Bridging the Gap Between Community Ecology and Historical Biogeography: Niche Conservatism and Community Structure in Emydid Turtles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biogeography, Community Structure and Biological Habitat Types of Subtidal Reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand

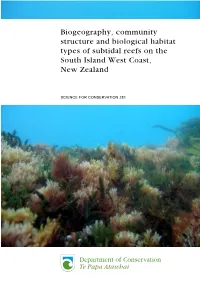

Biogeography, community structure and biological habitat types of subtidal reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 281 Biogeography, community structure and biological habitat types of subtidal reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand Nick T. Shears SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 281 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Cover: Shallow mixed turfing algal assemblage near Moeraki River, South Westland (2 m depth). Dominant species include Plocamium spp. (yellow-red), Echinothamnium sp. (dark brown), Lophurella hookeriana (green), and Glossophora kunthii (top right). Photo: N.T. Shears Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright December 2007, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 (hardcopy) ISSN 1177–9241 (web PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–14354–6 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14355–3 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. -

Genetic Methods for Estimating the Effective Size of Cetacean Populations

Genetic Methods for Estimating the Effective Size of Cetacean Populations Robin S. Waples Northwest Fisheries Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, 2725 Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, Washington 98112, USA ABSTRACT Some indirect (genetic) methods for estimating effective population size (N,) are evaluated for their suitability in studyingcetacean populations. The methodscan be grouped into those that (1) estimate current N,, (2) estimate long-term N, and (3) provide information about recent genetic bottlenecks. The methods that estimate current effective size are best suited for the analysis of small populations. and nonrandom sampling and population subdivision are probably the most serious sources of potential bias. Methods that estimate long-term N, are best suited to the analysis of large populations or entire species, may be more strongly influenced by natural selection and depend on accurate estimates of mutation or DNA base substitution rates. Precision of the estimates of N, is likely to be a limiting factor in many applications of the indirect methods. Keywords: genetics; assessment: cetaceans - general: evolution. INTRODUCTION Population size is one of the most important factors that determine the rate of various evolutionary processes, and it appears as a parameter in many of the fundamental equations of population genetics. However, knowledge merely of the total number of individuals (N) in a population is not sufficient for an accurate description of these evolutionary processes. Because of the influence of demographic parameters, two populations of the same total size may experience very different rates of genetic change. Wright (1931; 1938) developed the concept of effective population size (N,) as a way of summarising relevant demographic information so that one can predict the evolutionary consequences of finite population size (see Fig. -

Ecological Principles and Function of Natural Ecosystems by Professor Michel RICARD

Intensive Programme on Education for sustainable development in Protected Areas Amfissa, Greece, July 2014 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ecological principles and function of natural ecosystems By Professor Michel RICARD Summary 1. Hierarchy of living world 2. What is Ecology 3. The Biosphere - Lithosphere - Hydrosphere - Atmosphere 4. What is an ecosystem - Ecozone - Biome - Ecosystem - Ecological community - Habitat/biotope - Ecotone - Niche 5. Biological classification 6. Ecosystem processes - Radiation: heat, temperature and light - Primary production - Secondary production - Food web and trophic levels - Trophic cascade and ecology flow 7. Population ecology and population dynamics 8. Disturbance and resilience - Human impacts on resilience 9. Nutrient cycle, decomposition and mineralization - Nutrient cycle - Decomposition 10. Ecological amplitude 11. Ecology, environmental influences, biological interactions 12. Biodiversity 13. Environmental degradation - Water resources degradation - Climate change - Nutrient pollution - Eutrophication - Other examples of environmental degradation M. Ricard: Summer courses, Amfissa July 2014 1 1. Hierarchy of living world The larger objective of ecology is to understand the nature of environmental influences on individual organisms, populations, communities and ultimately at the level of the biosphere. If ecologists can achieve an understanding of these relationships, they will be well placed to contribute to the development of systems by which humans -

Community Ecology

Schueller 509: Lecture 12 Community ecology 1. The birds of Guam – e.g. of community interactions 2. What is a community? 3. What can we measure about whole communities? An ecology mystery story If birds on Guam are declining due to… • hunting, then bird populations will be larger on military land where hunting is strictly prohibited. • habitat loss, then the amount of land cleared should be negatively correlated with bird numbers. • competition with introduced black drongo birds, then….prediction? • ……. come up with a different hypothesis and matching prediction! $3 million/yr Why not profitable hunting instead? (Worked for the passenger pigeon: “It was the demographic nightmare of overkill and impaired reproduction. If you’re killing a species far faster than they can reproduce, the end is a mathematical certainty.” http://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june- 2014/why-passenger-pigeon-went-extinct) Community-wide effects of loss of birds Schueller 509: Lecture 12 Community ecology 1. The birds of Guam – e.g. of community interactions 2. What is a community? 3. What can we measure about whole communities? What is an ecological community? Community Ecology • Collection of populations of different species that occupy a given area. What is a community? e.g. Microbial community of one human “YOUR SKIN HARBORS whole swarming civilizations. Your lips are a zoo teeming with well- fed creatures. In your mouth lives a microbiome so dense —that if you decided to name one organism every second (You’re Barbara, You’re Bob, You’re Brenda), you’d likely need fifty lifetimes to name them all. -

Can More K-Selected Species Be Better Invaders?

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2007) 13, 535–543 Blackwell Publishing Ltd BIODIVERSITY Can more K-selected species be better RESEARCH invaders? A case study of fruit flies in La Réunion Pierre-François Duyck1*, Patrice David2 and Serge Quilici1 1UMR 53 Ӷ Peuplements Végétaux et ABSTRACT Bio-agresseurs en Milieu Tropical ӷ CIRAD Invasive species are often said to be r-selected. However, invaders must sometimes Pôle de Protection des Plantes (3P), 7 chemin de l’IRAT, 97410 St Pierre, La Réunion, France, compete with related resident species. In this case invaders should present combina- 2UMR 5175, CNRS Centre d’Ecologie tions of life-history traits that give them higher competitive ability than residents, Fonctionnelle et Evolutive (CEFE), 1919 route de even at the expense of lower colonization ability. We test this prediction by compar- Mende, 34293 Montpellier Cedex, France ing life-history traits among four fruit fly species, one endemic and three successive invaders, in La Réunion Island. Recent invaders tend to produce fewer, but larger, juveniles, delay the onset but increase the duration of reproduction, survive longer, and senesce more slowly than earlier ones. These traits are associated with higher ranks in a competitive hierarchy established in a previous study. However, the endemic species, now nearly extinct in the island, is inferior to the other three with respect to both competition and colonization traits, violating the trade-off assumption. Our results overall suggest that the key traits for invasion in this system were those that *Correspondence: Pierre-François Duyck, favoured competition rather than colonization. CIRAD 3P, 7, chemin de l’IRAT, 97410, Keywords St Pierre, La Réunion Island, France. -

National Wildlife Federation's Community Wildlife Habitat

National Wildlife Federation’s Community Wildlife Habitat Certification Requirements To achieve certification through the National Wildlife Federation’s Community Wildlife Habitat program, you must create or restore wildlife habitat in your community and do education and outreach. First, a certain number of homes, schools and common areas must become National Wildlife Federation Certified Wildlife Habitats by providing the four basic elements that all wildlife need: food, water, cover and places to raise young. The NWF Certified Wildlife Habitat program also requires sustainable gardening practices such as using rain barrels, reducing water usage, removing invasive plants, using native plants and eliminating pesticides. These requirements are based on population – see chart below. Second, communities earn education and outreach points through a flexible checklist that includes educating citizens at community events, hosting a native plant sale, organizing a stream clean up, bringing new partners to the effort and hosting workshops – see pages 2 and 3. Property Certification Requirements: Minimum Habitat Sliding Scale Based on Activity / Type of Certification Points Certification Points Population Size For each home certified, including townhomes and apartments 1 20 500 or Less For each common area certified, including public parks, HOA common 40 501-1,000 areas, businesses, places of worship, farms, universities and municipal 3 100 1,001-5000 buildings 150 5,001-10,000 For each school certified as an NWF Schoolyard Habitat - Pre-K - 12 or 175 10,001-15,000 5 nature center 200 15,001-20,000 225 20,001-25,000 250 25,001-50,000 VERIFICATION: Each home or common area must be certified within 15 300 50,001-100,000 years of a community's registration date to count for points. -

