visit The University of Scranton to address issues that will enlighten and benefit students, faculty and community-at- large. Its purpose is to enrich the intellectual life or share a cultural exposition in the arts or music for both The University of Scranton and our Northeastern Pennsylvania community. This annual lecture initiative will highlight the research and contributions of guest scholars of international repute who will visit the University to discuss timely and timeless subjects. While visiting campus, scholars will deliver presentations on topics of interest to the academic community and meet informally with attendees, students and faculty. India: Ancient. Culture. Democracy. A Panel Discussion with Reception to Follow AMBASSADOR RIVA GANGULY DAS, DR. -

Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S

Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S. Foreign Policy October 2020 Acknowledgments Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan human rights advocacy and action organization based in Washington D.C., New York, and Los Angeles. © 2020 Human Rights First. All Rights Reserved. Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S. Foreign Policy was authored by Human Rights First’s staff and consultants. Senior Vice President for Policy Rob Berschinski served as lead author and editor-in-chief, assisted by Tolan Foreign Policy Legal Fellow Reece Pelley and intern Anna Van Niekerk. Contributing authors include: Eleanor Acer Scott Johnston Trevor Sutton Rob Berschinski David Mizner Raha Wala Cole Blum Reece Pelley Benjamin Haas Rita Siemion Significant assistance was provided by: Chris Anders Steven Feldstein Stephen Pomper Abigail Bellows Becky Gendelman Jennifer Quigley Brittany Benowitz Ryan Kaminski Scott Roehm Jim Bernfield Colleen Kelly Hina Shamsi Heather Brandon-Smith Kate Kizer Annie Shiel Christen Broecker Kennji Kizuka Mandy Smithberger Felice Gaer Dan Mahanty Sophia Swanson Bishop Garrison Kate Martin Yasmine Taeb Clark Gascoigne Jenny McAvoy Bailey Ulbricht Liza Goitein Sharon McBride Anna Van Niekerk Shannon Green Ian Moss Human Rights First challenges the United States of America to live up to its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle for human dignity and the rule of law, and so we focus our advocacy on the U.S. government and other key actors able to leverage U.S. influence. When the U.S. government falters in its commitment to promote and protect human rights, we step in to demand reform, accountability, and justice. -

A US-Indonesia Partnership for 2020: Recommendations for Forging

A U.S.–Indonesia Partnership for 2020 Recommendations for Forging a 21st Century Relationship AUTHORS A Report of the CSIS Sumitro Murray Hiebert Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Ted Osius SEPTEMBER 2013 Gregory B. Poling A U.S.- Indonesia Partnership for 2020 Recommendations for Forging a 21st Century Relationship AUTHORS Murray Hiebert Ted Osius Gregory B. Poling A Report of the CSIS Sumitro Chair for Southeast Asia Studies September 2013 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS— 50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofi t orga ni zation headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affi liated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to fi nding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. -

Violence Against Health Care in Myanmar 11 February to 12 April 2021

Violence Against Health Care in Myanmar 11 February to 12 April 2021 Around 1 p.m. on 28 March 2021 Myanmar security forces began shooting at protesters in Sanchaung township, Yangon city. As protesters fled the attack and some sought refuge in the Asia Royal Hospital, soldiers and police chased them inside, opening fire with rubber bullets and injuring at least one male hospital staff member who was exiting the hospital The security forces occupied the ground floor of the hospital and surrounded the building for approximately thirty minutes following the incident. The shooting took place near the hospital’s outpatient treatment centre for patients suffering from heart-related health issues. Mass Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) protests have been taking place across Myanmar after the Myanmar armed forces (known as the Tatmadaw) seized control of the country on 1 February following a general election that the National League for Democracy party won by a landslide. The military have since declared a state of emergency to last for at least a year, and numerous countries have condemned the takeover and subsequent violent crackdown on protesters. Hundreds of people, including children, have been killed and many injured during the protests. The violence has impacted health workers, hospitals and ambulances. On 9 April 2021 the military junta announced during a televised press conference that all health workers participating in CDM protests would be considered to be committing genocide. This document is the result of collaboration between Insecurity Insight and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights (CPHHR) as part of the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC). -

Modification of Transition-Metal Redox by Interstitial Water In

Modification of Transition-Metal Redox by Interstitial Water in Hexacyanometallate Electrodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries Jinpeng Wu†, #, Jie Song‡, Kehua Dai※, #, Zengqing Zhuo§, #, L. Andrew Wray⊥, Gao Liu#, Zhi-xun Shen†, Rong Zeng*, ‖, Yuhao Lu*, ‡, Wanli Yang*, # †Geballe Laboratory for Advanced Materials, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA #Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, United States ‡Novasis Energies, Inc., Vancouver, Washington, 98683, United States ※School of Metallurgy, Northeastern University, Shenyang 110819, China §School of Advanced Materials, Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School, Shenzhen 518055, China ⊥Department of Physics, New York University, New York, New York 10003, United States ‖Department of Electrical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China ABSTRACT A Sodium-ion battery (SIB) solution is attractive for grid-scale electrical energy storage. Low-cost hexacyanometallate is a promising electrode material for SIBs because of its easy synthesis and open framework. Most hexacyanometallate- based SIBs work with aqueous electrolyte and interstitial water in the material has been found to strongly affect the electrochemical profile, but the mechanism remains elusive. Here we provide a comparative study of the transition-metal redox in hexacyanometallate electrodes with and without interstitial water based on soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy and theoretical calculations. We found distinct transition-metal redox sequences in hydrated and anhydrated NaxMnFe(CN)6·zH2O. The Fe and Mn redox in hydrated electrodes are separated and at different potentials, leading to two voltage plateaus. On the contrary, mixed Fe and Mn redox at the same potential range is found in the anhydrated system. This work reveals for the first time that transition-metal redox in batteries could be strongly affected by interstitial molecules that are seemingly spectators. -

