Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Foxpro

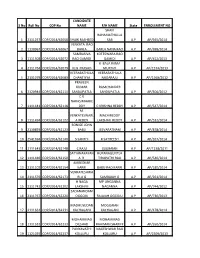

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

Electrochemical Biosensor Based on Furosemide-Gold Nanoparticles for the Determination of Dopamine for Practical Applications

ISSN: 2578-7365 Research Article Journal of Chemistry: Education Research and Practice Electrochemical Biosensor Based on Furosemide-Gold Nanoparticles for The Determination of Dopamine for Practical Applications Maqsood Ahmed Abro1, Farman Ali Mangi1, Deedar Ali Jamro1, Naimatullah Channa4, Ihsan Ali Mallah, Sikander Ali Larik1, Sajid Hussain Metlo5, Mansib Ali Jakhrani1, Dost Mohammad Kalhoro3, Aijaz Ali Otho3 & Abdul Qayoom Mugheri2* 1Department of Physics and Electronics Shah Abdul Latif University *Corresponding author Khairpur Sindh, Pakistan Abdul Qayoom Mugheri, Dr. M.A Kazi Institute of Chemistry University of Sindh Jamshoro, 76080, Sindh Pakistan 2Dr. M.A Kazi Institute of Chemistry University of Sindh Jamshoro, 76080, Sindh Pakistan Submitted: 11 Jan 2021; Accepted: 18 Jan 2021; Published: 01 Feb 2021 3Institute of plant sciences University of Sindh, Jamshoro, 76080 Sindh Pakistan 4Beijing university of Engineering of chemical technology, Beijing china 5College of nuclear science and technology Harbin engineering university of china Citation: Maqsood Ahmed Abro, Farman Ali Mangi, Deedar Ali Jamro, Naimatullah Channa, Ashan Ali Mallah, Sikander Ali Larik, Sajid Ali Metlo, Mansib Ali Jakhrani, Sajid Hussain, Dost Mohammad Kalhoro, Aijaz Ali Otho & Abdul Qayoom Mugheri (2021) Electrochemical Biosensor Based on Furosemide-Gold Nanoparticles for The Determination of Dopamine for Practical Applications. J Chem Edu Res Prac 5: 36-41. Abstract In this study, by taking the advantage of the facile & controlled synthesis of furosemide derived gold nanoparticles (Fr-AuNps) for rapid and sensitive amperometric determination of dopamine (DP). The one-step synthesis of Fr- AuNps was carried out at room temperature without the use of strong reducing agents. The synthesized Fr-AuNps were studied by UV-Vis spectroscopy, and a strong absorption band for gold nanoparticles was observed at 520 nm. -

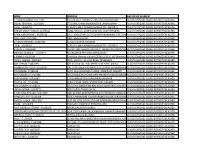

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Review Current Livestock Marketing and Its Future Prospects for the Economic Development of Balochistan–Pakistan

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY 1560–8530/2006/08–6–885–895 http://www.fspublishers.org Review Current Livestock Marketing and its Future Prospects for the Economic Development of Balochistan–Pakistan MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ1 AND MUHAMMAD AZAM KAKAR† Department of Commerce, University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan †Livestock and Dairy Development Department Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan 1Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In Pakistan, marketing of livestock and its products is dominated by the private sector. Information regarding the marketing of livestock and its products is necessary for knowing the current status and re-organizing these markets for increasing their efficiency. Secondly, it is the stated policy of the government to increase the export of agricultural products to lessen the net trade deficit. In the past, relatively more emphasis is placed on enhancing the production and productivity of livestock and its products ignoring the marketing aspects. Any lopsided production augmentation strategy could not be fruitful unless the marketing aspects are adequately addressed. Livestock marketing is the most important segment of livestock business. Hence, for ensuring reasonable returns to the producers as well as protecting consumers’ interests, an efficient marketing system is necessary. Efficient marketing systems promote production and efficient production systems attract marketing agents. In Balochistan livestock are generally marketed either at village level by personal contact between buyer and seller at special places called livestock markets organized for animal trade. These livestock markets are organized at different levels such as; sub-tehsil, tehsil and district levels on daily, weekly, fortnightly, monthly and sometimes yearly bases. These markets are traditional; therefore both buyers and sellers are mostly well informed about these market days or dates, as they are remained un-changed since ages. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Physio-Chemical Assessment of Water Sources for Drinking Purpose in Badin City, Sindh Province, Pakistan, (Water Supply Schemes and Hand Pumps)

Advance Research Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Discoveries I Vol. 29.0 I Issue – I ISSN NO : 2456-1045 Physio-Chemical assessment of water sources for drinking purpose in Badin City, Sindh Province, Pakistan, (Water Supply Schemes and Hand Pumps) Original Research Article ABSTRACT ISSN : 2456-1045 (Online) ecently, water bodies contain several types of chemicals (ICV-ENV/Impact Value): 63.78 R and the quantity is more than there were couples of years ago. (GIF) Impact Factor: 4.126 Clean and safe drinking water is one of the basic needs of life Publishing Copyright @ International Journal Foundation and society. Pakistan is the country will all types of water Journal Code: ARJMD/ENV/V-29.0/I-1/C-7/SEP-2018 resources, around the country, water quality is crossing the Category : ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE limit above WHO level standard for the drinking water of different big regions. Study area of this study is Badin city, Volume : 29.0 / Chapter-VII/ Issue-1(SEPTEMBER-2018) Sindh province, Pakistan. Present study focused on ―Physio- Journal Website: www.journalresearchijf.com Chemical assessment of water sources for drinking purpose in Paper Received: 23.09.2018 Badin City, Sindh Province, Pakistan‖. Ten sites from Badin Paper Accepted: 02.10.2018 city were decided for sampling to assess the drinking water from different water bodies, the areas names are: Canal Water Date of Publication: 10-10-2018 (Jamali Village), Hand Pump (Jamali Village), WSS Pond By Pass, Hand Pump (Laghari Village), Tap Water (Chandia Page: 38-44 Nangar), WSS Pond (Ward No-04), Filter Plant (Bilawal Park), Civil Hospital Badin, Iqra School Badin, Akram Canal etc. -

Milk Cluster Report.Pdf

CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT BASED AGRICULTURE TRANSFORMATION PLAN VISION- 2025 Milk Cluster Feasibility and Transformation Study Edited by Dr. Mubarik Ali Planning Commission of Pakistan, Ministry of Planning, Development & Special Initiatives February 2020 1 KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE 2 KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE FOREWORD In many developed and developing countries, the cluster-based development approach has become the basis for the transformation of various sectors of the economy including the agriculture sector. This approach not only improves efficiency of development efforts by enhancing stakeholders’ synergistic collaboration to resolve issues in the value chain in their local contexts, but also helps to gather resources from large number of small investors into the desirable size needed for the cluster development. I congratulate the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) and its team to undertake this study on Feasibility Analysis for Cluster Development Based Agriculture Transformation. An important aspect of the study is the estimation of resources and infrastructure required to implement various interventions along the value chain for the development of clusters of large number of agriculture commodities. The methodology used in the study can also be applied as a guide in evaluating various investment options put forward to the Planning Commission of Pakistan for various sectors, especially where regional variation is important in the project design. 3 KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE FOREWORD To improve enhance Pakistan’s competitiveness in the agriculture sector in national and international markets, the need to evaluate the value chain of agricultural commodities in the regional contexts in which these are produced, marketed, processed and traded was long felt. The Planning Commission of Pakistan was pleased to sponsor this study on the Feasibility Analysis for Cluster Development Based Agriculture Transformation to fill this gap. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Essays on the History of Sindh.Pdf

Essays On The History of Sindh Mubarak Ali Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2019) CONTENTS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Historiography of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Nasir Al-Din Qubachah (1206-1228) .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Lahribandar: A Historical Port of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 22 The Portuguese in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 Sayyid Ahmad Shahid In Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 35 Umarkot: A Historic City of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 APPENDIX .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 49 Relations of Sindh with Central Asia .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 Reinterpretation of Arab Conquest of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 79 Looters are 'great men' in History! .. .. .. .. .. .. 81 Index .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 85 INTRODUCTION The new history creates an image of the vanquished from its own angle and the defeated nation does not provide any opportunity to defend or to correct historical narrative that is not in its favour. As a result, the construction of the history made by the conquerors becomes valid without challenge. A change comes when nations fight wars of liberation and become independent after a long and arduous struggle. During this process, leaders of liberation movements are required to use history in order to fulfil their political ends. Therefore, attempts are made to glorify the past to counter the causes of their subjugation. A comprehensive plan is made to retrieve their lost past and reconstruct history to rediscover their traditions and values and strengthen their national identity. However, in some cases, subject nations are so much integrated to the culture of their conquerors that they lose their national identity and align themselves with foreign culture. They accept their version of history and recognize the aggressors as their heroes who had liberated them from their inefficient rulers and, after elimination of their out- dated traditions, introduced them to modern values and new ideas.