Integrating Community and Ecosystem-Based Approaches in Climate

Integrating Community and Ecosystem-Based Approaches in Climate Change Adaptation i Responses This paper is the result of extensive discussions led by adaptation professionals coming from different backgrounds and facilitated by the Ecosystem and Livelihoods Adaptation Network (ELAN).ii ELAN is an innovative alliance between two conservation organisations (International Union for the Conservation of Nature [IUCN] and WWF) and two development organisations (CARE International and the International Institute for Environment and Development [IIED]). The objective of ELAN is to establish a global network to develop, evaluate, synthesize and share successful strategies for adapting to climate change, build capacity for such strategies to be assessed and implemented at national and sub-national levels, and advance policies and knowledge sharing platforms that will facilitate the scaling up of effective strategies. Two emerging approaches to adaptation have gained currency over the past few years, namely Community-based Adaptation (CBA) and Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EBA). Each has its specific emphasis, the first on empowering local communities to reduce their vulnerabilities, and the latter on harnessing the management of ecosystems as a means to provide goods and services in the face of climate change. In this paper, ELAN argues for a more truly “integrated approach” to adaptation that addresses and seeks to reconcile differences between CBA and EBA. ELAN has developed a conceptual framework for an approach to adaptation, which empowers -

Effective Size of Populations with Heritable Variation in Fitness

Heredity (2002) 89, 413–416 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy SHORT REVIEW Effective size of populations with heritable variation in fitness T Nomura Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Engineering, Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto 603–8555, Japan The effective size of monogamous populations with heritable zygotes are produced by random union of gametes, each variation in fitness is formulated, and the expression from conceptual male and female gametic pools. A con- obtained is compared with a published equation. It is shown venient equation for practical use is proposed, and the appli- that the published equation for dioecious populations is inap- cation is illustrated with the estimation of the effective size propriate for most animal and human populations, because of a rural human community in Japan. the derivation is implicitly based on the assumption that Heredity (2002) 89, 413–416. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800169 Keywords: effective population size; random genetic drift; fitness; heritability; human population; animal population Introduction situations have been developed (Santiago and Caballero, 1995; Nomura, 1996, 1997; Wang, 1998; Bijma et al, 2000, The effective size of a population is a parameter central 2001). Only one extension to directional selection on fit- to understanding evolution in small populations, because ness was given by Nei and Murata (1966). Based on the the magnitude of this parameter determines the genetic approach of Robertson (1961), they worked out an equ- effects of both inbreeding and genetic drift (Falconer, ation for monoecious populations. They also extended 1989; Caballero, 1994). This parameter is also important their derivation to dioecious populations. -

A Guide to Community-Based Habitat Restoration

Why Restore? HABITAT DESTRUCTION AND DEGRADATION are among our most seri- ous environmental crises, causing species extinctions and threatening many remaining wildlife populations around the world. In California, f population growth and associated coastal development have caused In California, population the loss of over 90 percent of our wetlands. Although the passage of growth and associated environmental laws in the 1970s, including the California Coastal Act, coastal development have has helped to slow this decline, many remaining wetlands continue to caused the loss of over 90 be threatened by development and are degraded by poor water qual- percent of our wetlands. ity, invasive species, and other threats. In addition to making sure that f no more loss occurs, an important new challenge is to restore wetlands and other critical habitat wherever feasible. This guide describes how citizens can become involved in helping to improve and restore coastal wetlands and other coastal habitat in their communities. he california coastal commission’s community-Based t restoration and education program In 1972, the citizens of California passed Proposition 20, known as the “Save the Coast” initiative, which called for the formation of a statewide planning and regulatory agency named the California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission. Made permanent by the 1976 Coastal Act, and now known as the California Coastal Commission, the Commission has spent the past 30 years working to preserve and protect the resources of our 1,100 miles of coastline. The Commission’s Public Education Pro- gram complements the work of its regulatory and planning programs by empowering the public to become stewards of our coast and ocean and take environmentally positive action. -