India – Thailand Relations: and Cultural Links in Soft Power Policy

วารสารบัณฑิตศาสน มมร. India – Thailand Relations: And Cultural Links in Soft Power Policy Phrmaha Wutthipong Rodbamrung Research Scholar Jawaharlal Nehru University India Abstract I. Introduction The article will explore the religious Thailand is part of Suvarnabhumi and cultural ties between India and Thailand territory, which finds mention even in since the ancient time. The relations in terms Ramayana by written Valmiki in c.1000 BC. of religious and cultural ties had promoted Buddhism was embraced in Thailand, while relations that contributed to the concept of the kingdom of Thailand was small state in soft power which is the popular concept in the year seven hundred in Sukkhothai international politics. It will also examine the period. Prior to that, Thailand had long ‘Look East Policy’ and ‘Look West Policy’, history in which as per the legend, Thailand and how the two Policies ‘remarriage’ in was the kingdom of Daravati, which was order to promote ‘people to people’ and the city of Mons and Thais who lived in the tourism destination under the broad domain basin site of Chao Phra ya river. U-thong of the two mechanisms: The Bay of Bengal was the ancient city, which is situated in Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Suphanburi province. Phra Pathom Cedi Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and was the big stupa which was discovered Mekong Ganga Cooperation (MCG) work to and made in third century B.C.1 (272-232 promote the role of religion and culture in B.C.). India-Thai Relations in the modern period. Accordingly, Venerable Sona and Keywords: Suvarnabhumi; Dvaravati; Venerable Uttara had been sent by King Buddhism; Brahmanism; Religious links; Asoka to Suvarnabhumi, (the land of gold) cultural links; Look East Policy, Look which was believed that gold was available in West Policy, BIMSTEC, Mekong Ganga Southeast Asia, such as Burma, Thailand, Cooperation (MCG). -

Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses

2019 Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses An Introduction of Business Opportunities and Challenges in Myanmar Prepared by Myanmar Research | Consulting | Capital Markets Contents Introduction 8 Basic Information 9 1. General Characteristics 10 1.1. Geography 10 1.2. Population, Urban Centers and Indicators 17 1.3. Key Socioeconomic Indicators 21 1.4. Historical, Political and Administrative Organization 23 1.5. Participation in International Organizations and Agreements 37 2. Economy, Currency and Finances 38 2.1. Economy 38 2.1.1. Overview 38 2.1.2. Key Economic Developments and Highlights 39 2.1.3. Key Economic Indicators 44 2.1.4. Exchange Rate 45 2.1.5. Key Legislation Developments and Reforms 49 2.2. Key Economic Sectors 51 2.2.1. Manufacturing 51 2.2.2. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 54 2.2.3. Construction and Infrastructure 59 2.2.4. Energy and Mining 65 2.2.5. Tourism 73 2.2.6. Services 76 2.2.7. Telecom 77 2.2.8. Consumer Goods 77 2.3. Currency and Finances 79 2.3.1. Exchange Rate Regime 79 2.3.2. Balance of Payments and International Reserves 80 2.3.3. Banking System 81 2.3.4. Major Reforms of the Financial and Banking System 82 Page | 2 3. Overview of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade 84 3.1. Recent Developments and General Considerations 84 3.2. Trade with Major Countries 85 3.3. Annual Comparison of Myanmar Import of Principal Commodities 86 3.4. Myanmar’s Trade Balance 88 3.5. Origin and Destination of Trade 89 3.6. -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

2.3 Nepal Road Network

2.3 Nepal Road Network Overview Primary Roads in Nepal Major Road Construction Projects Distance Matrix Road Security Weighbridges and Axle Load Limits Road Class and Surface Conditions Province 1 Province 2 Bagmati Province Gandaki Province Province 5 Karnali Province Sudurpashchim Province Overview Roads are the predominant mode of transport in Nepal. Road network of Nepal is categorized into the strategic road network (SRN), which comprises of highways and feeder roads, and the local road network (LRN), comprising of district roads and Urban roads. Nepal’s road network consists of about 64,500 km of roads. Of these, about 13,500 km belong to the SRN, the core network of national highways and feeder roads connecting district headquarters. (Picture : Nepal Road Standard 2070) The network density is low, at 14 kms per 100 km2 and 0.9 km per 1,000 people. 60% of the road network is concentrated in the lowland (Terai) areas. A Department of Roads (DoR’s) survey shows that 50% of the population of the hill areas still must walk two hours to reach an SRN road. Two of the 77 district headquarters, namely Humla, and Dolpa are yet to be connected to the SRN. Page 1 (Source: Sector Assessment [Summary]: Road Transport) Primary Roads in Nepal S. Rd. Name of Highway Length Node Feature Remarks N. Ref. (km) No. Start Point End Point 1 H01 Mahendra Highway 1027.67 Mechi Bridge, Jhapa Gadda chowki Border, East to West of Country Border Kanchanpur 2 H02 Tribhuvan Highway 159.66 Tribhuvan Statue, Sirsiya Bridge, Birgunj Connects biggest Customs to Capital Tripureshwor Border 3 H03 Arniko Highway 112.83 Maitighar Junction, KTM Friendship Bridge, Connects Chinese border to Capital Kodari Border 4 H04 Prithvi Highway 173.43 Naubise (TRP) Prithvi Chowk, Pokhara Connects Province 3 to Province 4 5 H05 Narayanghat - Mugling 36.16 Pulchowk, Naryanghat Mugling Naryanghat to Mugling Highway (PRM) 6 H06 Dhulikhel Sindhuli 198 Bhittamod border, Dhulikhel (ARM) 135.94 Km. -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT