Lecture 124: the Bodhisattva's Dream One of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE RELIGIOUS and SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE of CHENREZIG in VAJRĀYANA BUDDHISM – a Study of Select Tibetan Thangkas

SSamaama HHaqaq National Museum Institute, of History of Art, Conservation and Museology, New Delhi THE RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF CHENREZIG IN VAJRĀYANA BUDDHISM – A Study of Select Tibetan Thangkas INTRODUCTION he tradition of thangkas has earned itself the merit of pioneering Tibetan art in the 21st century. The purpose behind the effulgent images Tis not to simply lure worshippers with their exuberant colours and designs; it also follows an intricate system of iconometric and iconologic principles in order to beseech the benefaction of a particular deity. As a result, a thangka is worshipped as a didactic ‘visual aid’ for Tibetan Buddhist reli- gious practices. Tracing the origin of the artistic and socio-cultural practices behind a thangka recreates a texture of Central Asian and Indian influences. The origin of ceremonial banners used all across Central Asia depicts a similar practice and philosophy. Yet, a close affinity can also be traced to the Indian art of paṭa painting, which was still prevalent around the eastern province of India around the Pala period.1) This present paper discusses the tradition of thangka painting as a medium for visualisation and a means to meditate upon the principal deity. The word thangka is a compound of two words – than, which is a flat surface and gka, which means a painting. Thus, a thangka represents a painting on a flat sur- 1) Tucci (1999: 271) “Pata, maṇḍala and painted representation of the lives of the saints, for the use of storytellers and of guides to holy places, are the threefold origin of Tibetan tankas”. -

The Teaching of Buddha”

THE TEACHING OF BUDDHA WHEEL OF DHARMA The Wheel of Dharma is the translation of the Sanskrit word, “Dharmacakra.” Similar to the wheel of a cart that keeps revolving, it symbolizes the Buddha’s teaching as it continues to be spread widely and endlessly. The eight spokes of the wheel represent the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the most important Way of Practice. The Noble Eightfold Path refers to right view, right thought, right speech, right behavior, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. In the olden days before statues and other images of the Buddha were made, this Wheel of Dharma served as the object of worship. At the present time, the Wheel is used internationally as the common symbol of Buddhism. Copyright © 1962, 1972, 2005 by BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI Any part of this book may be quoted without permission. We only ask that Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, Tokyo, be credited and that a copy of the publication sent to us. Thank you. BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) 3-14, Shiba 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 108-0014 Phone: (03) 3455-5851 Fax: (03) 3798-2758 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bdk.or.jp Four hundred & seventy-second Printing, 2019 Free Distribution. NOT for sale Printed Only for India and Nepal. Printed by Kosaido Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Buddha’s Wisdom is broad as the ocean and His Spirit is full of great Compassion. Buddha has no form but manifests Himself in Exquisiteness and leads us with His whole heart of Compassion. -

Skilful Means: a Concept in Mahayana Buddhism, Second Edition

SMA01C 2 11/21/03, 10:48 AM SKILFUL MEANS ‘Skilful means’ is the key principle of the great tradition of Mahayana Buddhism. First set out extensively in the Lotus Sutra, it originates in the Buddha’s compassionate project for helping others to transcend the cease- less round of birth and death. His strategies or interventions are ‘skilful means’—devices which lead into enlightenment and nirvana. Michael Pye’s clear and engaging introductory guide presents the meaning of skilful means in the formative writings, traces its antecedents in the legends of early Buddhism and explores links both with the Theravada tradition and later Japanese Buddhism. First published in 1978, the book remains the best explanation of this dynamic philosophy, which is essential for any com- plete understanding of Buddhism. Michael Pye is Professor of the Study of Religions at Marburg Univer- sity, and author of Emerging from Meditation (1990), The Buddha (1981) and the Macmillan Dictionary of Religion (1993). He is a former President of the International Association for the History of Religions (1995–2000), and has taught at the Universities of Lancaster and Leeds. SMA01C 1 11/21/03, 10:48 AM SMA01C 2 11/21/03, 10:48 AM SKILFUL MEANS A Concept in Mahayana Buddhism Second Edition MICHAEL PYE SMA01C 3 11/21/03, 10:48 AM First published in 1978 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. The Old Piano Factory, 43 Gloucester Crescent, London NW1 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” This edition published 2003 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 2003 Routledge All rights reserved. -

THE LOTUS SÚTRA Hokekyó 法華経 • One of the Earliest Mahayana Texts

THE LOTUS SÚTRA Hokekyó 法華経 • One of the earliest Mahayana texts extant, its authorship is obscure, Chinese translation from Sanskrit date from the 3 rd ct. • Usage of extremely vivid language and images, parables and analogies (to illustrate the inadequacy of verbal language to transmit the essence of Buddhist teachings)- all designed to make the Sútra accessible • Doctrinal simplicity of the text one of the most popular and influential Sutras • In one of the translations, the text alternates between prose and poetry, where the verse points to an oral transmission of the Sutra • Its text itself therefore regarded sacred- considered the embodiment of the Shakyamuni Buddha himself- copying, transcribing, painting, reading the Sútra are all activities that would bring one salvation -> the text became the most illustrated Sútra 1/ Shakyamuni was a moral being and a manifestation of the Eternal Buddha at the same time -> demonstrates his omnipresence. His appearance as Shakyamuni was only an illusion conjured for those unable to cope with receiving teaching from an apparently immortal being. ‘The Buddha therefore, upon attaining Nirvana, does not go into extinction, but abides in the world for aeons out of compassion for those still in need of teaching.’ (Keown, p. 158) 2/ ‘Just as the Buddha’s presence is extended throughout time, so the salvation of the Buddha extends to all beings’ (de Barry); i.e. all practitioners are on the path to Buddhahood SALVATION IS UNIVERSAL Including WOMEN (chapter 12- the Dragon King Daugter) important argument -

Praise for Faces of Compassion

Praise for Faces of Compassion “I appreciate Taigen Dan Leighton’s elucidation of the bodhisattvas as archetypes embodying awakened spiritual human qualities and his examples of individuals who personify these aspects. In naming, describing, and illustrating the individual bodhisattvas, his book is an informative and valuable resource.” —Jean Shinoda Bolen, M.D., author of Goddesses in Everywoman and Gods in Everyman “Vigorous and inspiring, Faces of Compassion guides the reader into the clear flavors of the awakening life within both Buddhist tradition and our broad contemporary world. This is an informative, useful, and exhilarating work of deeply grounded scholarship and insight.” —Jane Hirshfield, editor of Women in Praise of the Sacred “Such a useful book. Mr. Leighton clarifies and explains aspects of Buddhism which are often mysterious to the uninformed. The concept of the bodhisattva—one who postpones personal salvation to serve others—is the perfect antidote to today’s spiritual materialism where ‘enlightened selfishness’ has been enshrined as dogma for the greedy. This book is as useful as a fine axe.” —Peter Coyote, actor and author of Sleeping Where I Fall “In Faces of Compassion, Taigen Leighton provides us with a clear-as-a- bell introduction to Buddhist thought, as well as a short course in Far Eastern iconography and lore that I intend to use as a desk reference. What astonishes me, however, is that along the way he also manages, with surprising plausibility, to portray figures as diverse as Gertrude Stein, Bob Dylan, and Albert Einstein, among many likely and unlikely others, as equivalent Western expressions of the bodhisattva archetype. -

What Is the Lotus Sutra?” February 1, 2020

Myokei Caine-Barrett, Shonin Living the Lotus Sutra Week One: “What is the Lotus Sutra?” February 1, 2020 Hello, I am Myokei Caine-Barrett, Shonin. I'm the guiding teacher and head priest of Myoken-ji Temple in Houston, Texas, and I am also the bishop of the Nichiren Shu Order of North America. Today, I'm going to talk to you about the Lotus Sutra and the various practices associated with it. I have been practicing this form of Buddhism for about 50 years, since I was about 11 or 12 years old. I'm interested in telling you about this tradition because I think there are so many misconceptions about what we practice, why we practice, and how we do it. It is a beautiful practice. It is one that can be so enriching in your life if you are open to it. So I think that it's time to clear up some of the misconceptions about Buddhism labeled “Nichiren Buddhism,” or “Lotus Sutra Buddhism.” The Lotus Sutra, also known in Sanskrit as Saddharma Pundarika Sutra, is thought to be the highest teaching in the Nichiren school. It may not be considered so high in the rest of Buddhism. Its beginnings are India, though I believe there are very few commentaries in India about the Lotus Sutra. It traveled from India to China, where a Chinese scholar-monk, Kumarajiva, was one of the first to translate the Lotus Sutra into Chinese. He was thought to be such a gifted translator that he was imprisoned so he couldn’t translate the Lotus Sutra. -

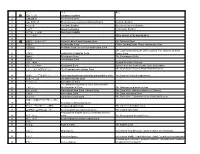

中文梵文英文1 佛釋迦牟尼佛sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛

中文 梵文 英文 1 佛 釋迦牟尼佛 Sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛 Vairocana Buddha 3 藥師璢璃光佛 Bhaiṣajya-guru-vaiḍūrya-prabhāṣa Buddha Medicine Buddha 4 阿彌陀佛 Amitābha Buddha Boundless radiance Buddha 5 不動佛 Akṣobhya Buddha Unshakable Buddha 6 然燈佛, 定光佛 Dipamkara Buddha 7 東方青龍佛 Azure Dragon of the East Buddha 8 9 經 金剛般若波羅密多經 Vajracchedika Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra The Diamond Sutra 10 華嚴經 Avataṃsaka Sutra Flower Garland Sutra; Flower Adornment Sutra 11 阿彌陀經 Amitābha Sutra; Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra The Lotus Sutra; Discourse of the Lotus of True Dharma; Dharma 12 法華經 Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sutra Flower Sutra; 13 楞嚴經 Śūraṅgama Sutra The Shurangama Sutra 14 楞伽經 Lankāvatāra Sūtra 15 四十二章經 Sutra in Forty-two Sections 16 地藏菩薩本願經 Kṣitigarbha Sutra Sutra of the Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva 17 心經 ; 般若波羅蜜多心經 The Prajnaparamita Hrdaya Sutra The Heart Sutra, Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra 18 圓覺經;大方广圆觉修多罗了义经 Mahāvaipulya pūrṇabuddhasūtra prassanārtha sūtra The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment 19 維摩詰所說經 Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa sūtra 20 三摩地王经 Samadhi-raja Sutra The Mahā prajñā pāramitā-sūtra; Śatasāhasrikā 21 大般若經 Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra; The Maha prajna paramita sutras 22 大般涅槃經 Mahā parinirvāṇa Sutra, Nirvana Sutra The Sutra of the ultimate extinction of Dharma 23 梵網經 Brahmajāla Sutra The Sutra of Brahma's Net 24 解深密經 Sandhinirmocana Sutra The Sutra of the Explanation of the Profound Secrets 勝鬘経;勝鬘師子吼一乘大方便方 25 廣經 Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra 26 佛说观无量寿佛经;十六觀經 Amitayur-dhyana Sutra The sixteen contemplate sutra 27 金光明經;金光明最勝王經 Suvarṇa-prabhāsa-uttamarāja Sutra The Golden-light Sutra -