And K-Selection History

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.04.455033; this version posted August 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Robust bacterial co-occurence community structures are independent of r- and K-selection history Jakob Peder Pettersen1, Madeleine S. Gundersen1, and Eivind Almaas1,2,* 1Department of Biotechnology and Food Science, NTNU- Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 2K.G. Jebsen Center for Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Public Health and General Practice, NTNU - Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Selection for bacteria which are K-strategists instead of r-strategists has been shown to improve fish health and survival in aquaculture. We considered an experiment where microcosms were inoculated with natural seawater and the selection regime was switched from K-selection (by continuous feeding) to r-selection (by pulse feeding) and vice versa. We found the networks of significant co-occurrences to contain clusters of taxonomically related bacteria having positive associations. Comparing this with the time dynamics, we found that the clusters most likely were results of similar niche preferences of the involved bacteria. In particular, the distinction between r- or K-strategists was evident. Each selection regime seemed to give rise to a specific pattern, to which the community converges regardless of its prehistory. Furthermore, the results proved robust to parameter choices in the analysis, such as the filtering threshold, level of random noise, replacing absolute abundances with relative abundances, and the choice of similarity measure. -

Conservation Genetics the Institute’S Researchers Develop Methods and Tools in Conservation Genetics, and Apply These to Inform the Conservation of Threatened Species

Main image: bumblebee family lineage survival historical and current effective population size For further information, contact Jinliang Wang: is enhanced in high-quality landscapes. Inset left: of Hainan gibbons [email protected] IMPACT AREAS microsatellite data are used to investigate the Conservation genetics The Institute’s researchers develop methods and tools in conservation genetics, and apply these to inform the conservation of threatened species. enetic diversity influences the these methods to investigate the historical health and long-term survival of and current effective population size of populations, with decreased genetic Hainan gibbons (Nomascus hainanus) from Gdiversity associated with reduced fitness microsatellite data (Bryant et al. 2016). and adaptability to changing environments. Conservation genetics provides the theory Inferring population structure and methods to estimate historical and Individuals of a species may not constitute current genetic diversity and to predict a genetically homogeneous population. the future distribution of genetic diversity Instead, they are usually clustered into in populations and species. This crucial different populations due to patchy information informs conservation strategy geographic distribution and a limited ability in order to minimise risk of extinction in to disperse. Inferring population structure by threatened species. delineating the number and distribution of populations and by measuring the genetic Estimating effective differentiation among populations helps population size us to understand the current distribution Threatened species usually have small and of genetic diversity. declining population sizes, and genetic Institute research has shown that the diversity is lost due to genetic stochasticity. most appropriate statistic for quantifying The rate of loss of genetic diversity is genetic differentiation is Fst (a measure determined by the effective population of genetic differentiation between size (Ne) of the species, which is affected by populations). -

Ecology the Study of the Relationships Between Living Organisms and Their Environment Biosphere: Levels of Organization

Ecology The study of the relationships between living organisms and their environment Biosphere: Levels of Organization The organization of the biosphere from the most specific to the broadest level: Organism Population Community Ecosystem Biome Biosphere Biosphere = any part of the Earth where organisms live, broadest level of ecological study, includes all of Earth’s ecosystems The biosphere includes the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere Biosphere Biome Biome = a geographic region that has separate but similar ecosystems characterized by a distinct climate Climate of a location determines which types of organisms are able to live there The major biomes on Earth include: tropical rainforest, temperate rainforest, desert, grassland, deciduous forest, coniferous forest, tundra, estuary, savanna, and taiga. Ecosystem Ecosystem = the biotic, or living, community and its abiotic, or nonliving, environment Ecosystems vary greatly in size and conditions The plants and animals of an ecosystem are determined by the abiotic factors Example of an Ecosystem All the living and nonliving factors inside a pond: The water in the pond The algae and plants that grow in the water The animals and bacteria that live in the water The dirt and rocks on the bottom The sunlight on the water Biotic vs. Abiotic Factors Biotic Factors: Living organisms and factors from formerly living organisms Include interactions between members of the same species and different species Abiotic Factors: Any nonliving geological, geographical and climatological