A Guide to the Threefold Lotus Sutra by Nikkyo Niwano

A Guide to the Threefold Lotus Sutra By Nikkyo Niwano Copyright by Rissho Kosei‐kai. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents 2 PREFACE 4 PART ONE: THE SUTRA OF INNUMERABLE MEANINGS 6 Background 6 Chapter 1 Virtues 7 Chapter 2 Preaching 9 Chapter 3 Ten Merits 11 PART TWO: THE SUTRA OF THE LOTUS FLOWER OF THE WONDERFUL LAW 13 Chapter 1 Introductory 13 Chapter 2 Tactfulness 15 Chapter 3 A Parable 18 Chapter 4 Faith Discernment 22 Chapter 5 The Parable of the Herbs 25 Chapter 6 Prediction 27 Chapter 7 The Parable of the Magic City 28 Chapter 8 The Five Hundred Disciples Receive the Prediction of Their Destiny 31 Chapter 9 Prediction of the Destiny of Arhats, Training and Trained 33 Chapter 10 A Teacher of the Law 34 Chapter 11 Beholding the Previous Stupa 37 Chapter 12 Devadatta 40 Chapter 13 Exhortation to Hold Firm 43 Chapter 14 A Happy Life 45 Chapter 15 Springing Up Out of the Earth 47 Chapter 16 Revelation of the [Eternal] Life of the Tathagata 49 Chapter 17 Discrimination of Merits 52 Chapter 18 The Merits of Joyful Acceptance 55 Chapter 19 The Merits of the Preacher 56 2 Chapter 20 The Bodhisattva Never Despise 58 Chapter 21 The Divine Power of the Tathagata 59 Chapter 22 The Final Commission 62 Chapter 23 The Story of the Bodhisattva Medicine King 63 Chapter 24 The Bodhisattva Wonder Sound 64 Chapter 25 The All‐Sidedness of the Bodhisattva Regarder of the Cries of the 66 World Chapter 26 Dharanis 67 Chapter 27 The Story of the King Resplendent 68 Chapter 28 Encouragement of the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue 70 PART THREE: THE SUTRA OF MEDITATION ON THE BODHISATTVA UNIVERSAL VIRTUE 71 The Sutra of Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue 71 3 Preface In recent years, as the crises facing humankind have become more numerous and more acute, interest in the Lotus Sutra has begun to increase. -

July-September 2010, Volume 37(PDF)

July-Sept. 2010 Vol. 37 DHARMA WORLD for Living Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue CONTENTS Tackling the Question "What Is the Lotus Sutra?" The International Lotus Sutra Seminar by Gene Reeves 2 Cover image: Abinitio Design. Groping Through the Maze of the Lotus Sutra by Miriam Levering 5 The International Lotus Sutra Seminar 2 A Phenomenological Answer to the Question "What Is the Lotus Sutra?" by Donald W. Mitchell 9 DHARMA WORLD presents Buddhism as The Materiality of the Lotus Sutra: Scripture, Relic, a practical living religion and promotes and Buried Treasure by D. Max Moerman 15 interreligious dialogue for world peace. It espouses views that emphasize the dignity oflife, seeks to rediscover our inner nature The Lotus Sutra Eludes Easy Definition: A Report and bring our lives more in accord with it, on the Fourteenth International Lotus Sutra Seminar and investigates causes of human suffering. by Joseph M. Logan 23 It tries to show how religious principles help solve problems in daily life and how Groping Through the Maze of the least application of such principles has the Lotus Sutra 5 wholesome effects on the world around us. Reflections It seeks to demonstrate truths that are fun Like the Lotus Blossom by Nichiko Niwano 31 damental to all religions, truths on which all people can act. The Buddha's Teachings Affect All of Humankind by Nikkyo Niwano 47 Niwano Peace Prize Women, Work, and Peace by Ela Ramesh Bhatt 32 Publisher: Moriyasu Okabe The Materiality of Executive Director: Jun'ichi Nakazawa the Lotus Sutra 15 Director: Kazumasa Murase Interview Editor: Kazumasa Osaka True to Self and Open to Others Editorial Advisors: An interview with Rev. -

April 2021 Living Buddhism, Pp. 53–62 “The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life”

SGI-USA Study Department April 2021 Study Support Material April 202 Living Buddhism, pp. 53–62 “THE BUDDHISM OF THE SUN: ILLUMINATING THE WORLD” [63] TO OUR FUTURE DIVISION MEMBERS, THE1 TORCHBEARERS OF JUSTICE—OUR HOPE FOR THE FUTURE PART 2 “The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life”—Humanity Is Awaiting Your Growth POINTS TO KEEP IN MIND REGARDING BUDDHIST STUDY IN THE SGI 1) Our understanding of Nichiren Buddhism has deepened significantly since the 1991 priesthood issue— culminating in doctrinal clarifications in 2014. What Nichiren Shoshu teaches is completely different from the teachings of Nichiren Daishonin, the foundation of SGI study. 2) SGI is a “living” religion with a “living” philosophy, meaning that the application of the core, unchanging principles of Buddhism is always adapting to changing times and circumstances. 3) Even for longtime members, it is important to continue studying current materials. Our mentor’s explanations of Nichiren’s writings in his monthly lectures represent this “living” Buddhism. GOALS FOR PRESENTERS 1) Let’s learn together: This is the recommended approach for presenting Ikeda Sensei’s lectures. Rather than lecturing on his lectures, the goal of the monthly presentations is to study the material together with fellow members. With this in mind, presenters should aim to read the material several times and share 2 or 3 key points that inspire them, rather than attempting to cover every point. 2) Let’s unite with the heart of our mentor: Sensei strives to encourage members through his lectures, just as Nichiren did through his writings. Let’s strive to convey this spirit as we study with fellow members and apply these teachings in our daily lives, efforts in society and advancement of kosen-rufu. -

Read Book the Lotus Sutra

THE LOTUS SUTRA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Burton Watson | 390 pages | 07 Apr 1994 | Columbia University Press | 9780231081610 | English | New York, United States The Lotus Sutra PDF Book Maitreya is puzzled by this because he knows that the Buddha only achieved enlightenment forty years ago. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. As will be discussed in the next chapter, scholars speculate that this was the final chapter of an earlier version of the Lotus , with the last six chapters being interpolations. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. JS: Right. The Lotus Sutra was found in Gilgit region, now in Pakistan. It also symbolizes the purity of Buddhahood, blooming in the midst of our ordinary lives just as the lotus blossoms in muddy pond water. Follow our work:. I think, for example, about Japan in the early 20th century when Buddhist leaders there had their first encounters with European Buddhist Studies. There is no point in carrying the raft once the journey has been completed and its function fulfilled. DL: There were many in India who rejected the claim that the Mahayana sutras were the word of the Buddha. These bodhisattvas choose to remain in the world to save all beings and to keep the teaching alive. Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube. Print Cite. Nichiren Buddhism Tiantai Buddhism J. Learn More in these related Britannica articles:. Journal of Chinese Philosophy. He emits a ray of light from between his eyes, illuminating all the realms to the east, from the highest heavens to the lowest hells. Donald S. And Shariputra says: No, because he wanted to save the lives of his beloved children. -

Conceptions of the Absolute in Mahayana Buddhism and the Pure Land Way by John Paraskevopoulos

Conceptions of the Absolute in Mahayana Buddhism and the Pure Land Way by John Paraskevopoulos A perennial problem for Buddhists has always been the question of how to articulate the relationship that obtains between the Absolute and the Relative orders of reality, ie. between Nirvana and Samsara. Although conceptions of Nirvana within the Buddhist tradition have changed over the centuries, it is safe to say that some of its features have remained constant throughout the doctrinal permutations of its different schools. Indeed, some modern scholars of Buddhism in the West have even ques- tioned whether it is meaningful to speak of an Absolute in Buddhism at all claiming that such a notion is an illegitimate transposition of certain ‘substantialist’ notions relating to the highest reality as found in its par- ent tradition, Hinduism. This paper will attempt to address the question of whether one can meaningfully speak of an Absolute in Buddhism, in what such a reality consists and what its implications are for understand- ing the highest goal of the Buddhist path. In doing so, this paper will be focussing chiefly on the Mahayana tradition and, in particular, on one of its principal metaphysical texts—The Awakening of Faith—in which we arguably find one of the most comprehensive treatments of the Ultimate Reality in the history of Buddhism. The paper will then address some of the implications of this discussion for understanding the Pure Land way— a spiritual path pre-eminently suited to the exigencies of the Decadent Age of the Dharma (Jp: mappo¯) in which we currently find ourselves.